Auschwitz Statistics: Registrations, Occupancy, Mortality, Transfers

An Introduction

The trial of former Auschwitz camp commandant Rudolf Höss, staged in Warsaw from March 11 to 29, 1947, famously laid the foundation for the later historiography of the Auschwitz Camp: despite their inevitable biases and their obvious historical and methodical limitations, the Polish investigators nevertheless attempted to reconstruct as complete a picture as possible of events at the Auschwitz Camp. They focused on 50 aspects of camp life, each supported by numerous testimonies and a few documents. The aspects covered were:[1]

- Function of Auschwitz Concentration Camp in the political system of the government of the Third Reich.

- The creation of the camp and its expansion

- Structure of the camp

- Technical facilities of the camp

- Organization of the camp

- The system of camp authorities

- People in the camp (local significance of arrivals/deportations)

- Type of inmates, their numbering, external marking, and the treatment of the different groups

- Registration of prisoners

- Prisoners by nationality

- Soviet prisoners of war

- Women

- Children and adolescents

- Functionaries of the prisoners

- Demoralization, denunciation, prostitution

- Ways and means of preventing escapes

- Admission to the camp

- Quarantine

- Housing (water supply, latrines, delousing of blocks)

- Clothing and bedding – delousing

- Food rations

- Hunger in the camp

- Parcels and letters

- Smuggling and “organization

- Daily orders, roll calls, work, maltreatment

- Discipline and punishment, courts

- The penal company

- Suicides

- Diseases

- Organization of camp hospitals and health care

- The activities of the German doctors

- The activities of the prisoners’ doctors

- Medical experiments

- Selections/sorting and their function

- Killings in the commandos

- Shootings

- Hangings

- Injections with lethal poisons

- Gassings

- Data on the number of victims

- Looting of victims’ property

- Covering of traces and [destruction] of crematoria

- Transport to other camps

- Releases

- Underground [Resistance] organizations

- Miscellaneous

- Collective justice

- Revolts

- Criminals

- Dissolution of the camp

The accusation of the alleged gassings was, of course, in the foreground because of its importance, but this did not prevent the investigators from treating the other aspects just as thoroughly. The trial of members of the Auschwitz camp staff, staged in Krakow from November 25 to December 16, 1947, followed the same line as the Höss Trial.

The Auschwitz Museum, founded in 1947, was entrusted with historical documentation in addition to its conservational duties. In 1957, when the first issue of the journal Zeszyty Oświęcimskie appeared – and two years later in German translation under the title Hefte von Auschwitz – the museum began to shed light on the various aspects of camp life, and to analyze individual important documents. Beginning in 1958, Danuta Czech set about the arduous task of compiling the results of this research chronologically in a series of essays,[2] which were then presented in a summarized and updated form in a large book titled Das Kalendarium von Auschwitz (Czech 1989, English 1990 as Auschwitz Chronicle). In subsequent issues of the journal and in various monographs, the Auschwitz Museum staff continued their work along the line drawn by the Höss Trial, and for scholars in the field, the Kalendarium became a kind of vast thematic pool from which to draw topics for study. Whatever the verdict on the historical value of these writings – in some cases, starting with the Kalendarium, it can only be harsh (cf. Mattogno 2022) – the efforts of the Auschwitz Museum should be acknowledged for having captured camp life in Auschwitz in its entirety, something that is unfortunately unknown to most non-Polish historians.

European and American historians, despite their arrogance towards their Polish colleagues who worked for thirty years under the communist yoke, show that they are afflicted with a unique narrow-mindedness that leads them to see nothing in the Auschwitz Camp but the alleged “extermination camp.” If one reads the books of their top specialists such as Jean-Claude Pressac (1989; 1994a, especially pp. 34 and 39; 1994b) and Robert Jan van Pelt (2002), one definitely gets the impression that Auschwitz had no other function for them than that of exterminating Jews. This narrow-mindedness is in direct proportion to their ignorance of the history of the camp and its documentation, which in turn leads to blindness, as in the case of Richard Breitman, whose enigmatic interpretations of various radio transmissions intercepted and decoded by the British in connection with Auschwitz show that he believes the Auschwitz camp authorities thought of nothing else day in and day out and had nothing else to do but exterminate Jews (see Mattogno 2021, pp. 26-48).

In this part of the present study, I examine four fundamental aspects of camp life that pertain exclusively to the registered prisoners:

- The registration of prisoners admitted to the camp,

- the number of prisoners in the camp (strength or occupancy),

- the mortality among the prisoners in the camp, and

- the number of inmates transferred away from the camp toward other camps.

The first aspect was addressed by Danuta Czech in her Kalendarium, but her approach was purely chronological, so the prisoner registration numbers are given on the basis of the date on which they were assigned. However, if one wanted to know when a particular number was assigned, one would have to scour the pages of the Kalendarium and search for the appropriate transport among numerous other entries for a wide variety of events. This can be time-consuming because the numbering was not always strictly chronological; for example, registration numbers 20951-20986 were assigned on September 18, 1941, but subsequent numbers 20987-20992 were not assigned until February 11, 1942.

In the present study, therefore, I present all known number series of all known categories, male and female, in a sequential order, as will be seen in detail in the first section.

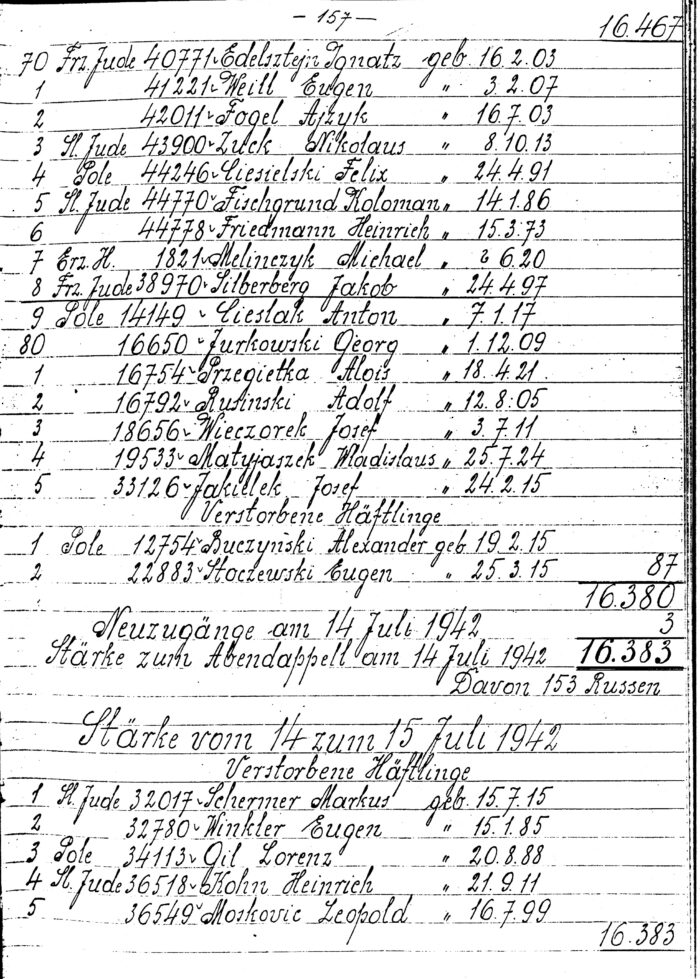

The second aspect relates to the number of prisoners present in the camp. In this case, the Kalendarium provides sketchy partial data scattered over almost 1,000 pages, derived from much more extensive documents and from communications of the Resistance movement in Auschwitz. In this regard, it is known that some of the German radio transmissions intercepted by the British during World War II and decoded by the Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park concern the Auschwitz Camp. As with other concentration camps, many of these intercepted radio transmissions report daily changes in occupancy, covering the period from January 1942 to January 1943 for the men’s camp and from September 1942 to January 1943 for the women’s camp.

In 1997, the British government turned over these decoded radio transmissions to what was then the Public Records Office in London, making them available to researchers. For the next 21 years, no orthodox Holocaust historian saw the need to analyze these documents. The reason for this is that they are seemingly abstruse columns of figures that must remain completely incomprehensible to any historian who has not studied in detail the relevant documents available, especially the Auschwitz Stärkebuch (Strength Books or Occupancy Books). The way prisoner numbers are added (new arrivals/admissions) and subtracted (departures) sometimes changes from message to message, and this is possibly the reason that has prevented even the historians of the Auschwitz Museum from dealing with these documents.[3]

In the second section, I fill this gap by placing the British decrypts in the context of documentation that is already known but has been little and unsystematically used.

The mortality of registered prisoners, i.e., prisoners who actually died and whose deaths were registered at Auschwitz, does not seem to be of much interest to Western historians, who are all obsessed with acknowledging and counting only the claimed gassing victims. Only Pressac attempted serious statistics, based largely on a summary of Auschwitz Death Books he found in Moscow, in addition to other sources. Pressac concluded that the death toll among the registered prisoners was in the order of 130,000.[4] Five years later, he corrected this figure, which is very close to that attested by documents: about 135,500.

Particularly meritorious for this research subject is the digitization of the data contained in the surviving Death Books by the Auschwitz Museum in collaboration with two German scientists, Thomas Grotum and Jan Parcer, who carried out a precise statistical analysis. The result of this work was the publication of 80,010 names of prisoners who died in Auschwitz, arranged alphabetically in two series depending on the source (Death Books or other documents), including all personal data (Staatliches Museum… 1995).

However, even the commendable essay by Grotum and Parcer has two serious shortcomings: first, it lists the number of deaths only by month and without any attempt to even understand the problem; second, it omits other important documents that enabled me to find the names of 3,452 other prisoners who died at Auschwitz and who do not appear in the Auschwitz Museum’s two lists of names. These prisoners are listed in alphabetical order in the appendix of this study. In addition, thanks to all available names, I have reconstructed a daily picture of mortality in Auschwitz from October 1941 to December 1943, as far as the sources allow.

The last part of this study titled “Transfers” was not initially part of it, but was added after the Italian and German editions had already been published. In her Auschwitz Chronicle, Czech documented that some 95,300 inmates had been transferred or evacuated away from Auschwitz Camp to other camps within the German camp system, most of them located in the west, out of reach of the advancing Red Army. However, Czech neither made that tally herself – it results by tediously counting each one of her entries mentioning such a transfer – nor is it even close to being complete. In fact, as I document in this last part of my study, the real figure is about three times as high.

This last part of the present study is of enormous import. Mainstream historians will certainly keep claiming that the documented list of mortalities presented here is woefully inaccurate because it does not include the hundreds of thousands of unregistered, hence undocumented wanton mass killings that the orthodoxy insists happened in the alleged homicidal gas chambers. To ultimately and completely refute them on this point, they ask us to prove a negative: that there were no such gassings. My massive body of research results on the alleged homicidal gas chambers at Auschwitz is as close as anyone might ever get to such a negative proof. But that’s not good enough for the orthodoxy either. They just keep on claiming, pointing to equally merely claiming “witnesses.”

However, they cannot refute the positive proof that the German authorities, with the war drawing to an end, made sure with lots of efforts that almost three hundred thousand witnesses to their deeds survived by evacuating them. They thus actively assisted in the creation of a witness body so immense in numbers that it would have been illusory to assume that anything which happened at Auschwitz could have remained a secret. The fact that they did not only not kill these people, but helped them survive so they can tell their stories later, is positive proof that the German authorities where under the firm impression that they had nothing to hide, and that these 300,000 witnesses posed no threat to them whatsoever.

The four parts of this study are full of tables that clearly summarize the data on registrations, camp occupancy, mortality and transfers. The result is an easy-to-read reference work that is useful and even indispensable for Auschwitz researchers.

* * *

Print and eBook versions of the complete book are available from Armreg at armreg.co.uk.

Endnotes

| [1] | AGK, NTN, 174, pp. 13-38. |

| [2] | The general title of this series of essays is “Kalendarz wydarzeń w obozie koncentracyjnym Oświęcim-Brzezinka”; they appeared divided by years as follows in the Museum’s journal Zeszyty Oświęcimskie: 1940-41: No. 2/1958; 1942: No. 3/1958; 1943: No. 4/1960; 1944 (until June 30), No. 6/1962; 1 July 1944 to 27 January 1945: No. 7, 1963. German translation: “Kalendarium der Ereignisse im Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau,” in Hefte von Auschwitz: 1940-1941: No. 2 (1959), pp. 89-118; 1942: No. 3 (1960), pp. 47-110; first half 1943: No. 4 (1961), pp. 63-111; second half 1943: No. 6 (1962), pp. 43-87; first half 1944: No. 7 (1964), pp. 71-103; July 1944 to January 1945: No. 8 (1964), pp. 47-109. |

| [3] | In contrast, the historians of the Majdanek Museum have already evaluated the data from the corresponding decrypts. See Kranz et al. |

| [4] | Pressac 1989, pp. 144-146; in his 1994 book, he reduced that figure after a few corrections to 126,000 (1994b, pp. 192-195). |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2023, Vol. 15, No. 1; taken, with generous permission from Castle Hill Publishers, from Part 2 of Carlo Mattogno, The Real Auschwitz Chronicle, titled "The History of the Auschwitz Camps Told by Authentic Wartime Documents (Castle Hill Publishers," Uckfield, February 2023

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: