What Causes Anti-Semitism?

An Important New Look at the Persistent 'Jewish Question'

Separation and its Discontents: Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism, by Kevin MacDonald. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1998. 325 pages. Source references. Bibliography. Index. $65.00. [Available for sale from the IHR]

Peter Harrison is the pen name of an East Coast businessman with a keen interest in history who has traveled widely in Europe and Asia.

Of all the taboos in American society, none is more powerful than that which limits public discussion about Jews. Though they are only three percent of the population, Jews playa disproportionately powerful – and sometimes decisive – role in the cultural and political affairs of the United States. Jews are so powerful, in fact, that they have been largely successful in suppressing public discussion of their power. As Joseph Sobran once observed, any American writer who begins to describe the extent of Jewish influence quickly gets the message: you must pretend that we are powerless victims, and if you don't respect our victimhood, we'll destroy you.

Even within this great taboo, some subjects are more taboo than others, and Kevin MacDonald, a professor of psychology at California State University at Long Beach, has just published a remarkable volume that tackles head-on what may be the most diligently suppressed question of our time: Why do people hate Jews?

In contrast to the generally available treatments of this issue, MacDonald has produced a study of rare, even shocking forthrightness and scope. One would have to go back at least 50 years to find anything comparable to this extraordinary work. It is serious, exhaustively researched, and relentlessly factual. Given the prevailing structure of taboos, it is pure nitroglycerin.

Separation and its Discontents is the second of a three-volume study issued by Praeger, a leading American academic publisher, that explores Jewish behavior as a “group evolutionary strategy.” In the first volume, A People That Shall Dwell Alone (published in 1994), MacDonald establishes the intellectual framework for his analysis. Judaism, he argues, is a collective strategy for group survival based on religious teachings that emphasize genetic and cultural separation from others, and an explicit double standard of morality – altruism and cooperation among Jews, but competition with gentiles (non-Jews). Fierce devotion to the group, combined with religious prohibitions against intermarriage have preserved the integrity of Jewish peoplehood despite a history that would have dissolved most other tribal allegiances. In competition with other groups, loyalty and subordination to the group provide a decisive evolutionary advantage. Even small numbers of group-oriented Jews, acting together, can exert considerable influence over the loosely-organized non-Jewish populations among-whom they live.

Jews have, however, paid a price for their extraordinary capacity for group survival. The volume under review here is a study of how non-Jews have responded to distinctly Jewish patterns of behavior. MacDonald persuasively argues that most of what is called “anti-Semitism” is an entirely understandable reaction to Jewish group activities that compete directly with non-Jews. Hostility toward Jews in Western societies has closely mirrored Jewish behavior. Gentiles who ordinarily have only loose group loyalties react to the intense, “ingroup-outgroup” consciousness of Jews by forming their own authoritarian, group-oriented structures in order to compete with Jews.

A People Apart

Today it is essentially obligatory to describe anti-Semitism as irrational hatred for an unoffending people, but MacDonald argues that anti-Jewish sentiment has been too persistent and widespread to be so easily dismissed: “The remarkable thing about anti-Semitism is that there is an overwhelming similarity in the complaints made about Jews in different places and over very long stretches of historical time.” Moreover, antipathy toward Jews does not arise only in certain kinds of societies, but rather seems to be a nearly universal phenomenon: ''There is evidence for anti-Semitism in a very wide range of both Western and non-Western societies, in Christian and non-Christian societies, and in precapitalist, capitalist, and socialist societies.”

To what, then, is anti-Semitism a reaction? One of the most salient Jewish characteristics, Mac-Donald shows, has been a group identification so strong that it implies the insignificance of non-Jews: “At the extreme, when there is very powerful commitment to the Jewish ingroup, the world becomes divided into two groups, Jews and gentiles, with the latter becoming a homogenized mass with no defining features at all except that they are non-Jews.”

Even the ancients noted a strong sense of cohesion among Jews. “See how unanimously they stick together, how influential they are in politics,” wrote the Roman statesman Cicero. Under the Romans, Jewish group behavior was a constant source of conflict. Although the government of Rome generally protected the Jews from repeated outbursts of popular hostility throughout the empire, the Jews never reconciled themselves to Roman rule. No other subject people of the Roman empire, MacDonald writes, “engaged in prolonged, even suicidal wars against the government in order to attain national sovereignty;”

In the Middle Ages Jews showed a similarly fanatic group loyalty. During the first Crusade when, faced with the grim choice of conversion to Christianity or death, they readily chose to die en masse. Men killed their wives and children and then offered their own necks to the sword rather than betray their heritage. “Such examples,” writes MacDonald, “suggest that there are no conceivable circumstances that would cause such people to abandon the group … ” Nor, he argues, has such fanaticism completely disappeared. He cites the 1997 case of an American Jew who killed his two children because his ex-wife intended to rear them as Christians.

In keeping with current findings on the substantial heritability of personality traits, MacDonald cites evidence to show that the strong Jewish group orientation has a biological basis. Historically, Jews who have not clung to the group, or have not been willing to sacrifice for it, have defected or been expelled, meaning that those who remained had a firmly collective orientation. This helps explain why Jews are over-represented today in religious cults, and that many cultists come from non-religious Jewish families. MacDonald suggests that cults may answer the need for group affiliation for Jews who have slipped out of the orbit of Judaism.

President Clinton with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu at a White House news conference in February 1997. On this occasion, the Zionist leader praised Clinton as “an exceptional friend of Israel.” As Prof. MacDonald explains in Separation and its Discontents, throughout history Jewish leaders have been adept at making strategic alliances with non-Jewish political figures to further Jewish group interests.

Members of every ethnic, racial, national and religious group like to think well of themselves. While a positive self-image is normal among all peoples, it is pronouncedly true of Jews, who have long regarded themselves as a superior people. MacDonald quotes Nahum Goldmann, former president of the World Jewish Congress, about the attitude of Jews in early 20th century Lithuania toward the non-Jews amongst whom they lived: “Every Jew felt ten or a hundred times the superior of these lowly tillers of the soil.” Feelings of this kind, MacDonald notes, are mandated by the Talmud and other Jewish religious writings. Similarly, the great Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides described gentiles as unclean and unworthy of the treatment reserved for fellow Jews. It was therefore typical of ghetto Jews to call a stupid Jew a goyisher kop, or gentile head. MacDonald argues that even today, the idea that Jews are a morally superior “chosen people” is a central feature of Jewish identity. Gentiles have not failed to notice and resent this attitude.

Another universal complaint about Jews has been that they are more loyal to their own people than to the nation in which they live, that they constitute”a nation within a nation.” While many Jews have deceitfully denied such parochial loyalties, others have proclaimed them openly. MacDonald quotes Stephen Wise, president during the 1930s of the American Jewish Congress: “I am not an American citizen of the Jewish faith, I am a Jew.” And further: “I have been an American for 63/64ths of my life, but I have been a Jew for four thousand years.” Harvard Sociologist Daniel Bell writes of “the outward life of an American and the inward secret of the Jew. I walk with this sign as a frontlet between my eyes, and it is as visible to some secret others as their sign is to me.”

Theodor Herzl, the founder of the modern Zionist movement, believed that hostility toward Jews was a natural reaction to Jewish behavior. “I find the anti-Semites are fully within their rights,” he wrote. This 1960 Israeli postage stamp honors Herzl and his work.

Minorities that hold themselves aloof are usually disliked. In Europe, the unpopularity of Jews was compounded by their choice of professions. Jews were middlemen and merchants, often disdaining the hard physical labor done by gentile commoners. Because Christians were forbidden to lend at interest, Jews monopolized the money-lending trade, and during the Middle Ages charged annual rates of 20 to 40 percent. MacDonald notes that part of this profit was handed over to kings and aristocrats in taxes, and that it was common for Jews to make alliances with gentile elites.

Another common Jewish profession was that of tax farmers – that is, they “paid a fixed sum to the nobility for the right to obtain as much in taxes as they could from the Christian population.” Jews were “ideal tax farmers” because they “could be trusted to treat the gentiles as an outgroup and maximize the king's revenues.” Because they did not think of themselves as part of the nation, they had fewer scruples about extracting even the most painful taxes. Jews were known for sharp practice, and accordingly were often resented by the common people, but the gentile nobility, which found them useful, frequently protected them against uprisings.

Jews are smart. As MacDonald notes, Jews score, on average, a full standard deviation higher than Caucasian gentiles on intelligence tests, and he attributes this higher intelligence primarily to genetic differences. Jews have therefore been very successful in their chosen fields. However, he goes on, “the success of these pursuits and the fact that these pursuits inevitably conflict with the interests of groups of gentiles (or at least are perceived to conflict with them) is, in the broadest sense, the most important source of anti-Semitism.”

Assimilation and Expulsion

Over the centuries, host nations have taken various approaches toward this group that refused to fully assimilate. Throughout Christendom the authorities tried to convert Jews, sometimes forcibly, and when this failed they often expelled them. The French experience, MacDonald writes, was typical:

In 12th-13th-century France there was a shift from a policy of toleration combined with attempts to convert Jews under Louis IX to a policy of “convert or depart” during the reign of Philip IV, and finally the expulsion of Jews in 1306. The final expulsion order is also a last plea for Jewish assimilation: “Every Jew must leave my land, taking none of his possessions with him; or, let him choose a new God for himself, and we will become One People.” [Italics in the original]

Spain, to which MacDonald devotes considerable attention, proceeded to forcible conversions in 1391 and then to expulsion in 1492. However, many converts, or “New Christians” as they were called, continued to socialize and marry only among themselves, and to cooperate professionally with each other, so conversion had little effect on group behavior. This was a major reason for the Inquisition. But, as MacDonald points out, Jews in Spain were persecuted not for who t~ey were but for what they did:

The real crime in the eyes of the Iberians was that the Jews who had converted in 1391 were racialists in disguise, and this was the case even if they sincerely believed in Christianity while nevertheless continuing to marry endogamously and to engage in political and economic cooperation within the group … It was not the extent of Jewish ancestry that was a crime, but the intentional involvement in a group evolutionary strategy.

Those New Christians who abandoned parochial loyalties and embraced the Spanish nation along with the Christian faith had little to fear from the Inquisition.

In later periods, when European Jews were emancipated from the myriad restrictions of the . ghetto, host countries expected Jews to assimilate completely. Instead, they soon faced the same dilemma as had the Spanish. As one Jewish historian writes, “Jewish Emancipation had been tacitly tied to an illusory expectation – the disappearance of the Jewish community of its own volition. When this failed to happen … a certain uneasiness, not to say a sense of outright scandal, was experienced by Gentiles.” Far from wholly embracing the larger society, many Jews continued to marry only among themselves, and to consider themselves a people apart. Rather than promote intermarriage, some zealous Jews advocated Zionism (Jewish nationalism) as a modern and non-religious means of keeping Jews apart from Gentiles.

Many Jews recognized that such strong particularism was not acceptable to gentiles. Theodor Herzl, the main founder of modern political Zionism, regarded anti-Semitism as “an understandable reaction to Jewish defects … ” “I find the anti-Semites are fully within their rights,” he also wrote.

Similarly, Chaim Weizmann, for decades an important Zionist leader and Israel's first president, observed:

Whenever the quantity of Jews in any country reaches the saturation point, that country reacts against them … [This] reaction … cannot be looked upon as anti-Semitism in the ordinary or vulgar sense of that world; it is a universal social and economic concomitant of Jewish immigration and we cannot shake it off

MacDonald argues that it is this refusal to assimilate, even on terms of equality, while at the same time pushing a separate agenda, that finally leads to the harshest extremes of anti-Semitism:

A related common thread [in the European experience with Jews] has been that there is a tendency to shift away from attempts at complete cultural and genetic assimilation of Jews in the early stages of group conflict, followed eventually by the rise of collectivist, authoritarian anti-Semitic group strategies aimed at exclusion, expulsion, or genocide when it is clear that efforts at assimilation have failed.

MacDonald finds it significant that European nations have almost invariably proposed complete cultural and biological assimilation, but that it is Jews who have rejected this. “The fact that Western societies have typically attempted to convert and assimilate Jews before excluding them indicates that Western societies, unlike the prototypical Jewish cultures, do not have a primitive concern with racial purity.” MacDonald argues that Western societies are, by nature, individualistic rather than group-oriented, and that this is the perfect environment for any “outgroup” that pursues a collective strategy. By acting in concert, Jews can successfully advance particularist interests that may conflict with those of the host population.

In comparison to the West, Jews have found it much more difficult to penetrate Muslim societies:

One prominent Jewish historian, Louis Namier, has gone so far as to say that there is no Jewish history, “only a Jewish martyrology.”

“These 'segmentary' societies organized around discrete groups appear to be much more efficient than Western individualistic societies in keeping Jews in a powerless position … “

Christianity and National Socialism

It is in the context of his characterization of Western societies that MacDonald makes some of his most arresting arguments: “The individualism typical of Western societies is an ideal environment for Judaism as a cohesive group strategy, but as Jews become increasingly successful politically, economically and demographically, Western societies have tended to develop collectivist group structures directed at Jews as a hated outgroup.” In other words, the group activities of Jews can become so successful and threatening that the larger society adopts collective, anti-Jewish responses that imitate Jewish behaviors. The two most striking examples described by MacDonald are Christianity and National Socialism.

In what may be one of his most surprising arguments, MacDonald contends that the authoritarian structure and cohesiveness of the early Christian church (second to fifth centuries) was a reaction to the cohesiveness of Judaism:

The entire thrust of the [church-supported] legislation that emerged during this period was to erect walls of separation between Jews and gentiles, to solidify the gentile group, and to make all gentiles aware of who the “enemy” was. Whereas these walls had been established and maintained previously only by Jews, in this new period of intergroup conflict the gentiles were raising walls between themselves and Jews.

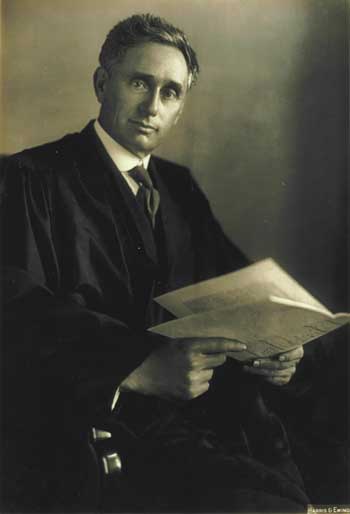

Louis Brandeis, a prominent Jewish community leader and the first Jew to be appointed to the US Supreme Court, said that “to be good Americans we must be better Jews; to be better Jews we must be Zionists.”

The leading figures in shaping the early Church – Augustine, Ambrose, Jerome, Chrysostom, Cyril – were ferocious anti-Semites whose hostility toward Jews reflected the nearly universal attitude of early Christians. These early Church fathers, MacDonald further notes, did not attempt to convert Jews, but regarded them as members of an essentially alien group against whom Christians should define themselves, just as Jews defined themselves in contrast to gentiles. He notes that Constantine the Great, the emperor who in 313 issued the edict legalizing Christianity throughout the empire, was so hostile to Jewish power and influence that a good case can be made that his Christianity, at least in part, was a means of promoting anti-Jewish policies.

German National Socialism, MacDonald contends, “is a true mirror-image of Judaism. Not surprisingly it was also the most dangerous enemy that Judaism has confronted in its entire history.” Although Christianity may have established group cohesiveness in response to Jewish solidarity, its theology pushed it toward universalism and even pacifism.

Hitler's militant movement, on the other hand, had no such constraints, and therefore, MacDonald contends, had more in common with Jewish particularism:

As in the case of Judaism, there was a strong emphasis [by the National Socialists] on racial purity and on the primacy of group ethnic interests rather than individual interests. Like the Jews, the National Socialists were greatly concerned with eugenics. Like the Jews, there was a powerful concern with socializing group members into accepting group goals and with the importance of within-group altruism and cooperation in attaining these goals.

Houston Stewart Chamberlain, an intellectual forebear of National Socialism, wrote explicitly that the extraordinary ability of Jews to maintain racial distinctiveness and historical continuity was something to both fear and to imitate.

The Hitler Youth organization, MacDonald points out, was very successful in fostering in young Germans a fervent sense of identity with and loyalty to the (national) group. The ardent group identification promoted by National Socialism, MacDonald argues, deviated from traditional Western individualism, and bears unmistakable features of Judaism.

Some Jews recognized and applauded these similarities. Joachim Prinz, a German-born rabbi who later became head of the American Jewish Congress, wrote of Hitlerite Germany:

A state built upon the principle of the purity of nation and race can only be honored and respected by a Jew who declares his belonging to his own kind … For only he who honors his own breed and his own blood can have an attitude of honor toward the national will of other nations. [Italics in the original]

In MacDonald's view, the Third Reich emphasis on race, group, loyalty, and devotion was a deviation from the Western tradition of individualism. In order to compete with Jews, Germans had to become more like Jews and less like Germans. This drastic response to Jewish behavior, MacDonald contends, is part of a predictable pattern:

While Judaism flourishes in a classical liberal, individualist society, ultimately Judaism is incompatible with such a society, because it unleashes powerful group-based competitions for resources within the society, which in turn leads to highly collectivist gentile movements incompatible with individualism.

MacDonald's view that the presence of Jews turns Europeans away from their own social and cultural heritage is indeed provocative – and he promises to flesh it out inA Culture o{Critique, the forthcoming final part of his three-volume study.

Deception and Self-Deception

Jews have developed highly sophisticated methods to combat the resistance they have everywhere encountered. MacDonald categorizes these methods as either deception or self-deception, the purposes of which are to conceal Jewish particularity and the extent to which Jewish objectives may conflict with those of others. One of the most common Jewish deceptions, he notes, is to pretend (at least to nonJews) that Jews constitute merely a religious group. Accordingly, Jewish leaders often denounce anti-Semitism as a form of religious bigotry.

In fact, MacDonald points out, Jewry has always had important characteristics of a race or nation. He quotes one Jewish historian who frankly acknowledges: ''The definition of the Jewish community as a purely religious unit was, of course, a sham from the time of its conception.” Another Jewish author on Germany in the early 20th century stated: “Liberal laymen … were in the mass irreversibly secularized Jews, who called themselves religious principally to escape suspicion that their Judaism might be national.” Or as Stephen Wise bluntly put it: “Hitler was right in one thing. He calls the Jewish people a race and we are a race.”

In this regard, MacDonald notes a long tradition of Jewish conversions to Christianity that were merely tactical deceptions. He quotes the German poet Heinrich Heine, who was baptized but later in life wrote,”I make no secret of my Judaism, to which I have not returned, because I have not left it.”

Another common Jewish deception is to conceal the true nature of Jewish thought. For example, Jewish authorities sometimes remove anti-gentile passages from translations of classic Hebrew texts. In Israel, where there is no fear of persecution, these texts are published intact. Likewise, Jews generally prefer that gentiles be unaware of internal Jewish debates. MacDonald quotes two German Reform rabbis from the early 20th century: “As long as the Zionists wrote in Hebrew, they were not dangerous. Now that they write in German it is necessary to oppose them.”

Yet another common Jewish deception is to hide Jewish influence and interests by giving them a gentile appearance. Thus, MacDonald notes, when the New York Civil Liberties Union challenged prayer in New York schools it camouflaged the primarily Jewish interest in the issue by having its one non-Jewish lawyer argue the case in public.

Jewish Communists have long tried to hide the tremendous role played by Jews in MarxismLeninism. As MacDonald notes: “CPUSA [Communist Party USA] leaders were greatly concerned that the party image was too Jewish, with the result that Jewish members were encouraged to adopt non-Jewish-sounding names, and there were active (largely unsuccessful) efforts to recruit gentile members.”

“A multicultural society in which Jews are simply one of many tolerated groups is likely to meet Jewish interests, because there is a diffusion of power among a variety of groups and it becomes impossible to develop homogeneous gentile ingroups arrayed against Jews as a highly conspicuous outgroup.”

Although Jews have worked consciously to advance their own group political interests, they have routinely tried to give the impression that they have no interests that differ from those of the larger society. MacDonald notes, for example, the forceful efforts of European and American Jews in the 19th and early 20th centuries to topple the Tsarist regime in Russia. This campaign, which was really motivated by concern for the well being of fellow Jews in the Russian empire, was contrary to the interests of the United States and the western Europe states, which supported the Tsar, or least benefited from stable relations with Russia's ardently Christian regime.

Another example is the deceitful, ceaseless public-relations effort by Jewish organizations (and their non-Jewish political allies in the mass media and the two major parties) to portray United States support for Israel as somehow beneficial to American interests.

Double Standard

A good example of Jewish self-deception, MacDonald writes, is the persistent unwillingness of Jews to acknowledge any contradiction in preaching universalistic equality for others while maintaining an exclusivist group identity for themselves. Jews have commonly thought of themselves as “a light unto the nations,” whose historic role is to instruct other peoples in universal moral principles. In recent years one of the most conspicuous of these principles is that distinctions among nations, peoples, races, and cultures are artificial, and that to insist on such distinctions is immoral. As MacDonald points out, Jews act as if this is a principle that applies only to others. He goes on to explain how this double standard serves Jewish interests:

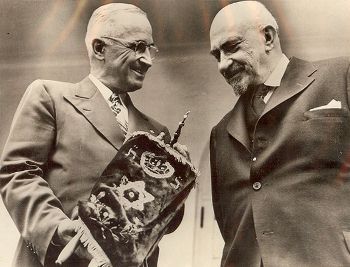

President Harry Truman welcomes Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann, who served as Israel's first president, to the White House, May 1948. As Prof. MacDonald notes in “Separation and its Discontents,” Jewish groups pressured Truman into authorizing United States support for Zionist ambitions in Palestine. He decided to recognize the new state of Israel against the advice of his most trusted counselors, who warned that such support would have dangerous long-term consequences. Truman himself commented: “I do not think I ever had so much pressure and propaganda aimed at the White House as I had in this instance.”

At the extreme, the acceptance of a universalist ideology by gentiles would result in their not perceiving Jews as in a different social category at all, while nevertheless Jews would be able to maintain a strong personal identity as Jews.

Typical of the way Jews like to regard themselves is this self-flattering description by Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis:

I find Jews possessed of those very qualities which we of the twentieth century seek to develop in our struggle for justice and democracy; a deep moral feeling which makes them capable of noble acts, a deep sense of the brotherhood of man; and a high intelligence, the fruit of three thousand years of civilization. These experiences have made me feel that the Jewish people have something which should be saved for the world …

Brandeis goes on to note: “to be good Americans we must be better Jews; to be better Jews we must be Zionists.”

Sentiments of this kind, MacDonald contends, are either an attempt to deceive others or examples of self-deception. Brandeis is urging Jews to become better Americans by asserting a non-American identity-something he would never suggest to any other ethnic group. Presumably, this is legitimate because Zionism will preserve for the world the desirable qualities Brandeis has discovered in his own people. As MacDonald notes, “Jews must retain their distinctiveness from the surrounding culture in order to fulfill their destiny to humanize and civilize all of humanity” – this, despite, the fact that part of their civilizing mission is the obliteration of distinctions among peoples.

This Jewish strategy of breaking down cultural, ethnic, racial and religious distinctions among nonJews while fostering a high level of Jewish particularism has an understandable goal, MacDonald explains:

A multicultural society in which Jews are simply one of many tolerated groups is likely to meet Jewish interests, because there is a diffusion of power among a variety of groups and it becomes impossible to develop homogeneous gentile ingroups arrayed against Jews as a highly conspicuous outgroup.

In other words, Jews are most successful when they operate among “tolerant” populations with a feeble sense of racial, ethnic, cultural or religious self-awareness.

Victimhood Mentality

Persecution and victimhood have long been central features of Jewish self-identity, MacDonald contends: “Jewish religious consciousness centers to a remarkable extent around the memory of persecution. Persecution is a central theme of the holidays of Passover, Hanukkah, Purim, and Yom Kippur.” One prominent Jewish historian, Louis Namier, has gone so far as to say that there is no Jewish history, “only a Jewish martyrology.”

MacDonald cites the words of the influential American Jewish writer Michael Lerner, who points out that such leading American Jewish groups as t he Anti-Defamation League and the Simon Wiesenthal Center have built their financial appeal to Jews on their “ability to portray the Jewish people as surrounded by enemies who are on the verge on launching threatening anti-Semitic campaigns.” These organizations, Lerner goes on, have “a professional stake in exaggerating the dangers …”

An important feature of the Jewish pattern of self-deception, MacDonald explains, is to exaggerate anti-Jewish sentiment in order to bolster Jewish group identity and cohesion. According to a 1985 survey, one third of San Francisco-area Jews expressed the view that anti-Semitism was so widespread that a Jew could not be elected to Congress – even though at the time three of the four area congressional representatives were well-identified Jews, as were both state senators and the mayor of San Francisco.

In recent decades, the “Holocaust” has come to playa primary role in fostering the “eternal victim” self-identity. Citing works by the Jewish scholars Michael Wolffsohn and Jacob Neusner, MacDonald notes that Jewish leaders work “with great success to use awareness of the Holocaust to intensify Jewish commitment, to the point that the Holocaust rather than religion has become the main focus of modem Jewish identity and the principallegitimator of Israel.”

So successful has this campaign been that according to a recent survey, 85 percent of American Jews say that the Holocaust is “very important” to their sense of being Jewish – a higher figure than the percentage of those who say that God, the Torah, or the state of Israel are “very important.” Jewish historian Zygmunt Bauman, MacDonald also notes, has pointed out that Israel uses the Holocaust “as a certificate of its political legitimacy, as safe-conduct pass for its past and future policies, and, above all, for advance payment for the injustices it might itself commit.”

Promoting Jewish Interests

“In all historical eras,” MacDonald observes, “Jews as a group have been highly organized, highly intelligent, and politically astute, and they have been able to command a high level of financial, political and intellectual resources in pursuing their group goals.” Jews have wielded their great power and influence, he goes on to note, “in establishing and maintaining governments that promote Jewish interests … This Jewish influence is often obtained by financial contributions, manipulation of public opinion via control of the media, and political activism … “

In this regard MacDonald notes that “another Jewish media interest has been to promote positive portrayals of Jews and combat negative images.” Major Jewish organizations, he goes on to report, quietly developed a “formal liaison with the [Hollywood] studios by which depictions of Jews would be subjected to censorship” and “scripts were altered to provide more positive portrayals of Jews.”

Through their considerable role in the media, especially in television and motion pictures, the Jewish impact on every aspect of American life has been an enormous one. MacDonald reports that many Americans who are dismayed about what they regard as the socially harmful impact of television and cinema recognize the significant Jewish role in this process, but do not mention it “because of fear of being charged with anti-Semitism.”

A good example cited by MacDonald of how organized Jewry successfully wields power to further its interests is the 1948 effort to get President Truman to authorize United States support for Zionist ambitions in Palestine. He finally did so against the advice of his most trusted advisors, including Secretary of State George Marshall, who warned that US backing for the new Zionist state of Israel would have harmful long-term consequences for American interests. Truman himself commented: “I do not think I ever had so much pressure and propaganda aimed at the White House as I had in this instance.”

According to a 1985 survey, one third of San Francisco-area Jews expressed the view that anti-Semitism was so widespread that a Jew could not be elected to Congress – even though at the time three of the four area congressional representatives were well-identified Jews, as were both state senators and the mayor of San Francisco.

Another example cited by MacDonald of organized Jewry's remarkable clout is its role in pushing for liberal US immigration policies. For more than a century Jews have been at the forefront of efforts to alter the ethnic-racial composition of the United States by promoting non-European immigration. Jewish organizations such as the American Jewish Committee, he notes, have played a major role in this campaign, although often behind the scenes.

These Jewish efforts have greatly accelerated the transformation of the United States into a “multicultural” society in which the prevailing majority of European ancestry is rapidly being reduced to a minority. An important milestone in this decadeslong campaign came with the enactment of the 1965 immigration law reform, which replaced a longstanding policy of favoring immigration from Europe to one that opened the door to massive nonwhite immigration from Third World countries.

Combatting Anti-Semitism

For centuries, MacDonald shows, organized Jewry has been adept at promoting its interests in the field of public relations and propaganda aimed at both scholarly and popular audiences, and often hiring prominent non-Jews to “front” for them in defending Jewish goals.

As MacDonald notes, Jews have traditionally employed

Jews are behind a “worldwide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilization,” wrote Winston Churchill in an essay published in 1920 in the London “Illustrated Sunday Herald.” The role of Jews in the Bolshevik takeover of Russia, he went on, “is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others.”

image-management strategies, including recruiting gentiles to support Jewish causes as well as controlling the public image of Judaism via censorship of defamatory materials and the dissemination of scholarly material supporting Jewish interests.

Jewish organizations “have used their power to make the discussion of Jewish interests off limits,” MacDonald notes, putting great effort into making anti-Semitism unsavory and socially disreputable. Moreover, he observes, “individuals who had made remarks critical of Jews were forced to make public apologies and suffered professional difficulties as a result.”

In this regard, MacDonald cites the successful April 1996 campaign by Jewish journalists and organizations, including the Anti-Defamation League, to pressure St. Martin's Press, a major New York publisher, into cancelling publication of British historian David Irving's biography of Goebbels.

To conceal the self-serving nature of such efforts, Jewish groups routinely describe them as fighting “hate” or combatting “bigotry.” Jewish organizations in the United States accordingly try to gain support from non-Jews for their efforts by castigating anti-Semitism as “un-American,” just as Jewish groups in Germany during the 1870-1914 period sought support from gentiles by denouncing anti-Semitism as “un-German.”

A Dying People?

“If anti-Semitism did not exist,” writes MacDonald, “it would have to be invented.” Indeed,

some Jews have argued that because anti-Semitism sharpens Jewish identity, Judaism may not survive without it. Many Jewish leaders are alarmed that because the United States, in particular, is so welcoming of Jews, they lose all inhibitions about assimilating. Intermarriage is the ultimate act of assimilation, and conservative Jews see it as the ultimate danger. (MacDonald quotes the Jewish philosopher Emil Fackenheim to the effect that a Jew who marries a gentile gives Hitler a posthumous victory, because if all Jews marry gentiles Jews will cease to exist.) The United States, according to this argument, is ''loving Jews to death.”

There is accordingly some concern among American Jews that they will disappear as a distinct people. But MacDonald does not share this view: “Reports of the demise of Judaism – the 'ever-dying people' – are greatly exaggerated.” Over the millennia, he observes, some Jews have always been lost to Judaism as they married out, lost their tribal identities, and assimilated. Those who do not are always the most loyal, and it is this solid core that has always ensured Jewish survival and perpetuation.

Anyway, Jews historically have not had to worry much about insufficient levels of anti-Semitism. As MacDonald notes, the very customs that maintain Jewish solidarity – a clear ingroup-outgroup dual morality, promotion of group interests, and resistance to marrying outside the group – are precisely the factors that foster anti-Jewish sentiment. Consequently, he writes, Jews have been careful to strike a balance: “The best strategyfor Judaism is to maximize the ethnic, particularistic aspects of Judaism within the limits necessary to prevent these aspects from resulting in [excessive or murderous] anti-Semitism.”

Intellectuals on the Offensive

Jewish intellectuals, MacDonald writes, “have also gone on the offensive” in developing and promoting important social-intellectual movements aimed at altering the fundamental categorization process among gentiles in a manner that is perceived by the participants to advance Jewish group interests.”

He is referring here to influential liberal and leftist causes, especially in this century, in which Jews have played key roles. These movements have included the “civil rights” movement of the 1940s, 50s and 60s, the campaign to promote racial egalitarianism (in which Jewish anthropologist Franz Boas played a central role), critiques of nationalism and “racism,” the “new left” of the 1960s and 70s, Freudian psychoanalysis, and promotion of homosexuality and feminism.

Probably the most important of these movements has been Communism, which was founded by the German-Jewish scholar Karl Marx. As Macdonald notes, even Winston Churchill, in an essay published in 1920 in the London Illustrated Sunday Herald, wrote that Jews were behind a “worldwide conspiracy for the overthrow of civilization.” The role of Jews in the Bolshevik takeover of Russia, Churchill went on, “is certainly a very great one; it probably outweighs all others.” [See “The Jewish Role in the Bolshevik Revolution and Russia's Early Soviet Regime,” Jan.-Feb. 1994 Journal.]

Those who develop and promote these movements claim to be motivated by lofty humanitarian concerns, and accordingly couch their arguments in terms of democratic ideals. In reality, MacDonald maintains, this “intellectual offensive” is part of a well-established and remarkably successful Jewish pattern that seeks to advance sectarian Jewish interests by attacking traditional cultural, racial and religious values. This is because Jews thrive best in “pluralistic” societies that lack strong cultural, racial or religious characters.

Precisely how Jewish scholars and activists have carried out this offensive will be, MacDonald pledges, a “major theme” of the forthcoming, third volume in his study, entitled A Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements.

Analysis or Justification?

As MacDonald convincingly shows, anti-Semitism is not, as we are constantly told, merely an expression of irrational hatred. Throughout the ages, gentiles have had valid reason to notice and dislike the behavior of Jews. A central theme of Separation and its Discontents is that gentiles have persecuted, expelled and killed Jews, not because Jews were “Christ-killers” or because they practiced a peculiar religion, but because they entered into persistently unacceptable relations with gentile society. While MacDonald does not excuse persecution, his analysis of Jewish behavior over the centuries does make it more understandable.

This book implicitly warns us to be highly skeptical of the most widely available accounts of Jewish history and of relations between Jews and non-Jews – whether in motion pictures, magazines or books. As MacDonald notes, virtually all popularly available accounts of Jewish history are written by Jews, many of whom make no secret of their passionate, partisan attachment to their subject. The reality of Jewish history, it is important to understand, is not at all the saga of virtue and inexplicable victimization that Jewish chroniclers are wont to tell. The causes of anti-Semitism, MacDonald shows, are easily discovered and understood. Jews rarely acknowledge them because they do not want to understand their own history.

Invaluable Guide

MacDonald's brilliant, well-referenced study, with its bounty of eye-opening facts and insights, is the most important work on the perpetually troubling “Jewish question” to appear in many years. But it is much more than that. Given the extraordinary reach of Jewish influence, Separation and its Discontents is also an invaluable guide to understanding ourselves and our world.

As MacDonald's analysis implicitly makes clear, non-Jews, especially in the United States, have largely come to accept Jewish “deception and selfdeception” as normal. So many of our most widely held beliefs and assumptions about the past and the present are based not on fact but rather on what Jewish scholar Namier aptly called “Jewish martyrology.” In short, we have become accustomed to looking at history through Jewish eyes.

Implicit in MacDonald's book is a stern warning that the pattern of “deception and self-deception” he reveals has corrupted our culture, not least in grossly distorting how we look at the past, particularly 20th-century American and European history. Without an understanding of the real Jewish role in history, we remain dangerously ignorant of how the world actually works.

Uncertain Impact

Several years ago a major New York publisher issued The Bell Curve, a scholarly book by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray that powerfully debunks the central assumptions on which America's racial policies have been based. In spite of its rigorous scholarship, and even though it sold well and was widely reviewed, The Bell Curve has had no measurable impact on either popular attitudes or government policies.

Will Separation and its Discontents – another iconoclastic work of arguably comparable importance – suffer a similar fate? Or, perhaps, just perhaps, will it prove to be a seed falling on rocky but still fertile ground? If, even without fanfare, MacDonald's book is read by enough thoughtful and concerned people, it can contribute to a significantly greater awareness of ourselves and our history. It might even portend a new era in America and the world.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 17, no. 3 (May/June 1998), pp. 28-37

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a