Clergy Imprisoned in Dachau during and after World War II

Dachau was used partially as a detainment facility for Christian clergy in Europe. There were more than 1,000 clergymen in Dachau in 1940, which was about 4% of the inmates in Dachau that year. After 1940, all priests imprisoned by Germany were relocated to Dachau, with a total of 2,762 clergymen imprisoned in Dachau by the end of the war. Catholics made up 2,579 of this total, while the rest were mostly Protestant ministers.[1]

The largest national contingent was from Poland (1,780, or 64%), with the Germans (447, or 16%) and other nationalities following far behind. The clergymen were housed in Barracks Nos. 26, 28 and 30 in the northwest corner of the camp. They were initially allowed to convert one room of Barracks 26 into a chapel, but after 1941 the Polish priests in Barracks 28 were barred from using this chapel.[2]

Medical Experimentation

Dachau was used as a center for medical experimentation on humans involving malaria, high altitudes, freezing, phlegmon and other experiments. This has been corroborated by hundreds of documents and by witnesses in the Doctors’ Trial at Nuremberg, which opened on December 9, 1946, and ended on July 19, 1947.[3]

The malaria experimentation at Dachau was performed by Dr. Klaus Karl Schilling, who was an internationally famous parasitologist. Dr. Schilling was ordered by Heinrich Himmler in 1936 to conduct medical research at Dachau for the purpose of specifically immunizing individuals against malaria. The medical supervisor at Dachau would select the people to be inoculated and then send this list of people to Berlin to be approved by a higher authority. Those who were chosen were then turned over to Dr. Schilling to conduct the medical experimentation.[4]

A total of 176 Polish priests, four Czech and five German clergymen were subjected to malaria experimentation at Dachau. Two priests died as a result of these malaria experiments: Father Josef Horky from Czechoslovakia, and Father Francis Dachtera from Poland. It is also possible that other clergymen died from indirect pathologies such as tuberculosis or renal failure induced by these malaria experiments.[5]

Phlegmons were induced in inmates at Dachau by intravenous and intramuscular injection of pus. Various natural, allopathic and biochemical remedies were then used to attempt to cure the resulting infections. The phlegmon experiments were conducted by National Socialist Germany to find an antibiotic similar to penicillin for the infection.[6] A total of 40 clergymen in Dachau were subject to phlegmon experiments. Eleven out of this group died, and many of the survivors suffered adverse health effects from these experiments.[7]

Another Catholic priest who had survived malaria experimentation, Father Leo Michalowski, was selected to undergo tests of his resistance to immersion in ice water. Although Michalowski survived this experiment, it left him with a weak heart for the rest of his life.[8]

Typhus

The first typhus epidemic at Dachau began in December 1942. Quarantine measures were taken to prevent its spread. The end of this typhus epidemic was declared on March 14, 1943, with the disease killing between 100 and 250 inmates in the camp.[9]

The second typhus epidemic struck Dachau in December 1944 and was much more widespread. This outbreak of endemic typhus caused the 15 blocks in the eastern part of the camp to be isolated from the rest of the camp. Many of the priests in Dachau volunteered to alleviate the sufferings of these sick Dachau inmates. These volunteer priests were all contaminated by typhus, and most of them died as a result.[10]

Typhus was the primary reason for the huge piles of dead bodies at Dachau when U.S. troops entered the camp. Dr. Charles P. Larson, an American forensic pathologist, was at Dachau and conducted hundreds of autopsies at Dachau and some of its sub-camps. Dr. Larson stated in regard to these autopsies:[11]

“Many of them died from typhus. Dachau’s crematoriums couldn’t keep up with the burning of the bodies. They did not have enough oil to keep the incinerators going. I found that a number of the victims had also died from tuberculosis. All of them were malnourished. The medical facilities were most inadequate. There was no sanitation […].”

Dr. John E. Gordon, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of preventive medicine and epidemiology at the Harvard University School of Public Health, was with U.S. forces at the end of World War II. Dr. Gordon determined that disease, and especially typhus, was the Number One cause of death in the German camps. Dr. Gordon explained the causes for the outbreaks of disease and typhus:[12]

“Germany in the spring months of April and May [1945] was an astounding sight, a mixture of humanity traveling this way and that, homeless, often hungry and carrying typhus with them. […]

Germany was in chaos. The destruction of whole cities and the path left by advancing armies produced a disruption of living conditions contributing to the spread of disease. Sanitation was low grade, public utilities were seriously disrupted, food supply and food distribution was poor, housing was inadequate and order and discipline were everywhere lacking. Still more important, a shifting of population was occurring such as few times have experienced.”

Famine

The food rations received by inmates in German concentration camps decreased in May 1942 due to shortages caused by the devastated German war economy. These shortages became a famine, which reached its nadir in midsummer 1942. The weights of the clergymen in Dachau dropped substantially due to the inadequate food supply.[13] The death rate in Dachau rose substantially, and the clergy did not escape this general misery.[14]

Conditions began to improve in Dachau when Martin Weiss became camp commandant in August 1942. Paul Berben wrote:[15]

“From November [1942] food parcels could be sent to clergy and the food situation improved noticeably. Germans and Poles particularly received them in considerable quantities from their families, their parishioners and members of religious communities. In Block 26 100 [parcels] sometimes arrived on the same day. This all bore witness to the continuing feeling of Christian fellowship which survived all persecution. […]

This period of relative plenty lasted till the end of 1944 when the disruption of communications stopped the dispatch of parcels. Nevertheless, the German clergy continued to receive food through the Dean of Dachau, Herr Pfanzelt, to whom the correspondents sent food tickets.”

As the Allies closed in on the center of Germany toward the end of the war, large numbers of prisoners were evacuated from camps near the front and moved to the interior. Dachau, being centrally located, was a key destination for these transfers. So while food became more difficult to obtain, the need for food increased with the transfer of prisoners to Dachau from other camps. This resulted in major food shortages at Dachau and a major increase in deaths in the camp near the end of the war.[16]

Polish Priest Deaths

The book The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945 by Guillaume Zeller states that National Socialist Germany was intent on killing the Polish elite.[17] Zeller claims that 868 out of 1,780 Polish priests died during their internment in Dachau. This death rate of over 48% of the Polish priests in Dachau is supported by a book written by Johann Neuhäusler, who was interned in Dachau from July 1941 to April 1945.[18]

Neuhäusler’s book contains a table indicating that 868 out of 1,780 Polish priests and 166 out of 940 non-Polish clergymen died in Dachau. However, Neuhäusler did not reference where he obtained the figures in his table. Moreover, as a “special prisoner” separated from the general camp, Neuhäusler wrote that he could not learn all that happened in Dachau. Neuhäusler’s statistics did not originate from his personal experience in Dachau.[19]

Jewish historian Harold Marcuse writes about the survival rate of priests in Dachau:[20]

“The 2,579 Catholic clergymen imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp had been a special group among the camp inmates. We recall that in 1940 all of the Christian clergymen being held in ‘protective custody’ in the Reich—about 1,000 at that time—were consolidated in Dachau. […] About 450 of the final number were German or Austrian (the Poles with 1,780 were the largest national group), and they had a relatively high survival rate.”

In his book Dachau, 1933-1945: The Official History, Paul Berben used Neuhäusler’s table indicating that 868 out of 1,780 Polish priests in Dachau died.[21] Berben wrote that some 500 Polish clergy, most of them elderly, arrived in Dachau by train in deplorable condition on October 29, 1941. Berben said these clergymen were not issued adequate winter clothes, and that only 82 survived their internment in Dachau.[22] Zeller writes that more than 300 of these mostly elderly disabled Polish clergymen were sent to the carbon-monoxide gas chamber at Hartheim Castle in Austria.[23]

Berben also wrote that 304 members of the Polish clergy were exterminated in various ways, including “liquidated inside the camp, in the showers or in the Bunker.”[24] Berben did not explain how Polish priests could have been exterminated in the showers at Dachau. Historians and former Dachau inmates generally agree that there were no functioning gas chambers inside Dachau.[25] Berben in his own book even stated that “the Dachau gas-chamber was never operated.”[26]

Dachau Clergy Mistreated after Liberation

The Americans who took over Dachau were intent on exploiting Dachau for propaganda purposes. Photographers repeatedly visited Dachau to take pictures and film newsreel footage of the dead. Some clergymen petitioned American authorities to improve their lot. For example, Father Michel Riquet protested in a letter to Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, commander-in-chief of the Allied forces:[27]

“You will understand our impatience and even our astonishment at the fact that, more than 10 days after greeting our liberators, the 34,000 detainees of Dachau are still prisoners of the same barbed-wire fences, guarded by sentinels whose orders are still to fire on anyone who attempts to escape—which for every prisoner is a natural right, especially when he is told that he is free and victorious. In the barracks that are visited every day by the international press, some men continue to stagnate, stacked in these triple-decker beds that dysentery turns into a filthy cesspool, while the lanes between the blocks continue to be lined with cadavers—135 per day—just like in the darker times of the tyranny that you conquered.“

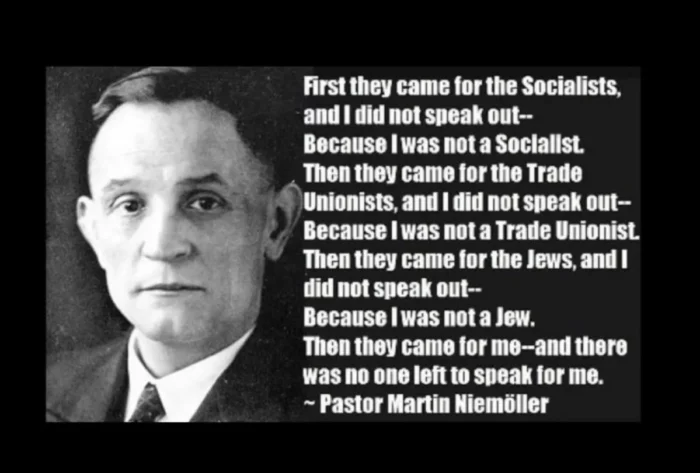

The German clergymen who left Dachau also discovered that Germans were facing severe deprivations and starvation after the war. German Protestant Church president and former Dachau prisoner Martin Niemöller said to an American audience when he toured the United States from December 1946 to April 1947:

“The offices of our [American] military government are very nicely and cozily heated and our military government people live a good life as far as nourishment and everything else, even housing, is concerned. But they don’t know how people really think and react who are hungry, who are on the way to starving.”

Niemöller claimed that Germans were receiving no better than “the lowest ration ever heard of in a Nazi concentration camp.”[28]

Although Niemöller raised more money than expected from his American tour, he was disappointed in its outcome because he was not able to improve U.S. occupation policies in Germany. After months in America, Niemöller’s return to war-ravaged Germany came as a shock. Niemöller wrote to Pastor Ewart Turner:[29]

“The winter is over, but you feel it everywhere—in the cold which is still harboring in the rooms, especially in this old castle with its thick stone walls. The water pipes are broken. No running water in kitchen or toilet. Sitting at my desk I shiver from cold even now, and the only place where I feel some relief is once again in the bed. The food situation is more than difficult, and I scarcely dare to take a slice of bread, thinking that Hertha, Tini, and Hermann [his children] are far more in need of having it than I, and I can’t help feeling guilty for being so well fed [in the United States]. The whole aspect of life is grim and dark; you see the traces of progressive starvation in every face you come to see.“

The physical and emotional toll of hunger, cold and disillusionment made life in Germany intolerable for Niemöller. Niemöller’s wife Else bemoaned when they got back to Germany from America, “It was so much easier there than here.” Niemöller told Pastor Turner that if things didn’t improve, “I should prefer to be back in my cell number 31 at Dachau.” Niemöller blamed “the followers of the Morgenthau Plan” who had moved their “headquarters from Washington to the American Zone.”[30]

In another letter to Turner in the fall of 1947, Niemöller wrote:

“The [coming] winter will be a very severe test for all of us. The rations in fat and meat have been cut again to 25 grams of butter and 100 grams of meat a week! And no potatoes. The normal consumer probably will die this winter, and that Jew [in the occupation forces] will have been right who answered my question, what would become of the too many people in the Western Zones, by saying: ‘Don’t worry, we shall look after that and the problem will be solved in quite a natural way!'”

Niemöller understood the Jewish official’s phrase “a natural way” to mean death by starvation.[31]

First they came for the Holocaust Revisionist, and I did not speak out – because I was not a Holocaust Revisionist.

Then they came for the National Socialist, and I did not speak out – because I was not a National Socialist.

Then they came for the Nationalist, and I did not speak out – because I was not a Nationalist.

Then they came for me – and there was no one left to speak out for me.

Almost 150 German and Austrian priests were released from Dachau between March 27 and April 11, 1945. Among the liberated priests were several well-known individuals, including the chaplain Georg Schelling; Father Otto Pies, Pallotine Father Josef Kentenich, founder of the Schoenstatt Movement; and Father Corbinian Hofmeister, Abbot of the Benedictine Abbey in Metten, who was detained in the bunker of honor. These priests did not have to wait for the Americans to take over the camp.[32]

Positive Aspects of Dachau Internment

Many clergymen in Dachau came to view their imprisonment in Dachau as a positive experience. Father Leo de Coninck summarized his stay in Dachau:

“Three years of experiences that I would not have missed for anything in the world.”

While Father de Coninck’s statement may be surprising, his statement recurs in the testimonies of many clergymen imprisoned in Dachau.[33]

Martin Niemöller, for example, had some favorable memories of Dachau. On his speaking tour in America, Niemöller recalled sharing quarters with three Catholic priests in Dachau and praying together “according to the Roman customs every morning, every noontime, and every night.” Niemöller said:

“We became brethren in Christ not only by praying together but by common listening to the Word of God.”

Without fail, Niemöller told and retold the story of his international and multi-denominational congregation on Christmas Eve 1944 in Dachau.[34]

Catholic Bishop Johannes Neuhäusler also preferred not to think about his bad experiences in Dachau. Neuhäusler said, “I prefer to speak about the nice memories associated with the name Dachau,” such as the ecumenical Bible readings in the camp, and the Christmas tree the SS set up for prisoners in 1941.[35]

Father Maurus Münch said:

“Dachau was, in the designs of Providence, the cradle of ecumenism lived out completely. Never in the history of the people of God had there been so many secular and religious priests of all Christian confessions, [who were] united in a community of life and suffering, as during the great witness of Dachau.”

While Catholic priests made up the vast majority of clergymen in Dachau, they established friendly and fraternal relations with Protestant pastors and clergymen of other faiths.[36]

Dachau became a laboratory for ecumenical dialogue. Father Münch wrote:[37]

“In Dachau, we were united fraternally in the breath of the Holy Spirit, strengthened in Christ to serve Him behind the watchtowers, the electrified fences and the barbed wire. We sought unity in our discussions and our dialogues. […] In authentic fraternity and common prayer, we laid the foundations for new relations between the different churches. […] The priests in Dachau and the Christian laymen took home with them, to their churches and their families, the lived experience of unity.“

Endnotes

| [1] | Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 43-44, 222. |

| [2] | Ibid., p. 44. |

| [3] | Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945: The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 123. |

| [4] | McCallum, John Dennis, Crime Doctor, Mercer Island, Wash.: The Writing Works, Inc., 1978, pp. 64-65. |

| [5] | Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, Cal.: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp. 152-154. |

| [6] | Pasternak, Alfred, Inhuman Research: Medical Experiments in German Concentration Camps, Budapest, Hungary: Akadémiai Kiadó, 2006, p. 149. |

| [7] | Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, Cal.: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp. 157-158. |

| [8] | Ibid., p. 158. |

| [9] | Ibid., pp. 124-125. |

| [10] | Ibid., pp. 126-132; Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 232. |

| [11] | McCallum, John Dennis, Crime Doctor, Mercer Island, Wash.: The Writing Works, Inc., 1978, pp. 60-61. |

| [12] | Gordon, John E., “Louse-Borne Typhus Fever in the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army, 1945,” in Moulton, Forest Ray, (ed.), Rickettsial Diseases of Man, Washington, D.C.: American Academy for the Advancement of Science, 1948, pp. 16-27. Quoted in Berg, Friedrich P., “Typhus and the Jews,” The Journal of Historical Review, Winter 1988-89, pp. 444-447, and in Butz, Arthur Robert, The Hoax of the Twentieth Century, Newport Beach, Cal.: Institute for Historical Review, 1993, pp. 46-47. |

| [13] | Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, Cal.: Ignatius Press, 2017, p. 107. |

| [14] | Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945: The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 150. |

| [15] | Ibid., p. 151. |

| [16] | Cobden, John, Dachau: Reality and Myth in History, Costa Mesa, Cal.: Institute for Historical Review, 1991, pp. 21-23. |

| [17] | Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, Cal.: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp. 11, 27. |

| [18] | Ibid., pp. 18, 258. |

| [19] | Neuhäusler, Johannes, What Was It Like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?, Dachau: Trustees for the Monument of Atonement in the Concentration Camp at Dachau, 1973, pp. 3, 25-26. |

| [20] | Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 221. |

| [21] | Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945: The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 277. |

| [22] | Ibid., p. 148. |

| [23] | Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, Cal.: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp. 162-165. |

| [24] | Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945: The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, pp. 148-149. |

| [25] | For example, Neuhäusler, Johannes, What Was It Like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?, Dachau: Trustees for the Monument of Atonement in the Concentration Camp at Dachau, 1973, pp. 15, 29. |

| [26] | Berben, Paul, Dachau, 1933-1945: The Official History, London: The Norfolk Press, 1975, p. 8. |

| [27] | Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, Cal.: Ignatius Press, 2017, p. 212. |

| [28] | Hockenos, Matthew D., Then They Came For Me: Martin Niemöller, The Pastor Who Defied the Nazis, New York: Basic Books, 2018, p. 204. |

| [29] | Ibid., p. 212. |

| [30] | Ibid. |

| [31] | Ibid., p. 213. |

| [32] | Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, Cal.: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp. 204-205. |

| [33] | Ibid., p. 217. |

| [34] | Hockenos, Matthew D., Then They Came For Me: Martin Niemöller, The Pastor Who Defied the Nazis, New York: Basic Books, 2018, p. 203. |

| [35] | Marcuse, Harold, Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 229. |

| [36] | Zeller, Guillaume, The Priest Barracks: Dachau, 1938-1945, San Francisco, Cal.: Ignatius Press, 2017, pp. 222-223. |

| [37] | Ibid., pp. 223-224. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2019, Vol. 11, No. 3

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a