“The Truth About the Gas Chambers”?

Historical Considerations relating to Shlomo Venezia's "Unique Testimony"

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- A Last minute witness

- The Title of the book

- The reasons for the silence

- The deportation to Auschwitz

- BIIa quarantine camp

- The first day in the “Sonderkommando”

- “Bunker 2”

- The first working day at the “Bunker” according to Venezia’s companions in misfortune

- The “cremation pits” in the vicinity of “Bunker 2”

- The recovery of human fat in the “cremation pits”

- The gas chamber in Crematorium III

- The transport of the bodies to the ovens of Crematorium III

- Crematory ovens and cremation

- The flaming chimneys

- The revolt of the “Sonderkommando”

- Salvation

- Epilogue

- Conclusion

1. A Long-after-the-Fact Witness

Shlomo Venezia, self-proclaimed ex-conscript of the so-called “Sonderkommando” of Birkenau, only decided to “speak out” in 1992. I discussed his testimony in 2002, in an article entitled “Another Last-Minute Witness: Shlomo Venezia.”[1] Few sources were available at the time. Venezia acquired a certain notoriety in 1995 thanks to an interview conducted by Fabio Iacomini, entitled “The Eyewitness Testimony of Salomone Venezia, Survivor of the Sonderkommando”;[2] his “Testimony at Santa Melania, 18 January 2001, the First Day of Memory” appeared six years later.[3] In January 2002, Venezia agreed to an interview with Stefano Lorenzetto,[4] republished, with a few minor changes, in the weekly magazine Gente in October 2002, under the title “I, a Jew, Cremated the Jews.”[5]

In my article mentioned above, I noted:[6]

“Shlomo Venezia, self-proclaimed conscript of the so-called ‘Sonderkommando’ of the Birkenau crematoria, remained, like Elisa Springer, silent for almost fifty years, but, in contrast to Springer, has not (yet) written his ‘memoirs.'”

As I anticipated, in 2007,Venezia finally filled the void, entrusting his memoirs to a book: Sonderkommando Auschwitz. The Truth about the Gas Chambers. A Unique Testimony,[7] which I shall examine from a historical point of view, including from the point of view of his prior statements.

2. The Reasons for the Silence

Before analyzing Venezia’s statements, it might be informative to examine the reasons that induced Venezia to keep silent “until 1992, 47 years after the Liberation”![8] Venezia himself has explained the matter this way:[9]

“For all these years, we have not spoken out, not even with my friend, although he knew that his father worked where I was, and was killed. We lacked the courage to discuss these matters. But at a certain point, faced with certain facts, we decided that it was necessary. It was some years ago, when the Star of David was painted on a few shops in Rome, words like ‘Juden raus‘, ‘Ebrei ai forni‘ [Jews to the ovens] appeared on a few walls, and Nazi skinheads began to be seen here and there. Some people might think they are just boys’ pranks, something not very important, but for us who have experienced these things, seeing the reappearance of such things is unacceptable. This was what compelled me to begin […].”

In the book, Venezia wrote:[10]

“I started to tell the story of what I had seen and experienced at Birkenau a very long time afterwards, not because I didn’t want to speak of these things, but because of the fact that people did not wish to listen; they didn’t want to believe us. When I got out of the hospital, I found myself with a Jew and I began to speak. All at once, I realized that, instead of looking at me, someone behind me was looking and making signs. I turned around and saw one of his friends who told him by means of gestures that I was completely crazy. From that moment I no longer wished to speak. Talking about it made me suffer and when I found myself faced with somebody who didn’t believe me, I thought it was useless. Only in 1992, forty-seven years after my liberation, did I begin to speak about it. The problem of anti-Semitism began to appear in Italy and swastikas were always to be seen on walls […]. In December 1992 I returned to Auschwitz for the first time. […] Today, when I feel well, I feel the need to testify, but it is difficult. I am a very exact person, who loves things done well. When I go to speak in a school and the teacher has not sufficiently prepared his students, it wounds me deeply. Overall, however, testifying in schools gives me great satisfaction.”

In another interview, after talking about anti-Semitic graffiti on walls in Rome, he stated:[11]

“Then I felt that my duty was to tell the story of the Holocaust as I saw it with my own eyes.”

These motivations are not very convincing. In particular, they do not explain why Venezia’s close relatives, his brother Maurice and his cousin Dario, his companions in misfortune from the “Sonderkommando”, also kept silent, just the way he did. But above all, they appear inadequate in view of the “duty to testify,” which should be legal and historical, in addition to ethical. Venezia, in fact, inexplicably, has never made any official declaration, never made a sworn statement, never participated in any trial against his persecutors: not at the Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem (April 1961-May 1962), nor the Auschwitz Trial in Frankfurt (December 1963-August 1965), nor at the Auschwitz Trial in Vienna, against F. Ertl and W. Dejaco (January-March 1972); he has never contributed to the condemnation of his jailers, nor has he enlightened historians on the presumed process of extermination at Auschwitz. Why not? Just because a few know-it-alls might have thought he was crazy?

Venezia’s other cousin, Yakob Gabbai, by contrast, spoke out. At the beginning of the 1990s, he granted an interview to the Israeli historian Gideon Greif, who published it in 1995.[12] Greif also interviewed three other of Venezia’s self-proclaimed companions in misfortune, who mentioned him explicitly: Josef Sackar, registered at Auschwitz under number 182739,[13] Shaul Chasan, 182527[14] and Léon Cohen, 182492,[15] both of them, explicitly mentioned, in turn, by Venezia.[16] The comparison between these testimonies and Venezia’s, as we shall see, is very instructive.

3. The Deportation to Auschwitz

Venezia, born in Salonica (Greece) in 1923, was apprehended in Athens on 25 March 1944 and later deported to Birkenau, which he reached in April. It is curious that, in his book Libro della memoria [Book of Memory], Liliana Picciotto Fargion lists, among the deported Italian Jews, three persons born at Salonica with the last name Venezia, but not Shlomo,[17] perhaps because he was an Italian citizen.[18]

The witness was registered at Birkenau under number 182727. On 11 April 1944 there arrived at Auschwitz from Greece a transport of 2,500 Jews, of whom 320 men (182440-182759) and 328 women (76856-77183) were registered[19].

In the book, he mentions the exact number of inmates registered[20], which he could not have known at the time. It is therefore clear that this information is taken from the Auschwitz Kalendarium.

Venezia’s cousin, Y. Gabbai, of whom he speaks repeatedly, reached Auschwitz in the same transport and was registered under number 182569[21], but, according to him, 700 men were selected upon arrival[22]. He was obviously not familiar with D. Czech’s Kalendarium.

Venezia tells as follows what happened upon his arrival at the camp:[23]

“Instead, the group containing myself, my brother and my cousins was then sent on foot to Auschwitz I.”

But the cousin, Y. Gabbai, described the same event quite differently:[25]

“700 men were selected from the transport, among them my brother and myself. We then had to walk three kilometers on foot[24] to Birkenau.”

Venezia was furthermore tattooed with the 182727 on the same day as his arrival[26], while his cousin, Y. Gabbai, by contrast, was, inexplicably, tattooed with the preceding number 182569 “a few days afterwards”[27].

With respect to Auschwitz camp, Venezia states:[28]

“Inside the camp, immediately to the left, was Block 24: it was the brothel for soldiers and a few privileged non-Jews.”

This brothel was, on the contrary, intended exclusively for inmates. A report of the Lagerarzt (camp physician) of Auschwitz Concentration Camp dated 16 December 1943 states in this regard:

“In October, a brothel with 19 women was created in Block 24. Prior to their employment, the women were tested for Wa. R.[29] and Go.[30] These tests were repeated at regular intervals. The inmates are permitted access to the brothel every evening, after roll-call. An inmate physician always had to be present during visiting hours [to the brothel], as well as an inmate nurse, to carry out the sanitary measures ordered. The supervision was conducted by an SS physician and an SS nurse”

German original:[31]

“Im Oktober wurde im Block 24 ein Bordell mit 19 Frauen errichtet. Vor ihrem Einsetzen wurden die Frauen auf Wa. R. und auf Go. untersucht. Diese Untersuchungen werden in regelmässigen Abständen wiederholt. Der Zutritt ins Bordell ist den Häftlingen allabendlich, nach dem Appell gestatten. Während der Besuchzeit ist immer ein Häftlingsarzt und Häftlingspfleger anwesend, die die angeordneten sanitären Massnahmen durchführen. Die Überwachung besorgt ein SS-Artz und ein S.D.G.”

4. The BIIa Quarantine Camp

The next day Venezia was sent to Birkenau BIIa camp, where they had to remain in quarantine for forty days. He states that, a few days afterwards:[32]

“They made us take a cart, like those utilized for transporting hay. Then we had to drag it in place of the horses. We reached a barracks located at the end of the quarantine [area], the so-called Leichenkeller, or morgue.

When we opened the door, an atrocious odor took us by the throat: the stench of decomposing bodies. I had never passed by in front of that barracks before, and only then did I learn that it was used as a storage area for the bodies of inmates who had died during quarantine, before they were taken to the crematorium to be burnt. A little group of prisoners spent the entire morning in the barracks recovering the bodies of those who had died during the night. The bodies could then remain 15 or 20 days in the Leichenkeller to rot, and those on the bottom were often in an advanced state of decomposition, due to the heat.”

In reality, there was no morgue in the BIIa quarantine camp. In the 19 barracks making up the camp, 14 were used to lodge the inmates, 3 contained lavatories and latrines, one contained an infirmary and one the kitchen. In April-May 1944, 12 barracks were assigned to the inmate hospital; no barracks was used as a morgue.[33]

The languishing of bodies in the morgues of Birkenau for “15 or 20 days” has no basis in reality, which renders Venezia’s tale unsustainable from that point onwards.

On 4 August 1943, SS-Sturmbannführer Karl Bischoff, head of the Zentralbauleitung, replied to SS-Hauptsturmführer Eduard Wirths, Auschwitz garrison physician, who had requested the construction of masonry morgues:

“SS-Standartenführer Dr. Mrugowski, over the course of the conversation on 31 July, declared that the bodies had to be carried into the morgues of the crematoria twice a day, in the morning and evening, to be exact. The separate construction of morgues in the individual subsections is therefore rendered superfluous.”

German original:[34]

“SS-Standartenführer Mrugowski hat bei der Besprechung am 31.7 erklärt, daß die Leichen zweimal am Tage, und zwar morgens und abends in die Leichenkammern der Krematorien überführt werden sollen, wodurch sich die separate Erstellung von Leichenkammern in den einzelnen Unterabschnitten erübrigt”

On 25 May 1944, Dr. Wirths sent a letter to Auschwitz camp commandant, in which he stated:

“In the inmate infirmaries of Auschwitz II concentration camp, there are naturally a certain number of bodies every day, the transport of which to the crematoria is routine, and occurs twice a day, morning and evening.”

German original:[35]

“In den Häftlingsrevieren der Lager des KL Auschwitz II fallen naturgemäß täglich eine bestimmte Anzahl von Leichen an, deren Abtransport zu den Krematorien zwar eingeteilt ist und täglich 2 mal, morgens und abends, erfolgt.”

The transport of the bodies to the crematoria “morning and evening” explains why the “Sonderkommando” was subdivided into two working shifts, day and night, as also declared by Venezia:

“We worked shifts from 8 in the morning until 8 at night, or from 8 at night until 8 in the morning”;[36]

“we worked in two shifts, a day shift and a night shift.”[37]

As regards the term for the alleged barracks-morgue, Venezia confuses the term for the barracks with the term for the semi-underground morgue in Crematorium II/III: ” Leichenkeller,” literally translated, means “corpse cellar”; all the other morgues at Birkenau were in fact on ground level. As we will see, Venezia states that he was assigned to the so-called “Sonderkommando” of Crematorium III, but, rather curiously, he never mentions the term ” Leichenkeller” precisely where he should mention it: ” Leichenkeller 1″ was in fact the alleged homicidal gas chamber.

Where erroneous terminology is concerned, Venezia, repeating what he had already stated in 1995[38], states that the inmates, at Auschwitz, were called “pieces” or “parts” (e.g., of a machine or assembly) (Stücke).[39]

No known document attests to this linguistic usage. On the other contrary, in thousands of documents, the inmates are called, precisely, “prisoners” (Häftlinge); they are sometimes indicated by their registration number only, and sometimes with their name as well.[40] No other witness from “Sonderkommando” and none of Venezia’s companions in misfortune confirms the alleged term of “Stücke“. Venezia’s cousin Y. Gabai stated: “There were no names in the camp, only numbers.”[41]

Venezia continues his narrative as follows:[42]

“At the end of the third week of quarantine, German officials arrived. They did not normally come near, since the maintenance of order was entrusted to the Kapos. The officials stopped in front of our barracks and ordered the Kapos to form a line, as if for roll call. Every one of us had to declare our occupation and we knew to lie. When my turn came, I claimed I was a barber, while Léon Cohen, a Greek friend who was always with us, said he was a dentist, although in real life he worked in a bank. He thought that they would put him in a dental clinic to do the cleaning, at least it would have been warm. For myself, I was convinced that this would permit me to join the prisoners who worked in the Zentralsauna. I had seen that the work was not too difficult and they were in the warmth. In reality, it didn’t happen the way I imagined. The German chose eighty persons, including me, my brother and my cousins.”

But in his interview with Stefano Lorenzetto the number of men selected is given as 70.[43]

The following is Y. Gabbai’s account of the same episode:[44]

“After twenty days – therefore on 12 May 1944 – there was another selection, stricter than the first: two physicians came with two non-commissioned officers. We had to parade naked. A German physician examined us, without saying a word, and chose 300 of the strongest and healthiest.”

In this regard, J. Sackar writes as follows:[45]

“From there, they took us to quarantine: Abschnitt BIIa. There we remained three weeks. […] One evening, when the first transports arrived from Hungary, they conducted another selection and 200-220 Greeks were taken from our transport to special blocks, if I am not mistaken, nos. 11 and 13.”

The first transports of Hungarian Jews arrived at Auschwitz on 17 May 1944.[46]

S. Chasan recounts:[47]

“We remained two weeks in ‘quarantine’. […] The Germans simply came to the ‘quarantine’ and took 200 strong men for the work.”

Finally, L. Cohen declares:[48]

“We remained one month in quarantine. One day, a Jewish physician and a German came to the block for the ‘visit’. Since I knew German, my companions asked me to translate for them. I went over to the physicians and told them that they shouldn’t have assigned us to the Sonderkommando. Some days later, a young German arrived, about thirty years old, who spoke French. […] He then told me that he needed 200 strong men at the railway. […] The man returned the following morning and said: “All the Greeks with me!” There were about 150 persons.”

From the “Quarantäne Liste” (Quarantine List), it appears that on 13 April 1944, 320 Jews from Athens were received in camp BIIa with the registration number 182440-182759 and were lodged in Block 12; the quarantine expired on 11 May, but 30 prisoners were transferred on 5 May[49], therefore Venezia – who remained only three weeks in quarantine – had to form part of this group; even though he mentions the figure of 70 or 80 prisoners, only 30 prisoners were transferred.

With reference to the barracks of the “Sonderkommando”, he adds:[50]

“At any rate, not many of us remained; over the course of a week we were transferred to the dormitory of the Crematorium.”

This would therefore have happened around the middle of May 1944. But according Filip Müller, another self-proclaimed member of the “Sonderkommando”, this occurred “at the end of June” (“Ende Juni“).[51]

5. The First Day in the “Sonderkommando”

Venezia, with the 30 or 70 or 80 or 150 or 200-220 or 300 pre-selected men, was taken into camp BIId “towards two barracks which although they were inside the camp, were isolated from all the others by barbed wire” in which the so-called “Sonderkommando” was located.[52]

“The afternoon afterwards,” the witness recounts, “towards seven in the morning, they took us to Crematorium III, which was surrounded by a grid of barbed wire with the current at six thousand volts. Behind the grid there ran a picket fence three meters high. From outside, we could not see anything of what was happening inside, we saw only the top of the chimney. Hardly had we entered when the Kapo, so as to avoid confronting us with reality suddenly, told us to remain outside in the courtyard to pull up weeds and other work of this kind. At a certain point I noticed that the building had a window as high as a man, and impelled by curiosity, I decided to see what was going on in that crematorium. I approached the window and saw a room full of dead people, so tangled up that at first I could not understand, not like those we had seen in the barracks,[53] but recently dead, not yet decomposed. We couldn’t believe it.”[54]

The next day was 6 May 1944. At the time, Crematorium III (like Crematorium II) was not surrounded by any “picket fence three meters high” which would have cut off the view of the respective courtyards, as shown in particular by photograph no. 153 in the Auschwitz Album, taken on 26 May 1944, which shows that the eastern half and a good part of the courtyard of Crematorium III were clearly visible because it was surrounded only by a barbed-wire fence.[55] This photograph also appears in Venezia’s book, with a misleading caption: “Group of women and children – Hungarian Jews – about to enter Crematorium II.”[56] The photographs in the Auschwitz Album taken later show in fact that this group of persons travelled up the Hauptstrasse (Main Street) bypassing Crematoria II and III, and through the Ringstrasse (ring road),[57] ending up in the little forest near the small lake located east of Crematorium IV.[58]

The story of the picket fence is taken from F. Müller’s book, which says:[59]

“Beforehand, Moll had caused a barrier to be constructed here [near the Bunker] and in the courtyard of Crematoria IV and V, about 3 meters high, consisting of long stakes fixed in the ground, sticks and dry branches, to prevent those outside from casting indiscreet glances into the extermination areas.”

Venezia obviously did not fully adhere to this passage, since he attributes to Crematorium II or III that which F. Müller reports about the “Bunker” and Crematoria IV and V.

Standing in the courtyard of the crematorium, Venezia noted “that the building had one window at the height of a man”. Recounted this may, the story is rather ingenuous, since along the entire outside perimeter of the crematorium there were no fewer than 47 windows the height of a man[60]. There were 47 windows to choose from! In the book, Venezia returns to the episode, writing:[61]

“The first day at the Crematorium, we remained in the courtyard without entering the building. In those days, they called it Crematorium I; they did not yet know of the existence of the first Crematorium at Auschwitz I. Three steps led to the interior, but instead of making us enter, the Kapo made us walk around it. One man from the Sonderkommando came to tell us what we were supposed to do: cut the weeds and clean the grounds a little. This was not useful work; the Germans probably wanted to keep us under observation before making us work inside the Crematorium. When we returned the next day, they made us do the same things. Although they had strictly prohibited it, impelled by curiosity I approached the building to see what was going on from the window. When I got close enough to have a look, I was paralyzed: on the other side of the window I saw piles of corpses, all on top of each other, bodies of persons who were still young. I returned to my companions and told them what I had seen. They then went to look for themselves, carefully, without being noticed by the Kapo. They returned with their faces contorted, incredulous. They did not dare to think what could have happened. I only understood later that those bodies were the ‘back-up’ from a preceding convoy. They had not been burned before the arrival of the new convoy, and they had placed them there to make room in the gas chamber.”

I note first of all that, in this version, the scene takes place at Crematorium II instead of Crematorium III. Venezia has furthermore abandoned the unsustainable story of the “picket fence three meters high”. I add that the windows of the crematorium were double windows, and were all protected by an iron grid, non-negligible details which could not escape an outside observer.

According to another self-proclaimed member of the “Sonderkommando”, Henryk Tauber, on the ground floor of Crematorium II and the area designated “Waschraum und Aufbahrungsraum” (washroom and layout-out room), towards which the freight elevator travelled, came to be used in March-April 1943 as a “morgue.”[62]

But even if one wished to extend this function to Crematorium III and in May 1944, it nevertheless extraordinarily remains the case that Venezia, among the 22 windows which opened into that facade of the crematorium, claims to have gone to have a look precisely through the pair of windows of the room in question.

For F. Müller, this area was used for the execution.[63] Of this presumed use, however, Venezia knows nothing: for him the executions with a bullet in the neck were performed in the oven rooms, near the “corner of the last oven,”[64] nor did he mention the use of an area on the ground floor for the storage of a “back-up” of bodies.

The story of the “back-up from a preceding convoy” is furthermore disproved by the Kalendariumof Auschwitz, according to which the last gassing before 6 May 1944 was performed on 2 May, but the presumed 2,698 victims,[65] based on the cremation capacity described by Venezia,[66] would have been cremated in less than two days; on the other hand, the first gassing subsequent to that date is said to have occurred on 13 May.[67] In the book, “the morning after” became “a few days after our arrival”[68], but this did not change the conclusion which flows from his account: Venezia in Crematorium II or III could not have seen the group of bodies of presumed gassing victims.

Venezia’s cousin described the event as follows:[70]

“At the beginning of the week, on Monday 15 May, the group was divided. Some went to the Crematorium II [= III], we were taken to Crematorium I [= II]. In our group there were primarily Greek Jews, among them Michel Ardetti, Josef Baruch from Corfu, the Cohen brothers, Shlomo and Maurice Venezia, myself and my brother Dario Gabai, Leon Cohen, Marcel Nagari and Daniel ben Nachmias. They told us that the first night we were not supposed to work, only observe. I recall that towards 5:30 in the afternoon, a transport arrived from Hungary.[69] The old workers said that we new arrivals had to watch carefully, since within a few minutes they [the deportees] would no longer be alive. We did not believe it. After a little while they order us to follow the workers downstairs, to see what was happening down there. This was now our work, we were told. Outside, there was [written] ‘Shower,’ in Polish, German, Russian and English.

[Question] What did you see when, for the first time, the door of the gas chamber opened before you?

[Gabbai] I saw bodies, one on top of the other. There were about 2,500 bodies.”

For J. Sackar, S. Chasan and L. Cohen, by contrast, on the first work day, the new detainees of the “Sonderkommando”were taken directly to the “Bunker,” as we will see in paragraph 8.

6. “Bunker 2”

In the interview published by Il Giornale, Venezia described his first workday in the so-called “Sonderkommando” without mentioning at all the anecdote relating to the crematorium:[71]

“The next day [6 May 1944] they made us walk through a little forest. We arrived in front of a little peasant cottage. Woe to anybody who moved or said a word. We all stopped in a corner to wait. Suddenly we heard voices in the distance: there were entire families, with little children and grandparents. They forced them to take their clothes off in a hurry. Then they made them enter the little cottage. A truck arrived with the insignia of the Red Cross: an SS man got out, [and] using a device, opened a little window and allowed a can of stuff, about two kilos, to fall inside. He closed it and went away. Ten minutes afterwards, a door opened from the part facing the entranceway. The chief called to us to drag out the bodies. We had to throw them into the fire in a sort of swimming pool 15 meters away.”

This narration refers to the so-called “Bunker 2,” a farmhouse outside Birkenau camp, supposedly transformed into a homicidal gas chamber in 1942. In reality, this presumed extermination installation, as I have shown in a specific study,[72] never existed. It never appears in any German document, either under the name “Bunker” or under any other name, not even a “code name”.

The Soviet commission of inquiry, which conducted its activity at Auschwitz in February-March 1945, was completely ignorant of the term “Bunker”: it always used the expression “gas chamber” (газовая камера, gazovaja kamera) Numbers 1and 2. The witness par excellence, Szlama Dragon, in the first deposition rendered before a Soviet examining magistrate on 26 February 1945, also spoke of “gazokamera [газокамерa] Numbers 1 and 2″ and explicitly stated that this was the official designation. H. Tauber, in his deposition dated 27 and 28 February 1945, referred only to “gas chambers” (“газовые камеры,” gazovie kameri). The term “Bunker” appeared for the first time in the deposition of Stanisław Jankowski (also a self-proclaimed member of the “Sonderkommando”) dated 16 April 1945.[73]

Venezia was not aware that, according to the official version, this “Bunker” was put back in operation on the arrival at Auschwitz of the Hungarian Jews (since the “gas chambers” of the crematoria were unable to dispose of the victims), therefore not before 17 May 1944. The same thing is true of the presumed cremation “swimming pool”. D. Czech states in fact that Rudolf Höss, the commandant at Auschwitz, in the course of preparations for the extermination of the Hungarian Jews, ordered the reactivation of “Bunker 2” on 9 May 1944.[74] F. Müller writes in this regard that “camp commandant Höss first appeared in the vicinity of the crematoria at the beginning of May; a few days later, Hauptscharführer Moll arrived,”[75] who ordered the excavation of “five ditches behind Crematorium V”. F. Müller adds:[76]

“Every day, in the vicinity of Bunker V, a very large number of prisoners also arrived to dig ditches.”

The period is precisely that of the presumed sending of Venezia to “Bunker 2”: at the time, therefore, he, possibly would have been present only at the digging of the ditches, but not at the spectacle of burning pits. Moreover, as I have already noted, at that time not even one transport of Jews arrived who could have been gassed.

Venezia was also unaware that the supposed “Bunker 2,” according to Sz. Dragon, was sub-divided into four areas, and had 4 exits and entrances, as well as 5 Zyklon B introduction ports. For D. Paisikovic, on the other hand, it had 3 areas,[77] while based on the topographical survey of Auschwitz Museum dated 29 July 1985, it had 7 areas.[78]

On the other hand, the expression “take our clothes off in the cold”[79] not only does not suit the period (6 May), but is also in conflict with the official version, according to which at “Bunker 2” three barracks were built in which the victims undressed.

I would like to open a parenthesis here. The historian Marcello Pezzetti, in his essay “La Shoah, Auschwitz e il Sonderkommando” included in Venezia’s book, instead of indicating this error, attempts to cover it up, by stating:[80]

“In this period of maximum camp extermination capacity, the Nazi authorities reactivated Bunker 2 (without undressing barracks next door, the inside of which was divided into two parts […].“

But the witness F. Müller, who is certainly a bit more important than Venezia, has written in this regard that “the undressing rooms in which the victims were supposed to take off their clothes before being gassed were located in three wooden barracks.”[81] Sz. Dragon has also confirmed that, upon the reactivation of “Bunker 2,” “three other barracks were built.”[82]

Pezzetti is proven wrong even by the diagram of Birkenau reproduced in the book, in which “Bunker 2” (designated “M 2”) appears equipped with two undressing barracks![83]

Returning to the statements of Venezia, the gas-tight windows in the disinfestation chambers (and supposed homicidal gas chambers) did not open “with a device,” but with a simple butterfly wrench. The witness confuses the opening system of the windows with that of the cans of Zyklon B, which, specifically, were opened with a special device, which was called a “Schlageisen” (chisel).

Furthermore, it is not clear how Venezia could have established that “approximately two kilos” of Zyklon B had been introduced in the “cottage,” because this was packaged in cans of various sizes, from 100 to 1,500 grams of hydrocyanic acid, which he nevertheless never describes.

In the book, Venezia recounts the same anecdote in a more prolix manner. I will cite the essential passages:[84]

“We arrived before a cottage which was called, as I learned later, Bunker 2 or “the white house” and precisely at that time the murmur became more intense.

Bunker 2 was a small farmhouse with the roof covered with leafy branches. They ordered us to stand over to one side of the house, near the road which passed by in front of it, from where we couldn’t see anything, neither to the right or left.”

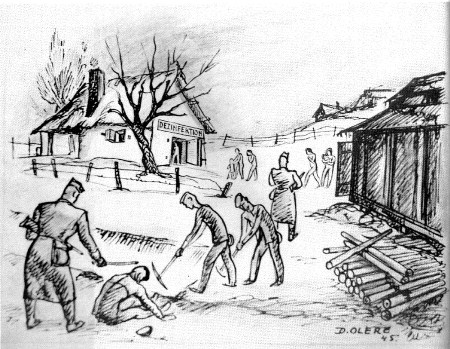

Two pages later the book reproduces a drawing by the self-proclaimed member of the “Sonderkommando” David Olère, dating back to 1945, showing “Bunker 2.”[85] The drawing shows a house (the presumed “Bunker 2”) with a door in the centre of the facade, a little window in the centre of the visible side of the building and a roof apparently covered with leafy branches. In realty, according to the deposition of Sz. Dragon dated 10-11 May 1945,[86] the roof was of straw,[87] as confirmed on 10 August 1964 by D. Paisikovic.[88]

I would like to add that the drawing by Sz. Dragon of “Bunker 2”[89] is in flagrant contradiction to that by D. Olère, which moreover presents several elements of fantasy[90], while that of D. Paisikovic is in conflict with both.[91]. Therefore the detail of “roof covered with leafy branches” is the product of a misunderstanding of the drawing by D. Olère.

Venezia then says that 200-300 victims arrived: “The persons were compelled to undress in front of the door”. No mention of the purpose-built undressing barracks, not even here.

Later in the narrative, there appears both the mention of the SS which “with a device opened a little window,” and the reference to “approximately 2 kilos” of Zyklon B.

Venezia adds:[92]

“As for us, they ordered us to go behind the house, where I had noticed a strange glow upon my arrival. While we were approaching, I noticed that this glow was the glare of the fire which was burning in the pits, about twenty meters away.”

He had previously mentioned only one pit, “a sort of swimming pool,” or “a pit like a swimming pool”:[93] here, by contrast, he speaks of “pits,” in the plural, without even bothering to tell us how many there were. This matter is in fact a rather difficult one, since, in this regard, the eyewitnesses contradict each other, claiming that there were 1, 2 or 4 pits, that they were 50 or 30 meters long, 10 or 6 meters wide and 3 or 4 meters deep.[94]

Venezia was also unaware that, in 1944, “Bunker 2” (according to other witnesses) was renamed “Bunker V” (F. Müller) or “Bunker 5” (D. Paisikovic), so that Jean-Claude Pressac made the Solomonic decision to call it “Bunker 2/V.”[95]

7. The First Workday at the “Bunker” According to Venezia’s Companions in Misfortune

In this regard, J. Sackar stated as follows on his first day in the “Sonderkommando”:

“I remember the first day well. We were in Camp D [BIId] and one evening they took us behind the last crematory building [hinter das letzte Krematoriumsgebäude], where I saw the most horrible atrocities of my life. That evening a small transport had arrived. We did not have to work; they had taken us there so that we would get used to looking. There was an open pit, called ‘Bunker,’ to cremate the bodies. The bodies were brought from the gas chambers to these ‘Bunkers,’ where they were thrown in and burned in the fire”[96].

The “last crematorium” was Crematorium V, therefore the witness located “Bunker 2” in the courtyard outside this crematorium!

At the question: “Can you describe the ‘Bunker’?,” the witness answered:[97]

“Yes, it was a big pit, where the bodies were carried and thrown in. The pits were deep excavations; wood was piled up down on the bottom. The bodies were carried here from the gas chamber and thrown in the pits. The pits were all outside, in the open air. There were a few pits in which the bodies were burned.”

For J. Sackar, therefore, “Bunker 2” was not a peasant cottage transformed into a gassing installation, but rather a “big pit” in which the bodies murdered in the chambers of Crematorium V were cremated!

This harebrained artifact of “Holocaustology” appeared in the testimonies of his companions in misfortune.

S. Chasan, in fact, still with reference to the first working day, stated:[98]

“We walked and walked. While we were walking, we wondered: ‘Where are we going to work?’. The answer was: ‘In the factory’. Finally, we reached a small forest. We looked around in the small forest and what did we see? A small peasant cottage, an isolated cabin. We approached, we reached it and when the door was opened, I saw something horrible. Inside it was full of bodies from a transport, more than 1,000 bodies. The entire building was full of bodies.”

This “peasant cottage,” therefore, had one single gas chamber with one single door. As I have already noted, this is in contradiction to the statements of Sz. Dragon and D. Paisikovic, both of whom in turn contradict each other.

For S. Chasan as well, the “Bunker” was not the “peasant cottage,” but rather a pit:[99]

“We had to pull the bodies out. There was a basin there, a deep pit which was called ‘Bunker.'”

In response to the interviewer’s question: “Where was this basin located?,” the witness added:[100]

“It was called ‘Bunker’. Now, when I returned to Auschwitz, I found neither the pit nor the house. It must have been located behind Crematorium IV [= V].”

Thus, S. Chasan also located “Bunker 2” in the courtyard of crematorium V.

And finally this is the tale of L. Cohen:[102]

“The Germans didn’t take us to the buildings of the crematorium plant, but to the cremation pits. There I saw several carts beside the pits and very close by, a building with a small door. It was then clear to me that they were asphyxiating people with gas. We waited outside for about 15 minutes, then, at the order of the Germans, we had to open the doors. The bodies fell in piles and we began to load them onto the carts. They were little carts like mining carts. Much smaller than railway cars. The bodies were carried to the pits. In the pits, the bodies were arranged this way: one layer of bodies of women and children,[101] above a layer of wood; then a layer of bodies of men, and so on, until the pit, a good three meters deep, was completely filled. Then the Germans poured gasoline into the pit. The mixture of dead bodies and wood burned furiously.”

Summarizing briefly, for Venezia, the new prisoners of the “Sonderkommando” were first taken to Crematorium II or Crematorium III, where they saw bodies from a window, but were not permitted to enter the gas chamber; Y. Gabai, by contrast, states that on 15 May 1944 they were taken to Crematorium II, where they saw the bodies of 2,500 Hungarian Jews in the gas chamber from a transport having arrived in Birkenau only two days after. The witness says nothing about working at “Bunker 2”. J. Sackar asserts that the prisoners were directed into the courtyard outside crematorium V, where there was a pit which was called “Bunker”. S. Chasan makes similar statements. L. Cohen, by contrast, who was not even aware of the designation “Bunker,” defines the supposed extermination installation simply as a “a building”. He introduces into his narrative “carts” to carry the bodies to the pits, undoubtedly more comfortable than the system described by Venezia:[103]

“Carrying one body between only two people on that muddy terrain, where the feet sank in the mud was not easy, but for one person, it was almost impossible […].“

S. Chasan, upon his arrival at “Bunker 2,” found it already full of 1,000 bodies. L. Cohen, by contrast, had to wait 15 minutes before seeing the bodies. Venezia, it is hard to see how, succeeded in seeing the living victims as well, who were however not 1,000 but 200-300:[104]

“Curious as always, I approached to see what was going on and I saw whole families who were waiting in front of the cabin: young people, women children. Two, three hundred in all.”

Finally, according to J. Sackar, the new members of the “Sonderkommando” did not work at the “Bunker,” but limited themselves to watching, while for Venezia they were compelled to remove the bodies from the gas chamber and throw them into a burning pit; for L. Cohen, by contrast, they had to arrange them in layers in an empty pit.

I conclude this brief panoramic overview with another eyewitness testimony, that of Miklos Nyiszli, self-proclaimed physician in the “Sonderkommando” in the same period in which Venezia was working there. He wrote that “Bunker 2,” never referred to in this manner by Nyiszli, but described as “a long decrepit building with a stubble roof,” “a peasant cottage,” was not a gassing installation, but rather a simple “undressing room” for the Jewish victims, who did not die in a gas chamber, but rather, from a gunshot to the back of the neck on the edge of two enormous “cremation pits”[105].

8. The “Cremation Pits” in the Area of “Bunker 2”

The existence of “cremation pits” in the spring-summer of 1944 in the area of “Bunker 2” is one of the recurrent themes of Auschwitz “memory literature”. L. Cohen—to remain with our eyewitnesses, informs us that “the pit” (die Grube) was “a good three meters deep,”[106] while according to S. Chasan “the pit was very deep, I believe about four meters.”[107]

But none of the aerial photographs taken by American and British aviation in 1944 show “cremation pits” or smoke in this area.[108]

What is more, at the time, the ground-water table in the area of Birkenau was 1.2 meters below ground level,[109] therefore the cremations would have taken place underwater!

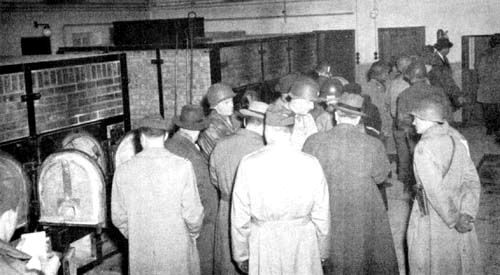

A quick reference also to the “cremation pits” of the courtyard of Crematorium V. In confirmation, Venezia’s book reproduces two photographs.

The first shows “men from the Sonderkommando near one of the mass graves of Crematorium V.”[110] The caption is doubly erroneous. In keeping with the standard terminology of the Holocaust, since smoke appears in the photograph, one should refer to a “cremation pit,” as is commonly done. The related footnote in the book asserts that “at the end of spring 1944, there were five open-air cremation pits around Crematorium V,”[111] but this is arbitrary and false.

Arbitrary, because the testimonies of the self-proclaimed ex-members of the “Sonderkommando” are contradictory: the supposed pits were 2 for S. Jankowski, 3 for C.S. Bendel, 3 for H. Tauber according to the deposition rendered to the Soviets, 5 according to the deposition rendered by him to J. Sehn and also for Sz. Dragon and F. Müller.[112] Every witness, furthermore, attributed conflicting dimensions and capacities to these dimensions.[113]

False, because only one single cremation site existed in this area, with a surface area of approximately 50 square meters. This single site appears both in the photograph mentioned above, and in the aerial photograph of Birkenau taken by the British on 23 August 1944, which is precisely the second photograph in the book on the theme of the “cremation pits.”[114] The column of smoke which can be seen beside crematorium V originates precisely from this site, as I have demonstrated with enlargements of the available photographs.[115]

According to F. Müller, the alleged five “cremation pits” in this area should have measured 40-50 meters in size and 8 x 2 meters deep,[116] therefore their total surface area should have been an average of 1,800 square meters. The aerial photographs of Birkenau show, by contrast, one single cremation site of approximately 50 square meters. Naturally, the “pits” of F. Müller would also have been full of water for at least 60% of their depth.

9. The Recovery of Human Fat from the “Cremation Pits”

In the interview published in Il Giornale, Venezia, incredibly, repeats the absurd story of the recovery of human fat from the “swimming pool”:[117]

“Yes, but the first night they assigned me to this open air crematorium. There was a sloping drain all around where they recovered the fat dripping from the pyre. I had to pick it up and throw it back onto the bodies to make them burn faster. You have no idea of how combustible human fat really is.”

And in the book he repeats:[118]

“The pits were sloping; the human fat produced by the burning bodies dripped along the bottom into a corner, it a sort of hollow had been dug to collect it. When the fire threatened to go out, the men took a bit of the fat from the hollow and poured it onto the bodies to enliven the flame. I saw something of the kind only here, in the pits of Bunker 2.”

This story, invented immediately after the war, has received the official sanction of F. Müller, who embroidered it in a very detailed manner. According to him, however, the supposed “cremation pits” were equipped with two little channels 25-30 cm. in width, which, in the centre of the pit, ran sloping along the central axis and flowed out into two deeper little holes in which the liquid human fat was collected, which was picked up in a bucket and thrown onto the bonfire.[119]

As I have demonstrated in a specific study[120], this little story is nonsensical simply because of the fact that, while the ignition temperature of the light hydrocarbons which formed as a result of the gasification of the bodies is approximately 600°C, the ignition temperature of animal fats is 184°C, therefore in such an installation the human fat would burn immediately. Also, because the ignition temperature of seasoned wood is between 325-350°C. Moreover, if—just another of the many miracles interspersed throughout the lives of “Sonderkommando” survivors—the liquid human fat could have been able to drip through the flames on the bottom of the pit, flow over burning branches and flow out into the lateral collection ditches, Venezia, together with F. Müller, would have had to approach and collect it at the edge of a “cremation pit” in which there was an immense bonfire raging away at a minimum temperature of 600°C!

10. The Gas Chamber in Crematorium III

Initially, to Fabio Iacomini, Venezia had claimed to have been assigned to Crematorium III[121]. To Stefano Lorenzetto, by contrast, he said: “I was assigned to Krematorium 2, the largest of the four[122] functioning at Birkenau.”[123] In the book, he returns to his first version:[124]

“The truce didn’t last long: the next day we had to recommence working and I was assigned to a little group of about forty persons at Crematorium III.”

In the plans of Birkenau and in the official documentation—beginning with the explanatory reports (Erläuterungsberichte)[125] and the cost estimates (Kostenanschläge or Kostenvoranschläge)[126] of the camp and of the “turnover” (Übergabeverhandlung) of these installations,[127] the Birkenau crematoria were normally referred to as II, III, IV and V; in a few documents, the designation I, II, III and IV appears. But Venezia never mentions this double numbering system, which was obviously unknown to him. If he had really been employed in the Sonderkommando, he would have known the correct number of the crematorium in which he worked. The fact that he alternates between one number and the other indiscriminately shows that his account is based on what he has read, instead of on personal experience.

Of what was the gas chamber constructed? Surprisingly, in the book Venezia does not describe it at all: he indicates neither the dimensions, nor its location within the building, how it was accessed, how it was rigged out on the inside, whether it was divided into two areas (as stated by H. Tauber) or whether it consisted of one single room (as declared by M. Nyiszli).

Here he has also wasted an excellent opportunity to provide a definitive clarification, with the authority of his eyewitness testimony, of one of the most important and controversial points of the supposed extermination process in Crematoria II and III: the structure of the supposed devices for the introduction of Zyklon B into the gas chamber. Were they simple hollow “square sheet-metal columns” with holes in each of the four surfaces, as claimed by M. Nyiszli?[128] Did they have “a spiral” inside to distribute the Zyklon B uniformly, as stated by F. Müller?[129] Or perhaps they were not of sheet metal, but of metallic mesh, with a square section of 70 cm on each side, as testified by M. Kula (the self-proclaimed builder of the devices),[130] or 35 cm, as affirmed by J. Sackar,[131] or 25 cm, as declared by K. Schultze?[132] And if they were of metallic mesh inside, did they have a short “Zyklon B diffusion and recovery cone” which was inserted into the higher part of the device, as asserted by Kula, or a “little basket” which was pulled upwards “with the help of an iron wire,” as we are informed by H. Tauber?[133] Or, as S. Chasan informs us, did they consist of perforated round metallic tubing, which did not, however, reach the floor, but had a free empty space at the bottom to recover the Zyklon B granules?[134] Or, as maintained by J. Weiss, “There were three columns for the Ventilators, through which the gas was poured in”?[135] Or, according to J. Erber’s description, the devices all had the following characteristic in common: they were iron pipes (Eisenröhre) but, at the same time, “they were surrounded by a steel network” and had a “sheet metal container” (Blechbehälter) inside, which they could pull up and down by means of a cord?[136]

With regards to all this, Venezia tells us absolutely nothing: from his eyewitness testimony; we learn neither how the supposed Zyklon B introduction devices were designed, how many of them there were, how they were employed, or even if they really existed! And judging from the fact that, according to him, the Zyklon B was simply “thrown on the floor” inside the gas chamber—as we shall see below—he knows nothing whatever about such devices.

To obtain a meager description of the supposed gas chamber, we must return to his testimony of 1995: “This was a large room, on the ceiling there was a fake shower head every meter,”[137] or to his testimony in January 2001, which is no less terse:[138]

“The people were convinced that they were going to take a shower and therefore there was a large room with so many fake shower heads.”

These statements require clarification.

The turnover document (Übergabeverhandlung) for Crematorium III to the camp administration, dated 24 June 1943, assigns “14 Brausen” (shower heads) to Leichenkeller 1, the supposed homicidal gas chamber.[139] These shower heads, starting with Pressac, are usually considered “fake”. The reality is quite different. They were the implementation of a well-documented previously existing plan.

On 16 May 1943, Bischoff sent Hans Kammler, Amtsgruppenschef C of the SS-WVHA, a “Report on measures taken to implement the special program ordered within the KGL [prisoner of war camp] Auschwitz by SS-Brigadeführer and Generalmajor der Waffen-SS Kammler, Doctor of Engineering” (Bericht über die getroffenen Massnahmen für die Durchführung des durch SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Waffen-SS Dr. Ing. Kammler angeordneten Sonderprogrammes im KGL. Auschwitz) in which, at Item 6, we read:

“Disinfestation plant. An Organization Todt disinfestation plant for the disinfestation of prisoners’ clothing is anticipated in each of the individual parts of the BAII camp[140]. To ensure the thorough physical disinfestation of the prisoners, storage heaters and boilers should be mounted in the two existing prisoners’ bathrooms in the BAI so that hot water will be available for the existing shower room. Heating coils are moreover to be mounted inside the waste incinerator of Crematorium III to obtain the [hot] water needed for a shower installation to be built in the cellar of Crematorium III. With regards to execution of construction for this plant, we have negotiated this with the firm Topf and Sons of Erfurt”.

German original:[141]

“Entwesungsanlage. Zur Entwesung der Häftlingskleider ist jeweils in den einzelnen Teillagern des BAII eine OT-Entwesungsanlage vorgesehen. Um eine einwandfreie Körperentlausung für die Häftlinge durchführen zu können, werden in den beiden bestehenden Häftlingsbädern im BAI Heizkessel und Boiler eingebaut, damit für die bestehende Brauseanlage warmes Wasser zur Verfügung steht. Weiters ist geplant, im Krematorium III in dem Müllverbrennungsofen Heizschlangen einzubauen, um durch diese das Wasser für eine im Keller des Krematoriums III zu errichtende Brauseanlage zu gewinnen. Bezüglich Durchführung der Konstruktion für diese Anlage wurde mit der Firma Topf & Söhne, Erfurt, verhandelt.”

The showers, therefore, were real.[142]

In the book, Venezia limits himself to saying:[143]

“After having undressed, the women entered into the gas chamber, waited, thinking that they were in a shower room, with the faucets up high.[?]”

In addition to the supposed fake shower heads, Venezia had previously mentioned only the door of the supposed gas chamber:

“Then they closed the door, which was made like that of a refrigerator, with a little porthole to be able to see inside.”[144]

“Finally, they closed the door, similar to that in the refrigerator in butcher shops, a double door with a peephole in the middle to see inside”[145].

In the book, Venezia only added that the door “to the inside was protected by a few iron bars to keep the victims from breaking the glass”[146]—a detail which is however taken from a drawing by D. Olère, to which I will return shortly—which shows precisely the open door to the gas chamber with the spy-hole protected on the inside by a square grill.[147] The drawing, in turn, is freely inspired by the gas-tight door with spy-hole equipped on the inside with a hemispheric protection grid, which was found in the Bauhof (construction materials warehouse) of Auschwitz in 1945, as appears in the photographs reproduced by Pressac.[148] Without going into further detail, I will restrict myself to noting that the door of Leichenkeller 1 (supposed gas chamber) of Crematorium III was built without a protection grid.

Bischoff’s letter to the DAW (Deutsche Ausrüstungswerke) offices dated 31 March 1943 makes reference to an order dated 6 March concerning “a gas-tight door” (Gastür)[149] 100/192 for Leichenkeller 1 of Crematorium III, BW 30a,” which had to be “built exactly according to the type and dimensions of the cellar door (Kellertür) of Crematorium II in front, with a spy-hole sealed with double 8 mm glass with rubber seal and mounting (mit Guckloch aus doppelten 8-mm-Glas mit Gummidichtung und Beschlag).”[150] With regards to the door of Crematorium II, in his deposition dated 24 May 1945, before examining magistrate J. Sehn, H. Tauber, who had seen this door in the Bauhof,[151] declared that the door of the supposed gas chamber had a little window “protected on the inside by a metallic grill in the form of a half-moon,” but because the latter was regularly damaged by the victims, “the spyhole was hidden by a board or a metal sheet.”[152]

Venezia dwells, instead, on the description of the gassing process and the appearance of the victims. In this regard he states:[153]

“At last the German arrived with the gas. He took two prisoners from the Sonderkommando to raise the trapdoor from the outside, above the gas chamber, and introduced the Zyklon B. The cover, of cement, was very heavy. The German would never have taken the trouble to lift it all by himself; we did it together. Sometimes me, sometimes others.”

This statement is in radical contradiction with all the more widely believed statements. For example, the witness F. Müller states that the Zyklon B was poured by two SS “disinfectors”[154]. Still more clearly, the witness M. Nyiszli, whom Venezia mentions in the books as “Hungarian Jewish physician and assistant to Mengele”[155], states:[158]

“In this precise moment, we heard the noise of an automobile. It is a luxury car, bearing the insignia of the Red Cross International. Two SS officers get out of the car and an S.D.G. Sanitätsdienstgefreiter (non-commissioned officer from the Health Service)[156]. The non-commissioned officer is carrying four green tin cans. He walks across the lawn where, every thirty meters[157], small concrete pots protrude from the ground. After putting on a gas mask, he raises the lid of the chimney pot, which is also of concrete. He opens a can and pours the contents, a purplish, granular material, into the mouth of the chimney.”

And here is the related testimony of H. Tauber:[159]

“[SS-Rottenführer] Scheimetz opened the tin with the help of a special punch and a hammer, then poured the contents into the gas chamber and closed the opening [of the small chimneys] with a concrete lid. As I have already said, there were four of these small chimneys. In each of them, Scheimetz poured the contents of a smaller tin of Zyklon. They were containers with a yellow label. Before opening them, Scheimetz put on a gas mask. He had the mask on when he opened the tins with the Zyklon and poured the content into the small chimneys of the gas chamber. Besides Scheimetz, other SS carried out this task, but I have forgotten their names.”

This is in later contradiction to the following statement by Venezia:[160]

“Some people say that the SS wore gas masks, but I never saw Germans wearing them, neither to pour the gas nor to open the door.”

Incredibly, Venezia is unaware of the story of the small exterior chimneys for the introduction of Zyklon B into the gas chamber, since he speaks of a simple “trapdoor,” obviously installed on the roof of the area, which had a concrete cover. This detail originates from the deposition of H. Tauber.[161] And, mentioning “the trapdoor,” he reveals that he does not even know that the supposed openings for the Zyklon B in Leichenkeller 1 of Crematoria II and III should have been four in number.

The filling of the gas chamber by the SS, described by Venezia, contains an obvious contradiction in terms:[162]

“The men were instead sent into the gas chamber at the end, when the room was already full. The Germans made about thirty strong men enter last, in such a way that, pressed by blows, driven like animals, they had no choice but to push the others ahead to enter and escape the blows-“

But “strong men” were not sent to the gas chamber but rather, to work.

And here is the description of the bodies in the gas chamber:[163]

“There we found them grasping each other, each one in desperate search of a bit of air. The gas, thrown on the floor, developed acids [sic] from the bottom; everyone attempted to reach the air, even if they had to climb on top of each other, until the others died too.”

This scene is taken, very unwisely, from the testimony of M. Nyiszli. Nyiszli in fact wrote:

“The bodies were not lying here and there throughout the room, but piled in a mass to the ceiling. The reason for this was that the gas first infused the lower layers of air and rose but slowly towards the ceiling. This forced the victims to trample one another in a frantic effort to escape the gas. Yet a few feet higher up the gas reached them.”[164].

The witness had built this fictitious scene on the supposition that the gas employed for homicidal purposes was not hydrocyanic acid (the active ingredient of Zyklon B), but “chlorine in a granulated form,”[165] and it is known that chlorine has a greater density than air,[166] so that if this gas had been introduced into the chamber, it would have first filled the lower layers of air and would have climbed slowly upwards. But as the historian Georges Wellers has noted[167][168]:

“Hydrocyanic acid vapor is lighter than air, and therefore rises in air.”

Precisely the contrary of that asserted by M. Nyiszli. The scene described by him and borrowed by Venezia is therefore completely invented.

In this non-description of the gas chamber, the most incredible aspect, as I have noted above, is the absence of any reference to the presumed devices of metallic mesh for the introduction of Zyklon B. For years now, revisionist researchers have shown that these presumed devices are a simple literary expedient without any documentary or material basis.[169] Venezia, instead of contradicting them, at least on the level of eyewitness testimony, on this fundamental point of the story of the homicidal gassings in Crematoria II and III of Birkenau, does not even touch on the question!

Venezia says practically nothing about the ventilation system of Leichenkeller 1. All we are able to glean from his testimony is that, after the ventilation was started, “for about twenty minutes we heard an intense buzzing, like a machine which was sucking the air”[170] and that “the ventilator continued to purify the air”[171](emphasis added).

But the ventilation installation of Leichenkeller 1 consisted of two ventilators: an intake, which blew the air in (Belüftung), and an outlet, which sucked the air out (Entlüftung).

The most surprising thing is nevertheless the fact that, while the supposed gas chamber of Crematorium III, for access, required approximately twenty minutes of mechanical ventilation, that of “Bunker 2,” which was not equipped with any ventilation installation at all, could be entered immediately after the doors were opened:[172]

“Ten minutes afterwards a door was opened opposite the entrance. The chief called me to drag the bodies out.”

Still more incredibly, Venezia never mentions gas masks, without which the prisoners in the “Sonderkommando” would have been gassed in turn: certainly, in “Bunker 2,” very probably in Crematorium III. F. Müller has written in this regard:[173]

“While the dead were carried out of the gas chamber, the carriers of bodies had to wear gas masks, because the ventilators could not completely exhaust the gas. Above all, among the dead there were always residues of the toxic gas which were released during the clearing of the gas chamber.”

One last observation. Venezia states:[174]

“The undressing lasted an hour, an hour and a half, often two hours, it depended on the persons: the older they were, the more time it took and the first ones to enter the gas chamber could remain there waiting for more than an hour.”

And here is L. Cohen’s related declaration:[175]

“[Question] How long did they remain in the undressing room?

11. The Transport of the Bodies to the Ovens of Crematorium III

Venezia describes the transfer of the bodies to the ovens as follows:[176]

“In the end, the easiest thing was to take a cane and drag the body with the crook of the cane hooked around the neck. You see it in a drawing by David Olère. With all the old persons doomed to die, there was certainly no shortage of canes.”

The drawing in question is reproduced on the following page of the book. It shows the entrance to the supposed gas chamber, with the door open (equipped with a peephole protected by a square grill, of which I have spoken); one inmate is at work at the entrance, another is dragging the body of a woman by its left hand, and the body of child by its left hand, towards the ovens. In the left-hand part of the drawing we see the edge of the last 3-muffle oven. In this drawing it is obvious that the instrument with which the above-mentioned prisoner is dragging the woman cannot be a walking cane, because the instrument in the prisoner’s hand possess a crook-like curve, which, by contrast, according to Venezia, should have been hooked around the woman’s neck. The instrument is more probably a belt pulled around the woman’s neck. The belt is in fact mentioned, in various variants by other witnesses. M. Nyiszli, for example, has written:[177]

“Again straps were fixed to the wrists of the dead, and they were dragged onto specially constructed chutes which unloaded them in front of the furnaces.”

The scene described is clearly false, because it shows the supposed gas chamber on the ground floor, in direct communication with the oven rooms. The area is well-known to have been located in the cellar (Kellergeschoss) of the crematorium, and Venezia himself speaks of the freight elevator used to transport the bodies from the supposed gas chamber to the oven rooms.[178]

Nevertheless, incredibly, neither Venezia, nor M. Pezzetti ever noted this grotesque architectural error.

Again, with reference to the transfer of bodies, Venezia adds:[179]

“In the drawing by David Olère, we see a corridor of water before the ovens which were used to transport the bodies more easily between the freight elevator and the ovens. We threw water into that rivulet and the bodies slid without too much effort.”

This “corridor of water” recalls the “wet slide” mentioned by M. Nyiszli. The drawing in question appears on the following page of the book[180]. For the moment, I will examine only the right-hand part of the drawing. I will discuss the left-hand part of the drawing, which shows the muffle-loading technique, later. To the right, therefore, we see the aperture of the freight elevator with an open double door.

A brief digression is necessary here. Venezia writes that “the freight elevators did not have any doors; a wall blocked one side and above the bodies were loaded from the other side.”[181] This description is not only in conflict with Olère’s drawing, but, even more seriously, with the design of the freight elevator installed in Crematorium III. This is design 5037 drawn by the Gustav Linse Spezialfabrik f.[ür] Aufzüge (manufacturer of special freight elevators) of Erfurt on 25 January 1943, bearing the heading “Lasten-Aufzug bis 750 kg Tragkraft für Zentralbauleitung der Waffen SS, Auschwitz/O.S.” (freight elevator up to 750 kg capacity for the Zentralbauleitung der Waffen SS, Auschwitz Upper Silesia).[182] This drawing shows that the freight elevator had a double door on both sides. One opened towards the oven room, the other towards the area designated “Waschraum und Aufbahrungsraum” of which I have already spoken.

Let us return to Olère’s drawing. Starting with the freight elevator, along the walls of the oven room with the windows, on the pavement, there ran a wet slide approximately a meter and half wide.[183] On top of this there are no bodies; a pile of bodies does appear instead between the slide and the ovens. In reality, this slide existed in Crematorium II. In the oven room, in front of each muffle, in the pavement, three pairs of rails were originally installed, linked to two oven-loading rails (Gleis zur Beschickung der Öfen), arranged perpendicularly to the first, right up to the freight elevator (Aufzug). Along the rails, there ran the corpse-insertion cart, which was called “Sarg-Einführungs-Vorrichtung,” a device for the introduction of the coffin. In March 1943, it was decided to replace this device with more practical “body stretchers” (Leichentragen).[184] The ruins of the oven room at Crematorium II still exhibit the rails located in front of the muffles; the loading rails which travelled to the freight elevator were, by contrast, torn up and the various grooves in which they were lodged mark out precisely a strip of concrete which appears to be a slide. In Crematorium III, it was decided, starting at the end of September 1942, to replace the body-loading cart with stretchers;[185] therefore no rails were installed in the oven room and there was no “slide” in front of the freight elevator.

Venezia’s narrative is also inspired by other drawings by Olère.

The tale of the victims who, unable to walk, were carried to the crematoria by truck and were thrown down by overturning the large dump truck “like sand, to be unloaded and they fell one on top of each other,”[186] is a simple comment on the related drawing by Olère, presented as “women selected in the camp, unloaded in front of Crematorium III.”[187]

The absurd story which, according to him, had been reported by several men from the “Sonderkommando”, according to which “in Crematorium V, the trucks unloaded the victims directly, while they were still alive, in the pits, which were burning under the open sky,”[188] similarly originates from two of Olère’s drawings, not published in Venezia’s book. These bear the following caption: “SS throwing live children in a burning pit (Bunker 2/V)”. The two drawings (the first and the draft of the second) show the rear part of a truck on the edge of a burning ‘cremation pit’; the large hopper, full of children, is tilting towards the pit and from the hopper an SS man, also on the edge of the pit, is grabbing the children and throwing them in; another soldier, also on the edge of the pit, salutes with a stiff arm. In reality, the two soldiers, because of the heat radiated by the bonfire, would have been burnt alive, while the gas tank of the truck would have exploded in a few minutes.

Venezia is referring to two Germans who were at the door of the gas chamber:[189] why precisely two? Because the related drawing by D. Olère shows—you guessed it—two Germans.[190]

The portrait of SS-Unterscharführer Johann Gorges[191] painted by D. Olère,[192] suggests the following description to Venezia:[193]

“Tall, with a broad face, but I can’t remember his name. He resembled one of the SS drawn by David Olère.”

The idea is taken from F. Müller, who describes “Gorges” physically, claiming that among other things he was tall (one meter eighty centimeters).[194]

The anecdote of the child found alive in the gas chamber, set forth by Venezia with a wealth of details, parties an example of the hyperdramatic fabrications characteristic of this type of literature, like that of the relatives whom one meets in the gas chamber.[195] For example, M. Nyiszli dedicates an entire chapter to this anecdote: in this tale, the victim in question is a girl.[196] Venezia refers, instead, to finding a girl two months old, alive, in the gas chamber.[197]

12. Crematory Furnaces and Cremation

Venezia provides no description of the oven room or the crematory ovens: he does not even say how many there were, much less how they were designed or how they worked.

The only thing he tells us in this regard is the loading of a muffle of an oven:[198]

“In front of each muffle, three men were busy putting the bodies into the oven. The bodies were arranged on a sort of stretcher, one for the head and one for the feet. Two men, on both sides of the stretcher, raised it with the help of a long piece of wood inserted from beneath. The third man, in front of the oven, pushed the handles and pushed the stretcher into the oven. He had to make the bodies slide inside, and then pull the stretcher away before the iron got too hot. The men from the Sonderkommando had gotten into the habit of pouring water on the stretcher before arranging the bodies on it, to keep them from sticking to the red-hot iron; otherwise the work would have become even more difficult: they had to detach the bodies with a fork and pieces of flesh remained stuck to the stretcher.”

This narrative is the result of an incautious fusion of the drawing by D. Olère which appears on the following page of his book, with an echo of the related tale by H. Tauber. The design is that which I have already examined in detail in relation with the supposed “wet slide,” which was located in the right-hand part of the drawing.[199] To the left, there appears precisely the scene of the three prisoners introducing the bodies into the central muffle of an oven with the Leichentrage. This scene can not correspond to reality.

First of all, the dimensions of the aperture of the muffle, and consequently of the ovens, are absolutely nonsensical. The apex of the vault of the door of the muffle by far exceeds the heads of the three prisoners, while in reality it was located only 132 centimeters from the floor.[200] If D. Olère had depicted the muffle with its real dimensions, he would not have been able to depict the scene of the simultaneous loading of three bodies. On the other hand, such a method of loading would also have impeded the combustion process: the bodies would have obstructed the apertures between the muffles through which the gases originating from the gas producers flowed from the side muffles into the central muffle, as well as the apertures in the grid of this same muffle, through which the burnt gases entered the underlying smoke conduit.

Secondly, the drawing shows flames and smoke issuing from the open muffle, which is impossible, because smoke and flames were immediately sucked away by the draft of the chimney, into the central muffle, all the more intensely since the apertures in the discharge conduit of the 3-muffle oven linked to the chimney were located precisely inside the central muffle, in the cinerary below. The door of the central muffle opened to the right: as a result, the prisoner shown to the right, raising the stretcher, would have been standing in front of the inner side of the door, which had a working temperature of 800°C. This prisoner, who, like his two companions, appears with a naked torso, would have suffered fatal burns from the heat of the cast-iron door.

Moreover, the loading technique described in the drawing is also erroneous. The 3-muffle oven was equipped with two rollers (Laufrollen), attached to a tip-up frame pivoting on a round attachment iron (Befestigungs-Eisen) welded to the anchor bars of the oven underneath the doors of the muffle. These rollers served initially for the sliding into the muffle of the loading beam of the body-introduction cart, later for the sliding of the Leichentrage, whose lateral tubes, as long as the rollers, were supported precisely on top of the rollers, to permit the stretcher to slide inside the muffle. This is precisely what Tauber reports, who however adds that the operation was performed by six prisoners, not by three. The technique described in the drawing by Olère would have required at any rate at least four prisoners, since the prisoner assigned to the stretcher would not have been able, all by himself, to “cause the bodies to slide in” onto the refractory grid of the muffle. This as Tauber says, was the task of another prisoner, who had to hold the bodies in place with a scraper while the stretcher was being extracted from the muffle.[201]

The rollers permitted the two prisoners raising the stretcher with an iron bar (not with “a piece of wood,” as Venezia carelessly assumes from the drawing by D. Olère) to remain at a safe distance from the open door of the muffle, preventing them from burning themselves.

The most surprising thing is that D. Olère, in the fifth 3-muffle crematory oven, has correctly drawn both the attachment bar, and the rollers!

Venezia, finally, freely inspired by Tauber’s account, has forgotten to state that the water poured onto the stretcher had to be soapred:

“They melted soap in the water, so that the bodies slid better on the stretcher.”[202]

Let’s go on to the essential question of the cremation capacity of the ovens.

In his first statement, Venezia affirmed in this regard:[203]

“After these operations the bodies were thrown on freight elevators, which carried them to the ground floor where the crematory ovens were. There other prisoners inserted them into the ovens, two or three at a time. After 20 minutes, only ashes and pieces of the largest bones remained.”

This information – 3 bodies in 15 muffles in 20 minutes for 24 hours – is taken from the testimony of M. Nyiszli:[204]

“There they were laid out in threes on a kind of pushcart made of sheet metal. […] The bodies were cremated in twenty minutes.”

This corresponds to a theoretical maximum crematory capacity of (3 x 15 x 24 x 60 ÷ 20 =) 3,240 bodies in 24 hours.

In open contradiction to the above, in the interview published by Il Giornale and by Gente, Shlomo Venezia declared:[205]

“[Question] How many hours a day did the ovens function?

[Venezia] 24 hours a day. We worked shifts from 8 in the morning to 10 at night, or from 10 at night to 8 in the morning. We cremated 550-600 Jews a day.”

Therefore, the maximum crematory capacity of the ovens of Crematorium III was 600 bodies per 24 hours; the difference between 600 and 3,240 is not trivial. Venezia also claims:[206]

“The gas chamber had a capacity of approximately 1,400 persons, but the Nazis succeeded in cramming in 1,700.”

So that to cremate one load of gassing victims took (1,700 ÷ 600 =) almost 3 days (in reality almost 6 days), and he has also clearly stated:[207]

“On average, the entire process of elimination of a convoy lasted 72 hours. Killing them was quick, but burning the bodies took longer: there was not a minute to rest.”

He has thus confirmed the maximum cremation capacity of 600 bodies in 24 hours. But in his book, Venezia writes:[208]

“Crematoria IV and V were smaller than Crematoria II and III; the ovens didn’t work as well and had less capacity. The pits permitted us to accelerate the pace of the work: burning seven hundred bodies in such small ovens was a long operation, all the more so because the ovens did not function correctly. Where we were, by contrast, we could cremate up to one thousand eight hundred persons.”

The crematory capacity of a typical II/III crematorium adopted by the witness, therefore, before rises from 3,240 to 550-600 and then falls to 1,800 bodies in 24 hours, without any explanation.

At this point, it is interesting to read the testimony of Venezia’s fellow unfortunates. His cousin Y. Gabai claimed that they loaded four bodies in every muffle (vier Leichen), which burned completely in half an hour, so that the capacity of Crematorium III was (4 x 15 x 24 x 60 ÷ 30 =) 2,880 bodies in 24 hours.[209]

J. Sackar stated:

“In the oven, the fire [sic] was so hot that the bodies burned immediately [sofort] and we could introduce other bodies continually”.

This fantastic immediate cremation meant that, in all the crematoria at Birkenau, it was possible to cremate “almost 20,000 men [sic] a day”![210]

The capacity pertaining to Crematorium III, considering that the total number of muffles was 46, 15 of which were located in this crematorium, amounted to ([20.000 ÷ 46] x 15) approximately 6,500 bodies in 24 hours.

S. Chasan affirms on the other hand that in every muffle they loaded “between two and five bodies,” and that the cremation lasted half an hour, so that “every half hour we could cremate from 50 to 75 bodies,” or, rather, at a maximum, precisely (75 ÷ 15 =) 5 bodies per muffle. This means 150 bodies in one hour and 3,600 in 24 hours.

Let’s summarize the statements of the witnesses on this crucial aspect of the supposed extermination process in the following table:

| Witness | Cremation Capacity |

|---|---|

| Venezia 1 | 3,240 |

| Venezia 2 | 550-600 |

| Venezia 3 | 1,800 |

| Gabai | 2,880 |

| Sackar | 6,500 |

| Chasan | 3,600 |

There is no need to recall that the witnesses were referring to the same installations over the same period.

Nevertheless, over the course of the interrogations to which they were subjected by the Soviet counterespionage service, the Topf engineers Kurt Prüfer and Karl Schultze, who had designed the 3-muffle oven and the blower, respectively, both declared that the cremation of one single body in one muffle required one hour[211] and that this was precisely the effective capacity shown by other equivalent technical sources.[212] Therefore, the maximum theoretical crematory capacity of the model II/III crematorium was (15 x 24 =) 360 bodies in 24 hours. I say “theoretical,” because the crematory ovens could not function continually 24 hours a day, as I will soon explain.