Evidence for the Presence of “Gassed” Jews in the Occupied Eastern Territories, Part 2

The following article is a continuation of Thomas Kues’s “Evidence for the Presence of ‘Gassed’ Jews in the Occupied Eastern Territories, Part 1.” Thomas Kues’s analysis takes up the revisionist proposal that Jews sent to the “extermination camps” and allegedly gassed there were in fact deloused and then sent away, the vast majority of them to the occupied eastern territories. The camps therefore actually functioned as transit camps. The transit camp hypothesis is in perfect harmony with documented National Socialist Jewish policy as expressed in official and internal reports, documents on the Jewish transports, and even in classified communications between leading SS members.

3. A Survey of the Testimonial Evidence

3.3.10. Lev Saevich Lansky and Isak Grünberg

Lev Saevich Lansky, who had been an inmate of the Maly Trostinec camp from 17 January 1942 onward, was interrogated by a Soviet investigative commission on 9 August 1944. Concerning the Jews deported from Altreich, Austria and the Protectorate to Maly Trostinec[1] (which is located 12 km southeast of Minsk),[2] Lansky made the following statement:[3]

“We all got soap and clothing from German Jews who had been slaughtered. There were ninety-nine transports of a thousand people each that came from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia.”

When asked about the fate of these deportees, Lansky answered that they were “all shot”.[4]

It is generally agreed that five transports from Theresienstadt (Da220, Da222, Da224, Da226, Da228) reached Maly Trostinec between July and September 1942, and that each of them carried 1,000 deportees.[5]

Holocaust Historian Gertrude Schneider asserts that, except for a first transport departing on 28 November 1941, all transports from Vienna to the General District of Weißruthenien (White Ruthenia) “ended up at the killing grounds of Maly Trostinec”,[6] despite the fact that said transports are listed in documents as bound for nearby Minsk. On the other hand Schneider also states that the transport departing Vienna on 6 May 1942 “arrived May 11 at the Minsk railroad station”, whereupon 81 Austrian Jewish deportees were “selected for work on the farm at Maly Trostinec”.[7] Schneider also mentions a survivor from the transport departing Vienna on 27 May 1942 (Da-204), Marie Mack, who was later deported from the Minsk Ghetto to Lublin in September 1943;[8] as well as the arrival of the 7 October 1942 transport (Da-230) at the Minsk railway station.[9] Thus of the 25 transports departing Vienna for Minsk in 1942, only 22 or 23 could have been diverted to Maly Trostinec. If Lansky’s statement about the number of transports from the west to Maly Trostinec is correct (or more or less correct as to order of magnitude), where did the other 71 or 72 transports come from? Did further, indirect transports reach Maly Trostinec via the “extermination camps”?

German exterminationist historian Christian Gerlach writes that 18 Jewish transports from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia to Minsk and the rest of Generalbezirk Weißruthenien were originally planned for the period 10 November – 16 December 1941, and a further 7 transports between 10 and 20 January 1942. In the end, however, due to the protests of Generalkommissar Kube, only a total of 7 transports were sent to Minsk in November and December, while all the January transports were cancelled. To compensate for the decreased number of transports, more convoys to Riga were added.[10] The deportations were then commenced anew following the visits of Eichmann, Himmler and Heydrich to Belarus in March and April 1942.

Gerlach provides a list of 18 transports to Weißruthenien that are “certain to have arrived” and 5 “uncertain” ones.[11] In the more comprehensive list provided by Graf and Mattogno there are a total 34 transports for the period in question (May-November 1942). Three of the “uncertain” transports in Gerlach’s list are not included in the latter: one from Theresienstadt departing on 13 June 1942 with some 1,000 deportees, one transport from Dachau which arrived sometime in June 1942 (attested to by a surviving deportee, Ernst S.), and one from an unknown origin arriving in the first half of August 1942 (attested to by an activity report of the “Gruppe Arlt” from 25 September 1942). The “uncertain” transport listed by Gerlach as departing from Theresienstadt on 20 August 1942 with some 1,000 deportees is concluded by Graf and Mattogno to have been sent to Riga; Gerlach himself notes that “this transport, billed for Minsk, was possibly redirected.”[12] A further “uncertain” Theresienstadt transport (“Be”) departing on 1 September 1942 with some 1,000 deportees was in fact sent to Raasiku in Estonia, as confirmed by numerous eyewitnesses.[13]

As for the Theresienstadt transport departing on 13 June 1942, the Terezin Studies website[14] lists a transport designated “AAi” as departing for an “unknown” destination on this date. The Dachau transport in June 1942 is yet more mysterious. We may recall here that the Swedish-Jewish periodical Judisk Krönika in its issue from October 1942 reported that Jews from Dachau and other German concentration camps had been deported to Pinsk for drainage work (cf. §3.1.3. above). Mainstream historiography knows of no transports of Jews from Dachau to the occupied eastern territories. It is documented that there were transports from Dachau to two of the “extermination camps”, namely Auschwitz and Majdanek. The number of these deportees amounted to 4,767 and 2,933 respectively. However, Danuta Czech lists no transports as arriving to Auschwitz from Dachau during June 1942, and the only known transports from Dachau to Majdanek took place in January and February 1944.[15] The purported Dachau transport to Belarus remains an enigma.

It is when we take a look at transports departing from the Theresienstadt (Terezin) ghetto in October 1942 that things get really interesting. In 1993 the German historian Hans Safrian wrote:

“In the summer of 1942 Minsk and Maly Trostinec became the end station for deportation transports from Central Europe, mainly from Terezin and Vienna. […] The destination of five further deportation transports from Terezin in October 1942 has not yet been clarified. […] In the circulation plan for October the station of Izbica [in the General Government] was designated as destination for the transports from Terezin, which suggests that these people were murdered in one of the ‘Aktion Reinhard’ death camps. Nonetheless there is evidence indicating that in October 1942 five trains from Theresienstadt were conducted to Minsk / Maly Trostinec.”[16]

The “evidence” indicating that the five Theresienstadt transports Bt, Bu, Bv, Bw and Bx arrived in Maly Trostinec consists of a reference to H.G. Adler’s study Der verwaltete Mensch from 1974. In a previous study on the Theresienstadt Ghetto from 1955 Adler had concluded that the same transports were sent to Treblinka,[17] but by 1974 he had changed his mind on the issue:[18]

“On 8 August 1942 a certain Dr. Engineer Jacobi of the General Management Office East [Generalbetriebsleitung Ost] of the German Reich Railway [Deutsche Reichsbahn] wrote to inform the Main Railway Offices in Minsk and Riga, the Reich Railway Head Office, the General Office of the Eastern Railways [Ostbahn] in Cracow and also the General Management Offices in Essen and Munich about the ‘Special trains [Sonderzüge] for resettlers, harvest workers and Jews in the period from 8 August to 30 October 1942′. To the cover letter was attached, among other things, a ‘circulation plan’ [Umlaufplan], which was later partially revised. The following trains, which were supposed to carry each 1,000 people, were assigned for the deportation of Jews (the declared destination Wolkowysk indicates Minsk): […]

21.9. [1942] from Theresienstadt to Wolkowysk

23.9. from Nuremberg to Theresienstadt

24.9. from Vienna to Theresienstadt

26.9. from Berlin to Riga

27.9. from Darmstadt to Theresienstadt

28.9. from Vienna to Wolkowysk

1.10. from Vienna to Izbica

3.10. from Berlin to Riga

from Berlin to Theresienstadt

5.10. from Vienna to Wolkowysk

from Theresienstadt to Izbica

6.10. from Darmstadt to Theresienstadt

8.10. from Theresienstadt to Izbica

9.10. from Vienna to Theresienstadt

12.10. from Theresienstadt to Izbica

15.10. from Theresienstadt to Izbica

19.10. from Theresienstadt to Izbica

22.10. from Theresienstadt to Izbica

26.10. from Theresienstadt to Izbica

29.10. from Theresienstadt to IzbicaIn this contemporary schedule […] there are some aspects worthy of note. First of all Auschwitz was at this time still not intended as a destination for transports from the Reich proper. […] Following the series of transports to Wolkowysk the destination of the transports departing Theresienstadt is given as Izbica from the beginning of October onward. In reality none of the deportees reached the ghettos in Izbica or in its vicinity, if not only as transit camps from where they were sent to the nearby extermination sites Belzec, Sobibor and Majdanek. The destination Izbica thus refer to these sites. However, all of the transports from Theresienstadt during October 1942, with the exception of the last one on the 26th (from the 29th no more departed) with which began the series of convoys to Auschwitz, were in fact directed to the vicinity of Minsk and the extermination camp Trostinetz which is here implied with the station Wolkowysk.”

Czech Holocaust historian Miroslav Karny has made the following comment on Adler’s later hypothesis:[19]

“In his newer work he [Adler] asserts that the October transports departing from Theresienstadt did instead arrive via Izbica at the extermination camp in Trostinez, ‘which is here implied with the station Wolkowysk.’ In no document relating to any of the October transports from Theresienstadt is Wolkowysk mentioned as a station where the ‘travellers’ would have to reembark on a freight train and continue their journey to Minsk or Koloditschi.”

It is indeed true that Adler does not provide reference to a document stating that the October transports were routed to Wolkowysk (which is an important railway junction in western Belarus). What then prompted Adler to change his mind? As we will see below it was likely the testimony of a certain former Trostinec detainee.

Karny, like other mainstream historians, asserts that the Jews on the five transports Bt-Bx departing from Theresienstadt in October 1942 were killed in Treblinka. It is in fact clear that at least one of the five trains—the second transport departing on 8 October (Bu)—reached Treblinka, as one of the Jews on board, Richard Glazar, was picked out to work in the camp and later survived the Treblinka prisoner revolt to became a Holocaust witness.[20] Reportedly only a few dozen of the in total 8,000 Theresienstadt deportees were selected for work in Treblinka as Glazar was, while the rest were “gassed”.[21]

Ironically, while criticizing Adler for not backing up his assertion, Holocaust historians like Karny are completely unable to provide any documentary proof of the alleged homicidal gas chambers in which these deportees were supposedly killed. The only one of their conclusions which is acceptable is thus that these five trains were sent to Treblinka—but from this does not follow that the Jews in the convoys were killed there.

What kind of transports arrived at the station of Maly Trostinec? In an account based mainly on West German court material, Paul Kohl has the following to say about this alleged extermination site:[22]

“In the summer of 1942 a railway station was built by a one-way track near the collection point in the part of the camp closest to the [Minsk-Mogilev] road (the railway line had previously ended at Michanowice). The trains with Jews from the Reich, which had previously stopped at the Minsk freight yard, were now immediately redirected from there to Trostenez. Twice a week trains arrived from the Reich, from Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, France. They arrived on Tuesdays and Fridays and – in order to avoid commotion – always in the early morning between four and five o’clock. Also from the Dachau Concentration Camp a train arrived in June 1942.”

In 1974 H.G. Adler described the Trostinec camp thus:[23]

“In a small village, which before the occupation had constituted a kolkhoz, the camp [Trostinec] was located; to this belonged an estate of 250 hectares. Here the prisoners were also housed, first in pig sties, later in barracks which each housed 150 to 160 people. During 1942 a total of 39,000 Jews from Germany, Austria, Bohemia-Moravia, Luxembourg, Holland and also from the Soviet Union were brought to Trostinetz, but in the camp itself there were never more than 640 Jews at one time, most of them Jews from Vienna; among the inmates there were also some hundreds of Russian prisoners of war.”

Needless to say the dogma of mainstream historiography does not allow for transports of Jews from Poland, Holland, France or Luxembourg to Belarus.

If one or more trains arrived at the station “twice a week”, as Kohl writes, this would mean that at least 50 convoys arrived at Trostinec during the second half of 1942. According to Gerlach, from 10 August 1942 on, all the Jewish deportation trains were redirected from Minsk to Trostinec via the Kolodischtschi station (15 km east of Minsk).[24] Yet if we look at the listed transports from 11 August to 28 November, we find that it contrasts with Kohl’s description of the arrivals at Minsk/Maly Trostinec:

| Date of Departure | Origin | Deportees | Interval (days) |

| 11 Aug (Tue) | Vienna | 1,000 | |

| 17 Aug (Mon) | Vienna | 1,003 | 6 |

| 18 Aug (Tue) | Vienna | 1,000 | 1 |

| 25 Aug (Tue) | Vienna | 1,000 | 7 |

| 25 Aug (Tue) | Theresienstadt | 1,000 | 0 |

| 31 Aug (Mon) | Vienna | 967 | 6 |

| 1 Sept (Tue) | Vienna | 1,000 | 1 |

| 8 Sept (Tue) | Theresienstadt | 1,000 | 7 |

| 14 Sept (Mon) | Vienna | 992 | 6 |

| 22 Sept (Tue) | Theresienstadt | 1,000 | 8 |

| 30 Sept (Wed) | Vienna | 1,000 | 8 |

| 7 Oct (Wed) | Vienna | 1,000 | 7 |

| 18 Nov (Sun) | Hamburg | 908 | 11 |

| 28 Nov (Wed) | Vienna | 999 | 10 |

We see here that the direct transports to Belarus during the period in question departed in general 6-8 days apart, and until 30 September always on Mondays or Tuesdays. From the memoirs of Karl Loewenstein we know that it took 4 days for a transport from Berlin to reach Minsk.[25] The trip from Vienna, Hamburg or Theresienstadt would probably not have taken much less or longer. Accordingly most of the transports would likely have reached Maly Trostinec on either a Thursday or a Friday (on a Saturday for three of the last four transports). How then could there also arrive transports weekly on Tuesdays, unless one allows for indirect transports arriving from the “extermination camps”? This, however, is exactly what is claimed by the Maly Trostinec eyewitness brought forward by Adler in his 1974 study: the Austrian Jew Isak Grünberg (b. 1891).

Grünberg was deported from Vienna on 5 October 1942 (according to him; preserved railway documents give the departure date as 7 October) and on 9 or 10 October 1942 reached Maly Trostinec, where Grünberg himself, his wife and their three children were selected for work in the camp. At their arrival, there were “already a lot of Jews” in the camp, “mainly from Poland”.[26] By this point in time there were, according to mainstream historiography, to follow only two more transports from the west to Belarus—one convoy departing from Hamburg on 18 November 1942 and another one departing Vienna on 28 November 1942—but according to Grünberg several transports from the west reached Trostinec in the months following his arrival:

“According to my estimate there were 1200 to 1300 Jews in the camp. This figure remained unchanged, the fresh supply [of manpower] was taken from camps, from Theresienstadt and Auschwitz and probably also from other ones. […] Transport after transport arrived. Often we never even heard where they came from, since it frequently happened that all [of the deportees] were immediately liquidated.”[27]

Further on in his testimony Grünberg estimates the number of Jews allegedly liquidated near Trostinec to “certainly 45,000 people at the least”.[28] It is not made clear in the testimony whether this estimate refers to merely Grünberg’s own period of stay at Trostinec or the whole operational period of the camp.

The mention of Auschwitz is crucial: here we have a witness who explicitly states, based on his own experience, that transports arrived in the occupied eastern territories from one of the “extermination camps”. The mention of Theresienstadt is likewise of utmost importance: The last documented transport from Theresienstadt to Belarus departed on 22 September 1942, i.e. more than two weeks before Grünberg arrived in Trostinec. In October 1942, as has already been mentioned, five transports were sent from Theresienstadt to Treblinka:

| Deportation date | Designation | Number of Deportees |

| 5 October | Bt | 1,000 |

| 8 October | Bu | 1,000 |

| 15 October | Bv | 1,998 |

| 19 October | Bw | 1,984 |

| 22 October | Bx | 2,018 |

From 26 October 1942 onward the Theresienstadt transports were sent to Auschwitz.[29]

The transports from Theresienstadt which Grünberg states arrived at Trostenic following his own arrival at the camp on 9 or 10 October must therefore have arrived either via Auschwitz or Treblinka. Since Grünberg explicitly mentions Auschwitz together with Theresienstadt as origins of the transports it seems most likely that they reached Belarus via Treblinka. Possibly these deportees simply did not recall the name of this transit camp in the middle of nowhere, where they might have stayed only a few hours.

Unfortunately Grünberg does not state the nationality of the arrivals, although it is presumable that the Theresienstadt Jews were (for the most part) Czech. His statement that most of the Jews in the camp at the time of his arrival were Polish implies one or more undocumented Jewish transports from Poland. That transports of Polish Jews reached Trostinec is also maintained by Belarussian Holocaust historian Marat Botvinnik.[30] From where Kohl and Adler derive their assertions that also Jews from Luxembourg, Holland, France were sent to Trostinec is unclear. In Kohl’s case it is possibly unpublished court material, in Adler’s it is more likely other testimonial sources. Grünberg in his testimony mentions two Trostinec survivors who had returned to Austria: Julie Sebek and Siegmund Prinz.[31]

3.3.11. Yudi Farber, K. Sakowicz and Aba Gefen

Yudi Farber, a Russian-Jewish engineer, left an account in the early post-war years of how he was sent on 29 January 1944 to Ponary (also spelt Ponar, in Lithuanian Paneriai), an alleged extermination site north of Vilna, from where he managed to escape on 15 April 1944. In this we find the following passage describing his arrival at Ponary:[32]

“We went under a canopy; there was a wooden structure that they referred to as a bunker, with a small kitchen. The women said that Jews from Vilnius and surrounding areas were living here. They were hiding in the ghetto but were found, sent to prison, and brought here. Kantorovich, whom I have already mentioned (he was from Vilnius), exchanged a few words with the women. They opened up and said that this was Ponary, where not only the Jews of Vilnius had been shot but also Jews from Czechoslovakia and France. Our job would be to burn the bodies.”

Mainstream historiography knows of neither French nor Czechoslovakian Jews killed at Ponary. As mentioned in §2.3.3., the only French Jews claimed by the orthodox historians to have reached the occupied eastern territories departed Drancy for Kovno and Tallinn on 15 May 1944. Any French Jews present in Lithuania prior to that date must accordingly have reached that destination via one of the “extermination camps” of Auschwitz-Birkenau or Sobibór.

Interestingly we find in the “Ponary diary” of Kazimierz Sakowicz the following entry dated 4 May 1943 in which this Polish journalist reports on a conversation with Lithuanian militia members stationed at Ponary:[33]

“The Lithuanians say that they will have still more work to do, as Jews are to be brought here from abroad. Reportedly Jews from France, Belgium and so on are already being shot in the Fourth Fort in Kaunas [Kovno], where they were brought under the pretense that they would be transported to Sweden.”

That Belgian Jews were transported to Lithuania is confirmed by a news notice appearing in Aufbau on 28 August 1942:[34]

“Several hundreds of Belgian Jews, who had been deported to Wilna, were massacred by the Gestapo.”

According to Jewish historian Reuben Ainsztein,[35]

“entire train-loads of Czech, Dutch and French Jews were brought to what they believed to be the town of Ponary and exterminated there by German and Lithuanian killers.”

Ainsztein does not provide a source, but since neither Sakowicz nor Farber mentions transports of Dutch Jews to Ponary it seems likely that there exists further testimony concerning transports of foreign Jews to this place. In this context it should also be noted that Ponary is located only some 5 km north-east of the town of Vievis, where, according to rumors reported in the diary of Herman Kruk (cf. §3.3.1.), 19,000 Dutch Jews had arrived by 16 April 1943. As for the alleged mass shootings of foreign Jews at the forts around Kovno, we read in the Black Book:[36]

“Not only Kaunas Jews met their death in the mass graves near the forts; here the Nazis carried out the wholesale execution of thousands of Jews who had been driven there from the Lithuanian provinces, from Berlin, Vienna, France and Holland.”

The French Jews can be explained by the fact of Convoy 73 reaching Kovno in May 1944, but the mention of Dutch Jews is anomalous to exterminationist historiography.

A further witness stating that foreign Jews were brought to the Vilna area is the Lithuanian Jew and partisan Aba Gefen. On 16 May 1943 Gefen wrote in his diary:

“In the evening I visited Yonas Kazlovsky at Zhuk’s [a farmer]. He said that recently in Vilna 40,000 Jews—not from Lithuania, but from other countries—have been killed.”[37]

Again the date fits well with the Herman Kruk’s diary entry from 16 April 1943 and his subsequent entry from 30 April stating that 19,000 Dutch Jews deported to Lithuania had been “slaughtered” there (§3.3.1.).

3.3.12. Moses L. Rage

On 10 September 1944 a Latvian-Jewish engineer from Riga named Moses L. Rage (b. 1903) left a written testimony to a Soviet commission in Dvinsk (Daugavpilsk), in which we find the following passage:[38]

“Subsequently [in the spring of 1942 or later] there began to arrive in Riga a series of trains with Jews from Poland, Germany, Belgium, Denmark, Holland and other countries, which were taken off the trains and sent away on trucks to be shot. Their belongings were sent to the Gestapo. I estimate that the total number of foreign Jews killed in Riga and other parts of Latvia exceeds 200,000.”

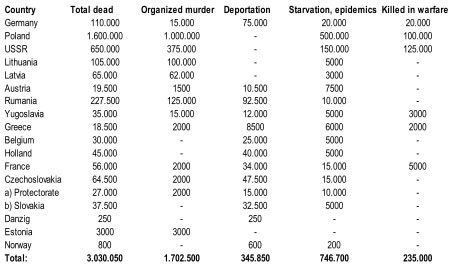

As mentioned in the first part of this article (§2.4.7.) no Danish Jews were ever “gassed”, and accordingly Rage could not have witnessed the arrival of Jews from that country in Riga, something which diminishes the value of this testimony. It seems possible though that the witness could have mistaken Norwegian Jews for Danish Jews. 346 Jews from Norway were allegedly “gassed” in Auschwitz in October 1942.

3.3.13. M. Morein

In his book on the Holocaust in Latvia, Bernhard Press provides the following brief summary of a testimony left by a certain M. Morein which is stored in the archive of the Jewish Information Center in Riga:[39]

“[…] while looking for the corpses of his parents in 1946 near the village of Kukas near Krustpils, he discovered in a mass grave corpses whose clothes bore French labels.”

It is not made clear whether with “French labels” is meant French Star of David patches or similar. The author of this article has not yet been able to access the testimony in question.

3.3.14. Szema G.

A Latvian Jewess identified in the court material only as “Szema G” testified in 1948 that groups of Belgian, Dutch, French and Hungarian Jews[40] were sent to the Lenta camp near Riga.[41] The value of this testimony is diminished by the fact that the witness incorrectly claimed that a crematory oven was installed in Lenta.

That foreign Jews were brought to the Lenta camp is supported, however, by other eyewitnesses. I have already discussed Jack Ratz’s mention of Polish Jews being sent to Lenta “straight from Poland” in the summer of 1943 (§3.3.9.). Another Lenta inmate, Abrahm Bloch, has stated:[42]

“To us came a small group of Jews from Vilna. For Lenta this was not a surprise. They brought to us Jews from the most different places.”

This indicates that foreign (i.e. non-Latvian) Jews were commonplace in Lenta. In this context one should note the following passage from a monthly report drawn up by the labor administration department of the Gebietskommissariat Riga for April 1943:[43]

“Lately there have been no new arrivals of Jews. […] Following the deployment of all Jewish auxiliary workers [Hilfsarbeiter] outside of Riga, and since the removal of Jewish skilled labor from the armaments industry—the production and supply of arms being of extraordinarily great importance—can no longer be justified, the influx of Jews from territories outside of Latvia is to be thoroughly welcomed.”

This acute need for Jewish labor would explain why Jews from Poland and possibly also from various Western European nations were sent to the Lenta camp in the summer of 1943. The last documented transport from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate to Latvia departed from Theresienstadt on 20 August 1942, although there are indications that a transport departing from Berlin on 26 October 1942 reached Salaspils near Riga (cf. §3.4.). Considering this, it seems decidedly odd that a lull in transports lasting a whole 5-7 months should be described using the word “lately” (“in der letzten Zeit”). Were there more transports of Jews to Latvia during the last months of 1942, or even at the beginning of 1943?

One might argue that any foreign Jews sent to Latvia in 1943 might have been Lithuanian. Herman Kruk, however, does not mention any Jewish transports from Lithuania to Latvia during that year, and as of 6 April 1943, the Kovno Judenrat secretary Avraham Tory had recorded only two transports of Lithuanian Jews to Latvia (both from Kovno to Riga): the first, consisting of 500 workers, on 6 February 1942; the second, consisting of more than 300 people, on 23 October 1942.[44] In his diary entry from 12 February 1943 Tory mentions a German demand that 1,000 Kovno Jews be sent to Riga,[45] but this demand was apparently rescinded, because Tory, who due to his position necessarily would be aware of any major transports from the Kovno ghetto, does not record any transports from the Kovno Ghetto (or any other place in Lithuania) to Latvia during 1943. Bloch’s statement hints at a transport of Vilna Jews to Riga, but this must have been small to escape Kruk’s attention. Possibly some Vilna Jews reached Riga after the liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto on 23 September 1943, i.e. five months after the above quoted labor administration report. There further exist no indications that Jews were sent from other parts of Reichskommissariat Ostland, or for that matter the Ukraine, to Latvia for work.

It should be mentioned here that Dutch Jews deported to the Baltic states in 1942-1943 apparently were alive not only in Kuremäe, Estonia (cf. 3.3.7.), but also in western Latvia in 1944, for in the Aufbau issue from 25 August 1944 we read:[46]

“Six hundred Jews, used by the Germans for forced labor on fortifications in occupied Latvia, were to be transferred to Liepaja. On the way there they were liberated by partisans. Most of them were deportees from Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Holland. Immediately after being liberated all of them joined the Latvian partisan units. This report comes from the Stockholm newspaper Baltiska Nyheter.”

3.3.15. Kalmen Linkimer

Another minor testimony concerning transports to Latvia is the diary of Kalmen Linkimer, a Jewish schoolteacher from Liepaja (Libau) who spent most of the second half of the war hiding in a cellar together with ten other Jews. In his diary entry from 10 June 1944, we read:[47]

“[The Latvians] so distinguished themselves through their blood thirst and brutality that Jews were sent from countries all over Europe to Latvia, Riga […]“

The use of the expression “all over Europe” certainly implies transports to Latvia of Jews from countries other than just Germany, Austria and the Protectorate. Unfortunately, Linkimer does not bring up the subject elsewhere in his diary.

3.3.16. Yehuda Lerner

Yehuda (Leon) Lerner is primarily known as a Sobibór eyewitness. He was deported to this “pure extermination camp” from Minsk in the second half of September 1943[48] under the “pretense” that the Jews in this convoy would be sent to work in Łódź.[49]

What is remarkable about Lerner is the fact that he had previously been sent from Warsaw to the occupied eastern territories. Lerner was born in Warsaw in 1926, and it was from there that he was sent to Belarus in the summer of 1942. In a brief, undated testimony (written sometime between 1951 and 1978)[50] presented by M. Novitch we read:[51]

“I was born in Warsaw in a family of six; my father was a baker. When war was declared, our life in the ghetto was similar to that of most Jews: unemployment, hunger and anguish. On July 22, 1943, tragedy began in the ghetto. The president of the Jewish council committed suicide and, on the same day, my father, my mother, one of my brothers and I were taken away to the Umschlagsplatz, the ghetto station, and were left in a building. My whole family was deported and never came back.

I was sent to a camp near Smolensk, in occupied Russia, where I remained for ten months. Our job consisted of building an airfield. For our work, we got a piece of bread and a bowl of soup. Hunger weakened us and prisoners who had no strength to work were taken to a wood and executed. Haim, a friend from the Warsaw ghetto, was with me. There also were German Jews, in transit through Warsaw. I told my friend, ‘Let us escape, we are doomed here.’

Four months later, on a dark night, we crossed the barbed wire, but we were caught and sent to another camp where we again found hard work, hunger and beating. We tried to escape a second time, managed to be free for several days, but once more were arrested and taken to the Minsk ghetto.”

The president of the Jewish Council of the Warsaw Ghetto, Adam Czerniaków, committed suicide on 23 July 1942. On the day before, the first train with Jewish deportees left Warsaw for the Treblinka “extermination camp”.

In 1979 Lerner was interviewed by Claude Lanzmann (in French, using an interpreter). A film of this interview was later released together with a published transcript,[52] but this does not contain the entire interview; especially the beginning has been cut short. Fortunately, a complete transcript is available online. In this Lerner dates his deportation to July 22:[53]

“[…] all starts on July 22, 1942, at the moment when they make us leave the Warsaw ghetto; they gather us at the Umschlagsplatz and they tell us that they are going to send some of us off, they do not know where yet; at this moment, I am still with my parents, with my family, but very quickly we are separated, they send me to one side, my parents and my family to the other, and from that moment I am alone. They tell us that in some days they would send us into a work camp, and effectively, after these few days still spent in Warsaw, we leave for Russia.”

This indicates that the transport in question departed from Warsaw sometime during the last week of July. Later in the interview the period between the arrest and the departure is stated to have been “several days”. Lerner further tells Lanzmann that the convoy consisted of “some thousands of young people”, all able to work.[54] The journey is described as follows:[55]

“Lerner: And so, it is there that everything started; for nearly a week, we traveled in these freight cars; each day we were given a little water through the door. After we were placed in the freight cars, they distributed to us a loaf of bread each, and soon we arrived in Belorussia and we were unloaded for work, the place where we arrived was located near an old airport.

Lanzmann: What was it called?

Lerner: The name of the place, I do not remember exactly, in any case it was an airfield and we were working in construction, we were constructing buildings; the conditions were very hard, very little to eat, the Germans on the spot fired on the Jews, without reason, and in particular the pilots when they returned in the evening, got drunk and amused themselves by shooting, firing on the Jews, in the head in general.

Lanzmann: This was a military airport?

Lerner: Yes, military.

Lanzmann: And this, this is the first place where he [i.e. Lerner] had been, after having left Warsaw?

Historian Christian Gerlach states that the transport carrying Lerner arrived in Bobruisk on 28 July and that a part of this convoy continued on to Smolensk.[56] The only source that Gerlach gives here, however, is the Lerner account found in the Novitch anthology, which does not mention any stop-over in Bobruisk. Moreover Gerlach writes that the 28 July Bobruisk transport together with a previous transport of 961 Jews from Warsaw to Bobruisk on 30 May 1942 consisted of in all some 1,500 people,[57] so that the latter convoy would have contained approximately 540 Jews—in contrast with Lerner’s statement to Lanzmann that the deportees of his transport numbered “some thousands”. Apparently the only thing certain about this transport is that it took place, since there is no doubt that Lerner later was sent to Sobibór from Belarus. Thus we have only Lerner’s personal assurance that the train did not stop anywhere on the way from Warsaw to Smolensk—for example in Treblinka.

On 17 August 1942 the clandestine Polish newspaper Informacja Bieżąca mentioned that 2,000 “skilled workers” had been sent from the Warsaw Ghetto to Smolensk on 1 August 1942. Some weeks later, on 7 September, the same newspaper reported that two transports carrying a total of some 4,000 Jews had been sent from Warsaw to work on military installations in Brzesc and Malachowicze.[58]

This raises the question: were there perhaps not one, but two transports from Warsaw to Smolensk during the first week of the great evacuation—one with some 540 Jews that reached Bobruisk on 28 July and another with 2,000 Jews, that departed from Warsaw on 1 August, travelling directly to Smolensk?

Lerner’s statement that there “were German Jews” in the camp in Smolensk who had arrived there from Warsaw is intriguing. From the diary of the aforementioned Warsaw Judenälteste Adam Czerniaków we know that during the spring of 1942, some 4,000 Jews from the territory of the Reich and the Protectorate were deported to the Warsaw Ghetto. On 1 April there arrived “1,000 expellees from Hannover, Gelsenkirchen etc.” who were “put in the quarantine at 109 Leszno Street”. This convoy consisted of “older people [but no-one older than 68], many women, small children”.[59] On 5 April there arrived “1,025 expellees from Berlin”, “mainly older people, partly intelligentsia”. These were also put in the quarantine at Leszno Street, which now contained in all “2,019 persons” (implying that the first convoy consisted of 994 deportees).[60] On 8 April Czerniaków visited the Jews “from Berlin, Frankfurt, Hannover, Gelsenkirchen etc.” in the quarantine, distributed candy to the children and “addressed the youth” among them.[61] Two days later “150 young German Jews” were sent to “Treblinka”,[62] by which is no doubt meant the labor camp Treblinka I, as the “extermination camp” Treblinka II would not open until three and a half months later. Considering the descriptions of the two first German convoys, these 150 deportees must have made up most if not all of the youths among the quarantined German Jews. On 16 April a third transport of “about 1,000” German Jews arrived in the ghetto.[63] On 18 April Czerniakow was called to see the ghetto commandant Auerswald about the German Jews:

“He gave me a list containing 78 names from the last transport; these people are to be sent to Treblinka. Besides he gave me two letters from the workers who are already there. One is asking for phonograph records, the other for tools.”[64]

On 23 April a “transport of 1,000 people arrived from Bohemia”.[65] Almost a month later, on 23 May, Czerniaków noted that “thirty Jews” had been sent to Treblinka, but he neglected to mention whether these were Polish or German Jews.[66] Then finally on 16 July 1942, six days prior to the start of the great evacuation, the Judenälteste mentioned in his diary that 1,700 German Jews had been released from the quarantine.[67]

Very little documentation on the great Warsaw evacuation has survived. We do not know when the German Jews in the ghetto were sent to Treblinka. It may be that the German Jews from Warsaw whom Lerner met in Smolensk were identical with those 150 or so young Jews who had been sent to Treblinka I in April, and that those for some reason had been transferred east, but it is also possible that they had reached Russia via the Treblinka “extermination camp” during the first days of the deportations.[68] A member of the Warsaw ghetto police noted in his diary:[69]

“The tenants of two hostels [that housed Jewish refugees from Germany and Czechoslovakia] received a day’s notice that they must leave on the morrow. They had already undergone so many moves from city to city and country to country that they showed no signs of despair or fear. Warsaw or Vilna, Smolensk or Kiev—it was all the same to them.”

Is it just coincidence that Smolensk is mentioned here as a possible destination?

It should be mentioned here in passing that there is testimonial evidence for the presence of German Jews also in Bobruisk. In 1971 a German witness testified that he had met and spoken with a German Jew from Mönchengladbach in the SS-Arbeitslager Bobruisk.[70] The Jews from Mönchengladbach were sent to Auschwitz, Łódź, Riga, and Theresienstadt.[71] Those sent to Riga went there via Düsseldorf, and included the witness Hilde Sherman-Zander (§3.3.2.).[72]

3.3.17. Inge Stolten

Inge Stolten (born 1924) was a German stage actress and playwright. During the war she performed for German troops in Germany as well as at theatres in the occupied territories. In late July 1943 she was sent to Minsk,[73] where at the Minsk Theatre she got into contact with some German Jews from the Minsk ghetto who worked backstage. In the description of the Minsk ghetto found in her memoirs, Stolten mentions also Dutch Jews:[74]

“I heard of Dutch Jews who still believed that their furniture would be forwarded to them as promised, who discussed how they would be able to fit their great armchairs into the all-too-small rooms. Thus almost all of them hung on to some kind of illusion, nourished hopes and felt secure once they had escaped something.”

For more on the presence of Dutch Jews in Minsk, see §3.5 below.

3.3.18. Tsetsilia Mikhaylovna Shapiro

The testimony of Dr. Tsetsilia Mikhaylovna Shapiro, a former inmate of the Minsk Ghetto, was recorded on 20 September 1944 by A.V. Veysbrod. This witness, who escaped from Minsk in early November 1942, stated that French Jews had been present in this city.[75]

3.3.19. Avraham Tory (Golub)

Avraham Tory (aka Avraham Golub, b. 1909) served as secretary of the Jewish Council in the Kovno Ghetto. During the period 1941-1944 Tory kept a diary in which he also reproduced several orders and reports from the Council as well as the German ghetto administration.

In Tory’s diary entry from 14 July 1942 we read:[76]

“Four Jews from Lodz have been brought to the [Kovno] Ghetto hospital for surgery. They had spent a long time in a labor camp.”

On 30 July 1942 Tory again wrote of Łódź Jews in Lithuania:[77]

“The Lodz Jews who had been employed at the construction of the Kovno-Vilna highway and were transferred to Riga will be replaced by 500 workers from the Ghetto.”

In the same entry, Tory writes:[78]

“Five Jews who risked their lives by escaping from a labor camp, where they had been employed at highway construction, arrived in the Ghetto, having traveled by various routes. The inmates of this labor camp had been transferred by road to Riga, and fifty Jews escaped during the transfer. As they jumped off the trucks, they were shot at. Two of the escapees waded into the [unnamed] river and remained hiding there, submerged in the water up to their necks. After the first danger passed, they entered the forest and hid there. Then they traveled by roundabout paths until they reached Kovno.”

We further learn about the unnamed labor camp the following:[79]

“The camp commandant pretended to be the friend of workers. In reality, he disposed of everyone who, for different reasons, fell behind in his work. One day twenty people were killed by injections of poison, having been told beforehand that they were exhausted and sick and needed some rest. Those who asked to be taken to a physician were taken to the forest and shot. Only four inmates were brought to the Ghetto hospital for surgery; there they remain as of now.

The Council extended assistance to the inmates of this labor camp. This assistance was of some help. But the inmates were desperate and availed themselves of every opportunity to flee, despite the risk to their lives.

Fifteen of those people are now in the Ghetto. First, they were cleaned of lice at the lice disinfection center. They have also received clothes, which enable them to conceal their condition and status in the Ghetto. They must also be protected from the evil eye. At the same time, however, they present the [Jewish] Council with a problem: should the Gestapo find out about their presence in the Ghetto, their fate will be one and the same—death.”

The above diary passages indicate that several hundreds of Jews from Łódź were confined in a labor camp somewhere between Kovno and Vilna, not far from a river, and that this group was transferred to Riga sometime in late July 1942. Likely Tory refrained from naming the camp here due to concerns of security, as mentioned in the diary entry itself.

In this context one may recall Herman Kruk’s diary entry (cf. §3.3.1.) from 4 July 1942 reporting on the presence in Vilna of two young Jews who had been deported from Łódź in March the same year, and who had escaped from an unnamed labor camp around the 25th of June. Needless to say the escapees mentioned by Tory and the escapees with which Kruk came into contact might have come from two different labor camps.

Which camp then is Tory referring to? Later in the diary he mentions that the camps Miligan (Milejgany), Vievis and Zezmer (Ziezmariai) employed “thousands of Jews” working on the construction of the Kovno-Vilna highway; in charge of these labor camps was “the Kovno branch of the Todt organization.”[80] Much points to Vievis being the camp in question, because at the end of the 30 July 1942 entry we find the following isolated sentence:[81]

“Five Jews from the labor camp near Vievis arrived in the Ghetto. They were given clothes and underwear.”

It seems highly unlikely that two groups of each five Jews with ragged clothes had arrived from two different labor camps to the Kovno Ghetto on the same day. Tory – who was a lawyer by profession—may have thought it safe to mention the name of the camp in an isolated sentence where the circumstances of the arrival of the five Jews were not made explicit. That the Jewish Council of Kovno did in fact “extend assistance to the inmates” of Vievis is clear from the diary entry of 2 July 1943, in which we read that “Yellin, the representative of Vievis camp” visited the Kovno Ghetto “once every two or three weeks to collect wooden shoes, underwear, and other supplies from our welfare department” and that “Once in a while, patients from Vievis camp are admitted to our Ghetto hospital”.[82]

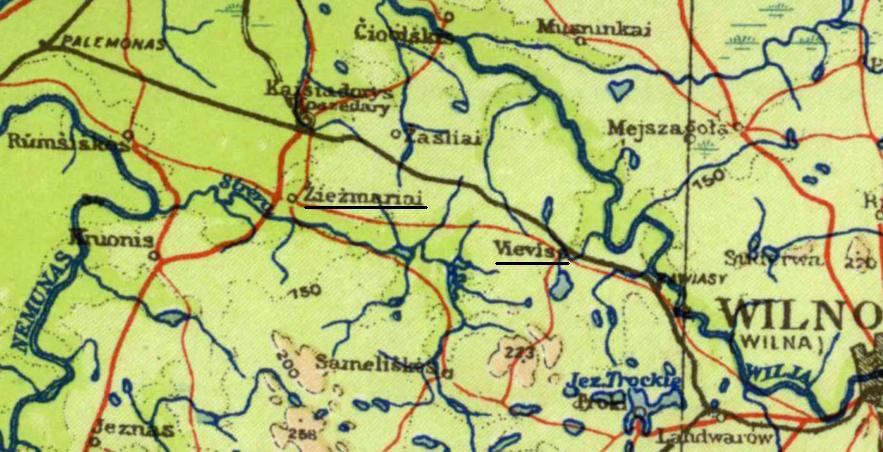

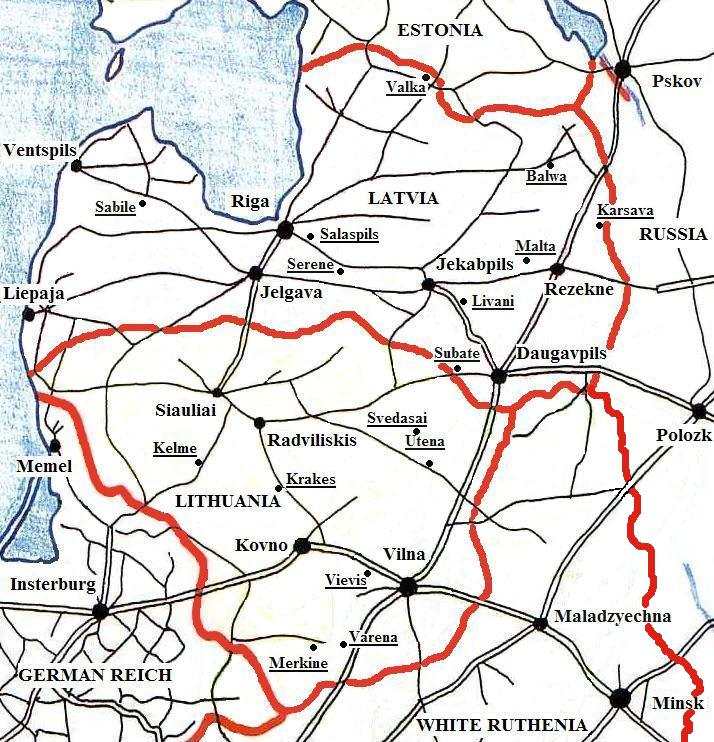

A look at a map of the Vievis area (Illustration 1) shows a wooded area to the east of the town, which may be the “forest” where sick inmates reportedly were taken to be shot. The “river” in which escapees hid themselves might have been the Streva, a tributary of the Nemunas River. The Streva runs along the road from Vilna to Kovno at a shorter distance for a stretch between Vievis and Rumsiskas (cf. Illustration 2).

Finally, in the diary entry from 10 December 1942, we read:

“A young girl by the name of Zisling has come to the Ghetto from the labor camp in Vievis.”[84]

Without at least a given name and an approximate date of birth it is nigh unto impossible to identify this individual. Nonetheless we may note that a search of the online Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names,[85] which reportedly contains records of close to 3 million individuals—with the caveat that “some people appear in more than one record”)[86]— produces a mere 29 results for the surname “Zisling” with variants (Cizling, Zysling, Tzizling), whereof almost half are duplicates. We are thus dealing with a very rare Jewish surname. Of these search results, the following pertain to young girls:

- Lea Cizling, born to Beniamin and Khana Cizling, nee Pinta. She reportedly died in Skuodas, Lithuania, in 1941, aged 11.

- Zelda Zysling, born in April 1926 in Klodawa,[87] Poland, to Baruch and Sara Zysling nee Skowronski. Reportedly killed in Chełmno aged 14.[88]

- Zalma Zysling, the sister of Zelda Zysling, born 19 December 1930, also supposedly gassed at Chełmno.[89]

- Deborah Zisling, sister of Zelda and Zalma Zysling, supposedly gassed at Chełmno in 1942 at the age of 19.

- Pese Zysling, born in Klodawa in 1924, supposedly gassed at Chełmno in 1942.

This inconclusive yet notable information compels the question: Were Jews who had been transited via Chełmno still present in Vievis in late 1942? Did the transfer to Riga in July 1942 perhaps encompass only the able-bodied or skilled workers? Research into local archives might possibly provide more information on transports to and from the Vievis camp.

The diaries of Avraham Tory and Herman Kruk indicate that the Vievis camp served as a major destination and/or transit point for Jews deported to the East: First in 1942 Jews from the Warthegau district were sent there via Chełmno, and then in early 1943 Dutch Jews reached the camp via Auschwitz and Sobibór. Many of these Jews were apparently employed in the construction of a highway between Vilna and Kovno. This brings to mind the following passage from Himmler’s speech in Bad Tölz on 23 November 1942:

“The Jew has been removed from Germany; he now lives in the East and works on our roads, railways etc.”[90]

A Partial List of Camps with Jewish detainees in Lithuania

Abbreviated Main Sources

- T: A. Tory, Surviving the Holocaust (Harvard University Press 1990).

- K: H. Kruk, The Last Days of the Jerusalem of Lithuania (Yale University Press 2002)

- NL: Martin Weinmann (ed.), Das nationalsozialistische Lagersystem.[91]

List of Camps

- Aleksotas – labor camp in western Kovno suburb at the site of an airfield (NL p. 665, T p. 455).

- Babtai – camp where some 1,500 Jews were employed at an “Heeresbaudienststelle” (Army construction bureau).[92]

- Batcum – camp belonging to the Siauliai (Schaulen) Ghetto with 500-1,000 inmates, established 1942, closed 1944 (NL, p. 665).

- Bezdany – peat-digging camp 25 km from Vilna (K, p. 120, 486).

- Biała Waka – peat-digging camp 14 km from Vilna (K, p. 120, 407).[93]

- Darbenai – camp in the Kretinga district.[94]

- Demitrau (Dimitravas) – camp in the Kretinga district.[95]

- Ezereliai (Ezerilis) – subcamp to KL Kauen (Kovno) with accommodations for 1,200 Jews.[96]

- Jonava – labor camp with some hundred inmates.[97]

- Kacergin – Jewish tree-felling unit located in suburb of Kovno (T, p. 114).

- Kailis – “Jewish labor camp” inside Vilna (K, pp. 134-135).

- KL Kauen (Kovno) – concentration camp replacing the liquidated Kovno Ghetto in June 1943, closed on 25 July 1944 (NL, p. 299).

- Kazlu-Ruda (Raudondvaris) – subcamp to KL Kauen with 300 Jewish inmates some 20 km south of Kovno, established in early 1944.[98]

- Keidan – labor camp connected with the construction of an airfield (T, pp. 448-453). May be the same as Kedanen/Kidarniai (NL).

- Kiena – peat-digging camp, likely near Vilna, apparently run by Organization Todt (K, p. 120, 366, 630). Likely identical with the Keni labor camp mentioned by Tory, who asserts that all of the camp inmates, “300 in all”, were burned alive in July 1943 (T, p. 430).

- Koschedaren (Kaisiadorys) – Tory gives the name as Koshedar (T, p. 482), but also as Kaisiadorys: “the peat-digging camp at Kaisiadorys, where 350 Ghetto residents do forced labor” (T, p. 454).

- Kybartai – small town on German border with Jewish camp or labor unit (T, p. 113).

- Linkaiciai (Linkeitz) – labor camp halfway between Kovno and Siauliai where Jews worked in army factories and warehouses, a sugar refinery and with peat digging (T p. 126, 460).

- Marijampolé – Army camp in the vicinity of this city to which 400 Kovno Jews were transferred in late September 1943 (T, p. 482).

- Miligan (Milejgany) – labor camp for road construction (T, pp. 389-390, 492).

- Nowa Wiljeka – Jewish labor camp in the town of the same name (K, p. 485).

- Oszmianka – labor camp run by Organization Todt, located near the town of Oszmiana (K, p. 621).

- Palemonas – peat-digging camp 10 km from Kovno; a brick factory was also located here (T, p. 58, 60, 92, 482).

- Panemune – labor (possibly peat digging) camp.[99]

- Panevezys (Ponevezh) – City in northern Lithuania where a ghetto and later a Jewish camp was located; according to the witness Reska Weiss there lived as many as 30,000 Jews in the camp in the summer of 1944, mainly Baltic Jews.[100]

- Petrasunai (Petrasun) – Kovno suburb where Jews worked in a paper factory and at an electric power plant, accommodations for 5,000 Jews were reportedly under construction here in August 1943 (T, p. 116, 188, 455).

- Podbrodzie – labor camp or site to where 400 Vilna Jews were sent in early May 1942 (K, pp. 286-287).

- Porubanek – groups of Jews worked here in early 1942 with unpacking and sorting weapons and ammunition (K, p. 173).

- Provienishok (Pravieniskis) – labor camp 20 km south-east of Kovno (T, p. 115). This is likely the same camp as Prawienischken or Proveniskaiai, which according to NL (p. 666) housed 5,000 – 6,000 inmates “working in the woods”; it was established in 1941 and closed sometime in 1944 .

- Radvilishok (Radviliskis) – ghetto and peat-digging labor camp in central Lithuania, railway junction (T, p. 113).

- Rudziszki – labor camp (K, p. 629).

- Rzesza – peat-digging camp 15 km from Vilna with a few hundred Jewish detainees (K, p. 118, 366).

- Sanciai (Schantz) – labor camp in a suburb of Kovno (T, p. 318, 455, 482, 501).

- Siauliai (Schaulen) – the ghetto in this city in north-western Lithuania was the third largest in the country; after its liquidation it was replaced on 17 September 1943 with Concentration Camp Schaulen. Inmates evaucated to Stutthof on 21 July 1944. According to the aforementioned Reska Weiss it held as many as 30,000 Jews in the summer of 1944.[101]

- Sorok Tatary – forestry labor camp 15 km from Vilna (K, p. 400).

- Swieciany – Jewish labor camp about 80 km from Vilna (K, p. 485, 513).

- Veivirzenai – camp located between Taurage and Kretinga employing Jewish women in agricultural labor (K, p. 483).

- Vievis – Jewish labor camp near the town of Vievis (cf. §3.3.1.).

- Volary – camp for Jews (NL, p. 299).

- Vyzuonos – an agricultural camp or labor unit called the “Red Plantation” was located near the town of Vyzuonos in 1943.[102]

- Zasliai – Jewish labor camp run by Organization Todt (K, p. 485, 533).

- Zatrocze – agricultural/peat digging camp not far from Trakai (Troki), which is located some 20 km west of Vilna (K, p. 346, 447).

- Zezmer (Ziezmariai) – labor camp for road construction with at least 400 Jewish detainees in early May 1943. Located 50 km north-west of Kovno. The camp was technically affiliated with the Vilna Ghetto but received aid from the Kovno Ghetto Council (T, p. 162-163, 329). In early May 1943 the camp housed 1,200 Jews, “including 180 children and a number of old people”, brought there from Oszmiana and other towns in the Vilna district; some of these were later transferred to Dno near Pskov, 680 others to the Kovno Ghetto (T, p. 328, 376). According to H. Kruk the camp housed 1,200 – 1,500 Jews (K, p. 554). It appears to have been at least formally run by Organization Todt (K, p. 533).

Aside from the three major Lithuanian ghettos of Vilna (Vilnius), Kovno (Kaunas) and Schaulen (Siauliai) there existed a number of minor ghettos, many of them in the small part of northwestern Belarus which had been incorporated into Generalbezirk Litauen: Soly (T pp. 273-274, 486), Oszmiana (K p. 387), Michaliszki (K, p. 486), Smorgonie (reportedly there existed two ghettos in this town; K, p. 629, NL p. 666), Krewo (NL ibid.), Ziezmariai (ibid.) and Nieswiez (ibid.).

Reading orthodox literature on the Holocaust in Lithuania one generally gains the impression that there existed only a handful camps in this country during the German occupation. However, as seen above, a minor survey of some easily available sources clearly indicates that there existed at least some 43 camps with Jewish detainees on Lithuanian soil. Of the camps listed some 90% were located in south-eastern Lithuania, near Vilna or Kovno. How many camps existed in other parts of the country that the authors of these sources were either not aware of or had no reason to mention?

A possible explanation for the seeming ignorance of the mainstream historians on this issue could be that the large number of camps does not square very well with the firmly established belief that some 75% of the Lithuanian Jews had been killed already by early 1942, and that the vast majority of the survivors were housed in the three major ghettos.[103] This is not to say that all the Lithuanian Jews allegedly murdered by the Einsatzgruppen were in fact transferred to these labor camps. While some of them probably were indeed shot—as communists, resistance members, hostages, carriers of epidemic diseases, or for other reaons—many may also have been deported out of Lithuania. Herman Kruk, in a diary entry dated 11 July 1942, mentions a Vilna Jew living undercover with “Aryan” papers in Belarus, according to whom “a lot of Jews from Vilna and Kovno are working in Minsk”.[104] In the April 1942 issue of Contemporary Jewish Record we read concerning the “over 30,000” Jews removed from the Vilna ghetto (up until February 1942) that “it is believed that half are now in labor camps on the Soviet front, and the remainder have either been interned or executed”.[105] According to mainstream historiography these Jews were slaughtered en masse at Ponary.

As for the populations of the respective camps, there is a near-total lack of reliable figures. The few available figures are frequently based not on documentary sources but witness testimony. One should note that even if such estimates are taken to be more or less correct, they typically reflect the inmate population at only one given time; needless to say, the populations as well as holding capacities of the camps could have fluctuated. Future archival research may perhaps bring more clarity on this issue. It is also possible that aerial photographs, which we know were taken over Lithuania in 1944,[106] could help out with locating camps and estimating their holding capacities.

To conclude: It is certainly not out of the question that a large number of Polish and Western Jews said to have been “gassed”— perhaps even some hundreds of thousands—were interned in Lithuanian camps and ghettos during the years 1942-1944.

3.4. Historians and Witnesses on the Presence of Foreign Jews in Salaspils and Other Latvian Camps

Historian Franziska Jahn has summarized the currently held historiographical picture of the Salaspils camp, located near the Latvian capital Riga, as follows:[107]

“Salaspils was the second camp [the first being Jungfernhof] outside of the [Riga] ghetto, to which foremost male ‘Reich Jews’ between the age of 16 and 50 were deported. According to the estimates of survivors there were 1,500 inmates in Salaspils. They constructed the camp and worked at the nearby railway station with sorting the luggage from arriving Jewish transports. From the summer of 1942 Salaspils served as a Polizeihaeftlager [police custody camp] for Latvians and Russians.”

In their study The ‘Final Solution’ in Riga, originally published in German in 2006, historians Andrej Angrick and Peter Klein devote two chapters to the Salaspils camp. Here we learn that the camp, assigned to the Regional Commander of the Security Police (KdS) Latvia, was constructed starting September 1941 and meant to house Latvian political prisoners as well as Latvian Jews and Jews brought from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. Originally the camp was planned to hold about 25,000 inmates. A POW camp, Stalag 350, which held some 40,000 prisoners, was already located nearby.[108] By mid-January 1942 at least 1,000 Jews were working in the camp.[109] On 2 February 1942 a status report from the office of the Territorial Commander of the Security Police and Security Service (BdS) Ostland advised that construction was underway at Salaspils on

“a large camp for about 15,000 inmates, which will be completed around the end of April and is designated at the moment to take in the Jews coming from the Reich. Whereas a part of the camp is to serve immediately as an enlarged police prison, the camp would be completely available as an expanded police prison and correctional camp after the deportation of the Jews, which is expected toward the end of summer.”[110]

The work on this camp, however, did not progress as planned. On 2 May 1942, 300 Jews were transferred from the Riga ghetto to Salaspils for cutting peat. By the end of June there were only 675 inmates in the camp, whereof some 400 were German and Austrian Jews. The KdS Latvia now had to admit to Berlin that after nine months barracks for only 1,000 inmates had been built, and that barracks for only 500-1,000 more inmates could be added in the near future.[111]

In the autumn of 1942 the German and Austrian Jews were gradually withdrawn from Salaspils. By December there were 1,800 inmates in the camp, most of them Latvians brought in from the Riga Central Prison and elsewhere.[112]

As we have already seen above in §3.3.5., the former Higher Leader of the SS and Police of Reichskommissariat Ostland, Friedrich Jeckeln, stated during his interrogation on 14 December 1945 that between 55,000 and 87,000 Jews “from Germany, France, Belgium, Holland, Czechoslovakia, and from other occupied countries” had been brought to Salaspils and “exterminated” there in the period from November 1941 to June 1942.

Contemporary Latvian experts, however, estimate the number of Salaspils victims at only some 2,000.[113] This of course does not exclude the deportation of tens of thousands of Western Jews to the camp, providing that a) the Jews were not murdered there, and b) that most of the arriving Jews were transferred on to other camps or ghettos. Salaspils would in that case serve as a transit station for Jewish transports, similar to for example the Vaivara camp in Estonia.

Latvian-American historian Andrew Ezergailis unsurprisingly dismisses the notion that other groups of foreign Jews may have been deported to Latvia:[114]

“It is a Soviet invention that 240,000 Jews were sent to Latvia and murdered there. To begin with, there was not enough housing in wartime Latvia to accommodate, even on a temporary basis, numbers of that scale. The two larger concentration camps, Salaspils and Mezaparks (Kaiserwald), even after being completed, could accommodate only about 6,000 each. And the Riga Ghetto, after the killing of Latvia’s Jews, was never again filled up to its original population of 29,000. A makeshift camp was created in Jumpravmuiza [Jungfernhof], but that housed at its peak no more than 4,000.”

What Ezergailis fails to consider is the fact that there existed a number of other, smaller camps in Latvia (for example Strasdenhof, Dundaga I and II, Lenta, Spilve, Eleja-Meitene), as well as minor ghettos such as those in Liepaja and Krustpils. According to a brief report which appeared in the February 1945 issue of the Swedish-Jewish Judisk Krönika there existed in the summer of 1944 no less than 21 camps in the Riga district alone, housing at least 15,000 Jews “from Western Europe” as well as 3,000 Hungarian Jewesses.[115]

Ezergailis likewise completely ignores the possibility that such deportees may have been accommodated only for a while in Latvia and later sent elsewhere, for example to workplaces near the Leningrad front. Something like this is in fact hinted at by a brief report which appeared in the February 1943 issue of Contemporary Jewish Record:[116]

“Systematic deportation of all Jews who remained in Latvia, including those brought from Germany, Holland and Belgium was reported Nov. 19 [1942]. The first step in the policy of extermination was taken Nov. 28, 1941, according to the Manchester Guardian (Oct. 30), when the Nazis established an ‘inner ghetto’ in Riga, and began to use the main ghetto as a transit camp for Jews from Central Europe.”

We note here the (from an exterminationist viewpoint) anomalous presence of Dutch and Belgian Jews in Latvia, as well as the claim that Riga served as a transit station for foreign Jews. If the mentioned transfer did indeed take place it cannot have been complete, at least not in the case of the German (and Austrian) Jews, since it is well documented that there were still thousands of them left in Latvia in summer 1944 (see also §3.3.14. for a report on the presence of Dutch Jews in Latvia in 1944).[117] This report, together with that appearing in the 16 October 1942 issue of Israelitisches Wochenblatt für die Schweiz (according to which “Jews from Belgium and other western European countries” who arrived in Riga “moved on immediately to other destinations”; §3.1.2.) indicates that the Dutch Jews sent to Riga were not shot in the nearby Bikernieki Forest upon their arrival, as claimed by Hilde Sherman-Zander (3.3.2.), but transferred to other ghettos or to labor camps.

Considering the abovementioned possibilities, it is definitely not out of the question that a total of some hundreds of thousands of foreign Jews were indeed transported to Latvia in the period of 1941-1944. Ezergailis’s report that there exist no known mass graves containing hundreds of thousands of foreign Jews, or court testimonies or documentation on this hypothetical mass murder,[118] needless to say, merely points to the fact that such deportees were not killed en masse.

The fact is, that the historiographical knowledge of the Salaspils camp is exremely scant. Even Angrick and Klein have to admit that “the history of the Salaspils camp and its different groups of inmates is almost unknown.”[119] Their three Latvian colleagues Karlis Kangeris, Uldis Neiburgs and Rudite Viksne state in an article from 2009 that the administrative records of the Salaspils camp have not been preserved (presumably the documents were destroyed by the Germans at the time of the retreat in autumn 1944), and that the scattered preserved documents (deriving from various German occupation authorities) are not sufficient to reconstruct the history of the camp.[120]

There are indeed some Jewish historians who maintain or at least accept as possible the notion that Western Jews from countries other than the German Reich and the Protectorate were deported to Latvia. Bernhard Press, who himself grew up as a Jew in Riga during the war, writes in his study on the Holocaust in Latvia:[121]

“As for the number and origin of other foreign Jews [i.e. other than Jews from Germany, Austria and the Protectorate] who were murdered in Latvia, no official data of any sort exist, and rumors about them are still awaiting confirmation. As has already been indicated, in recent years numerous large and small mass graves have been discovered at various locations in Latvia, but these have yielded no new information because as a rule it was impossible to identify the victims. It must be pointed out here that a leitmotif in the relevant literature is the statement that Jews from France, Belgium, Holland, and even Norway died in Latvia besides those from Germany and the countries of Eastern Europe. Such statements can be found not only in the books of M. Kaufmann and M. Birze and the aforementioned KGB brochures, but even in the personal minutes of the interrogation of F. Jeckeln on December 14 and 16, 1945. […] It is known that there were also Lithuanian and Polish Jews in the Riga ghetto and the billets [= work camps/commandos in the Riga area…]. Jews from Romania and Yugoslavia were also reportedly exterminated in Latvia. […] As has been mentioned, F. Jeckeln […] claimed not to know how many foreign Jews had been brought to Riga. Thus the question of the number and origins of the Jews who were deported to Latvia and murdered there remains largely unanswered. Nor do we have a precise answer to the question of how many of the Latvian Jews in the territory occupied by the Germans survived the war.”

That Yugoslavian Jews were brought to Latvia is reportedly confirmed by eyewitness testimony. On 1 January 1943 the weekly exile-German newspaper Die Zeitung reported:[122]

“Now a man who escaped from the Riga Ghetto to neutral foreign soil [likely Sweden] reports that transports of Yugoslavian Jews have arrived in Riga.”

In the same news article we read that

“a report appearing in Gardista, the newspaper of Sano Mach, the Slovakian Minister of the Interior, informs that also Croatian Jews are detained in two towns in eastern Poland.”

This would imply that the Jews sent to Riga were Serbian Jews. Since the surviving Serbian Jews were most likely deported to Transnistria or the Ukraine (cf. 2.4.5.), it seems more plausible that they were in fact Jews from “Greater Croatia” (considering that a Yugoslavian state of which Croatia was part had existed for more than twenty years prior to the war, confusion on this issue would be understandable). If so, they were part of the 4,972 Croatian Jews deported to Auschwitz in the summer of 1942 (cf. 2.4.4.).

It should be noted that “eastern Poland” could well refer to the western part of Generalbezirk Weissruthenien, which used to belong to Poland. We may also note in passing that, according to Reuben Ainsztein, Yugoslavian Jews were detained in the Janów camp near Lwów (Lviv) in the south-east part of the General Government (now in the Ukraine).[123]

The presence of Polish Jews in the Riga Kaiserwald camp and its subcamps is confirmed by one of the leading Latvian Holocaust historians, Margers Vestermanis, who writes:[124]

“The number of prisoners was reduced considerably through Selections, especially in the summer of 1944, as the front drew closer to Riga. Concerning the many Selections only a single, peculiar document has been preserved: an inscription in Russian on the inside of a locker in the subcamp Strasdenhof (Strazdumuiza): ‘I, Abraham Grafman from Warsaw, am now on August 3 among a group of 900 Jews, who are being taken away to be shot.'”

Here we may recall that the witness Jeanette Wolf states in her memoirs that Polish Jews were kept in the Strasdenhof camp, that another witness, Josef Katz, repeatedly mentions the presence of Polish Jews in the Riga Ghetto and the Kaiserwald camp (cf. §3.3.1.) and that Jack Ratz speaks of the arrival of Polish Jews (who had come “straight from Poland”) at the Lenta camp outside Riga in the summer of 1943. We may also note that the Yad Vashem Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names[125] lists an Abraham Grafman from Warsaw (b. 1904), who supposedly perished in 1943—the entry states that he died in Warsaw, but the relative who filled in the form apparently did not know Grafman very well, since the form has the year of birth altered from 1900 to 1904. Could Abraham Grafman have been deported to Latvia via Treblinka?

Vestermanis further writes:[126]

“Regarding Eleja-Meitene [a subcamp of KL Kaiserwald in the Mitau/Jelgava district] the following additional information may be found in the Historical Archives in Riga: The camp, consisting of 16 dilapidated barracks, was located near a ‘Machine and Tractor Station’ in Eleja. The approximately 3,000 Jewish prisoners from Lithuania and Poland were chiefly employed in laying rail tracks and with repairment of tracks. The camp was in use between October 1943 and June 1944. Nothing is known about the subsequent fate of the prisoners.”

How these Polish Jews had reached Latvia, Vestermanis leaves unexplained. According to information furnished by the International Tracing Service in Arolsen the inmates in the Eleja-Meitene camp (said to be located 40-50 km from Mitau) were employed by the firms Rippel, and Berger & Ottlieb.[127]

German historians Helmut Krausnick and Hans-Heinrich Wilhelm mention—without providing a source or any further explanation—that Jews were brought from Holland to the Baltic states.[128]

Historian and former German-Jewish Riga-ghetto inmate Gertrude Schneider has the following to say about Salaspils camp and the child inmates who reportedly became victims of medical experiments conducted there:[129]

“By late summer of 1942, Salaspils had become primarily a camp for Latvian political prisoners and Russian prisoners of war. It also served as a transit center for subsequent Jewish transports on their journey to death in the forest. […] Postwar examinations of exhumed bodies revealed that various poisons had been tested on the small victims. Tags worn by the children were found in the forest nearby and at Salaspils. They were made out of aluminum and were marked, in many cases, ohne Eltern (without parents), thus identifying the children as orphans. While many of the names on these tags were Jewish, there were quite a number that had to be of Slavic origin, due to the fact that some of the transports had come from Belorussia and from the Theresienstadt Ghetto in Czechoslovakia. Most of the transports came from the Reich, but some had come from as far away as France.”

I will note here in passing that only one transport from Theresienstadt to Riga in the summer of 1942 is documented: it was given the transport code Bb and departed on 20 August 1942.

Elsewhere Schneider writes:[130]

“While transports of Jews from all over Europe were going to be coming to Riga until late fall of 1942, they would be liquidated immediately, except for small children, who were then housed in one big barrack in Salaspils and used for medical experiments.”

Lotte Strauss recounts a conversation with Schneider in 1999 during which the Holocaust survivor-cum-historian told her that

“during the fall of 1942, 40,000 Jews, mostly from Germany and France, were sent to the woods around Riga. Among them was the ’22nd Osttransport,’ with 791 Jews from Berlin. They had been packed into regular passenger trains—not into cattle cars as was usual for Jewish transports. It must have given the prisoners a false sense of security and hidden from them that the Nazi authorities intended an especially gruesome end for them: mass execution. Before arriving in the Riga ghetto, the train was diverted to a village named Salaspils. There, at the ramp, the transport was divided: fifty young men were sent to work in a sugar factory in Mitau, and a few more were detailed to help build the concentration camp Kaiserwald. (One, at most two, members of the work details survived.) All the others—more than 700 people—were taken into the woods to the killing grounds, where mass graves had been dug by Russian POWs.”[131]

The last known direct transport from the west to Riga was the abovementioned transport from Theresienstadt on 20 August 1942. The 22nd Osttransport is stated to have departed from Berlin on 26 October 1942 (the number of deportees is alternatively given as 801 or 808).[132] In preserved German documents no destination is listed for this transport.[133] The next Osttransport from Berlin, with 1,021 deportees, departed for Auschwitz on 24 November 1942. If we take a look at the succeeding Berlin transports things get even more curious. Raul Hilberg notes that

“the transport of November 29, 1942, with 1,001 Jews, is listed as destined either for Auschwitz or Riga, and the transport of December 14, 1942, with 811 deportees is allocated to Riga. The prosecutor could not find survivors of either transport, and proof of their arrival in Riga is lacking. It is likely that both were directed to Auschwitz […].”[134]

The court document which Hilberg refers to[135]—which the author has not had the opportunity to access—apparently refers to other transport lists than those kept at NARA, because the latter lists three Osttransporte from Berlin departing in November and December 1942: One transport on 20 November with 1,021 deportees, a second on 14 December with 813 deportees and a third on 15 December with 1,061 deportees. For none of these transports is a destination listed. Danuta Czech in her Kalendarium lists no transports from Berlin as having arrived in Auschwitz during December or the last days of November; the next listed arrival from Berlin, with 1,000 deportees (no documentary source is stated for this entry), is on 13 January 1943[136]—this is most likely identical with the Osttransport listed in the NARA transport lists as departing Berlin on January 12 (here the number of deportees is given as 1,190).

Here we may ask in passing whether being sent to Salaspils more or less meant certain death for Jewish prisoners, as implied by many exterminationist historians. Jack Ratz, who was briefly sent to Salaspils after the liquidation of the labor camp Lenta in 1944, states that the camp commandant of Lenta, the SS man Fritz Scherwitz—who in secrecy was a Jew who had been adopted by a German soldier during World War I and for that reason took care to treat the Jewish inmates well—”had been ordered to send all the Jews to Germany” at the time of the liquidation but instead sent the Jews in the Lenta camp to Salaspils: “He felt that we had a chance to survive at Salaspils, although it was a notorious death camp”.[137] The contradiction is dumbfounding. Obviously Scherwitz knew that Salaspils was not a very dangerous place, and definitely not a “death camp”

As for Friedrich Jeckeln’s claim that French and Dutch Jews had arrived in Salaspils we find a glimpse of a possible confirmation of it in an article which the Soviet journalist B. Brodovsky wrote after having visited a childrens’ home in the Riga suburb of Bolduri (or Bulduri) some time in late 1944:[138]

“Living at the home at the present time are boys and girls who were rescued from Salaspils, a German death factory near Riga. Although there are more than 400 children in the home, a death-like silence reigns in the rooms, for the children are still under the terrifying impression of their recent ordeals. […]

In Salaspils there were special barracks for children with cots in four tiers. However, there were so many children that some of them had to sleep on the floor. The toilets were in the courtyard, but the children were expected to observe the same regulations regarding their use as the adults. Living in the same barracks were Alexei, Lenya, Valya and Kilya Kondratenko. Kilya, the youngest, was only a year and eight months. […]

The Germans had a reason for organizing children’s barracks in Salaspils. They needed a factory for the extraction of blood and the children were good raw material. The camp administration had an agreement with the German Red Cross to supply them with blood, and they did, by the bucketful, which was sent in ampules to the hospitals every day. This was an establishment of which the fascist vampires might well be proud; two hundred liters of children’s blood a day.

We talked to young victims from Leningrad, Vitebsk, Poltava and Amsterdam. We even saw two little girls from Paris. From these children we learned of the inhuman practices of this factory.”

The journalist then goes on to describe how he was shown “the findings of medical investigations of children in the Bolduri childrens’ home and also quotes briefly from the files on five of the children, all of them apparently evacuees from Belarus: Natasha Panfilova (12 yrs), Pavel Levchenko (12 yrs), Grigori Senkevich (7 yrs), Dmitri Sakson (8 yrs) and Anya Karamish (1 yrs 7 months).[139] It is unfortunate that Brodovsky does not mention the name of any of the Dutch or French children, but his account indicates that their names and other personal data were recorded by Soviet investigators, and that they thus may still be retrievable from archived documents.

No documentary evidence confirming the allegation that child prisoners served as involuntary blood donors has ever been found, and the claims presented in the Soviet press that 7,000 children perished at Salaspils are viewed as absurd by contemporary Latvian historians.[140] This of course does not preclude that child inmates liberated from the camp were placed in Bolduri and examined by Soviet physicians.