Memories of a Thessalonian Jewess

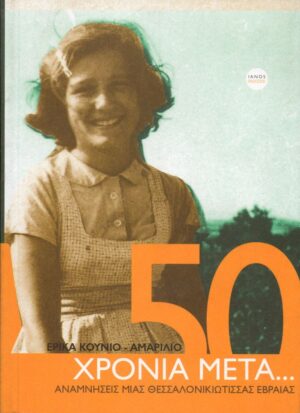

Erika Kounio-Amarilio, 50 χρόνια μετά: Αναμνήσεις μιας Θεσσαλονικιώτισσας εβραίας (50 khronia meta: Anamneseis mias Thessalonikiotissas Hebraias, translating to 50 Years Later: Memories of a Thessalonian Jewess), Parateretes, Thessaloniki 1996/Ianos, Thessaloniki, 2006.

Erika Kounio was the editor of the book Oral Testimonies of the Jews from Thessaloniki about the Holocaust examined in an earlier article.[1] As she was also a Holocaust survivor, we will now have a look at her own memoir, 50 Years Later: Memories of a Thessalonian Jewess.

Kounio was deported along with her family to Birkenau on March 20, 1943 at age 15. Since she and her parents could speak German, they worked as interpreters. Later, she was transferred to Auschwitz where she worked as a secretary, filling in the death registers. On January 18, 1945, when the camp was evacuated, she was sent on a “death march” to Ravensbrück, and later from there to an unknown destination. Along with other prisoners, they managed to escape and hid in a deserted barn. The Russians found them a few days later, and she eventually returned to Greece.

Kounio was deported along with her family to Birkenau on March 20, 1943 at age 15. Since she and her parents could speak German, they worked as interpreters. Later, she was transferred to Auschwitz where she worked as a secretary, filling in the death registers. On January 18, 1945, when the camp was evacuated, she was sent on a “death march” to Ravensbrück, and later from there to an unknown destination. Along with other prisoners, they managed to escape and hid in a deserted barn. The Russians found them a few days later, and she eventually returned to Greece.

Despite working as a secretary, she had a really hard time at Auschwitz. But what exactly does she tell us regarding the extermination claims?

Radio Propaganda

The first interesting incident she reports is about her grandfather, before the deportation. Her grandparents lived in the Sudetenland. In 1939, they fled the country to escape the Germans, and came to Greece. Here is what happened one night:

“It must have been November, always in 1942, when in the evening – as every evening – we heard on the radio the BBC news. Everything was closed in the room, and the front door was locked. At one point, we heard the speaker saying indifferently that two Polish Jews had come to the radio station that morning who had escaped from a ‘camp’ named ‘Lublin.’ There – the speaker continued just as indifferently – they were mass killing the Jews. With no further comment, he continued with the rest of the news. I will never forget the face of my grandpa. He rose all red with eyes popped out and turned off the radio. He turned to my parents and said, ‘This is English propaganda.’ He had arrived here three years earlier, a hunted refugee, to find shelter in Greece, at the house of his daughter, and yet he still believed that the Germans were a superior people! And all that from London was propaganda!” (p. 64)

Perhaps her grandpa knew better?

Selection Time

After arriving at Birkenau, the usual procedure followed. Children, sick and the old were loaded onto waiting trucks:

“The people kept going onto the trucks, which left as soon as they were full. Where did they go? Unknown!” (p. 87)

When they arrived later at their block, they asked the other prisoners about this. Once again they received the all too common reply:

“For a minute there was dead silence; some started going away from us, and two or three told us the unbelievable, the unheard of: ‘They are no more; they burned them all; they turned into smoke coming out of the chimneys…’ Crazy, I thought, totally crazy, they’ve lost it, they don’t know what they’re saying.” (p. 91)

But as usual, it didn’t take too long for her to believe it as well.

Special Treatment

Kounio gives some interesting information regarding those that were supposed to be sent to the gas chambers:

“Near the ‘office’ there was Block 25. It was also a barracks where they collected all those women that had gone through a ‘selection.’ Many times they were kept there for as much as three or four days, until they were led to the gas chamber. […] The lists with the names of those that had gone to Block 25 had to be filled, the names had to be written quickly and correctly. […] Here’s another sample of the German meticulousness. Compose the lists with the names of ‘candidates to die,’ with their names written correctly, and insert them into their files.” (p. 107)

She claims that this was done on every selection, whether it was a mass selection among new arrivals, or one of those carried out daily before and after work. A few pages later she adds:

“The names of all those that had gone through a selection at the Birkenau and Auschwitz camps were recorded on lists which were sent at the central offices of the P. A. [Politische Abteilung, the camp’s police section] where we worked, for registration. On each one of those lists there were also written the discreet letters S.B., which means Sonder Behandlung, that is ‘special treatment.’ Those people who were on the S.B. lists were ‘specially treated’, that is killed with gas.” (p. 114)

But according to the orthodox narrative, those arriving at the camp who were allegedly selected for the gas chambers were not registered anywhere. If people who had been selected were “meticulously” registered, that can only mean they were not about to enter a gas chamber. As for special treatment, and the word special in general, it appears on many documents that have nothing to do with killings.[2] Kounio also writes:

“Every time a child was born, it would receive its serial number and the lists of newborns would arrive at our offices for the archives.” (p. 139)

It could hardly be worse! Registration of newborns? How can this be reconciled with the extermination of the unfit?

The Extermination

So, we arrive at the main point: Extermination with poison gas. But on this critical issue, Kounio has absolutely nothing specific to say. Nothing on the gas chambers, nothing on the crematories. Number, location, operation, anything at all, are totally absent. There are only vague descriptions like this:

“They lived for some months there, when one day we learned that the Gypsy Camp had been emptied. They sent them all to the gas chambers.” (p. 139)

Or this:

“Almost every day there were new arrivals, thousands. The percentage of those who entered the camp was about the same on every transport, about 200 to 500 persons at most, men and women together. The rest of the thousands went directly to the gas chambers.” (p. 141)

On the same page, regarding the deportation of the Hungarian Jews in spring/summer 1944, we read:

“Thousands, many thousands arrive daily at the ‘ramp’ of Birkenau. From many cars they do not disembark at once, they wait endless hours inside for their turn. A ‘road’ was created leading from the ramp directly to the gas chambers, without passing with the trucks through the camp. The crematories are working non-stop and cannot keep up. They opened large pits; they throw wood, corpses, and set fires. They burn them there, because the crematories are not enough.”

Not only the description is vague but the story about a newly built road right from the railway ramp to the gas chambers makes no sense. In fact, the railway line itself was extended in early 1944 to enter the camp alongside the camp’s main road, there forming a new ramp. It ended right next to Crematoria II and III at the western end of the main road. It’s clear that Kounio is repeating mere hearsay. She admits it herself:

“Another time, a woman brought us the news that infants, babies up to two or three years old, were thrown alive into the flames by the SS, into the pits they had prepared.” (p. 142)

Needless to say, she believed that as well.

Summary

Kounio’s memoir was first published in 1996. As she states, she decided to write 50 years after the events because more and more people were disputing the Holocaust, and there had to be a way to refute them. But if someone actually reads her book, the conclusion he will draw is that perhaps it would have been better if she had kept silent. Her own experiences do not confirm the orthodox storyline. It should be added that both she and her mother got seriously sick at the camp (her mother contracted typhus), and yet they were sent to the hospital, not the gas chamber, and they were given all the care needed to recover. Regarding her extermination claims, she does not offer any reliable information. Hence, we have yet another credible witness whose fear prevailed over reason.

Let’s close with this illuminating incident:

“A kid in elementary school who visited the exhibition organized by our community in 1993 with documents, photos and various objects, all about the Holocaust, asked in his father full puzzlement: Were the Germans so dumb and kept all this evidence?” (pp. 89f.)

Notes

| [1] | See my review “Some Testimonies from Thessaloniki,” Inconvenient History, Vol. 9, No. 4; https://codoh.com/library/document/some-testimonies-from-thessaloniki/. |

| [2] | See Carlo Mattogno, Special Treatment in Auschwitz: Origin and Meaning of a Term, 2nd ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield 2016; and idem, Healthcare in Auschwitz: Medical Care and Special Treatment of Registered Inmates, ibid. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, Vol. 10, No. 1 (winter 2018)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a