German Poison Gas (1914 – 1944) (2008)

When the public thinks about the topic of German or Nazi poison gas development and usage throughout the years leading up to and including the Second World War, images of vast extermination programs and the gas chambers of Auschwitz and other concentration camps immediately leap to mind. The Holocaust story however suggests that the Nazis utilized methods, equipment and gas that were put to use in a way and for a purpose other than for which they were designed. It is suggested that, in a rather primitive way, the various Concentration camp personnel developed different methods to put into effect what is argued was a coordinated extermination program for Jews.

The traditional Holocaust story suggests the importance of adapting equipment and methods to put into effect a centrally organized program for mass-murder. It will be argued that had the Nazi leadership designed a program for the mass extermination of Jews that the weapons of such mass destruction were already developed and could have easily been used. Nazi chemical warfare development was the most sophisticated in the world. The poison gas developed during the years leading up to the Second World War make the traditional Holocaust story absurd. There is no reason whatsoever that the Nazis would have needed to adapt Soviet tanks or divert the use of Zyklon B from delousing programs designed to keep inmates alive to programs of extermination.[1] The weapons required for an extermination program not only existed but were manufactured in quantities that would have supported such a program had one been ordered.

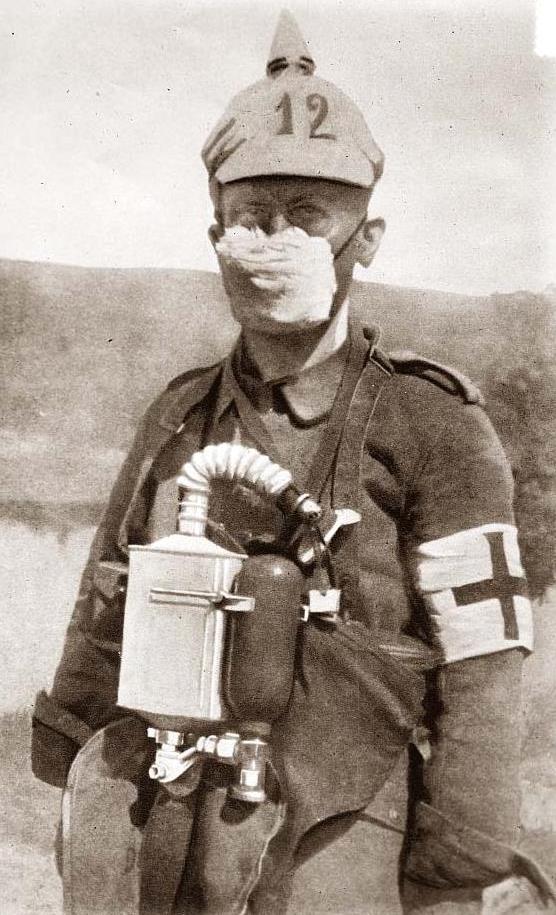

The Use of Poison Gas During World War I

German World War One soldier with gas protection equipment

To understand German poison gas capabilities during World War Two, it is important to consider briefly the use of poison gases during World War One. During the First World War both sides used large quantities of poison gas. Over 1.3 million tons of chemical were used throughout the war in agents ranging from simple tear gas to mustard gas. [2] At the time that the war began, Germany had the leading chemical industry of any of the combatants; in fact, they were the leaders in the entire world. The major chemical factories were situated in the Ruhr and were known as the Interessen Gemeinschaft Farben or I.G. Farben.[3]

The introduction of chemical warfare was actively lobbied by I.G. Farben and by its head, Carl Duisberg. Duisberg not only urged that the German high command use poison gas at a special conference in 1914, he personally studied the toxicity of the various war gases.[4] Duisberg also supported Fritz Haber, Germany's leading scientist at the time and head of its premier scientific laboratory, the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry in Berlin. In his studies of the effects of poison gas, Haber noted that exposure to a low concentration of a poisonous gas for a long time often had the same effect (death) as exposure to a high concentration for a short time. He formulated a mathematical relationship between the gas concentration and necessary exposure time. This relationship became known as Haber’s rule.[5]

During World War I, the Germans and the Allies both used several types of poison gas rather effectively. These ranged from chlorine gas early in the war to phosgene gas which was introduced by I.G. Farben. Phosgene was about 18 times as powerful as chlorine gas. Concentrations as low as 1/50,000 were deadly.[6] Throughout this period, the Germans would develop and initiate the use of several new gases only to have them copied by the Allies. In July 1917, I.G. Farben created a new gas initially called “Yellow Cross” by German artillerymen. Yellow Cross was more lethal than anything that had come before. This gas, dichlorethyl sulphide came to be known as “mustard gas.”

Troops that were attacked by mustard gas initially reported only mild irritation to the eyes. It appeared to do little or nothing and many troops did not bother to put on their gas masks when they encountered the gas. Within a day, however, they would be in terrible pain. Troops developed moist red patches on their skin that grew into large yellow blisters up to a foot long. Those hit with mustard gas would die a slow agonizing death. In a ten day period the Germans used over a million shells containing 2,500 tons of mustard gas against Allied positions.[7] As a side note, the British too would use mustard gas in the final days of the war. In one attack on October 14, 1918 Adolf Hitler would be temporarily blinded by a British attack against the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment.[8]

The Interwar Years

German solider in World War One with dogs equipped with gas masks.

In the years following the First World War, the major combatants announced their opposition to the use of chemical warfare. In Geneva in 1925 representatives of the major powers signed a legal constraint against the use of chemical warfare. Still, during the “interwar” years, various European powers did in fact use poison gas. Among them were the British (against the Soviets in 1919), the Italians (against the Ethiopians in 1935), and the Japanese (against the Chinese in 1937).[9]

Throughout these years I.G. Farben continued to expand its scientific base. From the laboratories of Bayer, one part of the I.G. Farben cartel, a scientist, Gerhardt Schrader, made a major breakthrough. On December 23, 1936 he prepared a new chemical as part of a part of a study of potential pesticides. During the test, Schrader used his new compound on lice in a concentration of 1 / 200,000. All of the lice died within a few seconds.[10]

By January of 1937, Schrader discovered that his new agent had unpleasant side effects on humans. The compound that Schrader developed was Tabun, the worlds’ first nerve gas. Tabun represented an exponential leap in toxicity level of poison gases. Even in very small amounts, the inhalation or absorption through the skin of Tabun affected the central nervous system and resulted in almost immediate convulsions and death.[11] Tabun was so lethal that it quickly became clear that it could not be used as an insecticide. Schrader, however contacted the war ministry and tests were carried out for the Wehrmacht.

By 1938, Schrader was moved to a new location to develop new compounds for the Wehrmacht. He discovered yet another compound, isopropyl methylphosphonofluoridate which he named Sarin. In the initial tests of Sarin gas on animals, it was discovered that Sarin was ten times as lethal as Tabun.[12] At the close of the war, German chemists were actively engaged in the development of Soman gas. Soman, another organic chemical related to Tabun, was estimated to be 200 times more deadly than Tabun.

Poison Gas and the Holocaust Story

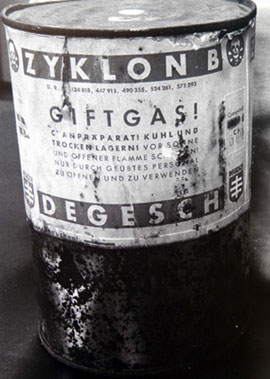

Despite the toxicity and huge stores of these lethal nerve gases, the Holocaust story developed around the use of two gases, carbon monoxide and Zyklon B. Zyklon B was developed during the 1920s when scientists working at Fritz Haber’s institute developed this cyanide gas formulation to be used as an insecticide, especially as a fumigant for grain stores.[13] I.G. Farben, interestingly would sell the production rights of Zyklon B right before the war to two private firms, Tesch and Stabenow, of Hamburg and DEGESCH, of Dessau.

As the story goes, four out of six of the principal “killing centers” used carbon monoxide gas, which allegedly was generated through the use of rather disparate equipment. In Chelmno, according to Arno Mayer prisoners were “herded into the vans in which they were asphyxiated with carbon monoxide fumes.” He goes on to note, “There was nothing particularly modern or industrial about either the installations or the operations at Chelmno-Rzuchow.”[14]

Canister of Zyklon B produced by DEGESCH

The second alleged killing center was Belzec. There we are told that after using bottled carbon monoxide, the operatives switched to using exhaust fumes from trucks.[15] In Sobibor, we are told that the gas was generated through an engine. If we are to believe Kurt Gerstein, Zyklon B was delivered there for sinister purposes as well. [16] At times we have also read of a submarine engine at Sobibor used to generate CO to kill Jewish inmates.[17] In Treblinka we read of carbon monoxide pumped into a chamber from the diesel exhaust of a captured Soviet tank. Even the orthodox Holocaust story contains an episode in which Auschwitz Commandant Höss visits Treblinka and concludes that the killing method there is inefficient.[18]

The final two “extermination centers” Majdanek and Auschwitz are said to have used Zyklon B as the agent of extermination. The killing process described at Auschwitz requires that someone climbs a ladder above the “gas chamber” opens the can of Zyklon B with a special can opener and shakes out the solidified pellets of hydrogen cyanide into a special shaft in the supporting column of the chamber where the pellets would over time turn into a gaseous state.[19] The absurdity of the Zyklon B story is that even orthodox Holocaust historians like Jean-Claude Pressac and Robert Jan van Pelt have admitted that typhus epidemics experienced at the camps required that everything be deloused and that “tons of Zyklon B were needed to save [Auschwitz].” [20] So, the story goes, that on one hand, the Nazis were using Zyklon B to delouse the camps and thereby prevent the spread of typhus, while on the other hand they were using the same agent to kill the very inmates whose lives they were attempting to save.

The Holocaust gassing story suggests a lack of coordination by the Nazi government. There is a simultaneous adoption of varied methods, which would have yielded varied results to carry out what is typically described as a centralized industrial “genocide.” In fact, the official Holocaust story itself suggests that the program was anything but centrally organized and the methods were evolved in a rather chaotic manner in the field.

Based on the development of sophisticated poison gases including Tabun and Sarin, and their manufacture in huge quantities, the official Holocaust story appears absurd.[21] Holocaust historians have yet to answer the question why the Nazis would not have used Tabun or Sarin had they wanted to carry out an extermination of the Jews. Furthermore, even in the final days of the war, when the Nazi leadership sought out new-sophisticated weaponry, they did not use their stockpiles of poison gas on either front. This stands in stark contrast to the popular image of Nazi methods and thinking.

There is little doubt that the Soviets discovered significant quantities of Zyklon B when they arrived at Auschwitz and Majdanek that were there to combat typhus rather than to kill the inmate population. Similarly the tales of submarine engines and captured Soviet tanks pouring out diesel exhaust for mass murder appear to be nothing more than the result of wartime propaganda. Had the Nazi leadership wanted to exterminate the Jews of Europe, they had far more sophisticated and lethal means to carry out such a plan. The official Holocaust gassing story requires a suspension of reason and a belief in the absurd.

Notes

- [1]

- Jean-Claude Pressac and Robert-Jan van Pelt, “The Machinery of Mass Murder at Auschwitz.” Chapter 8 of Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Yisrael Gutman and Michael Berenbaum, editors. Indiana University Press. Bloomington and Indianapolis, p. 215. Pressac and van Pelt recount the incredible story of the Nazi SS utilizing 95% of Zyklon B shipments to Auschwitz for delousing purposes in order to keep inmates alive, while siphoning off 5% to operate the alleged gas chambers to execute the same inmate population.

- [2]

- David Tschanz, “A Whiff of Death: Chemical Warfare in the World Wars.” Command Issue 33, Mar-Apr 1995. XTR Corporation, San Luis Obispo, CA 93403, p. 48.

- [3]

- The Empire of I.G. Farben. http://reformed-theology.org/html/books/wall_street/chapter_02.htm

- [4]

- Tschanz, p. 49.

- [5]

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fritz_Haber

- [6]

- Tschanz, p. 52.

- [7]

- Tschanz, p. 53.

- [8]

- William Moore, Gas Attack! Chemical Warfare 1915-18 and afterwards. Leo Cooper, New York, 1987, p. 223.

- [9]

- Tschanz, p. 54-55.

- [10]

- Tschanz, p. 55.

- [11]

- Ibid.

- [12]

- Ibid.

- [13]

- M. Szöllösi-Janze (2001). “Pesticides and war: the case of Fritz Haber”. European Review 9: 97–108

- [14]

- Arno J. Mayer, Why Did the Heavens Not Darken? The “Final Solution” in History. Pantheon Books, New York, 1988, p.391.

- [15]

- Mayer, p. 402.

- [16]

- For a thorough analysis see Henri Roques, The 'Confessions' of Kurt Gerstein, Institute for Historical Review, Costa Mesa, CA, 1989.

- [17]

- Friedrich Paul Berg, The Diesel Gas Chambers: Myth Within a Myth. Journal of Historical Review, Vol. 5, No. 1, Spring 1984. Institute for Historical Review, p.23.

- [18]

- Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, Quadrangle Books, Chicago, 1967, p. 565.

- [19]

- Pressac and van Pelt, p. 235.

- [20]

- Ibid, p. 215.

- [21]

- In a reworked version of his classic article on the diesel gas chambers, Friedrich Berg made exactly such a claim. In fact he renamed his article, “The Diesel Gas Chambers: Ideal for Torture – Absurd for Murder.” See Ernst Gauss, Dissecting the Holocaust, Theses & Dissertations Press, 2000.

This article was originally published in abbreviated format in Smith's Report No. 152, July 2008.

Bibliographic information about this document: originally published in abbreviated format in Smith's Report No. 152, July 2008

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a