The Violinist

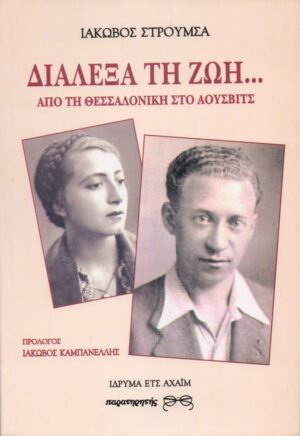

Jacques Stroumsa, Geiger in Auschwitz: ein jüdisches Überlebensschicksal aus Saloniki, 1941-1967, Hartung-Gorre, Konstanz, 1993; Violinist in Auschwitz: from Salonica to Jerusalem, 1913-1967, ibid., 1996; Διαλεξα τη ζωη: Απο τη Θεσσαλονικη στο Αουσβιτς, Parateretés, Thessaloniki 1997.

Do you ever go to concerts? Meet Jacob (Jacques) Stroumsa, the violinist of Auschwitz. Stroumsa was an electrical engineer and an amateur violinist. He arrived at Birkenau on May 8, 1943. After spending one month in the camp orchestra, he was transferred to Auschwitz where, after some gardening duties, he managed to find a job fitting his expertise: in a metal factory. In January 1945 he was sent to Mauthausen on a “death march,” then to Gusen, then back to Mauthausen, then Gusen II where he was liberated by the Americans on May 8, 1945. After the war, he lived in Paris before emigrating to Israel in 1967.

His German(!) memoir Geiger in Auschwitz was published in 1993, in English in 1996, and in Greek in 1997 under the title I Chose Life. Let’s see what we can find in it that either supports or undermines the orthodox narrative.

Where Did they Go?

As with other witnesses, Stroumsa never actually saw any extermination of prisoners. On his first day at Birkenau, after a first questioning from an officer regarding his age, skills etc., he was sent to another room for a medical examination. There he found a doctor who was a friend of his from Thessaloniki. The doctor told him:

“Right now, your parents, your wife and her parents have already been gassed in a gas chamber, and then they will burn them in the crematorium furnaces. The young have a small chance of staying alive, if they don’t get sick. They will have to work, each according to his expertise, until the end of the war.” (p. 46)

At first, Stroumsa thought he was crazy and delirious. But in the end, that was it. Stroumsa believed that those unfit for work were gassed. He writes about his cousin:

“He was sick. The cause was a hangnail on his finger that had festered. Jacques was at the Revier, the camp hospital, and there, in a Selektion, that is selection, they took him for the gasses.” (p. 14)

But as he clearly states (p. 145), the only thing he ever actually saw was the chimneys of the crematoria.

At the Hospital

After his transfer to Auschwitz, Stroumsa felt during one night a sharp pain in his lower abdomen. He went to the hospital, where an SS doctor diagnosed a hernia and ordered surgery. Stroumsa was trembling with fear and could not sleep at night. On the next day he was in the surgery room. They told him not to be afraid as they would administer a local anesthetic. After the injection, they tied him to the table. As he was lying there watching everything he wondered:

“I could not understand the mindset of our executioners. On the one hand they beat, killed, sent anyone to the gas chamber for the most trivial reasons, like for example a hangnail on the finger. And on the other hand they had orchestra, a hospital with a real surgical room, they gave you anesthesia so that you would not suffer, intending to cure a hernia and be useful to them again for work. All this seemed unbelievable!” (p. 62)

This is very important. The prisoners were so convinced about things they had not seen that they had trouble believing what they actually did see.

The Trial

Here’s another “unbelievable” incident. Stroumsa had made friends at work with a Polish Catholic. One night, the Pole invited him to his house when the war would be over. He gave him his address on a piece of paper. But when later an SS technician searched him and found the paper, the SS men accused him of planning to escape. Stroumsa was immediately locked up in Block 11, and two days later he was put on trial.

First, the SS judge asked him politely whether he would like to have an interpreter. Stroumsa, being quite familiar with German, declined. He answered calmly all their questions. Here’s what followed:

“Then, an unbelievable thing, the court, after consultation, set me free and sent me back to work, in fact they also gave me a day off.” (p. 79)

Many years later, in the book Secretaries of Death by Lore Shelley,[1] Stroumsa found out, along with some biographical information, who the SS judge was: SS Unterscharführer Klaus Dylewski.

“Dylewski was responsible for the murder of prisoners at Block 11, and also took part at the ‘selektion’ at the train platform. He was arrested on April 1959 and sentenced to imprisonment by the Frankfurt court. But he saved my life by sending me back to my work.” (p. 80)

What about the Gas Chambers?

In the main text of the book, Stroumsa does not give any information on the gas chambers. Only in the appendix does he give the testimony of a friend, Hazan Saul, who claims to have worked in the Sonderkommando. Starting on page 143, we read the following:

“When the Jews disembarked from the train, after the first selection, they took those soon to die into the gas room, which could take in around 3,000 people. Inside along the walls there were benches, and above them hangers, and above each hanger a number. They were told to undress and hang their clothes, and remember the number where each had hung his things. In the ceiling they could see the shower heads, in order to have the illusion that soon water would come out. As soon as the room was full, the doors were hermetically closed. An SS man came on a motorcycle bringing two cans of Cyclon. He put on a mask, opened the cans, and poured the content through two openings. One or two skylights allowed him to see into the room to observe the procedure that lasted around half an hour. Finally, they opened the door and turned on special fans to remove the poisonous gasses.”

Here we have some common contradictions to the orthodox narrative. The facility described closely resembles Crematoria II & III, but there, Zyklon was allegedly not poured directly into the chamber but into some contraptions; it allegedly had not two but four openings through which Zyklon B was poured, and observation is said to have occurred through a peephole in the door, not through non-existing skylights. Furthermore, the story contains two physical impossibilities: 3,000 people cannot fit into a space of some 210 m², and ventilation would have had to occur for an extended period of time long before the door could have been opened. But the most egregious mistake in this description is that it seems to imply that the undressing room and the gas chamber were one and the same room.

As for the crematoria, no details are given. There is only the much-repeated fairy tale of trucks unloading sick prisoners directly into fiery pits, as the crematoria allegedly could not keep up (p. 143).

Summary

The witness is certainly credible. His doctor friend had told him that there was a chance of surviving if you didn’t get sick, but his experience proves otherwise. His trial also delivers a heavy blow to the portrayal of the SS as bloodthirsty monsters who tortured and killed prisoners for fun. And once again there is no first-hand knowledge of mass killings. Once more, it is quite an irony that testimonies offered in favor of the extermination thesis turn out to support the revisionist viewpoint.

Notes

| [1] | Lore Shelley, Secretaries of Death: Accounts by Former Prisoners Who Worked in the Gestapo of Auschwitz, Shengold, New York 1986. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, Vol. 10, No. 1 (winter 2018)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a