New Documents Raise New Doubts as to Simon Wiesenthal’s War Years

Historical News and Comment

The Institute for Historical Review has recently received copies of a transcript of a sworn interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, which was conducted in 1948. The copies, certified as “true and correct,” were obtained from the National Archives in Washington, D.C. To our knowledge this transcript has never been published or cited, in whole or in part. The interrogation contains statements by Simon Wiesenthal which may shed new light on his activities during the Second World War. A comparison of these statements with certain other sworn statements of Wiesenthal and with his account of the period 1939-1945 in his memoirs reveals a number of discrepancies which raise new doubts about Wiesenthal's credibility as to his activities during the war.

Simon Wiesenthal is the world's most famous “Nazi”-hunter. His claim to have brought Adolf Eichmann and more than a thousand other Third-Reich “war criminals” to justice has become the stuff of popular myth, familiar to tens of millions through his own writings as well as through fictionalized treatments of his career in bestselling thrillers and film and television hits. Wiesenthal's activities and example, more than those of any other man, have kept alive and institutionalized the international drive to track down and punish Germans and others alleged to have persecuted Jews during the Second World War. Few men of the postwar era have been honored as frequently as has Wiesenthal: a list of his decorations, medals, orders, and honorary degrees, including a special gold medal awarded by the U.S. Congress and presented him by a teary-eyed President Jimmy Carter, would fill two pages in this journal.

Fundamental to Simon Wiesenthal's moral authority as a “Nazi”-hunter, and serving also as the basis for his expertise on the crimes and criminals of Axis Europe, has been the story of his experiences at the hands of the Germans during the war. According to Wiesenthal's public account of his war years, as told in his The Murderers Among Us, and repeated in countless speeches and interviews, he endured almost continual suffering as a German

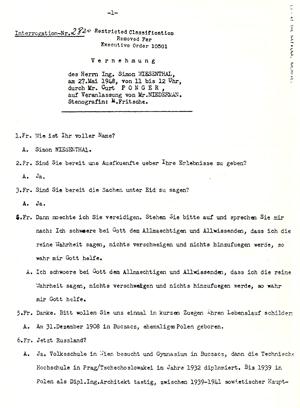

Page 1 of the transcript of Simon Wiesenthal's interrogation of May 27, 1948 (the heading is covered by the certification and seal of the National Archives; click to enlarge).

prisoner from July 1941 to May 1945, when he was liberated by American troops at Mauthausen. His time as a concentration camp inmate and “slave” laborer, his numerous narrow escapes from execution by his captors, and his witness to countless crimes and atrocities carried out against other Jews stamp him not merely as a survivor but as an accuser and avenger.

While doubts and even accusations have been raised in the past as to Wiesenthal's conduct during the war years, there has so far been no hard evidence made public in support of allegations, frequently raised, that Wiesenthal “collaborated” with the Germans. Nor, to our knowledge, has an exhaustive comparison of Wiesenthal's separate statements on his wartime experiences been undertaken.

New Evidence

Last spring IHR was able to obtain a certified copy of a transcript of an interrogation which took place on two consecutive days, May 27 and May 28, 1948.[1] The interrogator was Curt Ponger; the man Ponger was questioning, Simon Wiesenthal. The interrogation is described as having been brought about by (auf Veranlassung von) a Mr. Niederman, and was recorded stenographically by M. Fritsche. There is no indication of the place where the interrogation took place.

The transcript of that portion of the interrogation which took place on May 27, between 11 and 12 o'clock, runs to nine-and-a-half, double-spaced, typewritten, 81/2 x 11-inch pages. That of the following day, which was conducted between 11:30 and 12 o'clock (both times are presumably A.M., although this is not explicitly stated) covers nearer seven pages identical in size and format to the transcript of the first day's interrogation.

The May 27 transcript consists of twenty-eight questions and answers, that of May 28, twenty questions and answers. Answer No. 4 of the first day's interrogation is this statement by Simon Wiesenthal: “I swear by the Almighty and All-knowing God that I will say the absolute truth, conceal nothing and add nothing, so help me God”. (“Ich schwoere bei Gott dem Allmaechtigen und Allwissenden, dass ich die reine Wahrheit sagen, nichts verschweigen und nichts hinzufuegen werde, so wahr mir Gott helfe”).

Discrepancies

Among the sworn statements made by Simon Wiesenthal during this investigation are:

- that he was employed as a “Soviet chief engineer in Lvov [in German: Lemberg; in Polish: Lwow; in Ukrainian: Lviv] and Odessa” during the Soviet occupation of September 1939-June 1941;

- that he served as first a lieutenant and then a major in a Soviet partisan unit following his escape from German custody in October 1943;

- that he was about to be executed by the Germans as a partisan leader but was able to save his life by joining a group of Jews in German custody.

These sworn statements conflict with Simon Wiesenthal's account of his wartime years presented in The Murderers Among Us, his published memoirs, and with certain other sworn statements Wiesenthal has made regarding his war years. The above discrepancies, and a number of others evident when Wiesenthal's several accounts of his activities between September 1939 and May 1945 are compared, raise grave doubts as to the “Nazi”-hunter's credibility, and prompt a further question: What did Simon Wiesenthal actually do during the Second World War?

Three Stories Compared

In the following pages we have attempted a preliminary comparison of three different reports, each of which is an authoritative statement by Simon Wiesenthal. The reports are:

- the 1948 interrogation of Wiesenthal described above;

- a sworn statement which Wiesenthal submitted to the West German government when applying for reparations in 1954;[2]

- and the account of his wartime years which appears in The Murderers Among Us: The Simon Wiesenthal Memoirs, published in English in 1967.[3]

It should be stated at the outset that the aim in comparing these statements is not to attempt to impeach Wiesenthal's credibility by fastening on unimportant differences in detail, or by stressing omissions which may be understandable in view of the differing length and purpose of these documents. Nor is it implied that any of Simon Wiesenthal's statements, even when corresponding in the several documents, is to be taken at face value.

The Period September 1939-June 1941

During this period Simon Wiesenthal claims to have been a resident of Lvov, the metropolis of Galicia, which had been part of post-World-War-I Poland until, in consequence of the partition of Poland agreed on by Germany and the USSR in August 1939, it was occupied by the Soviets the following month.

According to The Murderers Among Us, Wiesenthal, as a “bourgeois” Jew (with his own architectural practice), ran the danger of being arrested by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police. We learn that both his stepfather and his stepbrother were arrested: the stepfather later died in jail and the stepbrother was eventually shot by the Soviets. The account of Wiesenthal's time under Soviet rule continues:

The Russians issued many “bourgeois” Jews so-called Paragraph 11 passports, which made them underprivileged, second-class citizens, not permitted to live in larger cities or within a hundred kilometers of any border. They lost good jobs and had their bank accounts confiscated. Proving himself a resourceful man under pressure, Wiesenthal bribed an NKVD commissar and obtained regular passports for himself, his wife, and his mother. A few months later, all Jews with “Paragraph 11” passports were deported to Siberia, where many died. The Wiesenthals managed to stay in Lwow, but Wiesenthal's days as an independent architect were over. He was glad to find a badly paid job as a mechanic in a factory that produced bedsprings.[4]

Wiesenthal gives a rather different statement as to his position under the Soviet regime in his 1948 interrogation. There he sums up his activities during the Soviet occupation in these words: “… between 1939-1941 Soviet chief engineer working in Lvov and Odessa” (“… zwischen 1939-1941 sowjetischer Hauptingenieur in Lemberg und Odessa”).[5]

These two contrasting statements suggest several questions. Is the evident discrepancy to be accounted for by Wiesenthal's desire to present himself in his memoirs, published during the “Cold War,” as primarily a victim of the Soviet regime, who narrowly escaped the fate of his stepfamily? Has he lied about athe badly paid job as a mechanic in a factory that produced bedsprings”? If it is true that Wiesenthal avoided deportation to Siberia for himself, his wife, and his mother by bribing an NKVD commissar, how much more might this “bourgeois” Jew have had to pay to obtain a position as a “Soviet chief engineer”? Or, finally, are we to understand that Wiesenthal's “collaboration” with the Soviet invaders was occasioned by a mutual sympathy between the Jewish “bourgeois” and the Communist invaders?

Escape from Lvov to the Partisans (?), October 1943

On June 22, 1941 the Germans and their allies invaded the Soviet Union; eight days later the first Germans entered Lvov. Just before they left, the Soviet authorities had massacred several thousand political opponents in the city's prisons. Most of the victims were Ukrainian nationalists, and the discovery of the slaughter unleashed a pogrom of epic proportions against the Jews of Lvov, who were hated by many of the city's Poles and Ukrainians for their Soviet sympathies and for their enthusiastic cooperation with the NKVD.[6]

Simon Wiesenthal came into the hands of the Germans in early July 1941, by his telling. The three statements compared in this article mention at least two different arrests, one by Ukrainian auxiliary police, after which Wiesenthal claims to have narrowly

escaped death; the other by soldiers of the Wehrmacht, who rounded up Wiesenthal and other Jews for hard labor at the railway yard. Here is not the place to analyze the conflicting accounts or to evaluate their credibility; nor to examine in depth Wiesenthal's stories as to his activities from July 1941 to October 1943, during which time he claims to have worked, first as a sign-painter, then as a draftsman, at the Ostbahn Ausbesserungswerk (Eastern Railroad Repair Works – OAW). For the purposes of this study it is enough to state that in his memoirs, Wiesenthal claims to have been in close co-operation with the Polish underground while at the OAW, and to have supplied them with detailed maps showing the vulnerable points of the Lvov railway junction.[7] He further alleges that he became so friendly with a sympathetic National Socialist superior, Oberinspektor Adolf Kohlrautz, that Kohlrautz permitted Wiesenthal to conceal two pistols in his (Kohlrautz's) desk.[8]

According to the shortest account of his escape and recapture, Wiesenthal's 1954 sworn application for reparations:

On October 17, 1943, immediately before the imminent liquidation of the Lvov camp, I fled from the camp and hid myself in a barn at acquaintances in the vicinity of Lvov. On January 13, 1944, on the occasion of a close search of this locality by the SD and Gestapo, I was discovered and committed to the Lacki Gestapo prison in Lvov.

(Am 17. Oktober 1943, unmittelbar vor der bevorstehenden Liquidierung des Lagers Lemberg flüchtete ich vom Lager und hielt mich in einer Scheune bei Bekannten in der Nähe von Lemberg versteckt. Am 13. Jänner 1944 anläßlich der Durchkämmung dieser Ortschaft durch SD und Gestapo wurde ich entdeckt und in das Gestapogefängnis Lacki in Lemberg eingeliefert.)[9]

That there is little chance of a casual mistake in the dates is shown by an affidavit which immediately follows the reparations application:

I hereby affirm in lieu of oath that I was interned in the Lvov forced labor camp from October 20, 1941 until my escape on October 17, 1943.

I further affirm that – after I was caught – I was in custody on January 13, 1944 until March 19, 1944 in the Gestapo prison in Lvov on Lacki Street.

(Ich versichere hiermit an Eides statt, daß ich – im Zwangsarbeitslager Lemberg vom 20. Oktober 1941 bis zu meiner Flucht am 17. Oktober 1943 inhaftiert war.

Weiters versichere ich, daß ich – nachdem ich aufgegriffen wurde – am 13. Jänner 1944 bis zum 19. März 1944 im Gestapogefängnis in Lemberg auf der Lacki-Straße in Haft war.)[10]

In each of the other two Wiesenthal statements under analysis, the “Nazi”-hunter claims to have escaped from German custody in Lvov on October 2, 1943. The date of his recapture is given in both these statements as June 13, 1944, exactly five months later than the date claimed in Wiesenthal's reparations application. Other than this agreement as to dates, Wiesenthal's 1948 interrogation and his memoirs differ in virtually every particular.

According to Wiesenthal's memoirs, in late September 1943 Wiesenthal and the other Jews working at the OAW were ordered to be sent under guard nightly to the Lvov (Lemberg) concentration camp. Sensing his impending doom, Wiesenthal prepared his escape. The obliging Kohlrautz, “who often permitted him to go to town to buy drafting supplies,” arranged for Wiesenthal to be accompanied by a “stupid-looking Ukrainian” policeman on a shopping expedition with Arthur Scheiman, another Jewish inmate. Naturally Kohlrautz permitted Wiesenthal to retrieve the two pistols he had hidden in the “good Nazi”'s desk.

After giving their escort the slip, Wiesenthal and Scheiman repaired to the Lvov apartment of a friend in the “Polish underground” (precisely which political affiliation is left unstated). After some days of concealment there and in Scheiman's house in the country, Wiesenthal and Scheiman found shelter in an apartment of other “friends,” where the two hid out under the floorboards until their recapture. Wiesenthal possessed not only arms but a diary and “a list of SS guards and their crimes that he'd compiled, believing that one day it might be useful.” On the evening of June 13, 1944 Wiesenthal was discovered under the floor, in possession of his pistol, diary, and list of SS men by two Polish plainclothes detectives and an SS man. Thus Wiesenthal's story as presented in The Murderers Among Us.[11]

On May 27, 1948 Wiesenthal told Curt Ponger under sworn oath that: “On October 2, 1943 [having] fled from Janovska [or Lemberg] concentration camp; I [joined?] a partisan group which operated in the Tarnopol-Kamenopodolsk area” (“Am 2. Oktober 1943 vom K.L. Janovska gefluechtet, habe ich mich an eine Partisanengruppe, welche in den Raum Tarnopol-Kamenopodolsk operiert hat”).[12]

During the next day's interrogation session, Wiesenthal went into much more detail. Aside from facing Ukrainian police formations and the Ukrainian-manned SS “Galicia” division, Wiesenthal's unit fought mostly against partisans from the UPA, or Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the military arm of the Ukrainian nationalist movement. According to Wiesenthal, as the Germans fell back and the front moved nearer at the start of 1944, the situation in his sector grew so chaotic that Soviet aircraft sometimes bombed his unit by mistake. With four or five different partisan groups at large in the same territory, “In January 1944 there was such confusion that one didn't know who was for him and who was against him. Whoever so much as stuck his head out of the woods would be shot at” (“Es war im Januar 1944 so ein Durcheinander, dass man nicht wusste, wer mit wem und wer gegen wen war. Wer nur seinen Kopf aus dem Wald streckte, auf den wurde geschossen”).[13]

After informing his interrogator that his partisan unit paid local farmers in dollars for provisions, Wiesenthal was asked: “Where did you get the dollars?” (“Woher bekamen Sie die Dollar?”). He answered as follows:

The Russian partisans had dollars, usually 100-dollar bills. We buried at least 70-80 thousand dollars. In any event the Russian liaison man with us always had enough dollars available… (Die russischen Partisanen haben Dollar gehabt, meistenteils 100-Dollarstuecke. Wir haben mindestens 70-80 Tausend Dollarnoten vergraben. Jedenfalls der russische Verbindungsmann, der mit uns war, hat immer genug Dollar zur Verfuegung gehabt… )[14]

Asked about the rank he held, Wiesenthal answered this way:

I had a high rank, I was immediately made a lieutenant on the basis of my intellect, then was promoted to major, and finally the commander said “If you come through this alive, then you're a lieutenant colonel.” I helped very much in building bunkers and fortification lines. We had fabulous bunker constructions. My rank was not so much as a strategic expert as a technical expert.

(Ich hatte einen hohen Rang. Ich kam direkt dorthin auf Grund des Intelligenzgrades als Leutnant, dann wurde ich zum Major befoerdert und zum Schluss sagte der Kommandierende, “wenn du die Sache ueberlebst, dann bist du Ober[st]leutnant.” Ich habe sehr viel mitgeholfen beim Bau der Bunker und Befestigungslinien. Wir haben grossartige Bunkerkonstruktionen gehabt. Mein Grad war nicht soviel als strategischer Fachmann wie als technischer Fachmann.)[15]

Although Wiesenthal never states explicitly the afflliation of his partisan unit, it seems clear from his remarks that it was part of the Armia Ludowa (People's Army), the Soviet-organized and -manned “Polish” guerrilla force. After his unit was surrounded in February, and forced to split up and escape through the German lines, Wiesenthal describes being hidden by friends in Lvov as follows:

We knew addresses, KIGNI – – – was the liaison man between AK and us. The sharp differences between AK and AL didn't exist yet. AK was nationalist and antisemitic and AL was not antisemitic. AK thus took in Jews in Lemberg, since the pressure of the Germans in Lvov was much stronger than in any other district.

(Wir wussten Adressen, KIGNI – – – war der Verbindungsmann zwischen AK und uns. Die krassen Unterschiede zwischen AK und AL war noch nicht. AK war national und antisemitisch und AL war nicht antisemitisch. AK hat in Lemberg deshalb Juden aufgenommen, weil der Druck der Deutschen in Lemberg viel staerker war wie in irgendeinem anderen Gebiet.)[16]

From the context, and in view of Wiesenthal's earlier statements concerning his unit, as to “the Russian partisans” and “the Russian liaison man,” “us” in the above passage would seem to refer to the AL, the military arm of the Communist regime the Soviets were to install in Poland at the end of the war.

Whatever the precise identity of the partisan group Wiesenthal claims to have served in, the question remains: Which, if any, of Wiesenthal's accounts of what he was doing between October 1943 and June (or is it January) 1944 is to be believed?

In the Hands of the Gestapo(?)

As has been mentioned, Wiesenthal claims in his memoirs to have been recaptured in an apartment in Lvov, with a pistol, a diary, and a list of SS men and their crimes, by two Polish detectives and an SS man on June 13, 1944. This version contrasts markedly with Wiesenthal's affirmation in 1954 that his recapture took place in a barn near Lemberg, where he claims to have been discovered by the Gestapo and the SD (Sicherheitsdienst, the security service of the German National Socialist Workers' Party) on January 13, 1944 (see above).

That Wiesenthal's sworn 1948 account of his recapture differs, once more, from his other stories will by now probably not surprise the reader. To be sure, his 1948 version exhibits similarities to that in The Murderers Among Us: he is captured, armed, hiding under the floor in an apartment in Lvov on June 13, 1944. According to his 1948 interrogation, however, Wiesenthal had on him not a diary and a list of SS misdeeds, but “different notes,” “certain notes regarding the entire partisan area of operations” (“verschiedene Aufzeichnungen,” “gewisse Aufzeichnungen ueber das gesamte Partisanengebiet”).[17]

Both in 1948 and when composing his memoirs, Wiesenthal was quite conscious that:the fate of an escaped Jew who had fallen into the hands of the Germans in 1944 armed with a pistol and either a list of SS war criminals or detailed notes on partisan activity would be regarded as rather precarious. In the memoirs, Wiesenthal is taken to a police outpost on Smolki Square, where he has his first bit of good fortune, for unbeknownst to the SS man, a venal Polish policeman relieves him of his pistol: “If a German had found the gun, he would have shot Wiesenthal at once.”

Then:

From Smolki Square, Wiesenthal was taken back to the concentration camp. Only a few Jews had survived: tailors, shoemakers, plumbers – artisans the SS still needed for a while. Wiesenthal knew that after reading his diary and his list of SS torturers with specific details, the Gestapo would have enough evidence to hang him ten times.[18]

According to both his memoirs and his 1948 interrogation, Wiesenthal staved off a quick execution by slashing his wrists. Even then, according to his 1948 version, it was his notes on partisan operations which saved him:

… I owe it especially to this circumstance that I wasn't killed immediately like so many Jews, since the notes appeared to be very valuable and therefore I entered the hospital after my suicide attempt. It was very rare that a Jew was admitted to a prison hospital.

(… diesem Umstand verdanke ich speziell, dass ich nicht gleich wie soviele Juden umgelegt wurde, denn die Aufzeichnungen schienen sehr wertvoll zu sein und darum kam ich in ein Gefaengnisspital, nach dem von mir veruebten Selbstmordversuch. Das war ein sehr seltener Fall, dass ein Jude in ein Gefaengnisspital kam.)[19]

In The Murderers Among Us Wiesenthal's suicide attempt is prompted by the appearance of SS Oberscharführer Oskar Waltke, “perhaps the most feared man in Lvov.” Waltke, against whom Wiesenthal testified at his 1962 trial in Germany, is described in the following chilling terms:

Waltke, a cold, mechanical sadist, was in charge of the Gestapo's Jewish Affairs Section in Lwow. His speciality was to make Jews with false Polish papers confess they were Jews. He tortured his victims until they made the admission and then he sent them to be shot. He also tortured many Gentiles until they admitted to being Jews just to get it over with. Waltke's name had been on Wiesenthal's private list, which Waltke must have studied with great interest. Wiesenthal knew that Waltke wouldn't simply have him shot. He would first submit him to his very special treatment. As Wiesenthal was led into the dark courtyard where the truck from the Gestapo prison stood waiting, he took out a small razor blade that he'd kept concealed in his cuff for such a moment.

“Get in, Kindchen, quick!” Waltke said.

With two fast movements, Wiesenthal cut both wrists.[20]

Thereafter, according to his memoirs, Wiesenthal is committed to the prison hospital, where two more suicide attempts fail. There he is restored to health with “a special diet of strong soups, liver, and vegetables” prescribed by the solicitous sadist Waltke so that he can get on with his “interrogation” all the more quickly.

If Wiesenthal's memoirs and his interrogation in 1948 represent the truth accurately, this interrogation never took place, which makes the following sentence in his 1954 reparations application all the more interesting: “There [in the Lacki Gestapo prison] I was fearfully tortured by Unterscharführer Waltke and to put an end to these tortures, I cut open my veins” (“Dort wurde ich vom Unterscharführer Waldtke [sic] furchtbar gefoltert und um diese Folterungen ein Ende zu setzen, habe ich mir die Pulsadern aufgeschnitten”).[21]

How to account for the survival of a Jew caught with a gun and, to say the least, compromising documents? Is Wiesenthal's 1954 claim to have been tortured simply one more roccoco furbelow on his story of persecution, or do his other two accounts suppress an actual event which might have resulted in Wiesenthal's having been “turned,” and thus spared as a Gestapo agent? (One can speculate on what might have been Wiesenthal's fate had he escaped once more to his alleged partisan unit and been trapped in such contradictions about his treatment in the hands of the German secret police.)

“I Didn't Wish to Die… “

Wiesenthal's 1954 story of his recovery from his suicide attempt and his evacuation from Lvov in July 1944 is short and simple. After his torture by Waltke:

Although it was somewhat unusual, I was admitted to the prison hospital and was delivered on March 19, 1944 to the Lemberg [Lvov] Concentration Camp, which was just being established. There were in all about 100 inmates and a larger camp guard, which, under the leadership of Hauptsturmführer Warzok, preferred not to go to the front. In the camp I carried out small tasks for the camp command and the camp kitchen until July 19, 1944.

On July 19, 1944 – it was about 10 days before the Russian entry into Lvov – the camp was evacuated…

(Obwohl es etwas ungewöhnlich war, kam ich in das Gefängnishospital und wurde am 19. März 1944 in das sich neu formierende Konzentrationslager Lemberg eingeliefert. Es waren im ganzen c. 100 verschiedene Häftlinge und eine grössere KZ-Bewachung, die es unter der Leitung von Hauptsturmführer Warzok, vorgezogen hat, nicht an die Front zu gehen. In dem Lager verrichtete ich kleine Arbeiten für die Lagerkommandatur und KZ-Küche bis zum 19. Juli 1944.

Am 19. Juli 1944 – es waren ungefähr 10 Tage vor dem russichen Einmarsch nach Lemberg – wurde das Lager evakuiert . .)[22]

This dry account omits a dramatic incident recounted in both Wiesenthal's memoirs and in his 1948 interrogation, whereby the “Nazi”-hunter narrowly escaped execution thanks to a providential Soviet aerial attack.

According to The Murderers Among Us, Wiesenthal was to be tortured at last by the fiendish Waltke on July 17, on which day he and the other prisoners were summoned to the prison courtyard. There Wiesenthal was assigned to a group of non-Jews slated for execution. Wiesenthal describes what happened next as follows:

“We were probably going to be buried in a large mass grave,” Wiesenthal remembers. “I looked at the others the way some people on an airplane look at their fellow travelers. If there should be a crash, they are thinking, these will be one's companions in death. On the other side of the courtyard I saw a group of Jews. I wished I could be buried with them, not with the Poles and Ukrainians, but how could I get there? Suddenly there was a roar in the sky above us, and an explosion shook the courtyard. From Sapieha Street a cloud of fire and smoke went up into the air. The files from the tables were scattered all over the courtyard, and there was terrific confusion. I quickly ran across the courtyard and joined the Jews. A minute later two SS men put us on a truck and brought us back to the Janowska [i.e., Lemberg] concentration camp.”[23]

Herewith the same incident in his sworn statements of 1948:

On July 20 I was to be released from the prison hospital. We were taken to the prison yard, where the entire Gestapo and the SS and Police-Leader of Galicia were. They sorted us out according to the crime[s] we were charged with. In this way I was immediately selected for death, as a partisan chief…

On the same day on which we stood in the yard, 11 o'clock in the morning, where unexpectedly there was a Soviet attack and some bombs fell, there arose confusion and a cloud of dust of about 200 meters [in height?]. The Gestapo gentlemen ran away immediately and a small group stood there. I didn't wish to die and exploited this confusion and ran the 20 steps to this Jewish group. We were all driven once again into the jail and I together with this group. Then there was an air alarm. An auto with sirens was driven around for this purpose. After an hour there was again an all-clear. Then it was, Jews out. A car came from Lemberg Concentration Camp to pick up the Jews.

(Am 20. Juli sollte ich vom Gefaengnisspital entlassen werden. Am 16. Juli kam die Sowjetische [sic] Offensive. Wir wurden auf den Gefaengnishof geholt, wo die gesamte Gestapo und der SS- u. Polizeifuehrer von Galyzien war. Die haben uns sortiert, je nach dem Verbrechen, das uns zur Last gelegt wurde. Auf diese [sic] Weise wurde ich sofort aussortiert zum Tode, als Partisanenhaeuptling…

An demselben Tag, wo wir im Hof standen, 11 Uhr vormittags, wo unverhofft ein sowjetischer Angriff war und einige Bomben fielen, entstand ein Durcheinander und eine Staubwolke von ungefaehr 200 m. Die Gestapo-Herren liefen gleich weg und da stand eine kleine Gruppe. Ich wuenschte nicht, dass ich sterben sollte und habe dieses Durcheinander ausgenuetzt und bin diese 20 Schritte zu dieser juedischen Gruppe gelaufen. Dann war Fliegeralarm. Es ist zu diesem Zweck ein Auto mit Sirenen herumgefahren. Nach einer Stunde wurde wieder Entwarnung. Dann hiess es, Juden raus. Es kam ein Auto vom K.L. Lemberg, um die Juden abzuholen.)[24]

For what it's worth, then, Simon Wiesenthal's sworn testimony of 1948 is that he was saved because he was a Jew as late as July 1944!

Conclusions

A sustained comparison of his several accounts of his evacuation westward, all of them differing in numerous particulars, will not be

undertaken here. The purpose of this brief study has been to make an internal criticism of Wiesenthal's credibility on his war years as reflected in several authoritive accounts he has provided of them, two of them sworn documents and the other his published memoirs.

The evident fact that Wiesenthal has more than once altered his story of the six most important years of his life must be considered in connection with his credibility as a “Nazi”-hunter. The ongoing and intensifying hunt for World-War-II criminals (so long as they were Germans, or German allies, accused of mistreating Jews or Communists) has brought to grief more than one man unable to account for what he was doing, in minute detail, forty-five years ago.

Thus John Demjanjuk, whose inability to remember in precisely which prison camp or holding pen he was held in at any given date contributed to his framing as “Ivan the Terrible” in Jerusalem. So Frank Walus, the wartime forced laborer from Poland whom Wiesenthal claimed to have documented as a member of the Gestapo until such humanitarians as Jerome Brentar of Cleveland were able to unearth insurance records which proved otherwise. It is time that competent authorities, in the United States and elsewhere, made a determined effort to establish the facts of Simon Wiesenthal's wartime career, by whatever means necessary. It is suggested that this time, if Mr. Wiesenthal is deposed under oath, appropriate penalties be imposed for deliberate misstatements.

Notes

| [1] | The Wiesenthal interrogation is contained on one of the 91 rolls at the Archives entitled “Records of the U.S. Nuernberg War Crimes Trials Interrogations, 1946-1949” (Copy 1019, No. 79). These 91 rolls contain nearly 15,000 pretrial interrogation transcripts of over 2,250 individuals, conducted by the Interrogation Branch of the Evidence Division of the Office, Chief of Counsel for War Crimes (OCCWC). The orthography of the transcript, which among other things indicates the umlaut with the letter “e” rather than by the dieresis, has been followed above. : |

| [2] | This statement, “Eidesstattliche Erklärung uber die Zeit meiner Verfolgung,” has been published in Simon Wiesenthal: Dokumentation, by Robert Drechsler, Vienna: Dokumente zur Zeitgeschichte, 1/1982 (July, 1982). Drechsler's account of Wiesenthal's life presents much useful informaton, particularly in regard to Wiesenthal's sustained legal squabbles with Bruno Kreisky and others, including Drechsler himself. The document cited was submitted to the “State Pension Board” (Landesrentenbehörde in Düsseldorf (North Rhine/Westphalia), is dated August 24, 1954, and bears Wiesenthal's address in Linz, Austria. |

| [3] | The Murderers Among Us: The Simon Wiesenthal Memoirs by Simon Wiesenthal (edited and with an introductory profile by Joseph Wechsberg, New York; Bantam Books, third printing, 1973. Following the usage in the title, we have referred to this book as Wiesenthal's “memoirs”; purists might style it his “authorized biography.” Perhaps it could be said to lie somewhere between the two genres. |

| [4] | The Murderers Among Us, p. 25. |

| [5] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 27, 1948, p.1. |

| [6] | According to historian Richard C. Lucas, at the time of the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland in 1939, “Jews in cities and towns displayed Red flags to welcome Soviet troops, helped to disarm Polish soldiers, and filled administrative positions in Soviet-occupied Poland… The Soviets with Jewish help shipped off the Polish intelligentsia to the depths of the Soviet Union. Some monasteries and convents were turned over to the Jews.” The Forgotten Holocaust, Lexington, Ky.: The University Press of Kentucky, 1986,p.128. The new rulers of Lvov and their Jewish helpers were just as unwelcome to the city's Ukrainians. |

| [7] | The Murderers Among Us, pp. 28f. |

| [8] | The Murderers Among Us, p. 29. |

| [9] | “Eidesstattliche Erklärung uber die Zeit meiner Verfolgung,” in Drechsler, Simon Wiesenthal, p. 133. |

| [10] | In Drechsler, Simon Wiesenthal, p. 135. |

| [11] | The Murderers Among Us, pp. 33ff. |

| [12] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 27, 1948, p. 2. |

| [13] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 28, 1948, p. 2. |

| [14] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 28, 1948, p. 2. |

| [15] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 28, 1948, p. 5. |

| [16] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 28, 1948, p. 4. |

| [17] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 28, 1948, pp. 4f. |

| [18] | The Murderers Among Us, p. 35. |

| [19] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 28, 1948,p. 5. |

| [20] | The Murderers Among Us, p. 35. |

| [21] | In Drechsler, Simon Wiesenthal, pp. 133f. |

| [22] | In Drechsler, Simon Wiesenthal, p. 134. |

| [23] | The Murderers Among Us, pp. 36f. |

| [24] | Interrogation of Simon Wiesenthal, May 28, 1948, p. 6 |

(Copies of Wiesenthal's secret 1948 interrogation, together with an English translation, may be obtained from IHR [check www.ihr.org for that offer; ed])

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 8, no. 4 (winter 1988), pp. 489-503

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: CODOH also has posted a revised version of this paper without illustrations at codoh.com/node/84