The Number of Victims of Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp (1936-1945)

Every year on 22 April the liberation of Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp is duly commemorated. On this occasion, the press sometimes still mentions the figure of 100,000 victims who allegedly perished or were murdered at this camp. Although Sachsenhausen does not belong to the six “classic” extermination camps (Chelmno, Majdanek, Auschwitz, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka), the epithet of a “death camp” which was given to it by Soviet propaganda is sometimes still used. While the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site today contents itself with a death toll of “tens of thousands”, it has never publicly disavowed the propagandistic figure of 100,000 victims. One might speak of a “silent revision”: Certain Allied propaganda figures which arose during or shortly after the war are quietly jettisoned, but this fact is never publicly admitted, nor is there any discussion about the way these wildly exaggerated numbers arose.

So, how many people really perished at Sachsenhausen?

The Conclusions of the Soviet Investigating Commission

As early as 1942 the Soviet authorities had founded an ”Extraordinary State Commission“ (ESC) aiming at ascertaining “crimes” committed by the ”German fascist occupiers” and the damage caused by them. The activities of the ESC naturally extended to the German concentration camps that had been liberated by the Red Army. Thus a Soviet commission carried out an investigation at Sachsenhausen in May/June 1945, one of its tasks being the ascertainment of the number of victims of the camp.

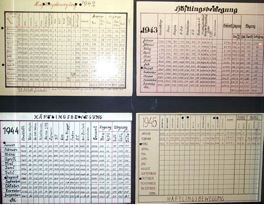

While the death books had been largely lost during the evacuation of the camp, the daily figures of prisoners present at roll call (Veränderungsmeldungen) has survived. With a few gaps, these documents covered the period from 1 January 1940 to 17 April 1945. Based on these figures, the Prisoner Records Office (Häftlingsschreibstube), which answered to the SS, had compiled monthly statistics of Prisoner Movement (Häftlingsbewegung). These documents, which were also captured by the Soviets, are now exhibited at the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site (Barracks 38), however they are falsely presented as statistics drawn up by former prisoners after the end of the war. As a matter of fact, the tables are contemporaneous with the camp’s operation and compiled at the Prisoner Records Office , which was subordinated to the Political Section (Politische Abteilung) of the SS.[1]

The Soviet investigators ordered three former prisoners, the Communists Walter Engemann, Gustav Schöning and Hellmut Bock, to audit the statistics. This was undoubtedly done in order to prove that the SS had falsified the statistics to “cover up their crimes”. The group, headed by Engemann, performed its task conscientiously, paying special attention to “exits without information” (Abgänge ohne Angaben). Altogether 3,733 such unaccounted “exits” were found, 2,448 of them concerning Soviet POWs, who had disappeared from the statistics of the camp on 22 October 1941. Of course this does not prove in any way that these POWs were shot.

For the years 1940-1945, Engemann, Schöning and Bock, based on the Veränderungsmeld-ungen, ascertained a figure of 19,900 prisoners who had died in the camp. This result largely confirmed the death toll reported by the SS. In a report he produced for the ESC in Moscow, the head of the Sachsenhausen Commission, Lieutenant Colonel A. Sharitch, adopted this figure. In 2003, Carlo Mattogno arrived at a slightly higher number (20,173).[2] This author (K.S.), who based his analysis on the Häftlingsbewegung data rather than the Veränderungsmeldungen and considered the whole period of existence of the camp (1936-1945), comes to the conclusion that Sachsenhausen claimed altogether 21,999 victims.

Which Figures Are these Reports Referring to?

In addition to the main camp, Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp comprised about 15 satellite camps and dozens of small outstations. In the pre-war period, only male prisoners were interned here, but during the war, thousands of female prisoners were deported to Sachsenhausen as well. Another category of detainees was the Soviet POWs. Which categories of prisoners do the above-mentioned statistics refer to: All prisoners, or only the male ones? The entire Sachsenhausen complex including the satellite camps or only the main camp? And what about the Soviet POWs? Engemann and his comrades do not even broach these important questions, and historians hardly ever discuss them either. However, a comparison with contemporaneous SS statistics of all prisoners in all concentration camps (a document dating from January 1945) allows us to conclude that the Veränderungsmeldungen and the Häftlingsbewegung referred to the entire camp including the satellite camps, but only to the male inmates.[3]

How Did the Figure of 100,000 Victims Arise?

The man in the Kremlin, who was responsible for millions of deaths in the GULAG and who had his propagandist Ilya Ehrenburg claim 4 million victims of Auschwitz before the Red Army had even entered that camp, was apparently not sufficiently impressed by the Sachsenhausen death toll. For this reason, the figure of 19,900 (or slightly more) victims never appeared in Soviet propaganda. Instead the number of 100,000 first appeared in October 1945 in a letter Professor I. P. Traynin, a member of the ESC, wrote to Foreign Minister V. Molotov. The letter begins abruptly as follows[4]:

“At the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin, the German authorities have annihilated more than 100,000 citizens of the USSR, England, France, Poland, Holland, Belgium, Hungary and other states.”

No explanation whatsoever is given for this laconic assertion. It is highly improbable that Traynin would have undertaken to issue such a statement without a hint from the very top – in other words, from Stalin himself. The figure of 100,000 victims was immediately spread by Soviet propaganda.

In late 1946 and early 1947, a ”forensic commission“ headed by one of Russia’s most illustrious pathologists, Professor V. I. Prosorovski, visited Sachsenhausen, but apparently did not carry out any further investigations. Prosorovski was no newcomer to this kind of activity: He had served as an expert for the ESC at the “war crimes trials” at Krasnodar[5] and Kharkov[6],[7] (1943), co-authored the Soviet counter-expertise at Katyn[8] (January 1944) and acted in the Katyn case as a witness for the prosecution at Nuremberg. It goes without saying that his forensic reports invariably confirmed the version of the ESC. As a citizen of the Stalinist Soviet Union, he had of course no other choice.

While the commission headed by Prosorovski adopted the figure of 21,700 victims which was based on the SS Häftlingsbewegung records and had been confirmed by Engemann and his team, they invented a plethora of additional groups of victims, making no attempt whatsoever to justify the figures adduced. The final death toll given by the commission was 100,000. This figure was adopted without any further ado by the Soviet military court that conducted the so-called “Berlin Trial”, where several members of the former SS garrison of Sachsenhausen were put on trial in Berlin-Pankow (October 1947). In 1961, when the “Sachsenhausen National Commemoration Site” was inaugurated by the East German authorities, a Book of Commemoration was published, where the 100,000 figure appeared three times: in the introduction, in a speech by Walter Ulbricht and in the “Cry of Sachsenhausen”. In the German Democratic Republic, this figure thus became a dogma nobody would dare to question.

The Soviet Prisoners of War at Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp

The number of Soviet POWs who perished at Sachsenhausen is still an unanswered question. Why were these POWs sent to a concentration camp in the first place and not to a “normal” POW camp – in their case, a “Russian camp”?

After their invasion of the Soviet Union, the Germans took hundreds of thousands of prisoners within the first few months (the exact number is still disputed). Sheltering and feeding this huge mass of people confronted the Wehrmacht with enormous problems. Those Soviеt POWs who were sent to the territory of the Reich before the onset of winter were relatively lucky. Since the capacity of the existing POW camps was insufficient to lodge them all, a considerable number of Soviet prisoners were sent to farms to perform agricultural work or to German towns to perform communal work. Thousands more were interned in concentration camps – not for annihilation, but in order to work in industrial plants situated in the neighborhood of the camps. The “normal” camp inmates had to evacuate some of their barracks for the newcomers, which led to serious overcrowding.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-K0901-014 / CC-BY-SA [CC-BY-SA-3.0-de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons

Typhus

The six “Russian barracks“ designated for the Soviet POWs at Sachsenhausen were named Kriegsgefangenen-Arbeitslager and strictly separated from the rest of the camp (Russen-isolierung). From an administrative point of view this sector was not a part of the concentration camp but became part of Kriegsgefangenen-Stalag Oranienburg instead.[9] Owing to the massive influx of POWs, the usual registration procedure which included delousing and 14 days of quarantine was apparently not observed, and within a short period of time typhus was rampant in the camp.

A separate register of deceased prisoners seems to have been maintained for the Stalag (Stammlager für Kriegsgefangene) since 22 October 1941. This document has not survived. The mortality among the Soviet POWs was staggeringly high. A surviving list[10] about the (presumably) first two Russian transports reveals a horrific death toll: In the period from 18 October to 30 December 1941 altogether 2,508 Soviet POWs had been admitted to Sachsenhausen; however on 30 December 1941 only 1,360 of them were still alive. In other words: 1,148 prisoners (46% of the total) had died within these two and a half months, most of them undoubtedly from typhus.

The “Russenaktion“

Communist functionaries, especially Political Commissars (Politruks), of which at least one was attached to every unit of the Red Army, were meted out a far worse treatment than “normal” Russian prisoners (Arbeitsrussen) because from the National Socialist point of view, these functionaries were “carriers of the Soviet regime”. According to the Kommissarbefehl issued by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht on 6 June 1941 at Hitler’s instigation, commissars were not recognized as combatants and were denied the protection they would be entitled to as POWs in accordance with international law. They were ordered to be shot after capture. To its credit, the Wehrmacht disapproved of the Kommissarbefehl from the very beginning and largely failed to implement it so that only a minority of the captured commissars were actually shot. With Hitler’s agreement, this order was effectively revoked on 6 May 1942.[11]

While the Kommissarbefehl concerned primarily the combat units, two special orders (Einsatzbefehle) issued in July 1941 by Reinhard Heydrich, chief of the Sicherheitspolizei and the SD, provided for the screening of the inmates of POW camps. The Germans had become aware of the fact that many commissars had mingled with the great mass of prisoners, their uniforms being indistinguishable from the ones of military officers or common soldiers but for a red star on the sleeve (which could easily be removed). Therefore the POWs in the camps were subjected to systematic interrogation. Those identified as commissars were “singled out” and sent to the nearest concentration camp to be shot. Both the Kommissarbefehl and Heydrich’s Einsatzbefehle were highly questionable measures and most likely illegal from the point of view of international law. As early as 15 November 1941, the two Einsatzbefehle were somewhat mitigated with Himmler’s approval: From now on, those singled out as commissars could be used for hard physical labor in the quarries instead of being shot.

It is not known when the shooting of Soviet POWs (Russenaktion) at Sachsenhausen began; the earliest date mentioned is late August 1941. Our knowledge is exclusively based on the statements of former prisoners (Büge, Sakowski etc.) which often contradict each other and were probably made under duress. In mid-November 1941 the Russenaktion was allegedly stopped, presumably for two reasons: The revocation of Heydrich’s Einsatzbefehle (15 November 1941) and the recent outbreak of typhus. Incidentally several German prisoners employed at the crematorium were among the first victims of the dread disease. During the Russenaktion they had sat on a heap of clothes belonging to shot Soviet soldiers and been infected by lice. Subsequently the camp was subject to a quarantine that lasted several weeks.

Soviet Propaganda

Efficiently exploiting the Russenaktion, the relatively bad living conditions in the camps and the frighteningly high mortality among “normal” Soviet POWs, Soviet propaganda insinuated that the NS regime deliberately exterminated its captured soldiers of the Red Army. Of course Moscow’s propagandists remained silent about the fact that the treatment of the Russian prisoners, who fared indeed much worse than Western POWs, was a direct consequence of Soviet policy. As early as 1919, the USSR had withdrawn from the 1907 Hague Convention, and the Soviet government never signed the 1929 Geneva Convention about the protection of prisoners of war. For this reason, the captured soldiers of the Red Army were not protected by these conventions, even if the universally recognized laws of humanity did apply to them.

After the liberation of the Sachsenhausen Camp Soviet operatives “fed” the former inmates with disinformation and atrocity propaganda about a huge slaughter of Soviet POWs. Rumors which had arisen during the war were now “confirmed” by “knowledgeable” former prisoners. German prisoners of war and prisoners of the NKVD were forced to make statements that they would never have made voluntarily. To what extent Soviet propaganda distorted the facts is demonstrated by the immensely exaggerated figures of victims bandied about by Moscow’s propagandists.

The Number of Allegedly Shot Russian POWs According to Witnesses

The Russenaktion was carried out in the northern sector of the Industriehof (industrial court) which was situated outside the camp triangle. A special part of the Industriehof was the so-called Holz- und Kohleplatz (wood and coal yard), which was protected from prying eyes by walls and buildings. According to the official history (which was later confirmed by former SS men before West-German Courts), the unsuspecting prisoners were marched into the barracks where they were placed in front of a supposed height-measuring device. Through an opening in the wall behind this device, the victim was killed with a shot in the back of his neck by a man standing in the adjacent room, various SS-Blockführer acting as executioners.

The bodies of the victims were incinerated in four field crematoria that had been installed in front of the barracks and were surrounded by a wooden fence. This grisly work was carried out by about eight German prisoners. The overwhelming majority of the inmates were not allowed to enter the northern sector of the Industriehof and had no possibility whatsoever to witness the killings: Whatever they knew was based upon rumors. As is to be expected under these circumstances, the “eyewitness reports” are literally teeming with improbabilities and contradictions. Nearly all “witnesses” claimed between 14,000 and 18,000 shooting victims, and some of them ventured even higher figures. In all likelihood, these “witnesses” had been instructed by Soviet operatives.

After the end of the war, at least two former prisoners seemed very well informed about the Russenaktion: Emil Büge, who had worked at the Prisoner Records Office where he had to register the admittees, and Paul Sakowski, who had been one of the crematorium workers. Both men left very detailed written reports about what had transpired at the camp, and Sakowski entered the witness stand at the Berlin Sachsenhausen trial. Both of them mentioned the usual figure of 14,000 or more shot Russian POWs. It stands to reason that they had no choice, each of them subject to the mercies of one of the victorious powers. According to his own statements, Büge had worked “for the Americans”, which most probably means the Augsburg-based U.S. War Crimes Commission. Lonely, impoverished and no longer needed by the Americans, Emil Büge committed suicide in 1950.

Paul Sakowski (born in 1920), whom East German propaganda christened “the hangman of Sachsenhausen”, was arrested by the NKVD shortly after his liberation from the camp. In October 1947, he was among the defendants at the Sachsenhausen trial at Berlin-Pankow. Sakowski was sentenced to 25 years, which he served until the very last day, first at Workuta and later in East Germany. As he had been previously interned at Sachsenhausen for six years, this man spent more than 31 years of his life behind prison bars.

The case of SS-Scharführer (Second Sergeant) Paul Waldmann starkly illustrates the means the Soviet agents resorted to in order to “prove” imaginary figures of victims. Waldmann, who had been a driver for the Oranienburg SS, was sent to the Eastern Front in December 1941 where he uninterruptedly served until the retreat of the German forces to Berlin. On 2 May 1945 he was taken prisoner by the Red Army near the “Zoo” Train Station[12] and transferred to Posen, where he was subjected to routine questioning. The fact that he had served at Sachsenhausen obviously aroused the interest of his interrogators. On 10 June 1945, Waldmann signed a “confession”, stating that the Russenaktion, in which he had allegedly participated, had claimed the lives of no fewer than 840,000 (!) Soviet prisoners. Although this preposterous figure was never put about by Soviet propaganda, it has survived because owing to an obvious error of the clerks in Moscow, it was filed among the Auschwitz documents (IMT Doc USSR-52) where it was rediscovered by Carlo Mattogno in 2003. Paul Waldmann disappeared without leaving any trace; presumably he met his fate in the GULAG. In February 1946, the clerks in Moscow had apparently not yet become aware of their error, because excerpts from Waldmann’s “confession” were read by Soviet prosecutors Pokrovski and Smirnov at Nuremberg and thus became part of the protocols of the Nuremberg trial as well.[13]

The Number of Shooting Victims – Official Statements

One of the earliest post-war documents about Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp is the so-called prisoners’ report (Häftlingsbericht) authored by Hellmut Bock. The report exists in seven or eight – more or less different – versions. The first version which was presumably completed on 7 May 1945 is now lost, but an English translation has remained.[14] There we read:

“September – December 1941. 16,000 Russian prisoners, driven together like cattle, were slaughtered. On the grounds of the industry-department four riding furnaces were standing so that the corpses could be cleared away uninterruptedly. Their ashes became the site for the new crematory. Before these people were murdered, they were beastly ill-treated. Music out of big loudspeakers deafened the shrieking of the victims.”

Although this earliest version of the report was modified several times, the number of 16,000 murdered Soviet POWs was still the same when Hellmut Bock submitted the final, seventh version of the report to the Soviet Investigation Commission.[15]

The head of the commission, Sharitch, slightly reduced this figure; on 30 June 1945 he wrote in his report:[16]

“In September/October 1941, 13,000 to 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war were shot.”

In the various drafts of the ESC about Sachsenhausen the figure of 14,000 shot Soviet POWs regularly recurs.[17] On the other hand, the commission headed by Professor Prosorovski[18] mentioned 20,000 shooting victims (January 1947), and in April 1961, when East Germany dedicated a National Memorial Site at Sachsenhausen, yet another figure (18,000) was claimed.

Since the collapse of East Germany, these figures have been somewhat reduced. On the occasion of the 56th anniversary of the camp’s liberation it was declared[19 ]:

“The so-called ´Station Z´, called so by the Nazis, was the annihilation site of the Concentration Camp with a neck-shot facility, gas chamber and crematorium. In Fall 1941 at least 12,000 Soviet POWs were shot here.”

Only four years later (2005) the Sachsenhausen Memorial Site wrote[20]:

“In the months from September to November 1941, the Wehrmacht transported at least thirteen thousand Soviet prisoners-of-war to Oranienburg, where the Concentration Camps´ Inspectorate organized the entire operation for the murder of Soviet prisoners-of-war. More than ten thousand of these were murdered within only ten weeks in an automated ´head shot´ facility.”

All these sources remained silent about the factual basis of their figures. Today, the official figures are obviously still based on the Soviet view of history as it was imposed after the War.

To the best of our knowledge, the only attempt to determine the number of Soviet POWs shot at Sachsenhausen with any degree of accuracy was made by the district court of Cologne (Köln) at the trial of Kaiser, et al. (1965).[21] However, the verdict freely admitted:

“It was not possible to ascertain the number of the shot Russians. There were no documents about this question.”

All the same, the court quoted two sources it considered relatively trustworthy: A compilation by the former Arbeits- und Rapportführer Gustav Sorge and a statement made by the former camp elder (Lagerälteste) Harry Naujoks who had been assigned to collect the identification tags of the Russian soldiers. Despite its initial reluctance to name a concrete figure, the court finally concluded:

“Considering the possibility of further imprecisions, we can assume now as certain, that during the action from begin of September to mid of November 1941 at least 6,500 Russian POWs have been shot in Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp.”

The Russian сommemorative stone

In November 2000 a relatively modest monument consisting of two black granite blocks was dedicated on the grounds of the former Sachsenhausen concentration camp by the foreign ministers of Russia and Germany, Igor Ivanov and Joschka Fischer. One of the stones bears a bronze plaque with the following inscription in Russian and German:

“1941-1945. Remember every single one of the thousands of sons and daughters of the fatherland who were tortured to death at Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. The Government of Russia.”

Thus no explicit figure was mentioned, apparently because neither side desired to identify with the propagandistic figures still publicized by the media (10,000 to 18,000). Whether authentic German documents about the real number of victims of the Russenaktion still exist today (in Moscow or elsewhere) remains to be seen.

Summary

In the nine years of its existence, Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp (including all satellite camps and outstations) claimed the lives of about 22,000 male prisoners. In view of the fact that approximately 140,000 male deportees were sent (and registered) to this camp, this means that 15.7% of the prisoners perished. Compared to prison camps of other states, other wars and other times, such a percentage is unfortunately nothing extraordinary.

This number does not comprise the female detainees who died in the satellite camps and the Soviet POWs who perished from “natural causes” or were shot. The real number of these victims deserves further research. It bears mentioning that 533 prisoners were killed during Allied air raids in 1944/1945. After the Auer factories at Oranienburg had been bombed on 15 March 1945, the dead bodies of 282 female prisoners were retrieved.[22] However, these tragic losses do not even remotely justify the propagandistic figure of 100,000 victims. As to the number of prisoners who perished during the evacuation of the camp (the inmates were marched away in various columns), the existing information is very incomplete. Obviously these deaths cannot be ascribed to the conditions in the camp. Just like the German refugees who died on their flight from the Eastern provinces to the West, these victims succumbed to the horrible conditions prevailing as a consequence of the invasion and conquest of Germany.

Abbreviations

| AS | Archive Sachsenhausen |

| BArch | Bundesarchiv Berlin (Federal Archive, Berlin-Lichterfelde) |

| FSB RF | Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation |

| GARF | Gosudarstvenniy Archiv Rossiskoy Federatsij (State Archive of the Russian Federation) |

| GULAG | Gosudarstvennaj Upravleniye Lagerej (State Administration of Camps) |

| IfZ | Institut für Zeitgeschichte, Munich (Institute for Contemporary History, Munich) |

| NKGB | Narodniy Kommisariat Gosudarstvennoy Besopasnosti (People´s Commission for State Security) |

Notes:

| [1] | Klaus Schwensen, “Zur Opferzahl des KZ Sachsenhausen (1936-1945),” unpublished. |

| [2] | Carlo Mattogno, “KL Sachsenhausen – Stärkemeldungen und “Vernichtungsaktionen” 1940 bis 1945,” in: Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung (VffG), 7. Jahrg. Vol. 2 (2003), pp. 173-185. |

| [3] | Administration [Inspektion] of the Concentration Camps, List of Number of Prisoners in all the Camps (Bestandsliste der deutschen Konzentrationslager), Status 1. Jan. and 15. Jan. 1945; in: IfZ-Archiv, Sign. Fa 183; BArch NS3/439. |

| [4] | Letter from I.P. Traynin to Molotov, GARF 7021-116-177, p. 67. Handwritten date 8. X. 45, Reg.Nr. 189. |

| [5] | Forensic Expertise on German War Crimes in Krasnodar, dated 29 June 1943 (quoted in the Trial of Kharkov). |

| [6] | Expertise of the Forensic Expert Commission, dated 15 September 1943; quoted in the Trial of Kharkov, see FN 7, pp. 12 and 77-81. |

| [7] | N.N., Deutsche Greuel in Rußland. Gerichtstag in Charkow (German Atrocities in Russia. The Trial of Kharkov) [Official Protocol of the Kharkov Trial], Stern-Verlag, Vienna undated [1945]. |

| [8] | IMT-Document USSR-54, Report of a Special Commission for the examination and investigation of the circumstances of the shooting of Polish prisoners of war in the Katyn Forest by the German fascist invaders, Smolensk, 24 January 1944. |

| [9] | Mikas Šlaža, Bestien in Menschengestalt (Beasts in Human Shape), Vilnius (Wilna), Vaga Verlag 1995. The book contains Šlaža´s complete Sachsenhausen Report in German and Lithuanian with an afterword by Domas Kaunas. |

| [10] | German list (hectography) „Russische Kriegsgefangene“ (Russian POWs), dating from 18.10. – 30.12.1941; in: GARF 7021-104-4, p. 149-150. |

| [11] | Walter Post, “Erschiessung sowjetischer Kommissare,” in: Franz W. Seidler und Alfred M. de Zayas (Ed.), Kriegsverbrechen in Europa und im Nahen Osten im 20. Jahrhundert, Verlag Mittler, Hamburg 2002, pp. 76-82. |

| [12] | There was a huge air raid shelter (Zoo-Bunker) in the area of the Berlin Zoo and close to the “Zoo” S-Bahn station. The bunker was equipped with anti-aircraft guns (Flak) and was one of the last strongholds of the defenders. |

| [13] | Soviet Prosecutor L.N. Smirnow on Tuesday, 19. Febr. 1946 (62nd day, forenoon), IMT Vol. VII, p. 635 ff. |

| [14] | N.N., REPORT ON CONCENTRATION CAMP SACHSENHAUSEN AT ORANIENBURG, [as Part 1 of a more extended report of Dutch ex-prisoners Frederik Willem Bischoff van Heemskerck and Johann Hers, translation into English by Bischoff]. Archives: Zentralnyj archive FSB RF or Rijksinstituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie, Karton 27 Sachsenhausen, Nr. 59, Mappe 3 or AS Ordner 7 (Netherlands). |

| [15] | Hellmut Bock, Bericht Konzentrationslager Sachsenhausen, presented to the Commission of the USSR to Investigate the Crimes of the German Fascists in Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp, Oranienburg, 12 June 1945. Archives: GARF, 1525-1-340, T. 3, p. 31350 – 31382 (or sheet 351-383); Copy in AS 235 M. 173 Bd. 3, Bl. 148 -181. |

| [16] | A. Sharitch, Investigation Report [to the ESC in Moscow], Berlin, 29 June 1945; in GARF 7021-104-2, p. 29 (handwritten archive number). |

| [17] | Klaus Schwensen, “The Report of the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission on the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp,” Inconvenient History, Vol. 3 No. 4 (Winter 2011). |

| [18] | Expertise of the Forensic Expert Commission, on behalf of the Investigation Group of the NKGB, [Jan. 1947]. German Translation: Staatsanwaltschaft Köln, 24 Ks 2/68 (Z), Sonderakten, Bd. 8, Bl. 1-28. Today in Hauptstaatsarchiv Düsseldorf, Bestand Gerichte, Rep. 267 Nr. 1683. |

| [19] | International Sachsenhausen Committee, official Statement, 22 April 2001. |

| [20] | Günter Morsch (Ed.) [Director of Sachsenhausen Memorial Site], Mord und Massenmord im Konzentrationslager Sachsenhausen 1936–1945 [Murder and Mass Murder in Sachsenhausen CC], Metropol-Verlag, Berlin 2005, p. 166. |

| [21] | Irene Sagel-Grande, H. H. Fuchs und C. F. Rüter, Justiz und NS-Verbrechen, University Press Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1979, Urteil 591, p. 64 – 139 ff. |

| [22] | Wolff, Georg, Kalendarium der Geschichte des KZ Sachsenhausen, Herausgegeben von der Nationale Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Sachsenhausen, Oranienburg 1987. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 4(3) (2012)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a