The Myth of a ‘Land Without People for a People Without Land’

Immediately following its publication in late 1995, Les mythes fondateurs de la politique israélienne (“The Founding Myths of Israeli Policy”), touched off a storm of controversy. Its octogenarian Communist-turned-Muslim author had taken aim at the historical legends cited for decades to justify Zionism and the Jewish state, including the most sacred of Jewish-Zionist icons, the Holocaust extermination story. (Les mythes was reviewed in the March-April 1996 Journal, pp. 35-36.)

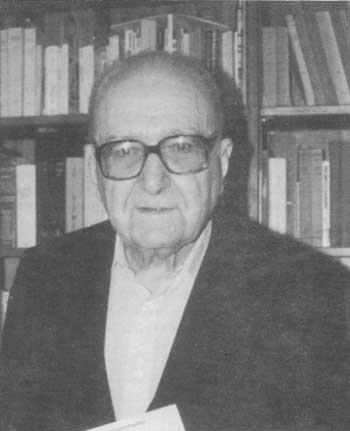

Roger Garaudy brought impressive credentials to this task. During the Second World War he was active in the anti-German Résistance (for which he was arrested and interned). Afterwards he joined the powerful French Communist Party, soon making a name for himself as a Communist deputy in the French National Assembly, and as a leading Marxist intellectual and theoretician. Later he broke with Communism and became a Muslim.

Soon after the publication of Les mythes, he was charged with violating France’s notorious Gayssot law, which makes it a crime to “contest” the “crimes against humanity” as defined by the Nuremberg Tribunal of 1945-46. A Paris court found him guilty and, on February 27, 1998, fined him 240,000 francs ($40,000). His trial and conviction for Holocaust heresy prompted wide international support, above all from across the Arab and Muslim world. (See: T. O’Keefe, “Origin and Enduring Impact of the ‘Garaudy Affair’,” July-August 1999 Journal, pp. 31-35; R. Faurisson, “On the Garaudy/Abbé Pierre Affair,” July-August 1997 Journal, pp. 26-28.)

In the following essay, adapted from the forthcoming IHR edition of The Founding Myths of Modern Israel, Garaudy takes on a key historical myth used to justify the founding of Israel, and its on-going policies of discrimination and oppression.

– The Editor

Zionist ideology rests on a very simple postulate: it is written in Genesis (15:18): “… the Lord made a covenant with Abraham, saying, ‘To your descendants I give this land, from the river of Egypt to the great river, the river Euphrates,…’”

Starting from this, without asking themselves what the covenant consisted of, to whom the promise had been made, or if the Lord’s choice had been unconditional, the Zionist leaders, even the agnostics and atheists, proclaimed: Palestine was given to us by God.

The statistics, even those of the Israeli government, show that 15 percent of Israelis are religious. This doesn’t stop the other 85 percent from also claiming that this land had been given to them by God … in whom they don’t believe.

The great majority of modern Israelis neither practice nor believe in a religion, while the different “religious parties,” despite comprising only a small minority of the Jewish population, play an important role in the state. This apparent paradox is explained by Nathan Weinstock in his book Le sionisme contre Israël (“Zionism Against Israel”):

If rabbinical obscurantism prevails in Israel, it is because the Zionist mystique is coherent only in light of the Mosaic religion. Take away the concepts of a “Chosen People” and a “Promised Land,” and the foundation of Zionism crumbles. This is why the religious parties paradoxically draw their strength from the complicity of agnostic Zionists. The inner cohesion of Israel’s Zionist structure has compelled its leaders to strengthen the power of the rabbis. It was the social democratic “Mapai” party, not the religious parties, which, at Ben-Gurion’s prodding, made courses in religious instruction an obligatory part of the school curriculum.

Weinstock, Le sionisme contre Israël, 1969, p. 315

This country exists as the fulfillment of a promise made by God Himself. It would be ridiculous to ask Him to account for its legitimacy. Such is the basic axiom formulated by Mrs. Golda Meir.

Le Monde, October 15, 1971

Begin restated this as:

This land has been promised to us and we have a right to it.

Begin’s statement at Oslo, Davar, December 12, 1978

If you have the Book of the Bible, and the People of the Book, then you also have the Land of the Bible – of the Judges and of the Patriarchs in Jerusalem, Hebron, Jericho and thereabouts.

Moshe Dayan, Jerusalem Post, August 10, 1967

Significantly, Ben-Gurion evoked the American “precedent” in which, over the course of a century, the frontier continuously advanced westward, all the way to the Pacific, where the “closing of the frontier” was proclaimed, thanks to the success of the “Indian wars” in driving off the original Americans and seizing their lands.

Ben-Gurion made it very clear:

To maintain the status quo will not do. We have set up a dynamic state, bent on expansion.

Ben-Gurion, Rebirth and Destiny of Israel, p. 419

Zionist policy has corresponded to this singular theory: take the land and drive out the inhabitants, as did Joshua, the successor to Moses.

Menachem Begin, the Israeli leader most profoundly imbued with biblical tradition, declared:

Eretz Israel will be restored to the people of Israel. All of it. And for ever.

Begin, The Revolt: The History of Irgun, p. 33

Thus, from the outset, the State of Israel places itself above all international law.

Imposed on the United Nations May 11, 1949, by the will of the United States, the State of Israel was only admitted on three conditions:

- That the status of Jerusalem would not be tampered with;

- That the Palestinian Arabs would be allowed to return to their homes;

- That the borders established by the partition decision would be respected.

Commenting on the UN resolution to “partition” Palestine, adopted long before Israel’s admission, Ben-Gurion declared:

The State of Israel considers the UN resolution of November 29, 1947, to be null and void.

New York Times, December 6, 1953

Echoing the concept of a parallel between American and Zionist expansion, General Moshe Dayan wrote:

Take the American Declaration of Independence. It contains no mention of territorial limits. We are not obliged to fix the limits of the State.

Jerusalem Post, August 10, 1967

Israeli policy corresponds precisely to the law of the jungle: the UN resolution mandating the partition of Palestine was never honored.

The resolution on the partition of Palestine, adopted by the UN General Assembly (at that time made up almost entirely of Western nations) on November 29, 1947, signaled the West’s designs on its “forward stronghold”: on that date, the Jews were 32 percent of the population and owned 5.6 percent of the land. Partition awarded them 56 percent of Palestine, including the most fertile land. The terms of the partition were agreed to by the General Assembly under pressure from the United States.

President Harry Truman exerted unprecedented pressure on the State Department. Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles wrote:

By direct order of the White House every form of pressure, direct and indirect, was brought to bear by American officials … to make sure that the necessary majority would be at length secured.

Sumner Welles, We Need Not Fail, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948, p. 63

The secretary of defense at that time, James Forrestal, confirmed:

… The methods that had been used … to bring coercion and duress on other nations in the General Assembly bordered closely on to scandal.

James Forrestal, Forrestal’s Memoirs, New York: Viking, 1951, p. 363

The power of private monopolies was mobilized.

Drew Pearson, in the Chicago Daily News of February 9, 1948, provided some details:

Harvey Firestone, owner of rubber plantations in Liberia, used his influence with the Liberian government …

Beginning in 1948, the Israelis violated these pro-Zionist decisions.

The Israeli leaders took advantage of the Arabs’ refusal to accept such injustice by grabbing new territories, notably Jaffa and Acre – so much so that by 1949, the Zionists controlled 80 percent of the country and 770,000 Palestinians had been driven out.

The method was terror.

The most striking instance was at Deir Yassin, on April 9, 1948: 254 inhabitants of this village (men, women, children, and the elderly) were massacred by troops of the Irgun, led by Menachem Begin, by methods indistinguishable from those the Nazis used at Oradour.

In his book The Revolt: The History of Irgun, Begin wrote that there would have been no security for the State of Israel without the “victory” of Deir Yassin (p. 162). He added:

Meanwhile, the Haganah was carrying out successful attacks on the other fronts … The Arabs began fleeing in panic, shouting: “Deir Yassin!”

Begin, Revolt, p. 165

Any Palestinian who left his residence before August 1, 1948 was considered “absent.”

In this way, two thirds of the land owned by the Arabs (70,000 hectares out of 110,000) was confiscated. When the law on landed property was passed in 1953, compensation was fixed at the value of the land in 1950; in the interim the Israeli pound had dropped to a fifth of its value.

Moreover, from the beginning of Jewish immigration (here again in the truest colonialist style), land was bought from feudal, non-resident landowners (the “effendis”). Through arrangements between the former masters and the new occupants, the poor peasants, the fellahin, who had no say in the matter, were evicted. Deprived of their land, there was nothing left for them but to flee.

The United Nations appointed a mediator, Count Folke Bernadotte of Sweden. In his first report, Count Bernadotte wrote:

It would offend basic principles to prevent these innocent victims of the conflict from returning to their homes, while Jewish immigrants flood into Palestine and, furthermore, threaten, in a permanent way, to take the place of the Arab refugees who have been rooted in this land for centuries.

He described

Zionist pillaging on a grand scale and the destruction of villages without apparent military necessity.

This report (UN Document A, 648, p. 14) was filed on September 16, 1948. On September 17, 1948, Count Bernadotte and his French assistant, Colonel Serot, were assassinated in the part of Jerusalem occupied by the Zionists.

It was not the first Zionist crime against someone who criticized their treachery.

Lord Moyne, the British secretary of state in Cairo, declared on June 9, 1942, in the House of Lords that the Jews were not the descendants of the ancient Hebrews and that they had no “legitimate claim” on the Holy Land. A proponent of curtailing immigration into Palestine, he was accused of being “an implacable enemy of Hebrew independence.”

In Isaac Zaar, Rescue and Liberation: America’s Part in the Birth of Israel, New York: Bloch, 1954, p. 115

On November 6, 1944, Lord Moyne was assassinated in Cairo by two members of the Stern Gang (Yitzak Shamir’s group).

Years later, on July 2, 1975, The Evening Star of Auckland revealed that the bodies of the two executed assassins had been exchanged for twenty Arab prisoners for burial at the “Heroes’ Monument” in Jerusalem. The British government deplored that Israel should honor the assassins and make heroes of them.

On July 22, 1946, the wing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem occupied by the British civil and military authorities for Palestine was blown up, causing the deaths of nearly a hundred people, British, Arabs, and Jews. The Irgun, Begin’s group, had carried out the attack, and claimed responsibility.

The State of Israel replaced the British colonialists, then used their methods. For example, agricultural aid for irrigation was distributed in a discriminatory fashion, so that Jewish landholders were systematically favored. Between 1948 and 1969, the area of irrigated land rose, for the Jewish sector, from 20,000 to 164,000 hectares; for the Arab sector, from 800 to 4,100 hectares. The colonial system was thus perpetuated, growing even more oppressive: Doctor Rosenfeld, in his book Arab Migrant Workers, published by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 1970, recognized that Arab agriculture had been more prosperous during the British mandate than it was under the Israelis.

Segregation also figures in housing policy. The president of the Israeli Human Rights League, Doctor Israel Shahak, a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, relates in his book Le racisme de l’État d’Israël (“The Racism of the Israeli State”) (Paris: G. Authier, 1975, p. 57), that in Israel there are whole towns (Carmel, Nazareth, Illith, Hatzor, Arad, Mitzphen-Ramen, and others) where non-Jews are forbidden by law to live.

In cultural matters the same colonialist spirit reigns.

In 1970, the Minister of National Education proposed two different versions of the prayer “Yizkor” for high school students. One version proclaimed that the death camps had been built by “the diabolical Nazi government and the German nation of murderers.” The second version alluded more generally to “the German nation of murderers….” Both contain a paragraph … calling on God “to avenge before our eyes the blood of the victims.”

“Ce sont mes frères que je cherche,” Ministry of Education and Culture, Jerusalem, 1990

This culture of racial hatred has borne fruit:

“In the wake of Kahane, we heard more and more about soldiers who, exposed to the history of the Holocaust, were planning all sorts of ways to exterminate the Arabs,” recalled education-corps officer Ehud Praver. “It concerned us very much, because we saw that the Holocaust was legitimizing the appearance of Jewish racism. We learned that it was necessary to deal not only with the Holocaust but also with the rise of fascism and to explain what racism is and what dangers it holds for democracy.” According to Praver, “… too many soldiers were deducing that the Holocaust justifies every kind of disgraceful action.”

Tom Segev, Seventh Million, p. 407

The problem had been expressed very clearly even before the State of Israel came to be. The director of the Jewish National Fund, Yossef Weitz, wrote in 1940:

It should be clear to us that there is no room for two peoples in this country. If the Arabs leave it, that will satisfy us … There is no other way but to remove them all; there must not be a single village left, or a single clan … It must be explained to Roosevelt and to all the heads of friendly states that the land of Israel is not too small if all the Arabs leave and if the borders are pushed back a little to the north, as far as the Litani, and toward the east, to the heights of the Golan.

Yossef Weitz, Diary and Letters to My Sons, Tel Aviv, 1965

In the major Israeli newspaper Yediot Aharonot (July 14, 1972), Yoram Ben-Porat forcefully reminded Israelis of the Zionist objective:

It is the duty of Israeli leaders to explain clearly and courageously for public opinion a certain number of facts which time causes to be forgotten. The first of these is that there is no Zionism, colonization or Jewish State without the eviction of the Arabs and the expropriation of their land.

Here again we observe the most exacting logic of the Zionist system: How to create a Jewish majority in a country populated by a native Palestinian Arab community?

Political Zionism provided the only solution possible within the framework of its colonialist program: create a settler colony while driving out the Palestinians and promoting Jewish immigration.

Driving out the Palestinians and taking over their land was a deliberate and systematic undertaking.

At the time of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the Zionists possessed only 2.5 percent of the land; at the time UN resolution to partition Palestine in 1947, they had 6.5 percent. By 1982, they possessed 93 percent.

The methods used to dispossess the natives of their land have been those of the most ruthless colonialism, with Zionism adding an even more pronouncedly racist taint.

The first stage bore all the hallmarks of classic colonialism: exploitation of the local work force. This was Baron Édouard de Rothschild’s metier: just as he had previously exploited the cheap labor of the fellahin on his vineyards in Algeria, in Palestine he simply enlarged his sphere of activity, exploiting other Arabs in his vineyards there.

A turning point occurred with the arrival from Russia of a new wave of immigrants following the failure of the Revolution of 1905. Instead of carrying on the fight there, side by side with other Russian revolutionaries, the deserters of the defeated revolution imported a strange Zionist socialism into Palestine. They created production and service cooperatives and agricultural kibbutzes, excluding the Palestinian fellahin in order to create an economy based on a Jewish working and agricultural class. From a classical colonialism (of the English or French type), Palestine passed to a settlement colony in the logic of political Zionism, involving an influx of immigrants “for” whom, and “against” no one (accordingly to Professor Klein), land and work had to be provided. From this point on, it was a matter of replacing the Palestinian people with another, and, naturally, of taking their the land.

The starting point of this great operation was the creation, in 1901, of the Jewish National Fund, which had a feature novel even to settler colonialism: the land which the JNF acquired could not be resold, or even rented, to non-Jews.

Two other laws concern the Keren Kayemet (Jewish National Fund; law passed on November 23, 1953) and the Keren Hayesod (Foundation Fund; law passed on January 10, 1956). “These two laws,” writes Professor Klein, “permitted the transformation of these societies, which found themselves benefitting from certain privileges” (Klein, Caractère juif, pp. 20-21). Without enumerating these privileges, he introduces, as a simple “observation,” the fact that lands obtained by the National Jewish Fund were then declared “Lands of Israel,” and a law was enacted to decree the inalienability of these lands. This law is one of Israel’s four “fundamental laws” passed in 1960 (elements of a future constitution, which still does not exist, fifty years after the creation of Israel). It is unfortunate that the learned lawyer, usually attentive to detail, made no comment on this “inalienability.” He does not even define it: a piece of land “reclaimed” by the Jewish National Fund (“land redemption”) is a land which has become “Jewish”; it can never be sold to a “non-Jew,” nor rented to a “non-Jew,” nor worked by a “non-Jew.”

Can it be denied that this fundamental law is discriminatory?

Israel’s agrarian policy is one of systematic plundering of the Arab peasantry.

The property law of 1943, on expropriation in the public interest, is a relic from the time of the British mandate. This law is perverted from its original intent when it is applied in a discriminatory way, as, for example, in 1962, when 500 hectares were expropriated at Deir El-Arad, Nabel and Be’neh, where the “public interest” consisted of creating the town of Carmel, which was reserved exclusively for Jews.

Another procedure involved the use of “emergency laws,” decreed in 1945 by the British against both Jews and Arabs. Law 124 gives the military governor the authority, this time under the pretext of “security,” to suspend all civil rights, including freedom of movement. The army has only to declare an area off limits, “for reasons of state security,” in order to prevent an Arab from entering his land without authorization from the military governor. If authorization is refused, the land is then declared “uncultivated” and the ministry of agriculture can “take possession of uncultivated land in order to ensure its cultivation.”

When the British enacted this savagely colonialist legislation to fight Jewish terrorism in 1945, the lawyer Bernard (Dov) Joseph, protesting against this system of “arbitrary warrants,” declared:

Are we all to be subjected to official terror?… No citizen can be safe from imprisonment for life without trial … the power of the administration to exile anyone is unlimited … it is not necessary to commit any type of infraction, a decision made in some office is sufficient …

The same Bernard (Dov) Joseph, after he became Israeli minister of justice, applied these laws against Arabs.

J. Shapira criticized the British emergency laws at the same protest meeting at which Joseph spoke out, on February 7, 1946, in Tel Aviv (Hapraklit, February 1946, pp. 58-64), declaring even more forcefully: “The order established by this legislation is without precedent in civilized countries. There were no such laws even in Nazi Germany.” The self-same Shapira became the State of Israel’s chief prosecutor, then its minister of justice, and enforced the same laws he had denounced, against the Arabs.

To justify the permanence of these repressive laws, “the state of emergency” has not been lifted in the State of Israel since 1948.

Shimon Peres wrote in the newspaper Davar (January 25, 1972):

The use of Law 125, on which military government is founded, follows directly from the struggle for Jewish settlement and immigration.

The 1948 law on the cultivation of fallow lands, amended in 1949, is even more repressive: without so much as the pretext of “public utility” or “military security,” the minister of agriculture can requisition any abandoned land. The massive exodus of Arabs fleeing Israeli terror tactics, such as at Deir Yassin in 1948, Kafr Kassem on October 29, 1956, or the “pogroms” of “Unit 101,” created by Moshe Dayan and long commanded by Ariel Sharon, “liberated” vast areas. Cleared of their Arab owners or cultivators, they were handed to Jews.

The mechanisms for the dispossession of the fellahin were completed by the law of June 30, 1948; the emergency decree of November 15, 1948 on property of “absentees”; the law relating to lands of “absentees” (March 14, 1950); the law on the acquisition of land (March 13, 1953); and a whole arsenal of measures tending to legalize theft by pressuring the Arabs to leave their land in order to establish Jewish colonies, as Nathan Weinstock makes clear in Le sionisme contre Israël.

To obliterate even the memory of the Palestinian agricultural population and to give credence to the myth of the “desert,” the Arab villages were destroyed: their homes, their fences and even their graveyards and tombs. In 1975, Professor Israel Shahak gave, district by district, a listing of 385 Arab villages destroyed, bulldozed, out of the 475 that had existed in 1948.

To convince us that before Israel, Palestine was a “desert,” hundreds of villages were razed by bulldozer with their houses, their fences, their graveyards and tombs.

Shahak, Racisme, pp. 152ff.

The Israeli settlements have continued to multiply, with a new lease on life since 1979 on the West Bank, and, in accordance with the most classic colonialist traditions, the settlers are always armed.

The overall result is that after having expelled a million and a half Palestinians, “Jewish land,” – as the people of the Jewish National Fund call it – no more than 6.5 percent in 1947, today represents more than 93 percent of Palestine (of which 75 percent belongs to the state and 14 percent to the National Fund).

The outcome of this operation was remarkably (and significantly) summarized in the Afrikaner newspaper, Die Transvaler, well versed in matters of racial discrimination (apartheid):

What is the difference between the way in which the Jewish people struggle to remain who they are in the midst of non-Jewish populations, and the way Afrikaners are trying to remain what they are?

Henry Katzew, South Africa: A Country Without Friends, quoted in R. Stevens, Zionism, South Africa and Apartheid

The system of apartheid manifests itself in the regulation of individuals no less than it does in the appropriation of land. The “autonomy” which the Israelis want to grant the Palestinians is the equivalent of the “homelands” for the blacks in South Africa.

Analyzing the consequences of the Law of “Return,” Klein raises a question:

If the Jewish people are a large majority in the State of Israel, inversely, one can say that the entire population of the State of Israel is not Jewish, since the country has a sizeable non-Jewish minority, mainly Arab and Druze. The question which arises is to what extent the existence of a Law of Return, which favors the immigration of one part of the population (defined by its religious and ethnic affiliation), can not be regarded as discriminatory.

Klein, Caractère juif, p. 33

The author wonders in particular whether the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (adopted December 21, 1965, by the General Assembly of the United Nations) applies to the Law of Return.

By a dialectic of which we shall let the reader be the judge, the eminent lawyer concludes with this subtle distinction: in matters of non-discrimination,

a measure must not be directed against one particular group. The Law of Return was created for Jews who want to settle in Israel; it is not directed against any group or nationality. One cannot see how this law would discriminate.

Klein, Caractère juif, p. 35

For the reader who might risk being led astray by this, to say the least, audacious logic – which calls to mind the famous witticism that all citizens are equal but some are more equal than others – let us make the situation created by this Law of Return very clear. The Law of Nationality (5712/1952) specifies those who are not to benefit from the “right of return” in Article 3: “any individual who, immediately before the founding of the State, was a Palestinian subject, and who didn’t become an Israeli by virtue of Article 2” (which concerns the Jews). Those referred to by this circumlocution (and who are considered to have “never had any previous nationality,” in other words, were stateless persons) must prove they were living in Palestine over a given period (documentary proof is often impossible because the papers disappeared during the war and the terror which accompanied the establishment of the Zionist state). Failing this, in order to become a citizen, the “naturalization” route requires, for example, “a certain knowledge of the Hebrew language.” After which, “if he judges it useful,” the minister of the interior grants (or refuses) Israeli nationality. In short, in Israeli law, a Jew from Patagonia becomes an Israeli citizen the moment he sets foot in Tel Aviv airport; a Palestinian, born in Palestine, of Palestinian parents, can be considered a man or woman without a country. No racial discrimination “against” the Palestinians here – simply a measure “for” Jews!

It therefore seems difficult to contest the UN General Assembly’s resolution of November 10, 1975 (Resolution 3379-XXX) classifying Zionism as “… a form of racism and racial discrimination.”

In actuality, only a tiny minority of those who settled in Israel have come to fulfill “the promise.” The Law of Return has had very little effect. This is fortunate, because in every country of the world Jews have played an eminent role in every area of culture, science, and the arts, and it would be deplorable for Zionism to attain the objective the anti-Semites have longed for: to remove the Jews from their respective homelands in order to insulate them in a world ghetto. The example of the French Jews is significant: after the Évian agreements of 1962 leading to the independence of Algeria, of 130,000 the Jews who left Algeria, only 20,000 went to Israel, while 110,000 went to France. This emigration was not the result of anti-Semitic persecution, for the proportion of non-Jewish French colonists who left Algeria was the same. The reason for their departure was not anti-Semitism but the end of French colonialism. The Algerian French Jews experienced the same fate as the other French people in Algeria.

To summarize: Nearly all Jewish immigrants to Israel came to escape anti-Semitic persecution.

In 1880, there were 25,000 Jews in Palestine, out of a population of 500,000.

Starting in 1882, massive immigration began in response to the great pogroms of Tsarist Russia.

From 1882 to 1917, 50,000 Jews arrived in Palestine. Then, between the two wars, came the Polish immigrants and those from the Maghreb (the Mediterranean coast of Africa), who were escaping persecution.

The greatest number, however, came from Germany as a result of Hitler’s vile anti-Semitism. Altogether, almost 400,000 Jews arrived in Palestine before 1945.

In 1947, on the eve of the creation of the State of Israel, there were 600,000 Jews in Palestine, out of a total population of 1,250,000.

And so began the systematic uprooting of the Palestinians. Before the 1948 war, about 650,000 Arabs lived in the territory which was to become the State of Israel. In 1949, only 160,000 remained. Yet, due to a high birth rate, their descendants numbered 450,000 at the end of 1970. The Israeli Human Rights League revealed that between June 11, 1967 and November 15, 1969, more than 20,000 Arab houses were dynamited in Israel and on the West Bank.

At the time of the British census of December 31, 1922, there were 757,000 people living in Palestine, of whom 663,000 were Arabs (590,000 Muslim Arabs and 73,000 Christian Arabs) and 83,000 Jews (which is to say: 88 percent Arabs and 11 percent Jews). It is to be remembered that this so-called “desert” was an exporter of cereals and citrus fruits.

As early as 1891, one of the first Zionists, Asher Ginsberg (writing under the pseudonym Ahad Haam, “One of the People”), visiting Palestine, gave this account:

Abroad, we are accustomed to believing that Eretz-Israel is currently almost all desert, without cultivation, and that whoever wants to acquire land can come here and get as much as his heart desires. But the truth is nothing like this. Throughout the length and breadth of the country, it is difficult to find any fields which are not cultivated. The only non-cultivated areas are fields of sand and rocky mountains where only fruit trees can grow, and this, only after hard work and a lot of effort in clearing and reclamation.

Ahad Haam, Complete Works (in Hebrew), Tel Aviv: Devir, 8th edition, p. 23

In reality, before the Zionists, the “bedouins” (who were in fact settled farmers) were exporting 30,000 tons of wheat per year. The area of Arab orchards tripled between 1921 and 1942, that of orange and other citrus fruit groves multiplied seven-fold between 1922 and 1947, and production rose ten-fold between 1922 and 1938.

So rapid was the growth of Palestine’s orange industry that in 1937 the Peel Report, presented to the British Parliament by the secretary of state for the colonies, estimated that over the next decade Palestine would grow half the world’s winter oranges, as shown in the following table (the figures refer to crates of oranges):

Palestine 15 million United States 7 million Spain 5 million Other Countries (Cyprus, Egypt, Algeria, etc.) 3 million

Great Britain, Colonial Office, Palestine Royal Commission Report (“Peel Report”), (Cmd. 5479), 1937, chapter 8, § 19, p. 214

According to a US State Department study submitted to a congressional committee on March 20, 1993:

… more than 200,000 Israelis are now settled in the occupied territories (including the Golan Heights and East Jerusalem). They constitute “approximately” 13% of the total population of these territories.

Some 90,000 of them reside in 150 settlements on the West Bank, “… where the Israeli authorities control about half of the territory.”

“In East Jerusalem and in the outlying Arab suburbs of the city,” continues the State Department study,

… approximately 120,000 Israelis are settled in some twelve districts. In the Gaza Strip, where the Jewish State has confiscated 30 percent of an already over-populated territory, 3,000 Israelis reside in about 15 settlements. On the Golan Heights, there are 12,000, scattered among approximately 30 locations.

Le Monde, April 18, 1993

Le Monde cited the following report which originally appeared in the daily newspaper Yediot Aharonot, which has the largest circulation in Israel:

Since the 70’s, there has never been such an acceleration in construction within the territories. Ariel Sharon (Minister of Housing and Construction), is feverishly busy establishing new settlements, developing those which already exist, building roads and preparing new sites for construction.

Le Monde, April 18, 1993

(Recall that Ariel Sharon was the general in command of the invasion of Lebanon, who armed the Phalangist militias that carried out the massacres in the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila. Sharon turned a blind eye to these cowardly slaughters and was complicit in them, as even the Israeli commission appointed to investigate the killings determined).

The maintenance of the Jewish settlements in the occupied territories, their protection by the Israeli army and by armed settlers (like the frontiersmen of the American “Wild West” a century ago), makes any real Palestinian “autonomy” – and thus any hope for a genuine peace – impossible. They will remain impossible as long as the occupation continues.

The main thrust of colonialist settlement has been directed at Jerusalem and its environs, with the declared goal of making the decision to annex the whole of Jerusalem irrevocable – although that has been condemned unanimously by the United Nations (including the United States!).

The colonialist settlements in the occupied territories are a flagrant violation of international law, specifically the Geneva Convention of August 12, 1949, Article 49 of which stipulates:

The occupying power cannot undertake a transfer of a part of its own civil population into the territory which it occupies.

The pretext of “security,” such as from the “terrorism” of the intifada, is illusory: the statistics in this regard are eloquent:

1,116 Palestinians have been killed since the beginning of the intifada … on December 9, 1987, by shootings by soldiers, policemen or settlers. There were 626 deaths in 1988 and 1989, 134 in 1990, 93 in 1991, 108 in 1992 and 155 from January 1 to September 11, 1993. Among the victims have been 233 children under the age of 17, according to a study carried out by Betselem, the Israeli association for human rights.

Military sources give a figure of nearly 20,000 for the number of Palestinians wounded by bullets, and the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian refugees (UNRWA) gives a figure of 90,000.

Thirty-three Israeli soldiers have been killed since December 9, 1987: four in 1988, four in 1989, one in 1990, two in 1991, eleven in 1992 and eleven in 1993.

Forty civilians, mostly settlers, have been killed in the occupied territories, according to figures provided by the Army.

According to the humanitarian organizations, in 1993, 15,000 Palestinians were being held in civil and military prisons detention centers.

Twelve Palestinians have died in Israeli prisons since the beginning of the intifada, some under circumstances which, according to Betselem, have not yet been clarified. This humanitarian organization also indicates that at least 20,000 detainees are tortured every year during interrogation in the military detention centers.

Le Monde, September 12, 1993

So many violations of international law, treated like a “worthless scrap of paper” – all the more so, as Professor Israel Shahak writes:

… because these settlements, by their very nature, partake of a system of plunder, discrimination and apartheid.

Shahak, Racisme, p. 263

Here is Professor Israel Shahak’s testimony on the idolatry which consists of replacing the God of Israel with the State of Israel:

I am Jew who lives in Israel. I consider myself a law-abiding citizen. I do my time in the army every year even though I am over forty years old. But I am not “devoted” to the State of Israel or any other state or organization! I am attached to my ideals. I believe that one must tell the truth and do what is necessary to preserve justice and equality for all. I am attached to the Hebrew language and poetry, and I like to think that I modestly respect some of the values of our ancient prophets.

But make a cult of the State? I can well imagine Amos or Isaiah if they had been asked to make a cult of the kingdom of Israel or Judea!

Jews believe, and repeat three times a day, that a Jew must be devoted to God and to God alone: “You will love Yahweh, your God, with all your heart, with all your soul and with all your might” (Deuteronomy 6:5). A small minority still believes in this. But it seems to me that most people have lost their God and replaced Him with an idol, as when they worshipped the golden calf in the desert so much that they gave up all their gold to make a statue of it. The name of their modern idol is the State of Israel.

Shahak, Racisme, p. 93

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 18, no. 5/6 (September/December 1999), pp. 38-46

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: n/a