The Three Photographs of an Alleged Gas Van

Between 1945 and 2012, the entire literature about the gas vans has presented exactly three photographs which allegedly show such vehicles. Sometimes it was explicitly claimed that the vehicle had been used for homicidal purposes, sometimes this was implied. In 1994, these photographs were subjected to a critical analysis by Udo Walendy[1] and Pierre Marais.[2] In 2011, Santiago Alvarez, who expanded and improved Marais’s study, once again addressed the problem of the gas van photographs.[3] The author of the present article has – independently – researched the gas van issue for several years and would like to discuss here some additional aspects.

1. Simon Wiesenthal’s Gas Van

In 1963, Der Spiegel first published the photograph of an alleged gas van “camouflaged” as a Red Cross vehicle. In the course of the following 25 years, Der Spiegel recycled this picture four times[4] without ever mentioning its source (Fig. 1). We cannot but conclude that – except for the two other photographs which will be analyzed soon – the politically correct German news magazine did not have any further pictures of a gas van and was unable, or unwilling, to disclose the origin of the photograph.

Source: Der Spiegel (51/1968)

This alleged “Gas Van camouflaged as a Red Cross vehicle” appears rather fuzzy; the view is strictly from the rear, without any perspective. Except for the non-identifiable human figure in the background, no details of the surroundings are discernible. The ground as well as the back of the van seem to have been painted with spray. In all likelihood, this is a drawing rather than a photograph.

On 31 May 1973, during a campaign for the extradition of the “gas van murderer” Walther Rauff from Chile, “Nazi hunter” Simon Wiesenthal presented said picture at the Hebrew Union College in New York.

As Wiesenthal delivered his speech to a friendly audience, it is improbable that he was bothered with probing questions about the origin of the picture. The picture reminds the drawing of an architect or an engineer, and “Engineer Wiesenthal” (as he liked to call himself, in line with Austrian tradition) had earlier drawn pictures of atrocities allegedly perpetrated in German concentration camps.[5] It is therefore legitimate to suspect that this picture was fabricated by Wiesenthal himself. To the best of our knowledge, he never claimed having personally seen such a vehicle. Probably it was Wiesenthal who provided Der Spiegel with a copy of this picture in 1963. As we already mentioned, the German news magazine published it no fewer than five times, always insinuating that this was an authentic photograph of a vehicle in which human beings were killed with poison gas.

In 1983, when yet another campaign for the extradition of Walther Rauff from Chile was being waged, Simon Wiesenthal once again confronted the press with pictures of Rauff, and of the gas van.

In recent years the picture of the “Red Cross Van” has almost fallen into obscurity. In this context it bears mentioning that the politically correct authors of the Website “Action Reinhard Camps” have published an article containing some pictures of large trucks with cubicles,[6] adding that the German gas vans could have looked more or less like this. The authors candidly admit that these pictures are “no originals”, and they tacitly refrain from publishing Wiesenthal’s “Red Cross Van”.

2. The “Gas Van” of Kulmhof (Chelmno)

In 1981 Der Spiegel once again presented an alleged photograph of a “gas van,[7] a large truck with a big enclosed cargo space manufactured by the firm Magirus Deutz (Fig. 2). The left engine hood and the left front wheel are visibly heavily damaged. The vehicle is being inspected by two civilians; the third man wears a non-identifiable uniform.[8] This photograph seems to be genuine but does not prove anything.

By original uploader in the Russian Wikipedia was Zac Allan, and then Jaro.p [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Originally from the archives of the Polish Ministry of Justice. Sign. No. 47398

”Gassing van by which in the extermination camp of Chelmno (Kulmhof) and in Konitz Jewish people were annihilated (Archive of the Polish Ministry of Justice).”

In 1994, revisionist historian Udo Walendy published a low-quality reproduction of this picture (the only one at his disposal) in his analysis of “forged photographs.” Walendy pointed out that virtually nothing was known about the origin of the photograph and that there is no technical description or expert report about the alleged gas vans. It may have been a coincidence, but only a year later (1995) Jerzy Halbersztadt, a historian from Warsaw University who then worked at the US Holocaust Museum in Washington, threw light on the origin of this picture. The impetus for his research was not provided by Walendy’s publication (as Walendy is a revisionist, Halbersztadt predictably chose to ignore him) but by Leon Zamosz, a Holocaust historian of Polish-Jewish descent and a founding member of the USHMM, who had been “trying to find a photograph or any other graphic illustration of the gas vans used at Chelmno and other places” and had sent a circular letter to various Holocaust experts ( “multiple recipients of list HOLOCAUST”).[11] A few weeks later, in October 1995, Halbersztadt communicated the results of his research to the addressees of the “List HOLOCAUST.”[12]

During the same period, German revisionist historian Ingrid Weckert, who was then studying the alleged extermination camp Chelmno, asked Yad Vashem about the origin of this picture; however, the Israeli memorial was unable to answer her question.[13] In 1999, Ingrid Weckert published an article about Chelmno,[14] which may or may not have prompted Halbersztadt to publish the e-mail correspondence between himself, Zamosz and the List HOLOCAUST in 2005. This step was obviously taken in mutual agreement with the aforementioned ARC Team, a circle of amateur historians who focus on the history of the Action Reinhard Camps. Apparently, the ARC Team wanted to present an up-to-date view of the “extermination camps” and the “gas vans”, which implied some cautious revisions of the traditional picture of the events, as “evidence” which had turned out to be untenable was jettisoned. We already pointed out that Wiesenthal’s picture of a “gas van” camouflaged as a Red Cross vehicle was not presented by the ARC people. The damaged truck of Kolo (Fig. 4) was equally absolved from the suspicion of having served as a gas van: On its website, the ARC team published the aforementioned e-mail correspondence, but without any comment. There was only a short remark, that the photo of the KHD wreck of Kolo could “possibly not show a gas van.” Most readers presumably failed to appreciate the significance of Halbersztadt’s research.

The Result

The main source of the following account is Halbersztadt. His article is largely based on the report of a Polish Public Prosecutor’s Office which had investigated the matter in 1945. In all likelihood, the protocol of inspection drawn up by the Polish authorities was also translated and published by Halbersztadt.[15] According to this account, the alleged “gas van” had been a furniture truck used by a moving company in Thuringia. Later this vehicle was confiscated and probably used for disinfecting or delousing textiles in the Warthegau (a part of Poland annexed by Germany in 1939). Probably due to a traffic accident, the engine of the van was so badly damaged that the vehicle could not be repaired under the prevailing circumstances. After the still-usable parts had been removed, the wreck was left behind on the property of the former Polish firm Ostrowski, which had served as office of the Reichsstrassenbauamt (Reich office for road construction) Warthbrücken (the German name for Kolo).

Only 12 km from Kolo, near the hamlet of Chelmno (which the Germans called Kulmhof), the German occupying authorities had set up a transit camp for the Jewish population of the area. According to the victors’ version of the events, Chelmno was the first “extermination camp” where Jews were systematically murdered with gas. Traditional historiography has it that three or four gas vans were used at Chelmno. Occasionally these vehicles were allegedly repaired at the Reichsstrassenbauamt Warthbrücken, where several Poles who said they were mechanics who were employed there claimed to have seen them.

In May 1945, the “Main Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland”, which was founded after the German retreat, started its activities at Chelmno/Kulmhof. The Commission interrogated Polish witnesses from this region who, thanks to their critical technical skills, had been allowed to stay in the Warthegau after its annexation by Germany and had worked there during the war. In October 1945 the wreck of the truck left on the property of the Reichsstrassenbauamt was subject to a thorough scrutiny whereupon the Commission set up a protocol of inspection and shot four pictures that finally ended up in the archives of the Commission together with the protocols of the interrogations of the witnesses.[16] Only in 1995 was this important historical material unearthed by Halbersztadt’s collaborator Marek Jannasz, but the historians would have to wait for another ten years until it was finally made accessible to them.

It is of paramount importance to distinguish clearly between the alleged “gas vans of Chelmno” (of which no trace has ever been found) and the wreck of the furniture van the photograph of which was for decades presented as evidence of the existence of gas vans. Jerzy Halbersztadt extensively quotes from the protocols of interrogation of the three Polish car mechanics Jozef Piaskowski, Bronislaw Mankowski and Bronislaw Falborski, who said they had been employed by the Reichsstrassenbauamt and claimed to have personally seen the gas vans several times. Their statements seem to corroborate the criminal function ascribed to these vehicles. If we are to follow these three witnesses, the exhaust pipe of the van had been modified, and the floor of the load compartment had an opening through which the exhaust gas could be led into the load compartment. Several revisionist researchers (Ingrid Weckert, Carlo Mattogno, Pierre Marais and Santiago Alvarez) have pointed out extensive incongruities and contradictions in these descriptions of the alleged killing technique. However, we will not dwell on this aspect of the question but return to the damaged van instead. In this context the following three facts are crucially important:

- All Polish witnesses declared that the three (or four) gas vans of Chelmno had been black (“All of them were black”). But the photograph of the vehicle unmistakebly shows that it was not black, but much brighter; according to the protocol of inspection, it was “grey-green”.

- We should be able to assume that the Polish investigators carefully examined the van in order to ascertain if the exhaust had been modified for criminal purposes and if the load compartment had an opening for the exhaust gas. Quite obviously this was not the case, as this fundamental point was not even mentioned in the protocol.

- Not a single witness identified the damaged truck with the “gas vans of Chelmno”.

All these arguments were taken up by Jerzy Halbersztadt, who writes14: “The inspection of the van in Ostrowski factory, done on 13 November 1945 by the judge J. Bronowski, did not confirm the existence of any elements of system of gassing of the van’s closed platform.”

The negative conclusion (no modified exhaust pipe, no opening for the exhaust gas) was not mentioned in the protocol of inspection. This omission clearly reflects the political atmosphere prevailing at the time: Despite the negative results of the investigation, the Poles obviously wanted to use the wreck for propaganda purposes, and the four photographs were provided with the caption “Van used at Chelmno for killing people by means of exhaust gas”. This was the origin of a historical lie. Through Gerald Fleming’s book11 , this lie found its way into the literature about the “gas vans” and was recycled for decades. Until 1950, former Polish resistance fighters wanted the wreck to be taken to the memorial of Auschwitz or Majdanek (at that time there still was no memorial at Chelmno), but their suggestion was rejected. Finally, the vehicle was apparently scrapped (Halbersztadt). Halbersztadt himself makes a rather feeble attempt to argue for a possible criminal use of the truck; he writes:[15]

“I cite all these details to make possible the further comments to the story of this van. It is my feeling that there are some unclear points in this story. Nobody explained for what purpose this van was used? Its door was tightened with an impregnated canvas.[17] What for? Some witnesses had seen this car in the area of the forest of Chelmno starting from the spring of 1942. It is possible that it belonged to the SS-Sonderkommando Kulmhof, too. I came across a version that this van was used for a disinfection of victims’ clothes but there are no grounds for it.”

Although Halbersztadt deplores the fact that function of the vehicle remains unknown, he volunteers the information that it was purportedly used “for a disinfection of victims’ clothes”. Whether the owners of these clothes were really “victims” is an open question; however, there can be no doubt whatsoever that the van was indeed used for disinfection. Two of the pictures shot by the Polish commission show remnants of wooden frames within the cubicle. It is highly probable that they were used for hanging up garments (Fig. 3).

Photographs: Polish Commission, 1945. Public Domain.

Apparently, the Polish commission that inspected the van in October 1945 endorsed the view that it had been used for disinfection purposes because they chose the following title for their inspection protocol:

“Inspection of the former Wehrmacht disinfection van used at Chelmno death camp in 1941-42.”

The protocol ends with the following sentence: “With this, the inspection was concluded.” Any further comment seems superfluous, but we will keep in mind that the Polish authorities knew since 1945 that the KHD furniture truck in question had been no “gas van.” In spite of that, the photos received a false caption, and with Fleming’s book this lie went around the world.

3. Saul Friedländer’s photomontage

In 1966 Der Spiegel published the photograph of a “SS gassing van”. By no stretch of the imagination is it possible to discern more than the back part of an automobile from which hoses lead into a wall (Fig. 4).

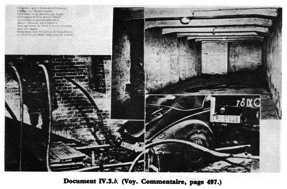

In the French original of Friedländer’s book the caption (Fig. 5, above left) translates as follows:

“The gas chamber at Belzec, which was called ‘Heckenholt-Stiftung’. The prisoners were killed within 32 minutes by the exhaust gas of a Diesel engine. Gerstein, who had assisted at this action, describes the procedure in his report. Heckenholt was the [illegible] of the facility and the one who started the engine.”

Friedländer wants his readers to visualize the horrible gassing scene at Belzec described by SS-Obersturmführer (First Lieutenant) Kurt Gerstein. But Gerstein had asserted that a big Diesel engine had been used to produce the necessary exhaust gas. Instead of such an engine, we see the front part of a car and the back of a truck of which little more than the license plate is discernible. From both vehicles, hoses lead into a wall. In other words: Instead of Gerstein’s Diesel engine, the engines of these two vehicles serve as (stationary) producers of exhaust gas. The vehicles are thus no “gas vans” where the exhaust gas was blown into a portion of the vehicle. As a matter of fact, unlike Der Spiegel, Friedländer does not speak of a “gassing van”. Apparently, he only wanted to illustrate the “gas chamber of Belzec.”

But there is yet another incongruity: On the left side one sees the wall of a building, allegedly the wall of the “gas chamber of Belzec”. Logically one would suppose that the picture on the right side shows the interior of this same gas chamber, but as a matter of fact it shows the morgue of Crematorium I at Auschwitz I (Main Camp), which is still presented as a homicidal gas chamber to the tourists. Publishing this photograph in the context of Belzec without any comment is a fraud and an attempt to deceive the reader. We now know that the objects visible on the photograph have nothing to do with Belzec: They illustrate an event which transpired in Mogilev, Belarus, in September 1941.

The “gassing experiment” of Mogilev

The following can only be understood by considering the situation that the German authorities had to face at the time. During the retreat of the Red Army in the summer and fall of 1941, the Soviets performed an impressive logistical feat, evacuating the most vital industrial plants as well as the cattle and the food stocks to the east. As far as the population was concerned, those evacuated were essential specialists and functionaries. Facing the German advance, the Soviets resorted to the strategy of “scorched earth”, without any consideration for the civilian population left behind, which was thus deprived of its basis of existence.

At the same time (fall 1941), the “euthanasia” actions had already been carried out in Germany as well as in some occupied countries such as Poland and the Baltic states. It appears that the German authorities (Hitler, Himmler) had decided to extend the euthanasia also to the occupied Soviet territories, and their decision was certainly assisted by the fact that the mental hospitals in Russia had partly been left without food supplies, and some of the staff had fled. Himmler was obviously not willing to cater for Soviet mental patients. Thus, the Einsatzgruppen of the SiPO (Sicherheitspolizei) and the SD (Sicherheitsdienst) were, additionally to their main task of fighting the partisans, assigned with a further task: to dispose of the mentally ill. For the respective German task forces (Einsatzgruppen) this meant a considerable psychological stress, because they had to conduct the executions. Himmler, who had observed on his visit in Minsk (15 Aug. 1941) a mass execution of partisans, had come to the conviction, too, that a more humane method of killing was desirable. He talked about that matter with two of his Generals, Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski[20] and Arthur Nebe.[21] Himmler assigned Nebe to examine the issue of painless killing and send him a report. Nebe obviously shared Himmler’s opinion, and reportedly he stated: “I cannot possibly ask German soldiers to shoot the mentally ill!”

In Germany, the killing operations of “euthanasia” had been carried out by means of carbon monoxide (CO), however, this gas was not available in Russia, at least not in the usual gas cylinders. Transporting them from Germany to Russia (and the return of empties) would have been impractical under the prevailing circumstances. In this situation, it appears that Nebe (Fig. 6) had thought about two “alternative” killing methods: a) by explosives and b) by exhaust gas. It was apparently an “isolated decision”, for nothing is known of any discussion, neither with his entourage in Minsk nor his chemical experts in Berlin.[22] This lack of consultation and advice can be explained by the circumstances: the distance between Nebes’s quarters in Smolensk and his experts in Berlin, and security reasons. Oddly enough it did not occur to him that the wood-gas generators, which were extensively used in Germany, would have constituted an available mobile source of CO. Most probably the chemists of the KTI would have opted for this solution, although certain modifications of the wood-gas generator might have been necessary and would have caused a delay – and Nebe had to act under pressure of time.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101III-Alber-096-34 / Alber, Kurt / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons

In connection with the gas-van photos only the Mogilev event is of concern here. Some days after the experiment in Minsk Nebe and Widmann met in Mogilev and visited an asylum, where Nebe had already prepared the Russian doctors. A room on the ground floor of the building was chosen, and the only window was closed with masonry, which had openings for two metal pipes. Outside, each pipe could be connected with a metal hose coming from the exhaust of an automobile. After at least five mental patients had been placed in the room, the exhaust gases of one car were led into the room. When after 5 minutes the people were still alive, a second vehicle was connected to the room – this time a truck. It lasted then about 8 minutes until all the test persons were dead. The room was opened only after 2 hours.

The Origin of the Photomontage

In 1961, when the first witness testimonies about Mogilev became available, four photographs were submitted to the Central Agency for the Prosecution of NS crimes at Ludwigsburg. According to a letter of the Public Prosecutor’s Office Stuttgart,[24] these photographs showed “a gassing operation (two hoses are connected both to the exhaust pipes of two vehicles and a walled room)”. The Senior Public Prosecutor considered these photographs important enough to inform the General Public Prosecutor and the Ministry of Justice of their existence:

“As this gassing operation is probably identical with the one carried out at Mogilev by Nebe and the defendant Dr. Widmann, further investigation as to the origin of the photograph and the former owners of the vehicles discernible on the same have become necessary.”

Where the Central Office had obtained the four photographs from, and what results the “further investigation as to the origin of the photograph” yielded, is unfortunately not indicated in the files. The single surviving letter about this matter runs as follows:[25]

“As to the photographs contained in the files which show the introduction of exhaust gas from a truck and an automobile into a walled room, further investigations have been carried out. They lead to the conclusion that the truck with the license plate Pol 51628 belonged to the Police Battalion 3 and that the driver of this truck was most probably Gerhard R[…] from Stettin who was killed in action in the district of Traunstein on 3 May 1945.”

The tag number “Pol 51628” mentioned in this letter matches the licence plate of the truck on Friedländer’s photomontage. Furthermore, the two vehicles visible on the photograph seem to corroborate eyewitness accounts according to which an automobile of the brand “Adler” and a police truck had been used. So, in order to illustrate the “gas chamber of Belzec,” Friedländer availed himself of the very same photograph which had been submitted to the German justice as evidence for the Mogilev killing in 1961. This proves that his photomontage is a complete forgery.

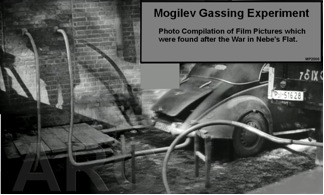

A reasonably good reproduction of the Mogilev photo was published on the Website of the aforementioned ARC Team (Fig. 7).

The Photograph of “Mogilev”

i. Was it Really Possible to Take Pictures or Shoot Films at Mogilev?

Since the pictures were taken at close range, the photographer must have been authorized to document the scene. On the other hand, there can be no doubt that taking pictures of a secret operation was strictly forbidden. None of the witnesses mentioned anybody taking photographs, much less shooting films. When confronted with the pictures, the defendant Widmann explicitly stated that he had observed no such activities.

The expression used in the caption – “Film Picture” – means a still photo from a movie picture, and indeed the photograph (Fig. 7) has certainly been made by professionals (note the scene lighting!). On the other hand, the idea that a film team should have been invited to immortalize such secret actions is risible from the outset. Thus, we may safely conclude that this photograph was produced by unknown people at an unknown time, but certainly well after the event it purportedly shows. Presenting it as an authentic document is therefore nothing but a deliberate act of forgery.

ii. The Shadow on the Wall

The picture was obviously shot in the beam of a stage light, i.e. in the evening or at night. On the wall of the house, an ominous and highly symbolic shadow of a human figure can be seen – the SS man! Apparently, the unknown photographer did his best to create this shadow, as the person who casts it is not visible. This feat certainly required professional lighting. In other words, this forgery is the work of professionals. It definitely does not show the Mogilev test gassing, because according to the defendant Dr. Widmann, the action took place in the morning or forenoon:[27] “The action was carried out in the following morning.” The different time zones (Mogilev lies on the 30th meridian eastern longitude) is irrelevant in this context. It is quite true that German time (Central European time) was used throughout the occupied Soviet territories (which meant that in the Caucasus – to mention but one example – dusk came on as early as two o’clock), but as the action commenced in the morning, this merely meant that the sun was already standing a bit higher than in Germany.

iii. The Official License Plate of the Truck

Even if the license plate “Pol 51628” actually existed, this does not prove the authenticity of the picture. After the end of the war, the Allies confiscated tons of German documents; nothing speaks against the possibility that they found a list of the license plates of Police Battalion 3.

iv. The Alleged Discovery of the Picture “in Nebe’s Flat”

According to the caption, the photograph was found in Nebe’s apartment after the war. This information is volunteered by British-Jewish Holocaust historian Gerald Reitlinger in the first English edition of his standard work[28] (Chapter 6, p. 130, unnumbered footnote). In his description of Himmler’s visit in Minsk, Reitlinger states:[29]

“This story of von dem Bach-Zelewski’s finds some confirmation in the discovery in 1949 in Nebe’s former Berlin apartment of an amateur film, showing a gas chamber operated by the exhausts of a car and a lorry.”

By way of a footnote in the footnote,[30] Reitlinger finally manages to reveal the source of this information, a letter addressed to him, together with some photographs, by “Mr. Joseph Zigman, Information Services Division, Office of the US High Commissioner, Germany”. He does not disclose the date of the letter. We have found this reference to Reitlinger in an article by German Holocaust historian Mathias Beer.[31] Even to Beer, the idea that the euthanasia action at Mogilev should have been filmed seemed apparently so outlandish that instead of an “amateur film” he prefers speaking of “negatives” – a minor cosmetic change meant to make the improbable a trifle less improbable.

The legend of this discovery justifies a short digression. Arthur Nebe was involved in the abortive coup of 20 July 1944. After the failed attempt on Hitler’s life, he managed to go underground. In early 1945, he was denounced and arrested; on 2 March, 1945 he was sentenced to death by the Volksgerichtshof and executed shortly afterwards. It is all but certain that the Gestapo thoroughly searched his house after the events of 20 July 1944, and they would surely have found and confiscated the film, had Nebe indeed kept it at home. The alleged search of his “apartment” after the war is a highly fishy story, as he owned a house and did not live in an apartment. Theoretically, the search could have been effected at the apartment of his widow, but there is no evidence to back up this theory. To cut a long story short, the legend of the “discovery of the Mogilev photographs” is every bit as phony as the picture itself.

We do not know if the “Mogilev” photographs were indeed unearthed in 1949, as Reitlinger’s source Zigman claims, or when they really were fabricated. At any rate, they existed in November 1952, when Reitlinger published his book. And that raises another question: How did the anonymous fabricators know (in 1949) what had happened in Mogilev? The Mogilev case and even Arthur Nebe had not been mentioned in Nuremberg, and the investigations against Dr. Widmann did not begin before 1959. Thus, they knew probably only the story of von dem Bach-Zelewski and – perhaps – the statements of the Russian doctors from the Mogilev asylum. Neither of them had been a direct eyewitness, and therefore the fabricators did not know certain details.

v. How Did the German Legal Authorities Get Hold of the Photographs?

Starting in 1959, several investigations were initiated against former members of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Dr. Becker, Pradel, Schmidt, Dr. Widmann etc.) who were accused of having taken part in the euthanasia action or in the development of the alleged gas vans. As a general rule, the statements of defendants and witnesses in a pending case are not made accessible to the public. However, at least in the case of Mogilev there is ample reason to suspect that the preliminary results of the investigation were passed on to Israeli historians as early as 1960. Both sides communicated on friendly terms (“Lieber Shmuel” [Krakowski]).

When witness accounts about the murky events of Mogilev in September 1941 began to filter to Israel, certain people may have been reminded of the photographs which had been fabricated 1949 as “evidence”. Apparently, they could not resist the temptation to make renewed use of these forgeries and passed them on to the German authorities. To their credit, the German public prosecutors were prudent enough to consider “further investigation about the origin of the photograph necessary”, and the pictures were not used as evidence at the trial.

vi. The Inserted Caption

Although the inserted caption of the alleged Mogilev photograph (Fig. 7) seems very official and thus credible, it is rather unusual in a photographic document. Anyone who covers or removes parts of a document risks being accused of foul play. On the other hand, the caption is in English and obviously could have been inserted only after the war. So, what was the intended purpose of this caption?

The fabricators were well aware that most observers would be unable to interpret the photograph and needed to be enlightened by means of a caption. For Saul Friedländer, who was looking for photographic material about Belzec, this posed of course a problem, as the caption unmistakably reads “Mogilev Gassing Experiment” (Fig. 7). Undoubtedly for this reason, he covered the upper right part of the photograph with a picture of the alleged Auschwitz gas chamber, thus creating a classic photomontage. When Der Spiegel published the forged photograph of Mogilev (Fig. 4), it resorted to yet another forgery, manipulating the picture in order to present it as an “SS gassing van”. The forgers simply cut off the right half of the picture, and the still-visible part of the inserted caption was retouched and transformed into the grey wall of a house, making the upper part of the car disappear as well.

Eyewitness accounts about Mogilev

At the beginning of the German investigations of 1959/60 the two main defendants were still available: Dr. Albert Widmann and his laboratory assistant Hans Schmidt who had accompanied him to Belarus. What did they have to say about the pictures? During his interrogation, Schmidt was shown the four photographs showing “a building and vehicles.”[32] While identifying an automobile of the brand “Adler”, he objected:

“In my opinion these pictures were not taken during the action in Mogilev. I only remember a connecting piece and a hose. I also believe that the boards lying before the wall and the post which can be seen on the picture did not exist at Mogilev. Furthermore, I remember that only the window was walled up with bricks and that the rest of the building was not made of bricks. Finally, I think that in Mogilev the vehicle stood further away from the house and that the position of the connecting piece [in the wall of the house] was lower. The license plates of the vehicles visible in the picture are unknown to me, this means that I do not know these license plates. […]

My memory of the action in Mogilev strongly differs from the scenes in these pictures. Therefore, I think that these pictures do not show the action in Mogilev. The facility shown on the photographs seems to be quite sophisticated whereas the facilty used at the action in Mogilev was clearly provisional.“

During another interrogation of Schmidt,[33] the investigators wanted to know which driver had driven the “Adler” close to the wall of the house, so that the metal hose from the exhaust pipe could be attached to the connecting piece in the wall. This question was a delicate one as it directly touched upon the problem of responsibility (participation in a crime). Schmidt remembered that the “Adler” had been backed up to the connecting piece; however, the vehicles on the alleged Mogilev photographs are standing parallel to the wall of the house.

Before being shown the pictures, and before knowing what his interrogators had in mind, the defendant Widmann stated that the building where the gassing had taken place had been “neither a wooden house nor a building made of brick” but “covered with white plaster”. When he was confronted with the pictures, he made the following statement:[34]

“The scene shown on this picture cannot show the events at Mogilev. As I already made clear, the building was covered with white plaster and had a foundation block. Moreover, one of the two hoses we had brought with us was much thicker than the other one. The vehicles used at Mogilev did not stand parallel to, but perpendicular to, the wall of the house. To the best of my remembrance, the hose did not have a support. I am unable to identify the vehicles in the picture as vehicles of the RKPA [Reichspolizeiamt]. The RKPA did not have any trucks at all. I do not know the license plates of the vehicles, in particular, I cannot explain the tactical sign on the platform of the truck. I do not know this sign.

After a second look at the pictures, I wish to point out that the window walled up with bricks sharply stood out against the wall of the house, which was covered with white plaster, and looked abominably ugly. Finally I did not see anybody taking pictures.”

Apparently the statements of Schmidt and Dr. Widmann, which were made independently of each other and basically agreed, convinced the Public Prosecutors, so they refrained from using the photographs as evidence in the trial. This deals the final blow to this photograph (Fig. 9) as well.

Certain circles who had studied the Soviet reports from the first post-war years may have felt the desire to belatedly illustrate some scenes in order to fabricate propaganda material against the “fascists.” Probably the sinister event which had taken place at Mogilev was “reconstructed” in this way. However, a “reconstructed picture claiming to be authentic is universally regarded as a forgery. Except for a short mention in Reitlinger’s book the pictures were initially not used for propagandistic purposes. But during the preliminary investigation against Dr. Widmann, when the topic “Mogilev was placed in the limelight, these pictures were rescued from oblivion und passed on to the German legal authorities. Der Spiegel seems to have been the first to publish one of the Mogilev “gas van pictures”, and a few months later Saul Friedländer followed suit.

4. Conclusion

In the entire literature of German war crimes, we find only three photographs which claim to show one of the alleged “gas vans”. None of them is serious evidence for this pretension; each one is – in one sense or the other – a fake.

Simon Wiesenthal’s “gas van camouflaged as a Red Cross vehicle” is obviously a drawing and not a photograph. Even the politically correct ARC Team refrained from recycling it in an article in which different big vehicles were shown to depict how a gas van could have looked (whilst the authors conceded that their pictures were “not authentic”). Maybe Wiesenthal has not pretended expressis verbis that his picture was evidence, but it was at least a “tacit insinuation” – making people believe something without saying it explicitly.

The “Chelmno gas van” which had been originally a furniture truck and later used for disinfection of clothing was examined and correctly identified by a Polish commission as early as 1945. The Polish experts found no evidence whatsoever that it had served for homicidal purposes. Nevertheless, the Polish authorities provided the authentic photos with a false caption, identifying the vehicle as a “gas van”. Here we have the case that, although the photograph is authentic, it becomes due to the false caption a deliberate forgery.

Although the photograph of the “gassing experiment at Mogilev” purports to be authentic, this cannot be true since on that September day in 1941, there was certainly no film team present, and photographing was strictly forbidden. Obviously, we have here a re-enacted scene produced by professionals (floodlight!). Re-enacting historical scenes is quite usual in the film and TV industry, but if such a photo claims to be authentic it becomes a forgery. With the Mogilev photo we can only presume that it was taken around 1949. The first attempt to use this material was made by passing it on to the German justice (1961). The attempt failed since the judicial authorities were suspicious.

Then the news magazine SPIEGEL made use of the “Mogilev photo”. The SPIEGEL people may have recognized that the caption “Mogilev Gassing Experiment” which is inserted into the picture (Fig. 9) did not suit a historical photo and removed the caption by retouching. Thus, a forgery was manipulated again to make it more credible. And then there was Saul Friedländer who sought an illustration for the (alleged) gas chamber of Belzec. He also could not use the caption and removed it, this time by cutting it away and filling the gap with another photo, thus creating a photomontage, which he finally used to illustrate a scene which (allegedly) had taken place at quite another location (Belzec instead of Mogilev). How Der Spiegel and Saul Friedländer got hold of one of these pictures remains unknown.

The fact that three dubious pictures were used for propaganda purposes throws light on the attempts of certain circles to corroborate the gas van story with photographs, even forged ones. Of course, the absence of authentic pictures does not prove the non-existence of gas vans. For this reason, the question whether such murderous vehicles indeed existed can only be answered on the basis of other material (documents, eyewitness reports etc.). However, the manipulations some people resorted to in order to “prove” the existence of the gas vans with fraudulent means should give pause to those tempted to credit the allegations.

Addendum

The above article had just been closed when the editors of Inconvenient History discovered an interesting fact: The American documentary film “Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today” (USA 1947).[35] In reel 5 of this film,[36] there are two short sequences (in total no longer than 33 seconds) which were used (amongst others) to accompany a speech of Soviet Main Prosecutor Gen. Rudenko in Nuremberg.

One of the sequences (it is no more than a pan shot) shows clearly a sinister scene of the Mogilev gassing experiment with the car and the truck standing before a house wall and the shadow of a person in military boots. An engine is roaring at full throttle. Here we have the source of the photo which allegedly had been found “in Nebe’s flat in 1949”, published by Reitlinger in 1952, later presented to the German investigators against Dr. Widmann (ca. 1960), and still later by Der Spiegel (1966) and Friedländer (1967).

The second film sequence is split into two parts: First we see five male patients – dressed in white hospital garments – passing the camera seated on a horse cart. Then we see a horse cart halting before a building, one man and two children have got out, whilst another man is still lying on the cart (Fig. 8).

Since the patients are emaciated and weak they are helped by a male and a female doctor or orderly, and those who are naked are given blankets. In the background a German soldier is watching. The white hospital garments of the patients, the white lab coats of the sanitary personnel and the horse cart indicate that the scene is somewhere in Russia, and since the “arrival sequence” is intermingled with the “car sequence” it is clear that both pertain (allegedly) to Mogilev.

If the two sequences are authentic, they can stem of course only from the Germans. Consequently, the German Fritz-Bauer-Institut,[37] which compiled a description of “Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today”, ascribe the origin of the sequences to “Deutschland, 1941”. And the USHMM writes:[38]

“USHMM Details from Dr. Albert Widmann’s 1967 trial in Stuttgart include his personal description of actions corresponding to the scene of gassing by vehicle exhaust, in the company of Arthur Nebe, and the presence of one male Soviet doctor and two female Soviet doctors (in German-occupied territory in the vicinity of Mogilev, Belarus, mid-September 1941).”

To this we respond: Although the pictures seem to be consistent with Mogilev, they conflict with several of even the few details available to us. Indeed, the gassing experiment was conducted in one of the buildings of the asylum and the victims, who came from other buildings, were brought by horse carts. But: The building had – according to Widmann – white walls and not brick walls, and the crude wooden door suits rather a horse barn than the entrance into a hospital or asylum. The presence of children amongst the patients was not mentioned neither in Mogilev nor in Minsk. Whether Widmann has stated that Russian doctors were present during the gassing experiment, as the USHMM claims without giving a source, is not certain. Finally, Widmann has clearly stated that he had not seen anybody photographing in Mogilev (much less a film crew). From the German point of view any photo documentation would have made no sense, in direct contravention of the necessary secrecy.

Therefore, the Fritz-Bauer-Institut is wrong in their attribution “Germany, 1941”. The pictures are re-enacted and therefore fake. Who were the real producers? To ask this question means to answer it: The Mogilev event was a Soviet issue, and the pictures reveal that the fabricators must have known some details but overlooked others. The Mogilev event had not been dealt with in Nuremberg, and the investigation against Widmann started only in 1959. So, how could the Soviet propagandists know what had happened in Mogilev? The town was reconquered by the Red Army on 28 June 1944. Thus, the ESC (Extraordinary State Commission) had time enough to interrogate the Russian doctors of the former asylum, to learn details of the gassing experiment (as far as the doctors knew), to produce the film sequences and – to forward them to OMGUS.

One of the OMGUS men was, by the way, Joseph Zigman, who – together with Stuart Schulberg, was the creator of “Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today”. After the film was completed in 1947/48, “Zigman stayed on in Berlin to edit de-Nazification and re-education films aimed at German audiences under the aegis of the U.S. Military Government’s Documentary Film Unit, which was headed by Stuart Schulberg.”[39] It must have been at that time that Zigman forwarded one of the Mogilev photos to Gerald Reitlinger – together with the story that the “amateur film” had been found in Nebe’s flat. It is the hypothesis of this author (K.S.) that Zigman and Schulberg had received the two film sequences and the Nebe story from Soviet authorities in Berlin and deployed them, as it were, with a vengeance.

A further discovery of IH was a debate in the CODOH Forum[40] entitled “Carbon Oxide killings photos?”, which took place in 2005. The site presented some of the Mogilev pictures. Some of the participants knew the film “Nuremberg” and doubted the German origin of these pictures: “Turns out most of the time it ain’t even original footage but post-war propaganda stuff filmed in a way to look real. The viewer is not told, of course, and comes away with the impression he saw documentary footage.” (Participant “Grenadier”, Aug. 2005).

Concerning the Mogilev photos, great credulity is needed indeed to believe that these pictures are authentic.

Abbreviations

| ARC | Action Reinhard Camps |

| The “ARC Team” was a group of (amateur) historians who specialized in the “Aktion Reinhardt” camps and published the results of their research in the Internet. The last upload took place in 2006. | |

| HUC | Hebrew Union College (New York) |

| KHD | Klöckner-Humboldt-Deutz (Producer of Trucks) |

| KTI | Kriminaltechnisches Institut (Institute of Forensics) |

| RKPA | Reichskriminalpolizeiamt (Reich Criminal Investigation Department) |

| RSHA | Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Reich Security Head Office) |

Notes:

| [1] | Udo Walendy, Historische Tatsachen (HT), Verlag für Volkstum und Zeitgeschichtsforschung, No. 63 (1994), p. 34. |

| [2] | Pierre Marais, Les camions à gaz en question, Polémique, Paris 1994, chapter II.1. German Edition: Pierre Marais, Die Gaswagen – Eine kritische Untersuchung, Peter Hammer Verlag, Turin 2008. |

| [3] | Santiago Alvarez, Pierre Marais, The Gas Vans – A Critical Investigation, Barnes Review Holocaust Handbook Series, Vol. 26, The Barnes Review, Washington 2011. |

| [4] | Der Spiegel christened this vehicle alternately “Mobile Gas Chamber” (4/1963), “SS Gas Van” (21/1966), “NS Gas Van” (14/1967), “Gas Van of the SS” (51/1968) and “Rauff Gassing Van” (18/1988). |

| [5] | Simon Wiesenthal, KZ Mauthausen, Vienna 1946. |

| [6] | Website of the ARC Team, http://www.deathcamps.org/gas_chambers/gas_chambers_vans (August 2006). |

| [7] | Der Spiegel No. 35 (1981), p. 124. |

| [8] | On a reproduction showing a cropped section of the picture, shoulder straps and boots are discernible. The uniform is a Polish one. |

| [9] | Gerald Fleming, Hitler und die Endlösung, Wiesbaden, Munich, Limes Verlag 1982, p 128-129. |

| [10] | USHMM photo gallery, # 47398. |

| [11] | Leon Zamosz (professor of sociology at the University of California), e-mail of 25 August 1995 to the addressees of list HOLOCAUST; quoted according to ARC Team (Footnote 18). |

| [12] | Jerzy Halbersztadt (University of Warsaw and USHMM), e-Mail of 11 October 1995 to the addressees of List HOLOCAUST, quoted according to ARC Team (Footnote 18). |

| [13] | Letter of Yad Vashem to Ingrid Weckert of 16 March1988. |

| [14] | Ingrid Weckert,“Wie war das in Kulmhof/Chelmno? – Fragen zu einem umstrittenen Vernichtungslager”, Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung volume 3 no. 4 (December 1999), p. 425-437. |

| [15] | Protocol of Inspection by Judge J. Bronowski, Kolo, 13 October 1945 (a facsimile of the English translation can be found in the Internet). |

| [16] | Archive of the Main Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes in Poland, Warsaw, collection “Ob”, file 271 and others. |

| [17] | In Internet the author found an English translation of the Polish Inspection Protokol in facsimile (29.03.2009), where we read: “The doors are lined with tar paper” – which appears to be much nearer to the reality. |

| [18] | Der Spiegel, No. 53/1966, p. 57. The original source for this photo is a film compiled by Pare Lorentz and Stuart Schulberg. It was shown during the Nuremberg Trials and is identified as National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), 111 M 7596 R5. The film is in the Public Domain and may be found on-line at: http://resources.ushmm.org/film/display/detail.php?file_num=2151 |

| [19] | Saul Friedländer, Kurt Gerstein ou l’ambiguité du bien, ed. Casterman, Paris 1967; German version: Kurt Gerstein oder die Zwiespältigkeit des Guten, Bertelsmann Sachbuchverlag, Gütersloh 1968, p. 91-93. In the German edition, the photomontage of the “Belzec gas chamber” is absent. |

| [20] | SS-Obergruppenführer (General) Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski was Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer Rußland-Mitte (Higher Leader of SS and Police in Central Russia), stationed in Minsk. |

| [21] | Arthur Nebe was Reichskriminaldirektor and head of the RKPA (Reichskriminalpolizeiamt), which was a state office and simultaneously constituted Office V of the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt). After the beginning of the war against the Soviet Union, Nebe, who had the rank of an SS Brigadeführer and Lt. General of the Police, additionaly became the head of Einsatzgruppe B (Belarus), stationed in Smolensk. |

| [22] | Part of Nebes‘s Reichskriminalpolizeiamt (RKPA) was the Kriminaltechnische Institut (KTI). |

| [23] | Rüther et al., Justiz und NS-Verbrechen, Vol. XXVI, No. 658, Trial of Dr. Albert Widmann, Sentence of Landgericht Stuttgart of 15.09.1967 (Ks 19/62). |

| [24] | First Public Prosecutor Dr. Hillmann of LG Stuttgart, letter of 30 November 1961 to the Ministry of Justice of Baden-Württemberg. AZ 19 Js 328/60; in: Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg, EL 317 III, Bü 2152. |

| [25] | First Public Prosecutor Dr. Schneider, letter of 28 May 1963 to the First Criminal Chamber at the Regional Court Stuttgart. AZ 13 (19) Js 328/60; in: Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg, EL 317 III, Bü 2152. |

| [26] | ARC Team, Action Reinhard Camps/Gas Chambers Overview/Mogilev, in: http://www.deathcamps.org (January 2008) |

| [27] | Dr. Albert Widmann, interrogation at the Regional Court of Düsseldorf, 11 January 1960 (I 113/59). |

| [28] | Gerald Reitlinger, The Final Solution – The Attempt to Exterminate the Jews of Europe 1939-1945, Vallentine, Mitchel & Co., London 1953. First German edition: Die Endlösung. Hitlers Versuch der Ausrottung der Juden Europas 1939-1945, Colloquium Verlag, Berlin 1956, p. 144, footnote. |

| [29] | After the war Bach-Zelewski made depositions in U.S. captivity and was a witness in Nuremberg. His report of Himmler’s visit in Minsk and a talk with Nebe were partly printed in the German-Jewish paper Der Aufbau: E. M., “Leben eines SS-Generals, Aus den Nürnberger Geständnissen des Generals der Waffen-SS Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski,” in: Der Aufbau, New York, Jahrg. XII, No. 34, 23 August 1946, pp/ 2, 40; http://deposit.d-nb.de/online/exil/exil.htm.

Bach-Zelewski’s quotations do not – as Der Aufbau maintains – stem from his testimony in Nuremberg (7.1.1946), but from his former interrogations. His statements have to be considered critically since he – in order to save his head – may have “modified” some of his memories in the sense of the Allies. |

| [30] | Gerald Reitlinger, ibid (Engl. edition), chapter 6, endnote 22 (p. 552). |

| [31] | Mathias Beer, “Die Entwicklung der Gaswagen beim Mord an den Juden”, Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 35 Vol. 3 (1987), p. 403-417, footnote 36.

The footnote continues: “According to E. J. Else, dispatcher of the K unit [K-Staffel] of the first company, Police Battalion 3, the van which can be seen on one of the pictures belonged to his car fleet. Statement of 13.12.1962, StA Frankfurt a.M., Az. 4 Js 1928/60 [ZSL, Az. 202 AR-Z 152/1959, Bl. 1127]. Else was thus a member of Einsatzkommando 8, which took part in the experiment.” |

| [32] | Interrogation of Hans Schmidt by the Public Prosecutor’s Office at the Regional Court Stuttgart; in: BArch B 162/1604, p. 496-497 (archive page number). |

| [33] | Interrogation of Hans Schmidt by the Public Prosecutor’s Office Stuttgart; in: BArch B 162/1603, p. 473 (archive page number). |

| [34] | Interrogation of Dr. Albert Widmann in Düsseldorf, 18 April 1962; in: Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg, EL 48/2 I, Bü 319, p. 1303-1306 (archive page number). |

| [35] | Documentary Film “Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today”, Producer: Office of the Military Government in Germany, U.S. (OMGUS), USA 1947. Archives: National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Sign. 111 M 7596 R5. USHMM – Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive, Sign. RG-60.2416, Tape 67). Bundesarchiv/Filmarchiv in Berlin. |

| [36] | Reel 5 see http://resources.ushmm.org/film/display/detail.php?file_num=2151 |

| [37] | Fritz-Bauer-Institut (Frankfurt/Main) – Project Cinematography of the Holocaust, www.cine-holocaust.de/cgi-bin/gdq?dfw00fbw003511.gd |

| [38] | Film description of Reel 5 of “Nuremberg: …” (see endnote 1), short biography of Dr. Albert Widmann. |

| [39] | Website of Schulberg Production “Nuremberg” (www.nurembergfilm.org) |

| [40] | CODOH Forum, Committee for Open Debate of the Holocaust, http://forum.codoh.com/viewtopic.php?f=2&t=2418&p=16412&hilit=Carbon+Oxide+killings+ photos%3F#p16412 (Aug. 2005). |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 5(1) (2013)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a