The “European New Right”: Defining and Defending Europe’s Heritage

An Interview with Alain de Benoist

Charting Europe’s Future in the ‘Post Postwar’ Era

In the following essay and interview, Professor Warren takes a close look at the “European New Right,” a cultural-intellectual movement that offers not only an unconventional view of the past, but a challenging perspective on the present and future. This piece admittedly represents a departure from the Journal’s usual content and tone. All the same, we hope and trust that readers will appreciate this look at an influential movement that not only revives an often neglected European intellectual-cultural tradition, but which also – as French writer Alain de Benoist explains here – seeks to chart Europe’s course into the 21st century.– The Editor

Ian Warren is the pen name of a professor who teaches at a university in the midwest. This interview/ article is the second of a series.

During the postwar era – approximately 1945–1990 – European intellectual life was dominated by Marxists (most of them admirers of the Soviet experiment), and by supporters of a liberal-democratic society modeled largely on the United States. Aside from important differences, each group shared common notions about the desirability and ultimate inevitability of a universal “one world” democratic order, into which individual cultures and nations would eventually be absorbed.

Not all European thinkers accepted this vision, though. Since the late 1960s, a relatively small but intense circle of youthful scholars, intellectuals, political theorists, activists, professors, and even a few elected parliamentarians, has been striving – quietly, but with steadily growing influence – to chart a future for Europe that rejects the universalism and egalitarianism of both the Soviet Marxist and American capitalist models.

This intellectual movement is known – not entirely accurately – as the European New Right, or Nouvelle Droite. (It should not be confused with any similarly named intellectual or political movement in Britain or the United States, such as American “neo-conservatism.”) European New Right voices find expression in numerous books, articles, conferences and in the pages of such journals as Eléments, Scorpion and Transgressioni.

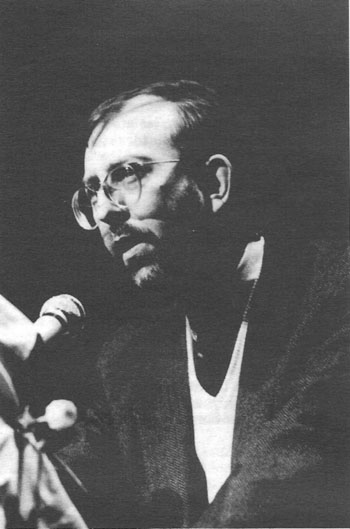

No one has played a more important role in this movement than Alain de Benoist, a prolific French writer born in 1943. As the chief philosopher of the Nouvelle Droite, he serves as a kind of contemporary Diogenes in European intellectual life. According to the critical Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right, de Benoist is “an excellent stylist, cultivated and highly intelligent.”[1]

He has explained his worldview in a prodigious outpouring of essays and reviews, and in several books, including a brilliant 1977 work, Vu de Droite (“Seen from the Right”), which was awarded the coveted Grand Prix de l’Essai of the Académie Française. (His books have been translated into Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, German, Dutch and Arabic, but none has yet appeared in English.)

For some years a regular contributor to the French weekly Le Figaro Magazine, de Benoist has served as editor of the quarterly Nouvelle Ecole, of the magazine Eléments, and, most recently, of a quarterly review, Krisis.[2] For some years he also played a leading role in the operation of the Paris-based group GRECE (“Research and Study Group for European Civilization”), which is sometimes described as an organizational expression of the Nouvelle Droite.[3]

De Benoist’s fondest wish, he once said, would be to see the “peoples and cultures of the world again find their personality and identity.” He believes that Europe has largely sold its soul for a mess of cheap “Made in the USA” pottage. American-style economic and cultural hegemony is a “soft” but insidious totalitarianism that erodes the character of individuals and the heritage of nations. To the peoples of Europe, de Benoist and the European New Right insistently pose this question: How can we preserve and sustain our diversity in the face a consumer-driven world based largely on a synthetic universalism and egalitarianism?

A dramatic indication of de Benoist’s importance came during a visit to Berlin in February 1993, when he was attacked and beaten by about 20 young “anti-fascist” thugs.

Few people on this side of the Atlantic know much about de Benoist and the intellectual movement he represents. The most cogent and useful overview in English is a 200-page book, Against Democracy and Equality: The European New Right, by Tomislav Sunic, a Croatian-born American political scientist.[4]

The task of the European New Right, explains professor Sunic in his 1990 monograph, is to defend Europe – especially its rich cultural heritage – above all from the economic-cultural threat from the United States.[5] According to Sunic:[6]

The originality of the [European] New Right lies precisely in recognizing the ethnic and historical dimensions of conservatism – a dimension considered negligible by the rather universalist and transnational credo of modern Western conservatives …

The New Right characterizes itself as a revolt against formless politics, formless life, and formless values. The crisis of modern societies has resulted in incessant “uglification” whose main vectors are liberalism, Marxism and the “American way of life.” Modern dominant ideologies, Marxism and liberalism, embedded in the Soviet Union and America respectively, are harmful to the social well-being of the peoples, because both reduce every aspect of life to the realm of economic utility and efficiency.

The principle enemy of freedom, asserts the New Right, is not Marxism or liberalism per se, but rather common beliefs in egalitarianism.

In the intellectual climate of the postwar era, writes Sunic, “those who still cherished conservative ideas felt obliged to readapt themselves to new intellectual circumstances for fear of being ostracized as ‘fellow travellers of fascism’.”[7] The European New Right draws heavily from and builds upon the prewar intellectual tradition of such anti-liberal figures as the Italians Vilfredo Pareto and Roberto Michels, and the Germans Oswald Spengler and Carl Schmitt. Not surprisingly, then, Nouvelle Droite thinkers are sometimes dismissively castigated as “fascist.”[8]

In the view of the European New Right, explains Sunic, “The continuing massification and anomie in modern liberal societies” is a symptom “of the modern refusal to acknowledge man’s innate genetic, historical and national differences as well as his cultural and national particularities – the features that are increasingly being supplanted with a belief that human differences occur only as a result of different cultural environments.”[9]

Real, “organic” democracy can only thrive, contends de Benoist, in a society in which people share a firm sense of historical and spiritual commitment to their community. In such an “organic” polity, the law derives less from abstract and preconceived principles, than from shared values and civil participation.[10] “A people,” argues Benoist, “is not a transitory sum of individuals. It is not a chance aggregate,” but is, instead, the “reunion of inheritors of a specific fraction of human history, who on the basis of the sense of common adherence, develop the will to pursue their own history and given themselves a common destiny.”[11]

New Right thinkers warn of what they regard as the dangers inherent in multi-racial and multi-cultural societies. In their view, explains Sunic,[12]

A large nation coexisting with a small ethnic group within the same body politic, will gradually come to fear that its own historical and national identity will be obliterated by a foreign and alien body unable or unwilling to share the same national, racial, and historical consciousness.

Sharply rejecting the dogma of human equality that currently prevails in liberal democratic societies, these New Right thinkers cite the work of scientists such as Hans Eysenck and Konrad Lorenz.[13] At the same time, the European New Right rejects all determinisms, whether historical, economic or biological. Contends de Benoist: “In the capacity of human being, for man, culture has primacy over nature, history has primacy over biology. Man becomes by creating from what he already is. He is the creator himself.”[14]

Consistent with its categorical rejection of universalism, the European New Right rejects the social ideology of Christianity. In de Benoist’s view, the Christian impact on Europe has been catastrophic. Christian universalism, he contends, was the “Bolshevism” of antiquity.[15]

In spite of the formidable resistance of an entrenched liberal-Marxist ideology, the impact of the European New Right has been considerable. While its views have so far failed to win mass following, it has had considerable success in eroding the once almost total leftist-liberal intellectual hegemony in Europe, and in restoring a measure of credibility and respect to Europe’s prewar conservative intellectual heritage. In Sunic’s opinion, the merit of the European New Right has been to warn us that “totalitarianism need not necessarily appear under the sign of the swastika or the hammer and sickle,” and to “draw our attention” to the defects of contemporary liberal (and communist) societies.[16]

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the collapse of the Iron Curtain (perhaps most dramatically symbolized by the tearing down of the Berlin wall), the end of USA-USSR Cold War rivalry, as well as mounting political, economic and ethnic problems in Europe, a new age has dawned across the continent – an era not only of new problems and danger, but also of new opportunities. In this new age, the struggle of the European New Right takes on enormously greater relevance and importance.

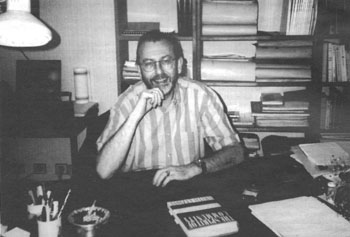

One evening in June 1993, this writer had the opportunity to meet at length with Alain de Benoist in his Paris office. Amid a prodigious clutter of accumulated books, journals, and pamphlets, this prolific philosopher and influential intellectual “agitator” provided insights and observations in reply to a series of questions. (Our meeting had been arranged by Professor Sunic, who sat in on the discussion.)

Q: Let me first ask you how it happened that you became, in effect, the founder of a new intellectual movement. Exactly how did this come about?

B: I did not set out to do this. In 1968, when I was 25 years old, I had the idea of creating a new journal – a more or less academic or, better yet, a theoretical journal, which was given the name Nouvelle Ecole [“New School”]. At first it was not even printed, merely photocopied in a very primitive way. Still, it achieved a certain success, and after a while some friends wanted to try to organize the readership into a cultural association. So that was the beginning. This association later took the name of GRECE. I was not involved in actually founding GRECE, because I am not so much a man of organizations or movements, even cultural. I’m more what you might call a “closet intellectual.” Since that beginning more than 25 years ago, there have been many conferences, colloquia, books, booklets, papers, and journals. This movement has never been directly connected with politics; rather it has been cultural, philosophical, and theoretical. Of course, we are interested in politics, but, like all those who see themselves as intellectuals, only as spectators.

Q: What do see as the future of the movement? Do you see any particular end in view?

B: No, I have no intention of changing myself or to change what I do. But your question is, what is the destiny of ideas. Oh, sometimes it’s nothing at all, but you never know. It’s impossible to know. What you can say is that in world history, especially in the recent world history, in my opinion, there can be no political revolution, or even a major political event, if there had not already occurred some kind of change in the minds of the people. So I believe that the cultural revolution comes first, and the political revolution comes after that. But that does not mean that when you make something cultural, it is because you want, in the end, to make something political. This is not done by the same people, you see. If I can give an example, the French Revolution probably would not have been possible without the work of the Enlightenment philosophers. Yet, it was not these philosophers who actually made the revolution. Quite probably they had no idea of that possibility. But it came. So it’s very hard to know the destiny of what you do. I do it because I like what I do, and because I am interested in ideas and the history of ideas. I am not a utilitarian, so I don’t care to know if it is useful or useless; this is not my concern.

Q: Have you seen your ideas change, or have they remained the same?

B: They are always undergoing change. When we started this school of thought or trend, we had no literal catechism. It was not dogma, but rather it was a mixture of conviction and empiricism. So we have changed on some points. Some of the ideas we have developed have revealed themselves to be not very good, or perhaps what might be called “dead ends.”

Q: Can you give an example of a “dead end?”

B: Yes. For example, 20 or 25 years ago I was much more of a positivist than I am today. I remember that I devoted an issue of Nouvelle Ecole to the philosophy of Bertrand Russell, for example. And there appeared plenty of things against such strange people as Martin Heidegger and so on. But 20 years later I devoted an issue of Nouvelle Ecole to Heidegger, one that was very favorable to his philosophy.[17] This is, of course, just one example. That doesn’t mean that we have changed everything; that would be stupid, of course. But it’s a living school, like a living organism. You have to retain something and to work deeper on those things, but some things you have to abandon because they are simply false. Well, we don’t want to repeat variations around the same theme year after year.

Q: How would you assess the significance of the Nouvelle Droite?

B: Well, first I have to spell out my concerns with some words – the very name: the New Right. I don’t like it for several reasons. First, you should know that we did not invent this name. It was given to us. About ten years after the first appearance of journals such as Nouvelle Ecole and Eléments, there was a very large-scale mass media campaign in which the expression, “The New Right,” was produced by people who were quite outsiders from our circle. We attempted to change it. We tried to say that it’s not “The New Right” but, “A New Culture.” Yet “new culture” is not a very clear term. And, in our modern society, when you have been given a wrong label, it just sticks.

I don’t like this term because, first of all, it gives us a very political image, because “right” is a political term. Therefore, when you speak about “the New Right,” the people who do know nothing about it immediately believe it is some kind of political party. Of course, it is not. We are a theoretical and cultural movement.

At the same time, there is something that is clearly political – particularly in America – with this “New Right” name. Even though it is in different countries, people thus start to believe that this is the same thing. Based on everything I know about it, the so-called New Right in America is completely different from ours. I don’t see even a single point with which I could agree with this so-called New Right. Unfortunately, the name we now have gives rise to many misunderstandings.

While I cannot say that, after these many years, the [European] New Right is accepted everywhere – that is obvious – I can say that, in ever wider circles, it is accepted in France as a part of the cultural-political landscape. Debate and discussion here during the last two decades could not be thought of without the contribution of the New Right. Moreover, it is because the New Right has taken up particular themes that particular debates have taken place at all. I refer, for example, to discussions about the Indo-European legacy in Europe, the Conservative Revolution in Germany, about polytheism and monotheism, or about I.Q. – heredity or environment (which is partly a rather false dichotomy), participatory democracy, federalism and communitarian ideas, criticism of the market ideology, and so forth. Well, we were involved in all these issues. As a result, I think, the situation in France today is a bit different.

When the New Right first appeared in France in 1968, the times were completely different. For me, the ideology of the extreme left was a kind of model or standard. Marxism, Freudianism and so on, were everywhere. In the years since then, all of those “ideological churches” have fallen apart. Very few people in France today would describe themselves as Marxists. Jean-Paul Sartre, a very famous philosopher, died [in 1980] without any particular ideological legacy. The landscape had already completely changed. I would say that there are no longer are any ready-made ideas. All of the grand ideologies or ideological characters have more or less disappeared. More and more the intellectuals have to look for something new; something original and beyond the ready-made solutions of the past.

We must accept, first of all, the fact that we are out of the post-World War II period, and that we have entered a new world epoch – that there are new frontiers, both in political and ideological terms. And we don’t want to impeach people simply because they come from different ideological starting points. So it is clear that the times have changed. And always when the times are changing, some people want to keep things as they were. Opposition to the New Right is often “wet” or undogmatic, which means more liberty for everyone. I mean, for example, that there are people in the leftist circles who are willing to discuss issues with me, or to be published in Krisis, the journal I started in 1988. (Of course, there are other leftists who absolutely refuse to do so).[18]

In the last several years, the New Right has produced numerous articles rejecting the ideal of the economy as the destiny of society and criticizing alike conservatism, liberalism, socialism, and Marxism – in short, all of the “productivistic” ideologies that see earning money and possessing wealth as the key to human meaning and happiness. All these ideologies fail to confront the main issue of individual and collective meaning: What are we doing here on earth? So we have published numerous books and articles against consumerism, the commodity-driven life, or the idéologie de la marchandise. Of course, such themes are more or less a bridge between people coming from the Right and coming from the Left. So you have also the new phenomenon of the “Greens,” which, again, is a bit different in France and America. For example, we have in France a “green” ecology movement – a political party, in fact – that describes itself as neither Right or Left.

Thus we have today in Europe numerous new political parties – ecological, cultural identity and region-oriented. While these are, of course, different options, each of them goes beyond the idea of Right versus Left. Each reflects the consequences of the decay of the traditional nation-state. Each is trying to find, beyond individualism, some kind of community. While each has a different base, of course, there is also a common idea, because we can no longer continue to live in an age of narcissism, consumerism, individualism, and utilitarianism.

Q: What would you say is the political importance today of the so-called New Right? Does it have any direct or tangible political significance?

B: No, I could not say that. I know people in probably every political party in France, ranging from the Front National to the Communist Party. The New Right does not have a direct influence. The influence that the New Right has had is clearly in terms of the theoretical and cultural. The discussions we have generated have had an impact on the new social-political movements. But you know, it is very difficult even to try to isolate these influences. Most of the time, I think, the ideas go underground. Nietzsche once said that ideas come “sur des pattes de colombe” – on the feet of a dove.

All the same, one can tell that there is currently some kind of influence by us on the new social or political movements in Europe, such as the identity parties, the regional parties, and the Green parties. Many of these people read what we produce, but it is hard to say just what they do with it. You never know not only just what influences your ideas have, but what becomes of ideas between their origin and their manifestation [in action]; they are always twisted. Even when you have people who say, “I agree with you, I like what you do,” the use they make of your ideas is, of course, sometimes not exactly what you had in mind.

Q: Can you give an example of where you feel the ideas of the movement have been misused? Does this bother you?

B: In a way. Yes. I could say the Le Pen movement [of the French Front National]. This doesn’t mean that the Le Pen movement grew primarily from New Right ideas, but it is clear that when the New Right spoke about the necessity of retaining collective identity, for example, this had an impact. So it might be confused a bit with quite a different philosophy, which is more xenophobic against immigrants, and so on. But this is not the position of the New Right. Our national identity is not in danger because of the identity of others. We say, instead, “Here we are. We have to fight together against the people who are against any form of any identity.” You see what I mean? Criticizing uncontrolled immigration doesn’t mean criticizing immigrants.

Q: So it is not so much a question of one identity in conflict with another, but a more fundamental question of whether it is possible to have any kind of identity?

B: Yes, I think it is possible to make a coalition of all kinds of people who want to retain identity against a world trend that dissolves every form of identity, through technology, the economy, a uniform way of life and consumerism around the world. People such as Le Pen say that, either way, we are losing our identity because of the immigrants. I believe that we are not losing our identity because of the immigrants. We have already lost our identity, and it is because we have already lost it that we cannot face the problem of immigrants. You see, that is quite a great difference of views.

Q: Isn’t this idea of forming a coalition a philosophical one? In reality, doesn’t the nation-state demand that one have citizenship and through this one is granted an identity? If you do away with the nation-state, your idea is possible, but is it possible within the nation-state? Doesn’t the nation-state require a competition or conflict between identities?

B: I think that the nation-state is slowly disappearing. It exists, of course, formally – I don’t want to say that France or Germany or Spain is going to disappear. But it is it not the same kind of society. First, you can see that every Western society lives in more or less the same way, whether it is a republic, a democracy, a constitutional monarchy, and so on. Second, we have unification through the media, television, and consumerism; so that’s the same way of life. After that you have the building of the so-called European Community or European Union. So the nation-state is slowly disappearing. This process is very complex, of course, because the nation-state retains authority in many fields. And sometimes it is good that it retains some authority. Still, it is clear to us that, to use a popular expression, the nation-state is too big for the little problems, and too little for the big problems.

Q: Are you saying that the nation-state is obsolete as a basis for responding to problems and for creating identity. Are you saying that it cannot exist in a healthy form?

B: You can’t retain a commonplace or, vulgar – as it were – attitude, or a mere identity on paper. It is necessary to really live organically, not in some theater. Thus, in France today, we need more small-scale organic units and regions. Historically, you must not forget, France is the very model of the nation-state. And the French nation-state was organized first through the kings, and then through Revolution [1789–1792], that is, through Jacobinism. (Of course this process existed before the Revolution; de Toqueville saw this very clearly.)

French unity was made on the ruins of the local traditions of local languages. In France today you have only one official language: French. In fact, though, eight different languages are still spoken, even if not by very many people, including Corsican, Flemish, German, Basque, and Breton.

Q: Are you saying that the idea of the nation-state today is an idea of decadence? What is the source of this decadence? Is it the nation-state itself?

B: No. I think the nation-state is just a by-product. You can have the same decadence in countries that are supposed to be more federal, such as the United States. It is not just a matter of the nation-state of the French model. I think that the decay began very early, quite probably at the end of the Middle Ages or even earlier. Of course you can always go back to some earlier roots. But it is the birth of modernity. Modernity was also the beginning of individualism; the rejection of traditions; the ideology of progress; the idea that tomorrow will be better than yesterday just because it is tomorrow; that is, something that is new is better just because it is new; and then the ideal of a finalized history; that all humankind is doomed to go in the same direction.

Along with this is the theory of “steps”: that some people are a bit advanced while others are a bit late, so that the people who are advanced have to help those who are not. The “backward” people are supposed to be “lifted up” in order to arrive at the same step. This is the Rostows’ theory of “development.”

With this comes an ever more materialistic attitude, with the goal of all people becoming affluent. This in turn means failure to build a socially organic relationship, of losing the more natural links between people, and mass anonymity, with everyone in the big cities, where nobody helps anybody; where you have to go back in your home to know the world, because the world comes through the TV. So this is the situation of decay. Political, economic and technological forces try to make a “One World” today in much the same way that the French state was built on the ruins of the local regional cultures. This “One World” civilization is being built on the ruins of the local peoples’ cultures. So it is that, in the wake of the fall of Communism, the so-called “Free World” realizes this, and that it is not so “free” after all. We seemed free when compared to the Communist system, but with the disappearance of that system, we no longer have a basis by which to compare ourselves.

In addition, to be “free” can mean different things: to be free for doing something, for instance, is quite different than to be free not to do something.

Q: In your writings you have mentioned that it is important to have an enemy. Were you implying that with the fall of Communism, because there is no longer a clear enemy, there can be no clear identity?

B: Not exactly. It’s clear that you can have an identity without an enemy; but you cannot have an identity without somebody else having another identity. That doesn’t mean that the others are your enemies, but the fact of the otherness can become in certain circumstances, either an enemy or an ally. I mean that if we are all alike – that we if there is just “One World” – we no longer have any identity because we are no longer able to differentiate ourselves from others. So the idea of identity is not directly connected to an enemy; the idea of an enemy is connected with the collective independence; that is, collective liberty.

There are many definitions of “the enemy,” of course. Traditionally, the enemy is a people that makes war against you. But today’s wars are not always armed conflicts. There can be cultural wars or economic wars, which are conducted by people who say they are your friends. You could say that a basic definition of the enemy is any force that threatens or curtails your liberty. Each nation must define this for itself. What is a good basis for determining this today? I think this must be done on the level of Europe itself, because the nation-states are too small for this. When Soviet Communism disappeared, it seemed to give way to a worldwide wave of liberalism. In the view of some, it means the “end of history.” I do not believe that history is finished. I believe that history is just at the point of a new beginning.

We have to organize the world, not on the basis of a “One World” logic, but in very large zones or areas, each more or less “self-centered” or self-sufficient. The United States has already understood this, I think, in creating a free trade zone with Canada and Mexico. Japan already has zones of influence in Southeast Asia. Here in Europe we must have our own way of life, which is not the way of life of the Japanese or the Americans, but is rather the European ways of life. I don’t think that these ways of life have to be hostile towards others. Hopefully not. But it has to be aggressive against those who intend to keep Europeans from living their our own way of life.

Q: Does Europe have the strength or the ability to resist such forces?

B: The ability, yes. But the will? In today’s world, you first of all have to resist from both an economic and a cultural point of view. By cultural I mean very popular mass media and its powers. Today, if you turn on your radio in France, nine times out of ten you will hear American music. In America, when you turn on your radio you will hear only American music. This problem, which is also true for the cinema, is a kind of monopoly; culture always from the same source, and so consistent. You may ask if it is possible to resist this kind of invasion. Considering the enormous budgets of these American films, to counter this we may have to act together, rather than in a single country.

Now I am not suggesting that in France we should hear only French music. This would be ridiculous. We have to be open to others. The problem is that there are more countries in the world besides France and America; I would also enjoy hearing other varieties as well. I am not for a closed society. I would be very malheureux – unhappy – to get only French films, French sounds. I very much enjoy foreign products. But I wonder why we do not see Danish, Spanish, Russian or Dutch cultural products in France, though those countries are quite close by. Instead we always have the same American imports. Sometimes they are good, but most of the time I would say that they are not. So what happens, for example, when the Japanese and the French, the people in South Africa and the villagers in Kansas, all receive the same Rambo message? Is that good for civilization or not? This is the question: the quality of the product.

Q: I have heard that in France one week is set aside each year when American films cannot be shown. Is that true?

B: No, you are referring to something quite different: by law in France, TV channels cannot broadcast too many films on Saturday night. This law is supposed to help the French film industry, even though it has absolutely nothing to do with the origin of the films. This is a situation peculiar to France, even though we still have a good French film industry, which is greatly appreciated in other European countries. This means that television has not entirely killed the French cinema. The situation is quite different in Italy and Germany, which is very dramatic when you consider the former quality of the Italian or German films.

In another way, though, I think that “popular [mass] culture” in France is probably worse than in Italy, Spain, Germany, or other lands. I travel a great deal. I think that there is an Italian people, a German people, and that even with many foreign films, they are not affected in the same way as the French. When you are in Germany, or Italy, or Spain, or England, people in each country live a bit differently.

This is not so true in France, I think. The main reason is that so many more people live in large cities. Eighty-five per cent of the French people live in the main cities now. So the French countryside is a desert, a social desert.

Q: Are you saying then that France is more vulnerable to this cultural invasion from America then, for example, Italy or Germany?

B: I understand very well the market decision of the Disney company people to locate “Eurodisney” in France (even though this has proven to be a financial failure). The threat is that today every decision is a market decision. This is Americanism. A country has a right to make a decision that is not a market decision, and even against the market, because the laws of the market are not the laws of life.

Q: Although you have already indicated that this is not your primary concern, let me now go back for a moment to a question of practical politics. I want to know your ideas about how to strengthen resistance in this cultural war. What can be done that is not now being done?

B: In history you have always two kinds of factors. The first is the conscious will of the people to do something. I must say that in Europe this will is very weak today, and lacking in intensity. The second factor is that things happen outside of the will of anybody. Consider the fall of the Berlin Wall. Of course, the Russians had the will to say “Okay, you can tear it down now.” But in Germany, until that moment, nobody was really willing to tear down the wall. Some Germans hoped to see it come down, and others said that maybe after five, ten or 15 years a confederation [of the two German states] would arise. So if you consider the trend throughout Europe, it is more or less the same: the people and their governments talk and talk, and do nothing! The war in the former Yugoslavia is the best example of this I see.

A principle of conflicting interests is also involved here. Most European governments want to conclude a free trade agreement, based on the United States model. It is a fact, of course, that the interests of Europe, America, and Japan are no longer convergent. But there are common interests of each with regard to the Third World countries, where the people are paid so low that they can produce everything for almost nothing. If it is possible to manufacture a pair of shoes in the Third World for one franc, it is done. As a result, we now have all the problems of unemployment here. Experts predict that within two years there will be 24 million jobless people in the countries of the European Community. Never in the entire world history of capitalism have we seen that. In such a situation you cannot calmly sit in your chair and say, “Well, let’s wait a bit more.” You have to react, because the need to deal with such a situation becomes so great. Each nation must protect its own interests. Free trade agreements must be limited. It is the same, of course, for America, which protects its own industries while denying this same right to Europe.

I think that these forces will more likely produce a world of large-scale competing units than one in which each nation is preserved. I do not think this trend reflects the will of the people. I mean that the process seems to be going on as a result of certain factors that have nothing to do with what people want.

Q: This process of forming these new and larger entities is not just a natural accident of history. Doesn’t it require conscious organization of some kind? Or do you think it is a sort of natural historical development?

B: I don’t believe there is much natural development in history. You have to will something, and yet, will alone is not sufficient, of course. You must have the necessary pre-conditions; so it is an equilibrium between what is wanted and what is possible. Politics is, as the saying goes, “the realm of what is possible,” that is, between what is a necessity and what is a possibility. So, it is not natural. But of course, when you have a certain situation like today, you can predict that things are likely to take this or that direction. Change can also be reversed, of course.

For example, the main characteristic of the current state of world politics is that, in the minds of most politicians, that Berlin Wall has still not fallen. They still analyze the world on the basis of former conceptions, former ideas, because that view worked in the past. We have a new state of the world, but we haven’t yet adapted to it. So we continue to reason on the basis of the world order created in 1945 – as if that political, economic and cultural order will last forever. So, I think that while world conditions have begun to change, our mind-set and perceptions have not changed.

Q: Some analysts predict the overthrow of an obsolete “political class.” Do you see a new awareness regarding the need to replace the ruling class?

B: One thing that is quite new in the present period is this: in former times, when the people disagreed massively with the ruling powers, they would overthrow them, and there would be an explosion. Today, though, in the Western world we are in a period not of social or political explosion, but more in an epoch of implosion. The people disagree with the political class, but they do not try to overthrow it; they don’t try to change the regime. They merely turn away.

So this is a time of retreat, of flight, of withdrawal. People try to live and organize their own lives. They don’t participate in elections. That’s why you see so many new self-assertive social movements, which we in France sometimes call the “new tribes.” This term often has a pejorative meaning, but in general there is something positive here.

Before the emergence of the nation-state, people were, of course, organized into tribes. Tribes are now returning in the name of communities, or something akin to that. In France we do not have this phenomenon on the political level to the degree that it has been occurring in Italy, notably with the regionalist Lega Nord. Here in France, what you can see is that fewer people are voting. Now more than one-third of the electorate has stopped going to the polls. (The exception is presidential elections, because these are more personalized.) And another third of the electorate votes for non-conformist parties – the ecologists, Front National, regionalists, and so on – while only one-third still votes for the older, “classical” parties.

A problem in France is that our representative system provides no legal place for opposition political forces. Today we have a more or less conservative majority, which got 40 percent of the vote in the general election. But with 40 percent of the vote, they gained more than 80 percent of the parliament seats. The Front National, with three million votes, got zero seats, and the ecologists, with two million votes, likewise got zero seats. When you arrive at a point of such distortion, you realize that the political system no longer works. Of course, this is one major reason why people don’t bother to vote anymore. Why go to vote when you are sure that you will get no say at all?

Q: It appears to be very much the same in the United States.

B: For me, as a European observer, the American two major-party system always makes it difficult for any third party to arise. It is very strange. In Europe we have evolved a broader spectrum of options, I think. While it is sometimes difficult even for Americans to see any real difference between the Republican and Democratic parties, for me it is almost impossible. Each is really interested only in more business and economic efficiency – frankly, I don’t see any difference. For me it is a one-party system with two different factions.

Q. So you see this American monopoly or hegemony as the key problem? Are you implying that it is not so much the contact as such, which may have some good elements, but mainly that there is no choice?

B: These are two different problems. Of course, there is the problem of monopoly – that’s clear – but if the products were quite good – after all I like quality, too, even if it comes from the outside. The Romans took everything from classical Greece and it was not so bad, after all.

I enjoy visiting the United States, because it is always very interesting. Although I am very critical, of course, of the content of capitalist values, there are some things in America that I like very much: everything works much better than here in Europe! But is efficiency an ideal? And what price do you have to pay for this efficiency? You can be rich, but also have an empty life. Another problem, I think, is that American society – for us, America is more a society than a nation or a people – is to a large extent a product of its Puritan origins. This idea that all people are born free and equal, that America is a new promised land, with people quoting the Bible, can be seen in the spirit of the American Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution.

Q: Why don’t you consider America a nation?

B: It’s a special kind of nation, if you will. There is a very strong American patriotism, of course – and we have seen many examples of that in history. But because it is more a mixture of such different cultural and ethnic stocks, the United States of America is not what we in Europe regard as a traditional nation.

Throughout our conversation, de Benoist’s remarks left me with a certain ambivalence. He was identifying my own nation as the enemy of the very civilization from which America derived. Even when he tried to re-assure me that there was nothing personal in his critique of American culture, it was clear that he was marking out a battleground of antagonistic ideas. Those who value the cultural heritage of Europe would have to look beyond day-to-day political and economic disputes between the European Community and the United States to understand that much more is at stake here. Our discussion had touched on some of most critical issues of social identity and organization, with profound implications for cultural and collective survival.

Notes

| [1] | Philip Rees, Biographical Dictionary of the Extreme Right (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), p. 30. |

| [2] | Krisis, 5 impasse Carrière-Mainguet, 75011 Paris, France. |

| [3] | GRECE is an acronym of “Groupement de recherche et d’études pour la civilisation européenne.” (“Research and Study Group for European Civilization.”). Address: GRECE, B.P. 300, 75 265 Paris Cedex 06, France. Established in May 1968, GRECE was formally organized in January 1969. It characterizes itself as “an association of thought with intellectual vocation.” Its avowed goals, writes Sunic (p. 12), “are to establish an association of thinkers and erudites sharing the same ideals, as well as organize its membership into the form of an organic and spiritual working community.” The name is not accidental. It suggests the French name for Greece – “Grèce” – calling to mind Europe’s Hellenic and pre-Christian cultural heritage. |

| [4] | Against Democracy and Equality (196 + xii pages), by Tomislav Sunic, with a preface by Paul Gottfried, was published by Peter Lang of New York in 1990. |

| [5] | See the preface by P. Gottfried in T. Sunic, Against Democracy and Equality (1990), p. ix. |

| [6] | T. Sunic, Against Democracy and Equality (1990), pp. 19, 20. |

| [7] | T. Sunic (1990), p. 7 |

| [8] | Sunic comments (p. 99) that “The New Right contends that due to the legacy of fascism, many theories critical of egalitarianism have not received adequate attention on the grounds of their alleged ‘anti-democratic character’.” |

| [9] | T. Sunic (1990), pp. 104–105. |

| [10] | Sunic writes (p. 120): “Faced with immense wealth which surrounds him, a deracinated and atomized individual is henceforth unable to rid himself of the fear of economic insecurity, irrespective of the degree his guaranteed political and legal equality …. Now, in a society which had broken those organic and hierarchical ties and supplanted them with the anonymous market, man belongs nowhere.” |

| [11] | Quoted in: T. Sunic (1990), p. 107; In Benoist’s view, “People exist, but a man by himself, the abstract man, the universal, that type of man does not exist.” Moreover, contends Benoist, man acquires his full rights only as a citizen within his own community and by adhering to his cultural memory. (T. Sunic, p. 107); De Benoist also asserts that man can define his liberty and his individual rights only as long as he is not divorced from his culture, environment, and temporal heritage. (T. Sunic, p. 111.) |

| [12] | T. Sunic (1990), p. 103. |

| [13] | T. Sunic, pp. 103–105; From the perspective of the New Right, observes Sunic (p. 107), “Culture and history are the ‘identity card’ of each people. Once the period of the assimilation or integration begins to occur a people will be threatened by extinction – extinction that according to Benoist does not necessarily have to be carried out by physical force or by absorption into a stronger and larger national unity, but very often, as in the case today, by the voluntary and involuntary adoption of the Western Eurocentric or “Americano-centric” liberal model…. To counter this Westernization of nations, the New Right … opposes all univer-salisms.” |

| [14] | Quoted in: T. Sunic (1990), pp. 105, 106, 174 (n. 41). |

| [15] | T. Sunic (1990), pp. 65–70, 72. |

| [16] | T. Sunic (1990), pp. 153, 155–156. |

| [17] | Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) is one of this century’s most important philosophers. In several major works – especially Sein und Zeit [“Being and Time”] (1927) – he grappled with the spiritual basis of human experience, mounting a fundamental attack on what he termed “nihilistic rationalism,” which he saw as a product of an ever-advancing and dehumanizing technology. Because of his probing of the metaphysical issues of human existence, Heidegger is regarded as a major shaper of “post-modernism,” with its probing of the unconscious meaning and nature of human experience. Heidegger was a member of the National Socialist party from 1933 to 1945, while at the same time highly critical of National Socialist philosophy. The extent of his sympathy and support for the Hitler regime has been a subject of much debate. |

| [18] | In a much-discussed “Call to Vigilance” issued last summer, 40 French and Italian intellectuals warned of the growing acceptance of “right wing” views, particularly in European intellectual life. (Le Monde, July 13, 1993.) It was signed by such prominent figures as the “deconstructionist” Jacques Derrida. While it did not name names, this call was clearly aimed, at least in large part, at Alain de Benoist and the European New Right. It asserted the existence of a virtual conspiracy – “the extreme right’s current strategy of legitimation” – in which “the alleged resurgence of ideas concerning the nation and cultural identity” are promoted as a means of uniting the left and the right. “This strategy,” contend the signers, “also feeds on the latest fashionable theory that denounces anti-racism as both ‘outmoded’ and dangerous.” Many leftist intellectuals, it should be noted, publicly opposed this “Call to Vigilance,” regarding it as a new kind of “McCarthyism,” and ultimately this summer campaign proved utterly ineffectual. |

Errata

In the November-December 1993 issue, page 23, column one, the paragraph that begins “This case is particularly … ” should be indented.

In the November-December 1993 issue, page 67, column one, item No. 585, the author of Stalin's Apologist is not correctly identified. It should be simply S. J. Taylor.

In the January-February 1994 issue, page 30, column one, line 31, “May 1994” should read “May 1944.”

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 14, no. 2 (March/April 1994), pp. 28-37

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a