The Maly Trostenets “Extermination Camp,” Part 1

A Preliminary Historiographical Survey, Part 1

1. Introduction

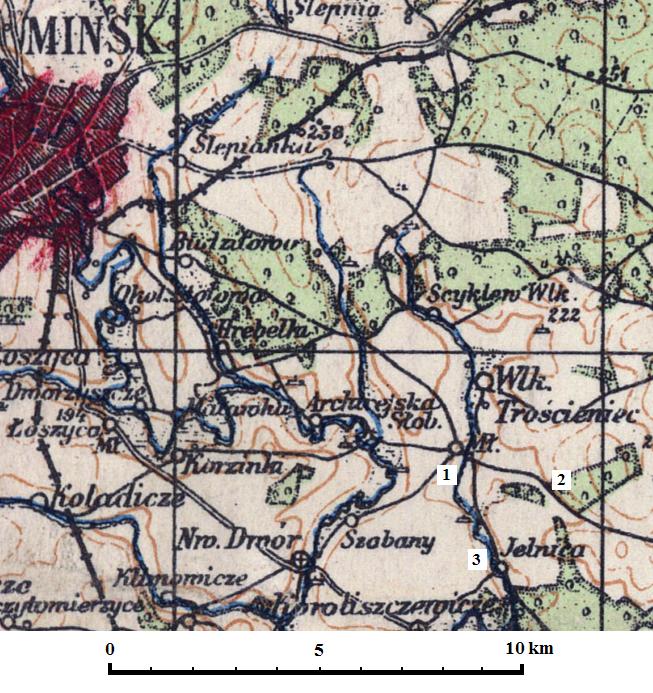

While it is well known to all with an interest in Holocaust historiography that the Germans operated six alleged “extermination camps” in Poland – Auschwitz-Birkenau, Majdanek, Chełmno (Kulmhof), Treblinka, Bełżec and Sobibór – and while some may be familiar with the claim that the camp Stutthof near Danzig (Gdansk) functioned as an “auxiliary extermination camp”[1], it is practically unknown to all but those with special interest in the Holocaust in Belarus that another alleged “extermination camp” was operated by the Commander of the Security Police and Security Service Minsk (Kommandeurs der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD (KdS) Minsk)[2] between 1941 and June 1944 at the former Soviet kolkhoz (collective farm) “Karl Marx” in the village of Maly Trostenets, some 12 km southeast of Minsk.

The principal victims of Maly Trostenets are supposed to have been Jews from the Minsk Ghetto, as well as Jews deported directly to Belarus from Austria, Germany and the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia. The latter were initially sent from the Minsk freight railway station in open trucks to the former kolkhoz, which had been renamed “Gut Trostinez” (Trostinez Estate) by the Germans and housed some 400 to 1200 prisoners. The mass killings were allegedly carried out by shooting, or in “gas vans”, at the two nearby forest sites of Blagovshchina and Shashkovka. The latter was used from October 1943 onwards. In 1944 a further group of victims were shot or burned alive inside barns at the camp itself. Many of the alleged victims of 1942 are supposed to have been Jews from Austria, Germany and the Protectorate deported to Minsk. At their arrival in the Belorusian capital these Jews were loaded onto open lorries and brought to Trostenets, where they were (allegedly) either murdered in gas vans or shot. In August 1942 a new railway track and an improvised railway station made it possible to send the Jewish train convoys directly to Trostenets. According to mainstream historiography no transports of Jews from the west took place during 1943 (or 1944).

The historiographical designation of the Maly Trostenets camp requires some elucidation. While many holocaust historians simply call Trostenets an “extermination site” or “execution site”, numerous books also refer to it as an “extermination camp” or “death camp”. This appears to be a growing trend. Already in a newspaper article from July 1944 Trostenets was referred to as “a death camp for Czech, German and Austrian Jews”. In 1999 German holocaust historian Christian Gerlach again labeled it a “death camp”.[3] The only monograph on Trostenets to appear to date in any Western European language, written by the journalist Paul Kohl and published in 2003, bears the title Das Vernichtungslager Trostenez (The Trostenez Extermination Camp). The online encyclopedia Wikipedia speaks of the “Maly Trostenets extermination camp”.[4] The exterminationist website ARC writes that “Insufficient research has been conducted in the West into Maly Trostinec, yet those killed there may have been comparable in number to the victims of Majdanek or Sobibor, and may possibly have been greater.”[5] In 2005 a Russian article appeared bearing the title “Trostenets – The Byelorussian ‘Auschwitz’”.[6]

From an exterminationist viewpoint, the label of “death camp” does indeed seem logical, as the camp is supposed to have been rather similar to Chełmno in its alleged structure and functioning, with the exception that most of the (alleged) victims were shot rather than murdered in “gas vans”. In both camps the victims immediately upon arrival were “deceived” into believing that they would be transferred somewhere else, and were then promptly murdered and buried in a nearby forest. In Chełmno, the few hundred inmates of the camp proper were selected from the arriving Jewish transports and worked with sorting the confiscated belongings of the [allegedly] murdered Jews, as well as with the burial and cremation of the victims. In Trostenets, some two-thirds of the camp population were selected from the arriving Jewish convoys; the rest were Soviet POWs. The work in the camp consisted of sorting the belongings of the [allegedly] murdered Jews, as well as agricultural work and a number of other labor tasks; the burial and subsequent cremation of the alleged victims was performed not by Jews, but by Soviet POWs. As may be seen, there are more similarities than differences between the respective historiographical pictures.

That some holocaust historians hesitate to call Maly Trostenets a “death camp” may be in part due to a downward revision of its victim figure in later years, part due to the fact that, as the above-mentioned ARC website article puts it, “there was no overall command structure, as existed in the Aktion Reinhard camps, and thus a less organised pattern of crime.” Yet regardless of the historiographical perspective, Trostenets, with its provisional railway station, assembly square and barracks, stands out as something more complex than alleged mass killing sites such as Babi Yar, which supposedly consisted of little more than mass graves and corpse pyres. Moreover, although the alleged infrastructure of mass murder was provisional, it was reportedly in use for more than two years, a longer period than any of the Reinhardt camps (or Chełmno) was in operation.

As will be seen below, the estimates for the total number of Trostenets victims vary greatly, from 40,000 to 546,000. Between the end of October and mid-December 1943, all buried victims were allegedly exhumed and cremated on open-air pyres by the enigmatic “Sonderkommando 1005”. Chiefly responsible for the camp was the head of KdS Minsk, SS-Obersturmbannführer Eduard Strauch (1906-1955; also leader of the Einsatzkommando 2 of Einsatzgruppe A).[7] The overall command structure of the camp remains unclear. One witness, however, names an “SS-Obersturmführer Maywald” as camp commandant.[8] According to Paul Kohl, the camp commandants were, in chronological order: Gerhard Maywald, Heinrich Eiche, Wilhelm Madeker, Wilhelm Kallmeyer and Josef Faber.[9] Confusingly, a certain Rieder is named as camp commandant by other sources.[10] The logistical handling of the arriving transports from the west was taken care of by SS-Obersturmführer Georg Heuser, who was also a member of Einsatzgruppe A.[11]

In the following article I will present a brief chronological survey of the literature discussing the Trostenets camp[12], together with some comments on anomalies, incongruities and contradictions to be found within the orthodox version of events. It is not to be viewed as a detailed critique of the various claims regarding this camp, but rather as a an overview and a stepping-stone for further research.

Throughout the literature the name of the camp is rendered in various ways due to the different methods of transliterating the cyrillic script (Trostinetz, Trostinec, Klein Trostinetz[13], Trostyanets, Trastyanets, Trascianiec, Malyi-Trostiniets). I have here chosen to use the form “Maly Trostenets” as this is in accord with the modern standard of transliteration used in the English-speaking world (as well as the spelling championed by the English edition of Wikipedia).

2. A Chronological Survey of the Literature on the Maly Trostenets camp

2.1. Official Soviet Statements and Court Material (1942-44)

In a “Report on crimes committed by the German-Fascist invaders in the city of Minsk”, originally published in Soviet War News, no. 967 of 22 September 1944, we find the following two paragraphs mainly devoted to the Trostenets camp:[16]

“GERMAN SECRET POLICE CAMP IN MALY TROSTINETS

Near the village of Maly Trostinets, about six miles from Minsk, the German-Fascist invaders set up a concentration camp[15] conducted by the German Secret Police, in which they kept civilians doomed to death. At the Blagovshchina site, about a mile from the camp, they used to shoot camp inmates and bury their bodies in trenches. In the autumn of 1943, with a view to covering up the traces of their crimes, the Germans started to unearth the pit graves and to exhume and burn the bodies. A resident of the village of Trostinets, Golovach, saw how ‘the German hangmen killed men, women, old men and children in Blagovshchina Forest; they put the bodies of murdered people into previously prepared trenches. […] They packed them down with bulldozers, then placed another layer of bodies on top and packed them down again. In the autumn of 1943 the Germans opened the trenches in Blagovshchina and started burning the exhumed bodies. They mobilized all the carts from neighboring villages to bring up firewood for the purpose.’

In the autumn of 1943 the invaders built a special incinerator on the Shashkovka site, about a quarter of a mile from Maly Trostinets Concentration Camp. Kovalenko and Kareta, who worked at the concentration camp, stated that the bodies of the people shot or murdered in ‘murder vans’ were burned in this incinerator. Three to five trucks packed with people arrived there every day.

‘I saw every day’ (stated Bashko, a resident of the village of Maly Trostinets) ‘how the German bandits, headed by the commandant of the ghetto camp, the hangman Ridder, killed civilians in Shashkovka Forest and then burned their bodies in the incinerator. I grazed cattle not far from this incinerator and often heard the cries and wails of people pleading for mercy. I heard tommy-gun bursts, after which the wailings of the unfortunate people ceased.’

The Investigation Commission examined an incinerator. The examination disclosed inside rails on which were placed metal sheets with holes in them, as well as a huge quantity of small charred human bones. A special drive for trucks had been laid to the incinerator. A barrel and scoop with remnants of tar were found at the mouth of the furnace. Various personal belongings of the executed people were scattered on the spot, such as footwear, clothing, women’s blouses, headgear, children’s socks, buttons, combs and penknives. Judging by the tremendous quantity of spent cartridge cases and fragments of exploded hand grenades, the Germans had shot their victims at the mouth of the furnace and inside the furnace itself. Tar was poured on the bodies and firewood placed between them. Incendiary bombs were placed inside the furnace in order to raise the temperature.

In view of the Red Army’s rapid advance to the west, at the end of June 1944, the Hitlerite hangmen devised a new method for the mass extermination of Soviet civilians. On June 29-30 they started taking inmates of the concentration camps and the bodies of those who had been shot to the village of Maly Trostinets. The corpses were stacked up in sheds, where the Germans also shot Soviet people, and the sheds were then set on fire. Savinskaya, who escaped death, stated to the Investigation Commission:

‘I resided on German occupied territory, in Minsk. On February 29, 1944, the German-Fascist invaders arrested me and my husband Yakov Savinsky for connections with partisans, and put us in the Minsk jail. In mid-May, after long and terrible tortures in which we did not confess our connections with the partisans, I and my husband were transferred to the S.S. concentration camp in Shirokaya Street, where we were kept until June 30, 1944. On that day, with fifty other women, I was put into a truck and taken to an unknown destination. The truck drove about six miles from Minsk to the village of Maly Trostinets and stopped at a shed.

‘Then we realized we had been brought there to be shot… On the command of the German hangmen the imprisoned women came out in fours from the lorry. My turn soon came. With Anna Golubovich, Yulia Semashko and another woman whose name I do not know I climbed on top of the stacked bodies. Shots rang out. I was slightly wounded in the head and fell. I lay among the dead until late at night, Then I got out of the shed and saw two wounded men: the three of us decided to escape. The German guard noticed and opened fire. Both men were killed. I succeeded in hiding in the swamp. I stayed there for fifteen days without knowing that Minsk had already been captured by the Red Army.’

On examining the remains of the shed at Maly Trostinets, burned down by the Germans, the Investigation Commission discovered a tremendous quantity of ashes and bones, also some partly preserved bodies. Alongside on a pile of logs there were 127 incompletely charred bodies of men, women and children. Some personal articles lay near the site of the fire.

The medico-legal experts have discovered bullet wounds on the bodies in the region of the head and neck. On piles of logs and in the shed the Germans shot and burned 6,500 people.

HITLERITES TRIED TO COVER TRACES OF THEIR CRIMES

Three miles from the city [of Minsk], by the Minsk-Molodechno railway near the village of Glinishche, the Investigation Commission discovered 197 graves of Soviet people who had been shot by the Germans. […] Here were buried Soviet prisoners of war who had been kept in ‘Stalag No. 352′ and were murdered by the camp guard headed by the German commandant, Captain Lipp. […] About 80,000 Soviet war prisoners were buried in the cemetery near the village of Glinishche.

Thirty-four grave pits camouflaged by fir-tree branches have been discovered in Blagovshchina Forest; some of the graves are no less than 50 yards long. Charred bodies covered with a layer of ashes 18 inches to one yard thick were found at a depth of three yards in five graves when they were partly opened. Near the pits the Commission found a great quantity of small human bones, hair, dentures and many personal articles. Investigation has revealed that the fascists murdered about 150,000 people here.

Eight grave pits 21 yards long, four yards wide and five yards deep have been discovered at about 450 yards from the former Petrashkevichi hamlet. […] Investigation has established that the Germans burned some 25,000 bodies of civilian Minsk residents whom they had shot.

Ten grave pits were discovered about six miles along the Minsk-Moscow motor road at the Uruchye site. Eight of these graves are 21 by 5 yards, one is 35 by 6 yards and one is 20 by 6 yards. All of them are three to five yards deep. The Commission has discovered three rows of bodies lying lengthwise, in seven layers each. All the corpses were lying face down, and many were in Red Army tank troops uniform. […] Several bodies of women in civilian clothes were also found in the graves. […] The total number of those shot and buried on the territory of the Uruchye site, according to the testimonies of prisoners of war and the data of experts, exceeds 30,000.

Northeast of the concentration camp[?], on the territory of the Drozdy Settlement, there was discovered a ditch 400 yards long, two and a half yards wide and two and a half yards deep. In the course of excavations conducted in several places in the ditch to a depth of 18 inches there were found remnants of bodies (skulls, bones) and decayed clothes. Investigation revealed that about 10,000 Soviet citizens shot by the Germans had been buried in this ditch.

Mass graves of Soviet people tortured to death by the Germans have also been discovered at the Minsk Jewish cemetery, in Tuchinka, in Kalvariskoye Cemetery in the Park of Culture and Rest and in other places.

The Medico-Legal Commission of Experts consisting of Academician Burdenko, of the Extraordinary State Commission, Doctor of Medicine Professor Smolyaninov and Doctor of Medicine Professor of Forensic Medicine Chervakov, has established that the German scoundrels exterminated peaceful residents and Soviet prisoners of war by hunger and work beyond human strength, poisoned them with carbon monoxide and shot them. Investigation has revealed that in Minsk and its outskirts the Hitlerites exterminated about 300,000 Soviet citizens, excluding those burned in the incinerator.”

According to a Soviet report from 25 July 1944 on “Violent crimes committed in the concentration camp near the village of Trostenets”, which I do not have at my disposal but which is referenced by historian Christian Gerlach, no fewer than 546,000 people were murdered in Maly Trostenets.[17] This figure apparently came to be seen as incredible and was thus discarded, even though it would surface once or twice in the later literature.

What is particularly striking about the September 1944 report is that virtually no information is provided regarding the alleged victims. Who were they, and where did they come from? We merely learn that they were part of the “300,000 Soviet citizens” exterminated by the Germans “in Minsk and its outskirts”, a statement which seems to exclude transports of Jewish victims from the west. Nonetheless, in an official statement issued on 19 December 1942 by the Information Bureau of the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, we read that “Brutal massacres of Jews brought from Central and Western Europe are also reported from Minsk, Byelostok, Brest, Baranovici and other towns of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.”[18] Of course, according to postwar historiography there were never any transports of Jews to Belarus from the German-occupied countries in Western Europe (i.e. France, Belgium and Holland).

From the German journalist Paul Kohl we learn that the alleged mass murders at Trostenets were included in a trial which took place in Minsk in January 1946, and that protocols from this trial were published in Minsk in 1947.[19] Unfortunately I have not been able to procure this volume, the title of which Kohl neglects to mention.

It is clear that an unknown number of former Trostenets inmates were questioned in summer 1944 in connection with the investigations of the Extraordinary State Commission. Two extracts from the protocols of these interrogations were scheduled for publication in Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman’s Black Book under the heading “From Materials Compiled by the Special State Commission on the Verification and Investigation of Atrocities Committed by the German-Fascist Invaders”, but were excised from the published volume. Much later the extracts were included in a “complete” edition of the Black Book, from which I have quoted the most relevant portions. The first extract is headed “Protocols for Inquest Witness Mira Markovna Zaretskaya, 9 August 1944”:[21]

“Burdenko: What did you see in the [Maly Trostenets] concentration camp? How were the prisoners of war and civilians confined there?

Zaretskaya: Prisoners of war and other prisoners lived in one barracks. It was very crowded. It was not a barracks really, but more like a shed. Prisoners and soldier stayed together. The Jews lived over the workshops.

Burdenko: Were the women housed separately?

Zaretskaya: There were no women among the prisoners of war or the other prisoners. The Jewish women lived separately; only families stayed together.

Burdenko: What do you know about the mass shootings and when did they begin?

Zaretskaya: The shootings began in the camps in October 1943.[20] Every day I saw covered trucks taking people from Minsk to be shot and burned in pits. From 23 June [1944] on a very large number of trucks came, more than you can count.

Burdenko: Did you see people burned in the crematoria?

Zaretskaya: I myself did not see people burned, but I saw the smoke and the flames, and I heard the shooting.

Burdenko: Did they tell you in the camp how many prisoners had been burned?

Zaretskaya: Very many were burned. I would estimate half a million. From the villages in the area they brought in the families of people who had joined the partisans.”

One immediately notes here that Zaretskaya’s statements concerning the alleged extermination are either based on hearsay or inconclusive auditory and visual impressions. While it is mentioned by her that Jews were detained in the camp, there is no mention of Jews being murdered en masse; the only massacre victims identified are the families of partisans (of unstated ethnicity).

The second extract is from the “Protocols for Inquest Witness Lev Shaevich Lansky, 9 August 1944”:[22]

“Lansky: […] I was in a concentration camp from 17 January 1942, in the Trostyanets camp.

Burdenko: Could you move freely about the camp?

Lansky: I got around.

Burdenko: When did the Germans start burning the bodies?

Lansky: I couldn’t tell you the exact date. It was about eight months ago. I was there temporarily, from 5 January 1943.

Burdenko: Did they actually burn bodies right before your eyes?

Lansky: I saw it myself. I was working there as an electrician, and whenever I climbed up a pole to work the wires, I could see everything.

Burdenko: Did you see the Germans burning people alive?

Lansky: Yes, they burned people alive.

Burdenko: Where did they burn people alive?

Lansky: In the camp. They would set a storehouse on fire and force people into it. Meanwhile they were gassing people in the mobile vans all the time.

Burdenko: When was the last time they burned people?

Lansky: The 28th of June [1944].

Burdenko: Did you see them burn the last of the women and children alive?

Lansky: Yes. I saw it.

Burdenko: Did you hear the screams, wails, and crying of the children who were led into the flames?

Lansky: Yes. I heard and saw it all myself.

Burdenko: Did you know there was an oven there?

Lansky: There was a pit nine meters by nine meters. We dug it ourselves. That was about eight months ago.

Burdenko: I was not involved in its construction myself, but I could tell from a distance that they used iron rails. They would start it with a small incendiary bomb and then pile on large pieces of wood.

[…]

Lansky: […] We all got soap and clothing from German Jews who had been slaughtered. There were ninety-nine transports of a thousand people each that came from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia.

Burdenko: Where are they?

Lansky: All shot.

Burdenko: How many were burned in Trostyanets, besides the Jews from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia?

Lansky: Around 200,000 people. I don’t know exactly how many were shot before I got there; 299,000 people were shot while we were there.”

Lansky’s statement on the cremations stand in contradiction to the official version, which has it that cremations at Blagovshchina began in October 1943, while the “oven” at the Shashkovka site, which is located some half a kilometer south of the kolkhoz, not far from Shashkovka Lake, was constructed around the same time, “in the autumn of 1943”. Lansky’s dating would put the beginning of cremations sometime in January or February 1944. One should recall here that the work of cremating the bodies buried at the Blagovshchina site reportedly had been finished already in mid-December 1943.

The witness connects the “oven” with killings that allegedly took place in 1944, when the Blagovshchina site according to all sources was no longer in use. Yet the oven described by him – “a pit nine by nine meters” using “iron rails” with an “incendiary bomb” and “large pieces of wood” piled on top – fits the open air pyres allegedly used by the “Sonderkommando 1005” at Blagovshchina to a tee[23], but not the oven construction with perforated metal sheets reportedly discovered by the Extraordinary State Commission at the Shashkovka site! Note well that it is the ESC investigator Burdenko, not Lansky himself, who brings the subject of the oven into the interrogation.

The number of murdered Jews from Central Europe alleged by Lansky is, needless to say, much higher than asserted by mainstream historians, who generally gives estimates of between 15,000 and 20,000.

It is noteworthy that despite Lansky’s testimony, the September 1944 report did not mention any non-Soviet Trostenets victims. Nonetheless it is clear that the claim of the murder of this group of Jews existed early on (at the latest in mid-July 1944, see below, §2.2.), even if it was not officially sanctioned right away.

Despite the enormous victim figure ascribed by Soviet propaganda to Trostenets it would take until 1963 before a memorial was put up – although not at the former camp site, but near the village of Bolshoi Trostenets![24]

2.2. H.G. Adler (1955/1960)

In 1955 the Czech-Jewish novelist and amateur historian Hans Günther Adler published a study in which he chronicled in great detail the Theresienstadt ghetto where he himself had been detained 1942-1944. Unfortunately I have not been able to procure the original edition of this work, but only a second, slightly revised edition dating from 1960. In this edition Trostenets is described thus:[25]

“Trostinetz, eight miles from Minsk, was a death camp for Czech, German and Austrian Jews. In 1942 39,000 victims were brought here.”

An article which appeared in the German-Jewish expatriate weekly Aufbau on 21 July 1944 is given as source. This tells the story of Ignatz Burstein, a Jew who is stated to have been deported by the Germans from Łódz to the Belorusian city of Baranovichi in 1941 – something which contradicts mainstream historiography on the Jewish deportations from that Polish city – and who after surviving two massacres was transferred “in the autumn of 1942” from the Baranovici ghetto together with two-hundred other skilled Jewish workers, first to an unnamed penal camp, then to Maly Trostenets, “located eight miles from Minsk”. The article continues:[26]

“That was a death camp for Czech, German and Austrian Jews. All in all 39,000 Jews were transported to Trostinetz during 1942. Of each group [read: convoy] of 1000 people only 5 to 30, and then only trained workers, were left alive. In total 500 people were saved from death in Trostinetz. They worked with sorting the clothes of the murdered Jews, which were to be dispatched to Germany. Others, among them Burstein, were brought every morning to the automobile repair shops in the city [of Minsk] and had to return to the camp in the evenings.”

Elsewhere in his book Adler concludes that “in the period from 14 July to 29 September 1942” there were five “certain”, five “likely” and two “possible” transports of Jews from Theresienstadt to Belarus and “mainly to Trostinetz near Minsk”.[27] According to the present view of the Institut Theresienstädter Initiative, there were only 6 such transports during the period in question (5 to Trostenets, 1 to Baranovichi); of the other 6 outgoing Theresienstadt transports from the same period 5 were sent to Treblinka and 1 to Riga.[28]

2.3. The 1963 Koblenz Trial against Heuser et al.

In 1963 eleven former members of the KdS Minsk – Georg Heuser, Karl Dalheimer, Johannes Feder, Arthur Harder, Wilhelm Kaul, Friedrich Merbach, Jakob Oswald, Rudolf Schegel, Franz Stark, Ernst von Toll and Artur Wilke – were tried by the Landesgericht Koblenz. A considerable part of the charges related to the alleged mass murders at Maly Trostenets.

Based on the preserved railway documents known at that time, the court determined that sixteen transports had reached Trostenets (see table below). The first eight transports arrived in Minsk, where the deportees were loaded on trucks and brought to Trostenets; the latter eight transports arrived directly by train at Trostenets, via the Kolodishchi station, which is the second stop on the Minsk-Smolewiece line.[29] The “minimum number of killed” for each convoy was estimated considering likely en route deaths and the selections for work at Trostenets.

While the court took pains to determine the number of deportation trains, their departure and arrival dates, as well as the number of deportees, there is no hint in the verdict that any kind of verification was carried out of the claim that the vast majority of the deportees had indeed been murdered following their arrival at Trostenets. Rather it appears that this was taken judicial notice of based on a sworn statement that the former Kds Minsk head Eduard Strauch had made in January 1948.[30] The defendants naturally resorted to the well-known strategy of denying personal involvement in certain alleged cases of mass murder and claiming that they acted on orders under the threat of death. Heuser was so bold as to assert that, because of technical reasons, two of the convoys in the summer had not been murdered on arrival but sent on to the Minsk Ghetto and only exterminated later, something which was dismissed by the court on the ground that a number of Jewish witnesses from the ghetto did not recall any such arrivals of Jews.[31]

| Train no. | Departure | Deportees | Arrival date | Destination | Min. no. killed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Da 201 | Vienna | 1,000 | 11 May 42 | Minsk | 900 |

| Da 203 | Vienna | 1,000 | 26 May 42 | Minsk | 900 |

| Da 204 | Vienna | 998 | 1 Jun 42 | Minsk | 900 |

| Da 205 | Vienna | 999 | 5-9 Jun 42 | Minsk | 900 |

| Da 206 | Vienna | 1,000 | 15 Jun 42 | Minsk | 900 |

| Da 40 | Königsberg | 465 | 26 Jun 42 | Minsk | 400 |

| Da 220 | Theresienstadt | 1,000 | 18 Jul 42 | Minsk | 900 |

| Da 219 | Cologne | 1,000 | 24 Jul 42 | Minsk | 900 |

| Da 222 | Theresienstadt | 993 | 10 Aug 42 | Trostenets | 900 |

| Da 223 | Vienna | 1,000 | 21 Aug 42 | Trostenets | 900 |

| Da 224 | Theresienstadt | 1,000 | 28 Aug 42 | Trostenets | 900 |

| Da 225 | Vienna | 1,000 | 4 Sep 42 | Trostenets | 900 |

| Da 226 | Theresienstadt | 1,000 | 12 Sep 42 | Trostenets | 900 |

| Da 227 | Vienna | 1,000 | 18 Sep 42 | Trostenets | 900 |

| Da 228 | Theresienstadt | 1,000 | 25 Sep 42 | Trostenets | 900 |

| Da 230 | Vienna | 547 | 9 Oct 42 | Trostenets | 500 |

| Total: | 15,002 | 13,500 |

The alleged extermination of the arriving convoys is described in the verdict as follows:[34]

“In order to be able carry out the extermination of so many people smoothly and within a short period of time, Kommandeur Strauch made extensive organizational preparations. As the execution site he selected a copse of half-grown pine trees located some 3-5 km from the Trostinez estate [Gut Trostinez]. With the Trostinez estate is meant a former kolkhoz which was taken over and put in use by the KdS department in April 1942. It was located some 15 km southeast of Minsk and could be reached by the Minsk-Smilovichi-Mogilev road, from which a branch road led some hundred meters south to the estate. Seen from the estate the pine copse was located across the road to Smilovichi. In order to reach it from the estate one had to first return to the road, then follow it for some kilometers in the direction of Smilovichi, and finally use a dirt track diverting to the north, which passed immediately by the copse. It was thus located remote from any human settlement and was from a distance hard for the eye to penetrate.

Through close contacts with the responsible Haupteisenbahndirektion Mitte in Minsk, where the KdS kept a liaison man, it was seen to that the exact arrival time of each transport, by hour and minute, was communicated in due time, either in writing or by telephone. As a first measure a pit of sufficient size was excavated in the copse near the Trostinez estate. The dimensions of these pits varied. They were up to 3 meters deep and wide and up to 50 meters long. For the excavation of the pits Russian prisoners of war were brought in from a prison administered by the KdS. This work took several days.

The executions themselves were carried out following a ‘framework plan’ drawn up by SS-Obersturmführer Lütkenhus. The deployment of the men at each operation followed the pattern of this plan. To each ‘center’ [Schwerpunkt] was assigned special commandos under the leadership of a Führer. All in all some 80 to 100 people, including men from the Schutzpolizei and Waffen-SS members, were used for the various tasks. […]

The course of an execution always followed an unchanging schedule, so that soon everyone involved knew his task in detail and performed it without needing any further instruction. In general the executions lasted from early morning to late afternoon. By having most of the transports arrive between 4:00 and 7:00 in the morning it was ensured that the deportees could be killed without any further delay – some of them already a few hours after their arrival.

One group of KdS members saw to it that the unloading of the arriving people and their luggage was carried out orderly. After that the arrivals had to proceed to a nearby collection point. There another commando had the task of stripping the Jews of all money and valuables. For this purpose there were also body searches.

At the collection point other members of the department searched out such people who appeared fit for work on the Trostinez estate. Their number varied between 20 and 80 at the most.

By the first eight transports, up to and including that of 24 July 1942, the unloading, collection and selection were carried out at Minsk freight station. From a loading site at the edge of the collection point the Jews departed on lorries for the grave site some 18 km away. In order to avoid that more than one vehicle arrived simultaneously at the execution site – something which may have given the people courage to openly resist – the lorries departed with a certain interval between them. This was seen to by a member of the department at the loading site.

From the arrival of the ninth transport on 10 August onwards, the trains were led to the immediate vicinity of the Trostinez estate. For this purpose the Reichsbahn directed the trains via the Minsk freight station to the locality of Kolodishchi, some 15 km to the northeast,[33] from where a closed track ran in southward direction. The track, which previously had ended in Michanoviche, now ended some hundred meters to the north of the Trostinez estate, on the hither side of the Minsk-Smilovichi road. Once disembarked, the Jews were collected in a meadow some 100 m away, and after the selection of labor for the estate were taken to a nearby loading site, from where they were sent to the graves a few kilometers away. Sometimes they had to cover this distance on foot.

In the beginning the prisoners on the deportation trains were shot. […] According to the length of the pit up to 20 shooters were placed out. During the course of an execution they were replaced with people from the cordon unit, which formed a loose cordon around the site. One always used pistols. Prior to the start of the operation each shooter received, as a rule, 25 bullets. This handing-out took place without any formalities, and there was no quittance. If a shooter needed more ammunition he went to the ammunition box placed near the pit and had it handed to him by the armory private or simply took it himself. For the killing, shots to the neck were used. If there was suspicion that a victim had not been fatally hit, additional shots were fired, but mostly one simply fired a submachine gun into the pit, until there were no more motions. No further precautions were taken before the grave was filled in to ascertain whether all people therein really were dead.

From around the beginning of June 1942, one also employed gas vans for the killings. The KdS department had at its disposal three such vans, one larger Saurer van and two somewhat smaller Daimond [sic] vans. […] The gas vans were equipped with a box-shaped mounting, which made them look like furniture moving vans. Inside they were covered with sheet metal. The only opening was the double wing door at the back. A small fold-out stair was used to make the loading procedure easier. Once deployed, the vans first drove to the loading site, which as mentioned above initially was located near the Minsk freight station and later near the end of the railway spur at the Trostinez estate. There the victims were summoned to step up into the vans. These were always loaded so full that the humans stood packed together. Thus up to 60 people could be crammed inside. After the doors had been closed the prisoners were completely surrounded by darkness and sealed off hermetically [luftdicht abgeschlossen] from the outside world. The gas vans now drove to the execution site, where they stopped close to the pit. Only then the extermination procedure commenced. The driver or his co-driver attached a hose [Schlauch] and led it so that the exhaust gases from the engine, which was running at light throttle, were led into the interior of the halted van. Panic soon broke out among the prisoners. In their death anguish they trampled each other and screamed or beat their fists against the walls. Due to this the vehicle swayed from one side to the other for the duration of a few minutes. After some 15 minutes the van stood still and quiet, a sign that the death struggle of the locked-in people had ended. First now the doors were opened. The corpses standing immediately by the opening generally fell out by themselves. The others were pulled out by a special commando of Jews or Russian prisoners and thrown into the pits. The interior of the van offered a terrible view. The corpses were soiled all over with blood, vomit and excrements; on the floor lay spectacles, dentures and tufts of hair. It was therefore always necessary to thoroughly clean the van before it was used. This was usually done in a meadow in the immediate vicinity of the Trostinez estate. The delays caused thereby, as well as frequent malfunctions may have been the reason why the vans were not always employed, so that the shootings of Jews continued.

So as to dispel any possible mistrust among the newly arrived Jews, Kommandeur Strauch assigned a member of the KdS department to hold a reassuring speech. An SS-Führer or Unterführer greeted them at the collection point and declared that they were being ‘resettled’ on the order of the Führer and that they would be sent to work on agricultural farms until the end of the war. It seems that most of them trusted those words. In any case the victims always stepped up into the gas vans or lorries quietly and calmly. A corresponding camouflage language was commonly employed, for example in official writings, where executions were called ‘settlement’ [Ansiedlung] or ‘resettlement’ [Umsiedlung] and the execution sites ‘settlement areas’ [Siedlungsgelände].”

As for the partial extermination of the Minsk ghetto inmates at the end of July 1942 the only documentary evidence introduced was the Nuremburg document 3428-PS, a letter from Generalkommissar Wilhelm Kube to Reichskommissar Hinrich Lohse dated 31 July 1942 in which it is stated that 6,500 Jews from the “Russian Ghetto” and 3,500 Jews from the so-called “Hamburg Ghetto” had been liquidated on 28-29 July.[35] The court ruled, however, that the figure mentioned by Kube “possibly may not be completely reliable” and instead pronounced a minimum of 9,000 victims. Again deviating from the documentary evidence introduced, the verdict stated that the extermination had lasted from 28 to 30 July, and further ruled that on each of these three days, “a minimum of 2,000 and a maximum of 3,500 people were delivered to their death”.[36]

According to the verdict there were “at least” 6,500 Russian and Reich German Jews left in Minsk on 1 September 1943. These were now taken out from the ghetto and interned in an SS labor camp in Minsk (the “Shirokaya Street camp”). The figure of 6,500 remaining Jews was reached by the court in the following manner:[39]

“At the beginning of 1942 the Minsk Ghetto was occupied by some 25,000 people, of which 18,000 were Russian and some 7,000 German Jews as well as Jews from the western territories [Westgebieten, with this is likely meant the small number of Jews from Brno (Brünn) in the Protectorate which departed for Minsk on 16 November 1941]. The number of the Russian Jews derives from an undated report written by SS-Obersturmführer Burkhardt with the title ‘Judentum‘ [Jewry], which likely dates from January 1942 and formed the basis of a major Einsatzbericht of the Einsatzgruppe A, the so-called ‘Undated Stahlecker report’.[37] As Burkhardt at that time was the referee for Jewish affairs at the [local] KdS department and thus involved with issues relating to the ghetto, his statements are particularly authoritative and probative. The number of Jews deported from the west to Minsk is confirmed by numerous documents, in particular transport lists. […]

Of these some 25,000 people at least 3,000 were killed in the March Aktion in 1942 and at least 9,000 during the July Aktion, that is in total 12,000 Jews. Accordingly there should still have lived 13,000 people in the Ghetto following the July Aktion. In fact, however, there were left only 8,600. This is confirmed by a writing from Generalkommissar Kube to the Reich Ministry of the Occupied Eastern Territories dated 31 July 1942 [the above-mentioned 3428-PS]. We further read in this that of the 8,600 remaining Jews 6,000 were Russian and the remaining [i.e. 2,600] Jews who had been transported to Minsk from the western territories. […]

We have no documentary evidence for the number of people killed in connection with the liquidation of the ghetto. The last communication which allows for a conclusion in this respect derives from April 1943. In a review presented by the Government head inspector [Regierungsoberinspektor] Moos of the Labor department [Arbeitsamt] of the city of Minsk[38] it was reported that ‘according to [the number of] issued identification cards’ 8,500 Jewish laborers had been registered. Since at the July Aktion in 1942 all Jews unfit for work had been killed, the 8,500 laborers mentioned by Moos corresponded to the total number of Jews living in Minsk.”

Based on a number of witness testimonies the court further concluded that between April and October 1943 a maximum of 2,000 Jews had been killed during smaller killing operations.[40] Hence some 6,500 Jews remained at the time of the liquidation of the ghetto.

The verdict states:[41]

“After some 14 days a convoy of some 1,000 men was prepared in the labor camp, which was then brought by train to Lublin to work there. There are certain indications that a second transport, consisting of Jewish women, likewise was dispatched to the western territories.”

Accordingly, some 4,500 Jews remained in Minsk at the beginning of October 1943. Of these all but a maximum of 500 were then brought during the following months to Trostenets in groups of 500 people each and killed there.[42]

The problem is that the verdict’s description of the ghetto liquidation does not hold up to scrutiny. In a list of 878 Minsk Ghetto inmates dating from 1943 no less than 227 are children between 2 and 15 years of age (85 of them 10 years old or less), that is, more than one-fourth; also listed are about a dozen of elderly persons, including an 86-year-old.[43] The claim that all ghetto inmates unfit for work were killed in July 1942 is thus demonstrably false, and the 8,500 Jewish laborers to whom cards had been issued in early spring 1943 accordingly could not have corresponded to the total number of inmates present in the ghetto at that time.

There is also much testimonial evidence indicating that more than just two Jewish transports departed from Minsk in September 1943:

- The witness Schlomo Lajtman affirms that he was deported from Minsk to the Sobibór “death camp” on or near 15 September 1943. The train took four or five days to reach Sobibór.[44]

- Another transport from Minsk to Sobibór departed on 18 September 1943 and arrived on 22 September. Among the 2,000 deportees were Arkadij Wajspapir, Semjon Rosenfeld and also Alexander Pechersky, who led the Sobibór prisoner revolt on 14 October 1943.[45]

- According to the witness Wajspapir a third transport from Minsk arrived in Sobibór a few days after his own.[46] The witness Yehuda Lerner, who was also deported from Minsk, states that Pechersky was already in Sobibór when he arrived there.[47] According to Lerner his transport arrived in Sobibór via Lublin and Chelm.[48]

- According to a diary kept by Helene Chilf, an inmate of the Trawniki labor camp in the Lublin District, two transports arrived at Trawniki from Minsk via Lublin between 16 and 19 September 1943. On the second transport was a Jewess by the name of Zina Czapnik, who after the war testified that she and 400-500 other Jews, including her husband, had been sent first to Sobibór, where 200-250 people, including herself, were selected for Trawniki.[49] Judging by the dates, the two transports mentioned by Chilf could not have been the same as the two abovementioned convoys departing Minsk on 15 and 18 September (provided that it indeed took four or five days for the transports to reach Sobibór, as attested by the witnesses A. Pechersky and Boris Taborinsky).

- The German Jew Heinz Rosenberg, who was deported from Hamburg to Minsk in November 1941, states in his memoirs that he and 999 other Jews were deported from Minsk to Treblinka on 14 September 1943. On arrival in the “death camp” Rosenberg and 249 other skilled workers were separated from the rest and sent by train to a labor camp in Budzyn.[50] The station master Franciszek Zabecki confirms in his memoirs that a Jewish transport from Minsk with the code “PJ 1025” and consisting of 50 wagons arrived in Treblinka on 17 September 1943 and was sent on from there “to Chelm (in fact to Sobibor)”.[51] None of the Sobibór witnesses deported from Minsk to that camp speaks, however, of a transport from Belarus arriving via Treblinka. It seems logical to assume that Rosenberg and Zabecki are speaking of the same transport, yet the number of wagons mentioned by the latter clearly implies a number of deportees greater than 1,000.

- Marie Mack, who was deported from Vienna to Belarus on 27 May 1942 and was detained for over a year in Trostenets, has stated that at an unstated date in September 1943 she and 999 other Russian and German Jews were deported from Minsk to Lublin. After spending several weeks in the Lublin concentration camp (Majdanek) she was sent on to other labor camps.[52]

It thus seems most likely that the number of Jews evacuated from Minsk to Poland in September 1943 far exceeded the 2,000 mentioned in the court verdict and may have amounted to 6-7,000 or even more. Accordingly one would have to doubt either the claim that 4,000 Jews were murdered in Trostenets following the ghetto liquidation, or the Kube letter from 31 July 1942 (3428-PS) which has it that only 8,600 Jews remained in Minsk at that time.

In 1999 German historian Christian Gerlach revised the number of Jews still present in Minsk at the beginning of the liquidation of the ghetto to some 10,000, while mentioning a witness (H. Smolar) stating that as many as 12,000 Jews lived there (including persons in hiding).[53] Based on numerous testimonies Gerlach lists the following six transports departing from Minsk: 1) a convoy of 1000 people, including 300 young men from the German ghetto and 480 Trostenets inmates, departing on 14 or 15 September for Lublin and the Majdanek camp – likely the same as Marie Mack’s transport; 2) the convoy of 2,000 Jews departing for Sobibor on 18 September that included A. Pechersky; 3) a transport with an unstated number of male Jews which reached Sobibor 16-19 September; 4) a transport of 450-500 Jewesses bound for Sobibor, of which part was selected for Trawniki (the convoy of Zina Czapnik); 5) the transport witnessed by F. Zabecki that arrived in Treblinka on 17 September; 6) a transport of German and Russian Jews to Auschwitz, likely at the beginning of October 1943. According to Gerlach’s estimate the total number of evacuees numbered at least 5,500, possibly as many as 7,000.[54] Still Gerlach does not acknowledge two convoys for which there is reliable testimonial evidence: the first of the transports to Trawniki noted in H. Chilf’s diary, and the third transport to Sobibór attested to by Lerner and Wajspapir. According to historian Wolfgang Curilla there further departed a transport with Byelorussian and German Jews from Minsk to Auschwitz at the beginning of October 1943.[55] [His minimum figure is thus almost certainly too low. In one of Gerlach’s footnotes we learn that, according to a testimony left by a German official named Erich Isselhorst in 1945, the number of Jews deported from Minsk and Baranovichi to Lublin between August and October 1943 had amounted to 12-13,000.[56]

As a consequence of his upward revision of the number of evacuees, Gerlach maintains that “the number of Jews killed in Minsk or Trostinez in September and October 1943 may not have been as high as previously estimated”. Here he points to contradictions in the statements left by the alleged perpetrators. Adolf Rübe, for example, declared in 1948 that only some 500 Russian Jews had been shot, and these due to logistical problems. When interrogated again in 1959 Rübe had upped the number of shot Jews to 4,000.[57] Ironically Gerlach manages to contradict himself, as elsewhere in his book he estimates that some 5,000 Jews were shot in Trostenets in connection with the ghetto liquidation.[58]

Characteristically Gerlach has tucked away his most important find in a footnote, wherein we learn that a preserved rationing coupon shows that “In October there were still at least 3,111 recipients of food rationing coupons in the so-called Russian Ghetto”.[59] This means that after at least 5,500-7,000 (but more likely some 7,500-9,000) Jews had been evacuated from Minsk and an unclear number of others shot, there were still at a minimum 3,111 Jews left in the main ghetto. How many more Jews could there have been in the “Sonderghetto” of the foreign Jews and in the city’s labor camps and prisons? Gerlach’s figures imply that there were at the very least some 10-12,000 Jews still present in Minsk at the beginning of September 1943. How does this fit with Kube’s statement that only 8,600 Jews remained in Minsk at the end of July 1942?[60] The inconvenience that the evidence presented above causes mainstream historiography may be surmised by the fact that when Israeli historian Yitzhak Arad presented his comprehensive historiography on the holocaust in the occupied Soviet Union in 2009, he simply omitted most of it, asserting instead that on the eve of the liquidation there had lived only some 2-3,000 Jews in the Minsk Ghetto, of which some hundred managed to survive.[61]

Whereas the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission claimed that 6,500 people had been shot or burned alive at the Trostenets estate during the last days of June 1944 (cf. §2.1.), the Koblenz court estimated only some 500 deaths at Trostenets for this period, most of them Jewish skilled workers still remaining in Minsk and at the estate.[62] Gerlach on the other hand has it that part of the skilled Jewish workers still remaining in Minsk in June 1944 were deported to Auschwitz.[63]

Since the Koblenz court did not treat the alleged mass killings at Trostenets as a separate-case complex, it did not pronounce a victim figure for the camp. Among the nine cases of mass killings treated within the scope of the trial, four pertained to Trostenets:

| Transport operations 11 May – 9 October 1942 | 13,500 |

| Partial clearing of the Minsk Ghetto, 28-30 July 1942 | 9,000 |

| Liquidation of the Minsk Ghetto, autumn 1943 | 4,000 |

| Final executions during the evacuation of Minsk, end of June 1944 | 500 |

| Total number of victims according to the verdict: | 27,000 |

The trial ended with the main accused Heuser being sentenced to 15 years in prison, while the ten other defendants were handed down prison sentences varying from 3 years and 6 months to 10 years.

2.4. H.G. Adler (1974)

In 1974 H.G. Adler published a study on the Jewish deportations from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate with the title Der verwaltete Mensch (The Administered Person), in which we find the following brief description of Trostenets:

“In a small village, which before the occupation had constituted a kolkhoz, the camp [Trostenets] was located; to this belonged an estate of 250 hectares. Here the prisoners were also housed, first in pig sties, later in barracks which each housed 150 to 160 people. During 1942 a total of 39,000 Jews from Germany, Austria, Bohemia-Moravia, Luxembourg, Holland and also from the Soviet Union were brought to Trostinetz, but in the camp itself there were never more than 640 Jews at one time, most of them Jews from Vienna; among the inmates there were also some hundreds of Russian prisoners of war.”[64]

The contention that Jews from Luxembourg and Holland were detained in the Trostenets camp goes completely against orthodox historiography, which has it that no Jews from these countries ever reached farther east than Poland. Adler moreover maintains that the five transports departing from Theresienstadt in October 1942 were sent to Trostenets instead of Treblinka.[65] The source for this contention appears to be the testimony of a certain Isak Grünberg, who was deported from Vienna to Trostenets on 5 (or 7) October 1942, who speaks of transports from Auschwitz, and hints at transports from Theresienstadt via Treblinka.[66] Grünberg estimated the number of Trostenets victims at more than 45,000.

2.5. Miroslav Kárný (1988)

In 1988 the Czechoslovakian historian Miroslav Kárný published an article discussing the fate of the Jewish convoys that departed from the Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto in the summer and autumn of 1942. His description of Trostenets[67], including the transports sent there from Theresienstadt, conforms with the verdict of the Koblenz trial against Heuser et al, which is indeed his main source on this subject. In a footnote Kárný dismisses as unfounded Adler’s 1974 hypothesis that the five transports sent from Theresienstadt in October 1942 were murdered at Trostenets instead of Treblinka.[68]

2.6. Paul Kohl (1990)

In 1990 the German journalist Paul Kohl published a book on the Belarus holocaust titled Ich wundere mich, daß ich noch lebe (I’m Amazed That I’m Still Alive) which was republished in 1995 under the new title Der Krieg der deutschen Wehrmacht und der Polizei 1941-1944 (The War of the German Army and Police 1941-1944). This book is partly a collection of testimonies, partly a travel journal which describes Kohl’s own visits to various museums and (alleged) mass killing sites, among them Maly Trostenets:[69]

“We drive back to the Minsk-Mogilev road and turn left after a couple of kilometers, onto a country road. We are going to the Blagovshchina pinewoods. From autumn 1941 to autumn 1943 this was the actual execution site. I want to see what can still be discerned of the 34 graves that were discovered here in 1944. But we don’t get far. Today the area is a military off-limits zone. In front of us is a sign with the inscription: ‘Do not proceed! Live rounds will be fired!’

So we go back in the direction of the village of Maly Trostenez, along the former camp site, towards the Shashkovka copse. 500 meters from the camp, at the edge of this copse, there has been raised a second memorial stone, likewise surrounded by an iron grating. To the left of it, in the woods, there once stood the Shashkovka oven, in which from autumn 1943 to the end of June 1944 the bodies of those shot here or killed in gas vans were incinerated. The outlines of the gigantic pit of the oven can only be guessed at underneath the brushwood.”

This description begs two important questions: Why was the area with the alleged 34 mass graves at Blagovshchina made an off-limits area by Soviet authorities? And what happened to the – apparently more or less intact – “incinerator” that the investigators of the Extraordinary State Commission reportedly discovered at the Shashkovka? When were the remains of it removed, and why?

Then follows Kohl’s brief history of the Trostenets camp:[70]

“From May 1942 onward, all executions took place in Blagovshchina. 20 shooters were placed along the length of each grave pit. One always used pistols and killed with shots in the neck. If there was reason to believe that any of the victims were still alive one simply fired with machine guns into the graves, until everything was still and quiet.

In the summer of 1942, a railway station was built by a one-way track near the collection point in the part of the camp closest to the [Minsk-Mogilev] road (the railway line had previously ended at Michanowice). The trains with Jews from the Reich, which had previously stopped at the Minsk freight yard, were now immediately redirected from there to Trostenez. Twice a week trains arrived from the Reich, from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, France. They arrived on Tuesdays and Fridays and – in order to avoid commotion – always in the early morning between four and five o’clock. Also from the Dachau Concentration Camp a train arrived in June 1942.

The arrivals were taken to a collection point two hundred meters away and there given a friendly reception. After all one had told them in connection with their arrest and departure something about ‘resettlement’, and one sought by all costs to avoid panic. The work had to be carried out orderly and frictionless in order to ensure the efficiency of the process. From the deportees were confiscated their identity cards, documents, gold and jewelry, as well as the 50 kilos of luggage that each deportee was allowed to bring with him or her for the purpose of ‘resettlement’: trunks, bags, blankets, kitchen utensils, coats, playthings for the children. One took all of this away from them under the pretense that they would receive new papers and that, for the sake of comfort, the luggage would be forwarded to them. When it was handed over the Germans even handed out receipts, so that many of them actually believed in the resettlement story until their last moment. Then a selection of the deportees took place into those fit and unfit for work. The first group was then divided among various specific professions: electricians, metalworkers, carpenters, tailors, and so on. For the unfit for work the gas vans were standing ready nearby, camouflaged as trailer homes with windows mounted on and mock-up chimneys attached to the roofs. Those fit for work had to carry on working their various professions until they were no longer fit.”

As for the total number of victims, Kohl sticks with the Extraordinary State Commission figure of 206,500.[71]

The bizarre notion that the gas vans employed in the killing of the victims were camouflaged as trailer homes is lifted from the highly spurious so-called Becker document, which has been discussed in detail elsewhere.[72] That Jews were deported by train to Trostenets not merely from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate but also from Poland and France goes completely against the orthodox version of events, and the assertion that the transports arrived twice a week, on Tuesdays and Fridays, also clashes with mainstream historiography.[73] Later in this article I will return to the claim that the arriving deportees were deceived by the Germans into thinking that they would merely be resettled.

German holocaust historian Christian Gerlach has commented thus on Kohl’s book:

“Paul Kohl is definitely one of the best experts when it comes to the camp complexes in and around Minsk […]. His statements are, however, […] often insufficiently documented and verifiable.”[74]

This may be to put things too kindly. In fact Kohl rarely provides any proper references, and they are particularly lacking when it comes to Kohl’s more extraordinary statements. I have managed, however, to track down Kohl’s source on the nationality of the deportees, a testimony from a certain Ernst Schlesinger[75], who claims to have been deported from Dachau to Trostenets in June 1942, a transport unknown to mainstream historiography:[76]

“Beginning in the spring of 1942 there arrived at Trostenets twice a week, usually on Tuesdays and Fridays, convoys with citizens of foreign countries – Austria, Poland, Czechoslovakia, France and Germany – that were brought in for destruction. Sometimes the trains would arrive at the station in Minsk, but more often a special railway branch brought the condemned to the very vicinity of Trostenets. The convoys usually arrived between 4 and 5 in the morning. The deportees were unloaded, had all their things taken away and were then given a receipt, so that they would not worry about their fate. The receipts made the condemned believe that they would be relocated to a new location.”[77]

2.7. Hans Safrian (1993)

In his book Die Eichmann-Männer from 1993, holocaust historian Hans Safrian mentions H.G. Adler’s 1974 hypothesis of the five October transports from Theresienstadt as plausible, while also referencing Grünberg’s statements.[78] Safrian estimates that at least 30,000 Western Jews and a vague “tens of thousands” of Belorusian Jews were murdered at Trostenets. He arrives at the first figure by assuming that all transports sent to the Minsk area from Central Europe in 1942 – “21 transports” with “over 25,000 men, women and children from Terezin, Vienna and Cologne” – together with some additional, undocumented transports in the same year (likely meant are the five October transports from Theresienstadt) were murdered at Trostenets.[79]

2.8. Christian Gerlach (1999)

In 1999 the German holocaust historian Christian Gerlach had his voluminous doctoral dissertation on policies of forced labor and (alleged) extermination in German-occupied western Belarus published under the title Kalkulierte Morde (Calculated Murders). In this the camp at Maly Trostenets is discussed in a brief subchapter on “death camps” in Belarus:[80]

“The most well-known and important of the camps was certainly Maly Trostinez, located some 12 kilometers southeast of Minsk. Its origin has not been fully clarified. According to Paul Kohl the extermination site Blagovshchina was sought out in November by the first head of KdS Minsk, Erich Ehrlinger, and used from that time on. The fact is that the first clearly provable execution at this site did not take place until 11 May 1942. As late as the Ghetto Aktion in Minsk at the end of July 1942 only a part of the victims were killed in Maly Trostinez, while others were murdered in Petrashkevichi at the other side of the city. Despite the so-called Heroes’ Cemetery, a memorial stone for Heydrich and settlement plans of [Eduard] Strauch, Trostinez always remained a provisory installation. […]

Nevertheless there exists a credible witness statement according to which a camp operated by the KdS existed near the village Maly Trostinez already in January 1942. The place, however, was not made into a major extermination site until Strauch took command. In March or April 1942 KdS was given the ownership of a kolkhoz of 200 hectares to be used as a country estate. Here a cattle farm was constructed in May 1942. […] The inmates of the camp were Jews and non-Jews, most of the latter were alleged partisans. Initially most of the Jewish inmates were Czech or German – between 20 and 50 Jews were picked out from each of the deportation convoys in 1942 and brought to the camp. Later there were also Belorussian Jews among the inmates. The number of detainees may have varied between 500 and 100; after the [Minsk] ghetto liquidation in October 1943 they numbered 200. Figures according to which there were 5,000 inmates in the camp at this time are not reliable.

The inmates of Trostinez were forced to work inside the camp itself, either with farming or as artisans […] apparently mainly to meet the needs of members of the KdS; some inmates were sent over during the day from Trostinez to buildings in Minsk. In the camp itself there apparently existed installations run by Organisation Todt and the Reichsarbeitsdienst that possibly employed camp inmates. All in all, however, the economic importance of the camp was marginal.

The official number of victims murdered in Trostinez and its vicinity amounts to 206,500. Such figures – immediately after the war even as many as 546,000 victims were claimed – appear far too high in the light of presently available research. An attempt at reconstruction gives approximately 40,000 victims as well as an additional unknown number of prison and camp inmates from the vicinity of Minsk, who had been arrested during roundups and anti-partisan operations. Exact figures are impossible to provide, as the mass graves were exhumed and the corpses burnt by the German Sonderkommando 1005 starting October 1943. Statements from people involved in this procedure nonetheless indicate that somewhere between 40,000 and 50,000 dead had been interred in the mass graves. The reports of the investigative authorities from 1944 gave approximately 150,000 or up to 150,000 victims, but even this figure is well too high. In total – as a rough estimate – 60,000 people could have been exterminated at Trostinez.”

In a footnote Gerlach elucidates on his own victim estimate:[81]

“The figure 40,000 is constituted as follows: some 5,000 victims from each of the ghetto Aktions in July 1942 and autumn 1943; some 20,000 Jews deported in 1942 from Central Europe for extermination at Trostenets; 3,000 so-called suspected bandits [Banditenverdächtigen], who were gassed during ten days in February 1943, and 6,500 victims of the massacres on camp and prison inmates at the time of the German retreat at the end of June 1944.”

This revised victim figure is of crucial importance for the exterminationist understanding of the function of the camp. If it is correct then 80% of the victims during the first year of operation (1942) were Jews deported from Austria, Germany and the Protectorate. This clearly implies that Maly Trostenets was set up especially to handle such transports. Up until the publication of Kalkulierte Morde Trostenets had primarily been viewed as an extermination center for Belorusian Jews and secondarily as a site for the killing of Jews from Central Europe (Hans Safrian’s book from 1993 being a possible exception). Gerlach reversed this view by way of allocating most of the (alleged) mass murders of Minsk Jews to other, even less known killing sites around Minsk.[82]

Another noteworthy aspect of Gerlach’s victim figure is that he has conflated the alleged gas van murders and mass shootings at the Shashkovka site carried out from October 1943 onward, the victims of which were supposedly cremated in some type of field oven, with the 6,500 victims from June 1944 which the ESC in their September 1944 report claimed had been burnt alive inside barns and on “piles of logs” in the camp itself.

Finally it should be noted that while Gerlach is familiar with Isak Grünberg’s testimony[83], he refrains from mentioning that this eyewitness spoke about convoys from Auschwitz and hinted at transports from Theresienstadt via Treblinka in October 1942. Significantly Gerlach devotes another subchapter of his book[84] to presenting a large number of testimonies about the presence of Dutch, French and Polish Jews in Minsk and other locations in Belarus, without going into any detail as to how these Jews arrived there – clearly because this would lead to the uncomfortable conclusion that they were sent there via the “extermination camps” in Poland. As for the presence of Polish Jews in Trostenets we learn:[85]

“It is a fact that many Polish Jews were detained at Trostinez, apparently under the command of Organisation Todt. 250 of them were later transferred to the SS Construction Office in Smolensk.”

As source for this Gerlach refers to four witnesses (the Germans “H.W.” – who worked at the SS Central Construction Office Russia Center (SS-Zentralbauleitung Rußland-Mitte) – and Karl Buchner, the Jews “E.S.” – likely identical with the abovementioned Ernst Schlesinger – Anna Krasnoperko, and an unnamed witness referenced by H. Safrian). Isak Grünberg likewise testified that many Polish Jews had been detained at Trostenets at the time of his arrival.[86]

2.9. Marat Botvinnik (2000)

In 2000 the Belarus historian Marat Botvinnik published a slim book on the holocaust in Belarus in which Trostenets is devoted a short chapter. Here we read:[87]

“Near the village of Trostenets, located 11 km from Minsk along the Minsk-Mogilev highway, the Nazis created the so-called labor camp Blagovshchina. Under this false guise was operated a death camp which had access to the railroad […]. In a concentration camp near the village of Trostenets the Nazis systematically slaughtered between 1941 and 1944 hundreds of thousands of people, many of whom were Jews from Minsk and other locations in Belarus. Others were political prisoners kept by the Germans, or Jews from the cities of Austria, Germany, Poland and Czechoslovakia. Most of the victims were women, children and old people. Some of them were brought in vans that were colloquially known as ‘black ravens’ or ‘gas vans’. The victims were suffocated by exhaust gases, and their corpses unloaded at a pre-dug pit in the Blagovshchina Forest. Many trains arrived from cities in Belarus and the countries of Western Europe. […] With two-faced courtesy the doomed were asked to surrender their valuables and belongings, for which in turn they were handed receipts. The hangmen created the appearance that they would be taken to work at another location. They were loaded onto large trucks with trailers that stood ready nearby and taken to the execution site, where they were ordered without any courtesy to undress and then shot.”

Mainstream historiography knows of no transports of Polish Jews to Trostenets, even though the presence of Polish Jews in the camp is supported by several witnesses (see the preceding paragraph). The claim that Jews from other Belorusian cities than Minsk were sent by train to Trostenets appears to be unique to this author.

The most interesting that Botvinnik has to say about Trostenets concerns the methodology of the Soviet investigators. After mentioning that both 546,000 and 206,500 had been officially stated as victim figure, Botvinnik (who champions a vague “hundreds of thousands” victims) explains:[88]

“The difference between the victim numbers stated in the documents can be explained by the fact that the investigators used different methods when counting the corpses in the grave pits: some estimated that each cubic meter of grave contained 20 corpses, some insisted on a density of 7 corpses, yet others on 5, thus giving rise to differing victim figures. Even former inmates who miraculously survived the camp can not give precise information about the number of people murdered by the Nazis.”

In other words, the investigators determined their victim figures based on apparently completely arbitrary estimates of the density of corpses in the 34 Blagovshchina mass graves, of which they had merely “partly opened” five (see §2.1.). The full repercussions of this methodology will be exposed in §3.2 of part 2 of this series.

2.10. Paul Kohl (2003)

It was only in 2003 that a book devoted exclusively to Trostenets appeared in a Western language. This slim[89] volume, titled Das Vernichtungslager Trostenez. Augenzeugenberichte und Dokumente (The Trostenez Extermination Camp: Eyewitness Reports and Documents) consists of three main sections: a 15-page history of the camp written by Kohl himself, a collection of (relatively brief) witness statements and documents relating[90] to various aspects of the camp (“The transport”, “The arrival”, “The camp”, “Blagovshchina”, “The gas vans”, “The disinterment”, “Shaskovka”), and a brief chapter of the post-war fates of the alleged perpetrators.

Unfortunately, Kohl’s new history on Trostenets is extremely derivative, so that the primary value of this volume lies in the testimonies and documents that it reproduces (many of which have been quoted and referenced elsewhere in this article). It is of interest, however, to note what Kohl does rehash from previous historiographical statements on the camp. Most importantly, Kohl has thrown overboard his own previous statement that Jews from Poland and France were deported to Trostenets (cf. §2.6.). He does not refer to the witness Ernst Schlesinger, nor does he mention Isak Grünberg.

There is, however, one significant new element introduced by Kohl in this book:[91]

“The number of forced laborers grew, the camp was enlarged, new barbed-wire fences and new guard towers had to be erected. In addition, the lorry convoys and the deportation trains daily brought in more people to be shot than the shooters could liquidate in one ‘work day’. For that reason the people had to wait two or three days for their death in bunkers and barracks, that were likewise surrounded by barbed-wire fences and guard towers. Thus were established two separate camps: One for the forced laborers working on the estate, the other for those waiting to be shot.”

Since Kohl’s essay on Trostenets lacks footnotes, and only has a bibliography, it is impossible to determine the source for this statement, but it seems likely to be derived from court material (it is not supported by any testimony or document presented in the second part of the book).

According to Kohl the shootings at Blagovshchina were carried out by “up to 20 shooters”, who worked on a rotating schedule (some 80 to 100 police and SS are said to have been present at the execution site). The Jewish convoys are stated to have arrived between 4 and 7 o’clock in the morning. The killing is said to have taken from early morning to late afternoon.[92] In addition “gas vans” were supposedly used with a maximum capacity of 60 or 80 victims, depending on type.[93] Now, Kohl accepts that the convoys from Austria, Germany and the Protectorate, which arrived with a frequency of one per week, each consisted of at most some 1,000 deportees, of which 20 to 80 were selected for work in the camp and a smaller number had perished on the way.[94] This would leave at most some 950 deportees to be shot. Each shooter – and for the sake of argument we will say that there were only 15 of them – thus had to kill at most (950 ÷ 15 =) 63 Jews. Considering the alleged highly organized form of the whole operation – according to the verdict of the Koblenz trial the shootings were carried out according to a detailed “framework plan” developed by a certain SS-Obersturmführer Lütkenhus of the KdS Minsk (cf. §2.3) – the alleged optional use of several “gas vans” (Kohl estimates that 1 van could kill 300 people in 1 day and asserts that in total 3 “gas vans” were employed at Trostenets[95]), the start in the early morning, and the revolving schedule of the shooters (which would eliminate the need for breaks) it would seem that the extermination of the convoys from the west could well have been carried out within a few hours, and most certainly within a day.

Kohl mentions only three instances of larger groups being killed at Trostenets: 1) part[96] of a group of 7,000-10,000 Jews from the Minsk Ghetto allegedly murdered at Blagovshchina in November 1941, i.e. before the establishment of the camp[97]; 2) some 10,000 Belorusian and German Jews from the Minsk Ghetto murdered at Blagovshchina during the three-day period of 28-30 July 1942[98]; 6,500 people shot or burned alive in the camp itself during its last days of existence (28-30 June 1944).[99] As seen above, Gerlach maintains that some 5,000 Jews were killed at Trostenets in connection with the liquidation of the Minsk Ghetto in the autumn of 1943. The first and third instances mentioned by Kohl clearly have no relevance for the construction of a separate “waiting camp” (due to their dating). Assuming that the massacres of Jews from the Minsk Ghetto in July 1942 and autumn 1943 really took place as alleged, there would have been two instances when the Jews brought to Trostenets possibly couldn’t be all murdered in one day – but would such isolated instances warrant the construction of barracks, bunkers and guard towers? Also, if we are to believe the Gruppe Arlt report of 3 August 1942, 6000 Jews from the “Russian Ghetto” in Minsk were all killed in a single day – 28 July 1942 – without the occurrence of any such “backlogging” (cf. §3.3.). And if such indeed had occurred, wouldn’t it have sufficed with a temporary holding pen consisting of a simple barbed-wire fence? In other words: the construction of a separate camp where deportees had to wait “two or three days for their death” makes precious little sense from an exterminationist viewpoint.

As for the total number of victims, Kohl chose to revive the 206,500 figure of the ESC, but in a rather half-hearted manner:[100]

“According to the investigations of the commission 150,000 people were murdered in the forest of Blagovshchina, 50,000 in the pit of Shashkovka and 6,500 people in the barns at the estate. The total number of people murdered in the Trostenez extermination camp amounted according to the commission’s statements from July-August 1944: 206,500.

Despite these statements there exists no certain evidence concerning the number of people actually murdered. The abovementioned total figure may be put into doubt. Perhaps it is speculation. Just like all other figures. However, as long as there is no other evidence available [pointing to a different figure] one must accept the figure reported by the commission.”

That Christian Gerlach four years earlier dismissed the ESC figure as “far too high” does not bother Kohl in the least – although it would appear that Kohl is unaware of Gerlach’s Kalkulierte Morde; at least he does not list it among his sources. In any case it hardly needs to be pointed out that Kohl’s reasoning here is deeply flawed: Confronted with the claim that X number of people have been murdered, the logical response from any sane, rational person would be to ask for hard evidence supporting that this number of people has indeed been killed. One would not uncritically accept an unsubstantiated claim just because no evidence contradicting it was available.

It should perhaps not surprise that Kohl’s book is very lacking when it comes to source criticism. There is no discussion whatsoever with regard to the authenticity of the documents presented, nor any evaluation of the reliability of the eyewitnesses. Even though we encounter no patently outrageous tales of Nazi sadism, as we do in much other “death camp” literature, Kohl presents straight-faced a number of witness claims that strike the critically-minded reader as implausible or at least remarkably odd. Here it will suffice to give three examples: