My Campaign for Justice for John Demjanjuk

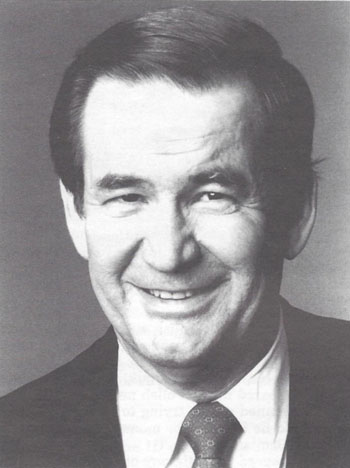

John Demjanjuk’s vindication – culminating in his recent reunion with his family in the United States – has special meaning for Jerome Brentar. For more than a decade, this deeply religious man of Croatian ancestry and anti-Communist conviction has devoted countless hours of his own time and considerable money from his own pocket to help defend the Ukrainian-American auto worker.

This was not the first such case in which Brentar had played an important role. In the earlier case of Frank Walus, Brentar dug up evidence that proved to be of crucial importance in exonerating the Polish-born American.

It was only after a protracted and devastating legal ordeal that Walus, who has gratefully called Brentar “my savior,” was able to establish that he was not a Gestapo murderer of Jews in wartime Poland, as Simon Wiesenthal, the United States government, eleven Jewish “eyewitnesses,” and several newspapers had insisted, but instead had spent the war years as a quiet teenage farm laborer in Germany. (For more on this case, see the Summer 1992 Journal, pp. 186–187.)

Brentar’s dismissal in early September 1988 as national co-chairman of a George Bush presidential campaign organization – after a Jewish weekly paper focused attention on his efforts on behalf of Demjanjuk – made headlines in newspapers around the country, and brought Brentar’s face to national television news broadcasts.

Explained a Bush campaign aide: “We became aware of his [Brentar’s] affiliation with the group that supports the defense of John Demjanjuk, and that position is at fundamental odds with the Vice President [Bush] and this campaign. And we took the action based on learning about that today. … We told him [Brentar] that his advocacy on this issue puts him at a fundamental disagreement with the campaign and the Vice President.”

Commenting on his dismissal, Brentar said: “It’s part of a dirty smear campaign that started because I said Demjanjuk is innocent. For that, I’m called a neo-Nazi and an anti-Semitic revisionist.” Brentar also noted: “I could have been an atheist. I could have been a polygamist. I could have been anything else, and questions wouldn’t have been asked. And now because I helped a poor victim, I’m everything under the sun.” (New York Times, Sept. 9, 1988.)

A mark of the sorry moral level to which our country has fallen is not only the shameful role of the US federal government in the persecution of John Demjanjuk, but that an American vice president could see fit to order the removal of a man as decent and upright as Brentar from a campaign committee because of his selfless work on behalf of an American citizen he passionately believes to be innocent of monstrous crimes, in a country where people are supposedly presumed innocent until proven otherwise.

On September 14, 1988, not long after his dismissal from the Bush campaign, Brentar appeared on the CNN cable television program “Crossfire,” along with New York Congressman Stephen Solarz and co-hosts Tom Braden and Pat Buchanan. On a nationally-televised broadcast, apparently for the first time ever, the great taboo of Holocaust revisionism was breached.

Although Brentar was reluctant to get into the Holocaust issue itself, the program’s “liberal” fossil, Tom Braden, gave further evidence of his calcified mindset by vigorously claiming that he personally saw gas chamber victims at Buchenwald at the end of the war. Co-host Pat Buchanan, a savvy and courageous writer and probably the most prominent national defender of Demjanjuk, thereupon cut in and pointed out that no serious historian makes that claim anymore.

Braden responded with sheepish silence.

Stephen Solarz, a Congressman from Brooklyn who boasted in 1981 that he had become a member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee in order, as he put it, to “deliver for Israel,” lost control of himself. He charged that Brentar’s greatest sin was not that he defended Demjanjuk, but that he had doubts about the Holocaust story.

Although Brentar explained that he preferred not to get into the issue, Solarz insisted on a statement. “Did Jews die in gas chambers at Auschwitz? Were six million Jews killed?,” he demanded. Finally, Brentar simply said that although he is not a scholar of the Holocaust, there are certainly absurdities and contradictions in the Holocaust story. Brentar specifically mentioned the once seriously made allegation that masses of Jews were put to death at Treblinka in huge steam chambers, and he mentioned the now discredited story of mass killing by electricity.

Brentar’s calm and factual remarks only further enraged Solarz. After another outburst from the ultra-Zionist politician, Buchanan shot back, “don’t be a complete phony,” a remark that so stunned the normally loquacious lawmaker that he was momentarily struck speechless.

Over the years, Jerry Brentar has endured a barrage of outrageous attacks against his character, including loud criticism for speaking at IHR conferences. But long after such mean-spirited carping is forgotten, this noble man will be remembered as the person without whose intrepid and selfless help John Demjanjuk almost certainly would have been deported to the Soviet Union and executed for crimes he did not commit.

– M. W.

Jerome A. Brentar was born in 1922 in northern Ohio, the son of immigrants from Croatia. During the Second World War he served in Europe with the US Army's 93rd Armored Cavalry. From 1948 to 1950, he worked in postwar Europe as an eligibility/screening officer for the International Refugee Organization (IRO) of the United Nations. From 1954 to 1957 he worked in Europe for the Catholic Relief Service of the National Catholic Welfare Conference, a Roman Catholic refugee assistance agency. Besides English and Croatian, Brentar speaks German, Polish, Russian and Ukrainian. He studied at Michigan State University and at the University of Munich in Germany. Back in Ohio, he founded and for many years directed Europa Travel Service, a travel agency in Cleveland.

This essay is adapted from his address at the Eleventh IHR Conference, October 1992. (Brentar's presentations at the 1989 and 1992 IHR conferences are available on both audio and video cassette from the IHR.)

I appreciate this opportunity to address fellow Americans who share my concerns. I wish first to take this opportunity to thank the Institute for Historical Review for creating this citadel of free speech. I commend the IHR and its supporters for their tremendous job, under very trying circumstances, to protect this right of freedom of speech.

John Demjanjuk has been a victim of an unprecedented travesty of justice. The US Justice Department’s Office of Special Investigations, working with the Soviet government, and those who might be called “Holocaustians” have carried on a campaign to portray this innocent man as “Ivan the Terrible” of Treblinka.

For their part, the Soviets have always been concerned about the Ukrainians because of their efforts for independence from Russia. Accordingly, the Kremlin worked to instill in the Ukrainians, and in the other non-Russian peoples of the USSR, the fear that the long hand of the Soviet secret police can track down any of them, anywhere in the world. This is why John Demjanjuk was targeted.

This Soviet effort received cooperation from the federal government’s Office of Special Investigations, the OSI, and the pro-Israel lobby. The people in the OSI are interested, first of all, in holding onto their lucrative jobs, while the “Holocaustians” want to keep alive the multi-million dollar Holocaust industry.

Essential to this campaign has been the sensationalism of the “hunts” and trials of alleged “Nazi war criminals” such as Frank Walus, Andrija Artukovic, Tscherim Soobzokov and, of course, John Demjanjuk. Newspapers join in this because they sell best with sensationalized atrocity stories.

Wartime Beginnings

In a way, my involvement with the Demjanjuk case began during World War II, while I was serving as an American soldier in Germany. During the final months of the war, masses of German soldiers came under our control as prisoners of war. I was one of those who helped to process these prisoners, and I examined the documents of many of these men. This experience gave me a very vivid picture of what wartime German documents look like. And then, after the war – because I speak German and Slavic languages – I got a job with the International Refugee Organization working in Germany. At that time, there were millions of “displaced persons” in Germany. In that job, which gave me access to additional important information, I had to examine the documents of many of these refugees.

I first became aware of the federal government’s legal prosecution of John Demjanjuk in 1980, when I saw reprinted in Cleveland newspapers a facsimile of a supposed identity card proving that this was “Ivan the Terrible” of Treblinka. This in spite of the fact that this alleged “Trawniki” ID card, which was the key piece of documentary evidence against Demjanjuk, does not mention Treblinka at all, but instead places him at Sobibor and at an agricultural estate in Poland.

A dramatic moment during the trial in Jerusalem of John Demjanjuk: Prosecution witness Elijahu Rosenberg angrily spurns the defendant's offered hand as Demjanjuk attorney Mark O'Conner looks on.

Along with this piece of evidence, the government produced five witnesses from Israel who testified that Demjanjuk was the notorious Ivan of Treblinka. As it happened, though, one of these witnesses, Elijahu Rosenberg, had told the Polish War Crimes Commission in 1945 that the man known as Ivan of Treblinka had been killed during an uprising at the camp in August 1943. Rosenberg repeated this claim in a statement given in December 1947 at the Jewish center in Vienna, declaring under oath that Ivan of Treblinka had been killed. Some years later, though, testifying against Demjanjuk in Cleveland in 1981, and again in Israel in 1987, Rosenberg changed his story. He admitted that, yes, he had stated that Ivan the Terrible was dead. At the trial in Israel, however, he said, pointing, “But he’s there. He’s alive. I’m seeing him there!” It was testimony like this that brought the sentence of death against this poor man.

Streibel’s Testimony

After seeing the ID card in the newspaper, I called Mr. Karl Streibel, who had been commandant of the Trawniki camp, where this document had supposedly been issued. Streibel told me:

Mr. Brentar, I told your people from Washington, who came to see me three years ago, that this is not an ID card from Trawniki. I told them that Trawniki was a training camp for those men who were chosen to work as guards for the Germans, and that this was a training camp not only for concentration camp guards. There were approximately five thousand men there, most of whom were then assigned to guard military installations, bridges, depots, motor pools, and so on. About three hundred of them were assigned to guard at camps such as Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor.

Mr. Streibel went on to tell me:

Mr. Brentar, the attorneys from the OSI were here, and I told them to bring me the original ID card. I wanted to see the original because I would absolutely never sign any document without putting the date and place of issue before my signature.

The OSI was very much concerned that Demjanjuk’s defense attorneys would try to meet and talk with Mr. Streibel. And indeed a meeting was arranged in Hamburg with Streibel and the defense attorneys, Mr. John Martin and Mr. Spiros Gonakis. But even though a date and a time in the late afternoon had been set for the meeting, as John Martin later told me, he received a phone call, allegedly from a friend of Mr. Streibel, informing him that he was not interested in meeting with the gentlemen from America after all. As it turned out, Streibel received a similar telephone call, allegedly from the defense attorneys, telling him that they were not interested in seeing him. This clearly seems to be another example of the dirty tricks engaged in by the OSI in its campaign to prosecute and persecute this man, and bring him to KGB-style justice.

Additional Testimony

As you can appreciate, I quickly became very suspicious of the charges against Demjanjuk. I then began a years-long search for evidence, tracing the route followed by the OSI in its search for evidence against this man. In Germany, I met with the wartime commandant of the Treblinka camp, Kurt Franz, who was then serving a sentence in a prison near Düsseldorf. During our meeting, Franz told me: “Mr. Brentar, several years ago six of your people were here, and I told them that this man [Demjanjuk] is not the Ivan of Treblinka. The Ivan of Treblinka was much older, had dark hair, and was taller. He had a stoop because he was so tall. So why do you come here again to ask me the same questions?” I replied: “Mr. Franz, I am not from Washington. I’m from Cleveland, Ohio, and I’m trying to help this man.”

I want to mention here that the Institute for Historical Review, and its friends and associates, have really helped me to establish contacts with people who proved instrumental in helping put together a thorough and truthful picture, of what happened – and still is happening – to John Demjanjuk.

Well, as I continued my investigation, I arranged to meet with every one of the people whom the OSI had visited earlier. What I discovered is that the OSI’s case against John Demjanjuk was built on lies, exaggerations, distortions, fabrications, innuendos, and dirty tricks.

Obstacles in Israel

Visiting Israel, I arranged to go with a Jewish friend to meet with Menachem Russek, chief of the agency that is the Israeli counterpart of the OSI in the United States. “Mr. Russek, don’t be a fool,” I said to him. “You’re being misled by the OSI. This is an innocent man.” And even though I had brought along evidence to prove what I was saying, well, he couldn’t care less, because he was every bit as eager to prosecute and persecute John Demjanjuk as was Neal Sher and his OSI entourage.

I asked Mr. Russek if I could speak with the three main witnesses against Demjanjuk: Pinchas Epstein, Elijahu Rosenberg and Sonia Lewkowicz. I particularly wanted to meet with Rosenberg, to question him about the discrepancies in his sworn statements. “I’m here to give you everything I have – all the truth,” I told Russek. “Why don’t you let me meet with these people so I can question them?” Well, for obvious reasons, I was not permitted to meet with any of them.

Fedorenko’s Fate

John Demjanjuk was originally supposed to be deported to the Soviet Union where, as you know, the authorities make quick work of liquidating their “enemies.” That’s what happened to other “Nazi war criminals” from the United States, such as Karl Linnas and Fedor Fedorenko. While Fedorenko’s case was on appeal, OSI chief Neal Sher met with the Ukrainian-born Fedorenko and told him: “Look, why don’t you go back to your homeland. You’ve already been back several times.” (That was true: he had a wife and a family there, and had returned several times since the war.) “This appeal will cost you a lot of money. Why don’t you go back and spend the rest of your life with your family there?”

That was a trick. No sooner had Fedorenko, the poor fellow, arrived there with thousands of dollars worth of Soviet rubles, which he had bought on the black market (getting a much better rate than he could have gotten in Russia), then he was arrested and, after a quick KGB trial, shot. I am convinced that Neal Sher had notified the Soviets of his arrival, to get rid of him and prevent him from testifying in the Demjanjuk case.

Villagers’ Testimony

In Poland I visited Treblinka and the nearby villages. In one such village I visited the house of Maria Dudek. When I showed her the photograph of John Demjanjuk, she said to me, in Polish: “I never saw this man before.” But when I asked her if she ever heard of “Ivan the Terrible,” she panicked and shut the door on me.

I found three other witnesses from that village, former inmates of Treblinka, who had seen “Ivan.” These three villagers were supposed to come to Cleveland to testify in court. But an OSI official named Michael Wolf telephoned the US Consulate in Warsaw and told officials there: “Don’t let the witnesses come. The hearing is over.” That was a lie; the hearing was still continuing. This was another of their many dirty tricks. They prevented these three witnesses from testifying on behalf of Demjanjuk.

Pinchas Epstein, a key prosecution witness in the Jerusalem trial of Demjanjuk, accuses the defendant of being the notorious Treblinka camp guard known as “Ivan the Terrible.” (Reuters/Bettmann photo)

Wolf also told the Polish authorities that I’m a neo-Nazi, an anti-Semite and a revisionist, and that I’m paying money to witnesses to lie to defend a Nazi murderer, John Demjanjuk. As a result, a long article appeared in the Polish newspaper Polityka that condemned me for trying to recruit witnesses who would lie in court for money as witnesses on behalf of Demjanjuk.

With regard to testimony of Maria Dudek, I’d like to mention an article from the Cleveland Plain Dealer (Sept. 13, 1992), headlined “Demjanjuk wasn’t Treblinka’s ‘monster,’ ex-captives insist,” which reports that an additional witness named Nina Shiyenko likewise confirmed that “Ivan of Treblinka” is not John Demjanjuk.

Such incidents tell just part of the story of what has happened to this poor man, John Demjanjuk. But there’s an old saying that I think applies in this case: “Every evil carries within itself the seed of its own destruction.” And that seed has begun to germinate.

Exonerating Evidence

As a result of all the exonerating evidence that I was able to provide to the defense, Demjanjuk was not deported to the Soviet Union, as was originally planned. Instead, OSI chief Sher panicked. He ran to Israel to tell the authorities there to work for Demjanjuk’s extradition to that country, because of the danger that the case was being lost in Cleveland. There’s too much evidence to show that Demjanjuk is innocent, he told them. As a result of his effort, Israel made an official request for his extradition.

According to the legal rules for extradition that were in effect at that time, it was not permissible to submit any further evidence on behalf of a defendant. So it was planned to present the additional evidence to the court in Jerusalem.

The OSI was incensed at my activity. They couldn’t understand how an insignificant travel agent could be so successful in finding such potent evidence against them – evidence proving that they were lying.

A Journalist’s Admission

Back in Cleveland, in 1984, I visited the office of the Plain Dealer, the city’s main newspaper, which was supposedly supporting Demjanjuk. Regrettably, though, they printed more negative than positive articles about him. A Plain Dealer reporter said to me: “Jerry, we’re not interested in his innocence. We’re only interested in his extradition.”

The Bush Campaign

I want to tell you a little more about how I was asked to resign from the Bush presidential campaign. Actually, I had never been active in Bush’s campaign, the Republican party, or even in politics. So I was very much surprised when I learned that I had been chosen to become co-chairman of the Bush campaign’s national ethnic coalition group. In Washington I was received by Mr. Bush, who congratulated me. When he asked me to support him, I told him that I would. My hope was that this might give me a further opportunity to help John Demjanjuk.

Unfortunately, in this God-blessed country of ours, it’s no longer what you know, but who you know, that counts. About a month after I was named, I received a phone call from an official of the Bush campaign, who told me: “Mr. Brentar, the Vice President is very much upset because we’ve been getting all kinds of calls telling us that you’re a neo-Nazi, that you’re an anti-Semitic revisionist, and that you are helping a convicted Nazi war criminal. Mr. Bush wants you to leave the ethnic coalition, and I calling to ask you to resign.” I replied by telling him: “My dear man, I am with the campaign by invitation. If you want me to resign, please send me this request in writing, and I’ll consider it.” Well, I never received it.

As a result of that, my name appeared in newspapers around the country, and I received phone calls from Argentina, Australia, and from people I had met and worked with years earlier in Germany, who asked me what was going on. “I don’t know myself,” I told them. “I’m just trying, as a true American, to help an innocent man, and instead I’m being lambasted as an anti-Semitic neo-Nazi revisionist.”

Pat Buchanan

Some good did come out of all this publicity, though. One day I got a call from a Mr. Matt Balic of New Jersey. Like me, he is of Croatian background. He told me that he he’d like to introduce me to Pat Buchanan. Balic told me that I have an important story to tell, and asked if I’d like to appear [on the television program] “Crossfire.” “Sure,” I replied. So that’s how I came to appear on “Crossfire.” I got to know Buchanan very well, and from that time on I sent him much information that he used in writing articles in defense of Demjanjuk.

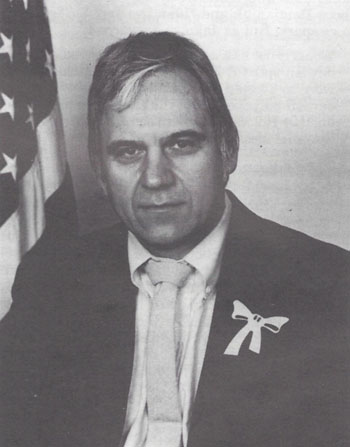

Congressman Traficant

A short time after that, Matt Balic arranged for me to meet Congressman James Traficant. Well, after I finished telling him the whole story, much as I’m telling it to you here, but in even more detail, Traficant said to me: “Jerry, I can’t believe this. Are you lying to me? Are you exaggerating?” And I said, “Why should I? I’m not paid. I’m doing this voluntarily because I am for truth and justice, and that’s the only way we’re going to have peace in this world, with justice.” Well, after that meeting this man really went to bat for me, and for Demjanjuk, going far beyond the call of duty.

Another “Ivan”

It was during its investigation of Fedorenko that the OSI had obtained copies of court transcripts of the Treblinka trials in the USSR that referred to the Ivan of Treblinka. These papers, which were not made available to the defense in Demjanjuk’s denaturalization hearings in Cleveland, include the testimony of 18 former Treblinka guards who confirmed that the “Ivan of Treblinka” was a man named Ivan Marchenko (or Marczenko). These documents had been in the hands of the OSI since 1978, so these US government officials knew very well that John Demjanjuk was not “Ivan the Terrible” of Treblinka.

In August 1991, Congressman Traficant was able – through the Freedom of Information Act – to obtain copies of these documents, which proved to be crucial in finally exonerating Demjanjuk. Traficant even arranged for John Demjanjuk’s son-in-law, Ed Nishnic, along with John Demjanjuk, Jr., to go to Poland and the Soviet Union in December 1991, as his aides, to obtain additional excuplatory evidence. During this visit, the two men met with Marchenko’s daughter.

“Political Suicide”

Until my meeting with Jim Traficant, we had had no luck at all with politicians. Earlier, John Demjanjuk, Jr., and I had visited Washington, DC, where we rapped on the doors of every Congressman and Senator to ask for help in the defense of an innocent man. The Representatives from the Cleveland area, Demjanjuk’s home, whom one might have expected to be most willing to help, wanted nothing whatsoever to do with the case. A few Congressmen were somewhat sympathetic, but they did nothing.

One Congressman, Dana Rohrabacher, who represents a district in southern California, explained frankly to me why he would not help: “Jerry, do you want me to commit political suicide?” Is this really the kind of country we now live in? Pat Buchanan really hit the nail on the head, I think, when he referred to the US Congress as “a parliament of whores” on “Israeli-occupied” capitol hill. Because of comments like that, Buchanan is, of course, near the top of the ADL’s enemies list.

I am not so far down on that list myself. I’m not trying to brag, but while I was in Israel attending the trial of Demjanjuk, the prosecutor took time to ask me to stand up and to identify myself as a defender of the convicted murderer. When I did, I was booed. My name also came up during the appeal hearing last year, when the charge was made that the defense case was suspect because it had to rely so much on help from a revisionist, an anti-Semite and a neo-Nazi – me, that is – in obtaining all this lying, crooked information and testimony.

“Big Business”

The people who work for the Office of Special Investigations claim to be motivated by concern for the memory of the dead. But I am sure that none of those people would lift a finger for anyone if the Holocaust was not so profitable and prestigious. There is truth to the saying, “There’s no business like Shoah business.”

This point was confirmed by Rabbi Immanuel Jakobovits, who is Chief Rabbi of Britain, and Lord in the British parliament. A front-page article in the Israeli newspaper Jerusalem Post (Nov. 26, 1987, p. 1) reports:

Despite widespread acceptance of the Holocaust as a tragedy unique in Jewish history, leading [Jewish] Torah scholars are “unanimous” in “denying the uniqueness of the Holocaust as an event any different … from any previous national catastrophe,” according to British Chief Rabbi Sir Immanuel Jakobovits.

The Holocaust, Jakobovits went on to say, has become “an entire industry, with handsome profits for writers, researchers, film-makers, monument builders, museum planners, and even politicians.” He added that some rabbis and theologians are “partners in this big business.”

Because it is considered the most important event in Jewish history, those who play up the Holocaust also find sensationalism necessary. Tales about Demjanjuk and “Ivan the Terrible” give the story spark. But as Jakobovits warned:

Would it not be a catastrophic perversion of the Jewish spirit if brooding over the Holocaust were to become a substantial element in the Jewish purpose, and if the anxiety to prevent another Holocaust were to be relied upon as an essential incentive for Jewish activity?

Ivan of Sobibor?

Now, as the story of Demjanjuk of Treblinka falls apart, efforts are being made to replace it with the story of Demjanjuk of Sobibor. Now it is claimed that “when Demjanjuk was an SS guard he took part in mass killings of Jewish citizens in Sobibor camp.” Well, that’s a lot of baloney because, as Karl Streibel explained to me: “Mr. Brentar, anybody who was [trained] in Trawniki had to have a Personalbogen.” This refers to a German personnel and identity record, which includes information about date and place of birth, a thumb print, and so forth.

Here, for example [holding up for everyone to see], is a facsimile copy of the Personalbogen identity record from Trawniki for Ivan Marchenko. If John Demjanjuk had actually been a guard at Sobibor, as some are now claiming, he would have received basic training at Trawniki, and his completed Personalbogen would therefore have been on file there as well. But there isn’t any.

False and Authentic Documents

As Mr. Streibel explained to me, the Soviets advanced so quickly on the Trawniki camp that those in charge there had no opportunity to destroy the camp’s files. The Soviets captured all those records, including the Personalbogen for Marchenko and others, as reproduced in facsimile here in this book [holding it up], which was written by a very good friend of mine, a German by the name of Dieter Lehner. I am sure that if a Personalbogen record for Demjanjuk had been on file at Trawniki, the Soviets would certainly have made it public.

In this book, which is entitled Du sollst nicht falsch Zeugnis geben (“Thou shall not bear false witness”), Lehner proves the phoniness of the widely-reproduced ID card that was a key piece of prosecution evidence against Demjanjuk. Lehner points out some 30 different errors in the supposed Demjanjuk ID card, and shows just what a genuine Trawniki ID card looks like. Lehner also cites, and in a few cases, reproduces in facsimile, authentic Personalbogen documents issued to other men who had been trained at Trawniki. He shows that every guard of this type who was assigned to a camp was first sent to Trawniki, where he received an Erkennungsmarke metal “dog tag,” but not a Trawniki ID card.

This [holding it up] is the ID card of Heinrich Schäfer, a German official in the camp administration who served as paymaster in Trawniki. It has the signature of the officer in charge, and includes Schäfer’s rank and the date and place on which the card was issued. Schäfer testified that the supposed Demjanjuk ID card was not issued in Trawniki.

German Subservience

Dr. Louis-Ferdinand Werner, a department chief of the Federal Criminal Office (Bundeskriminalamt) in Wiesbaden has similarly declared – as the German magazine Stern reports – that the infamous Demjanjuk ID card is not authentic, in any way or form.

It took quite a long time for the Germans to make such a statement. Some years ago, when I had just begun my own investigation into the Demjanjuk case, I visited the office of German Chancellor Helmut Kohl. I went with a friend who happens to be a priest in the parish in Ludwigshafen where Mr. Kohl is a parishioner. He had met with Mr. Kohl, who had said to him that, if there was anything he could do for him, please feel free to call upon him. So that’s why the priest and I took the liberty to go right to Kohl’s office in Bonn to ask for help in proving that the supposed Demjanjuk ID card is not authentic. During a meeting there with an aide or adjutant to Chancellor Kohl, I said that this supposed ID card is an insult to the German tradition of Ordnung (order) and Pünktlichkeit (precision). During the war, the Germans were proud of the care they took with everything, including their dress and their documents. Even during the war’s final months, everything had to be tip-top, and there was no place for such a sloppy document.

After we explained what we wanted, Chancellor Kohl’s adjutant said to us: “My dear friends, if you want any help from us [for this], you have to ask the Israelis for permission.” Just imagine! Well, I could go on and on to tell you about more of the many difficulties we’ve had in our efforts on behalf of Demjanjuk.

“Better to light a candle than to curse the darkness,” wrote Thomas Merton, the poet and Trappist monk. Some years ago, I choose to light a candle, and now it seems that the whole world is seeing the light of a great fire.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 13, no. 6 (November/December 1993), pp. 2-8

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: n/a