Pages from the Auschwitz Death Registry Volumes

Long-Hidden Death Certificates Discredit Extermination Claims

Over the years, Holocaust historians and standard Holocaust studies have consistently maintained that Jewish prisoners who arrived at Auschwitz between the spring of 1942 and the fall of 1944, and who were not able to work, were immediately put to death. Consistent with the alleged German program to exterminate Europe's Jews, only able-bodied Jews who could be “worked to death” were temporarily spared from the gas chambers. Holocaust historians also agree that no records were kept of the deaths of the Jews who were summarily killed in the camp's gas chambers because they were too old, too young or otherwise unable to work.[1]

However, Auschwitz camp death records – which were hidden away for more than 40 years in the Soviet Union – cast grave doubt on these widely accepted claims.

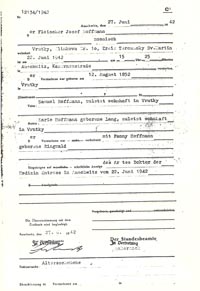

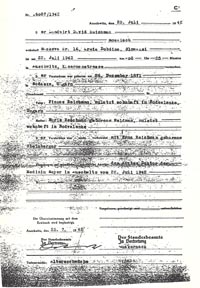

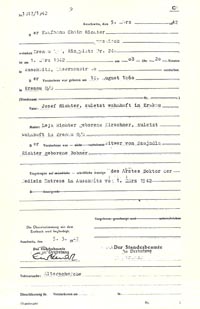

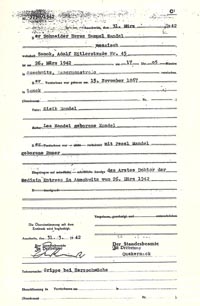

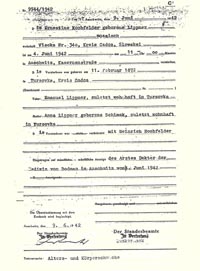

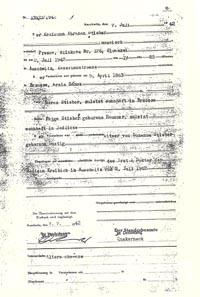

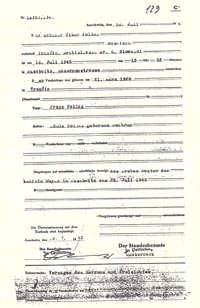

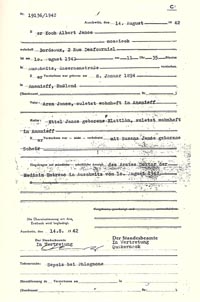

Inmate deaths at Auschwitz were carefully recorded by the camp authorities on certificates that were bound in dozens of death registry volumes. Each “death book” (Sterbebuch) contains hundreds of death certificates. Each certificate meticulously records numerous revealing details, including the deceased person's full name, profession and religion, date and place of birth, pre-Auschwitz residence, parents' names, time of death, and cause of death as determined by a camp physician.

These death registry volumes are designated as “secondary books” (Zweitbücher), suggesting the existence of a still-inaccessible set of “primary books.”

The death registry volumes fell into Soviet hands in January 1945 when Red Army forces captured Auschwitz. They remained inaccessible in Soviet archives until 1989, when officials in Moscow announced that they held 46 of the volumes, recording the deaths of 69,000 Auschwitz inmates.

These 46 volumes partially cover the years 1941, 1942 and 1943. There are just two or three volumes for the year 1941, and none at all for the years 1944 or 1945.[2] It is not clear why so many volumes are still missing. According to informed International Red Cross officials, the most likely explanation is that they were misplaced by the Soviets, and might therefore turn up later. (There is no indication that Auschwitz camp authorities made any effort to destroy any of the volumes.)[3]

“No one seems to know yet what become of the numerous missing volumes,” the journal Red Cross, Red Crescent has reported. “Are they still gathering dust in one of the numerous archives throughout the [former] USSR? Anything is possible, but this last hypothesis seems most likely. The mere thought that there are more than 3,250 archival centers in the USSR is enough make anyone's head spin.”[4]

Russian officials have permitted an agency of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) – the International Tracing Service in Arolsen, Germany – to make copies of the 69,000 death certificates. Microfilm copies of the documents have reportedly also been given to the American Red Cross, and the original volumes have been turned over to the Auschwitz State Museum in Poland.

Although archive officials have not permitted independent researchers to freely examine and evaluate the death registry volumes, the IHR recently obtained copies of 127 of the death certificates from German journalist and researcher Wolfgang Kempkens, who obtained copies of more than 800 of them from sources in Poland and Russia.

Published here – to our knowledge for the first time anywhere – are facsimile reproductions of 30 of these certificates. (Because of the Journal's page size, the documents reproduced here are reduced to 55 percent of original size.)

In selecting which certificates to reproduce here, preference has been given to those recording the deaths of Jewish prisoners who were indisputably too old to have been able to work.

Consistent with the Sterbebuch records, other German wartime documents show that a very high percentage of the Jewish inmates at Auschwitz were not able to work, and were nevertheless not killed.[5]

For example, an internal German telex message dated September 4, 1943, from the chief of the Labor Allocation department of the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office (WVHA), reported that of 25,000 Jewish inmates in Auschwitz, only 3,581 were able to work. All of the remaining Jewish inmates – some 21,500, or about 86 percent – were unable to work.[6]

This is also confirmed in a secret report dated April 5, 1944, on “security measures in Auschwitz” by Oswald Pohl, head of the WVHA agency responsible for the concentration camp system, to SS chief Heinrich Himmler. Pohl reported that there was a total of 67,000 inmates in the Auschwitz camp complex, of whom 18,000 were hospitalized or disabled. In the Auschwitz II camp (Birkenau), supposedly the main extermination center, there were 36,000 inmates, mostly female, of whom “approximately 15,000 are unable to work.”[7]

The evidence shows that Auschwitz-Birkenau was, in fact, established primarily as a camp for Jews who were not able to work, including the sick and elderly, as well as for others temporarily awaiting assignment to other camps.[8]

Along with the two documents above, the long-hidden certificates reproduced on the following pages discredit a central pillar of the Holocaust extermination story. As revealing as these documents are, though, there is little doubt that a careful examination of all of the many thousands of documents in the Auschwitz death books – as well as other, still-inaccessible wartime records – would bring us much closer to finding definitive answers to the central questions of Germany's wartime Jewish policy. It is high time for archival officials in Poland, Germany, Russia and Israel to open all their records to independent scholars.

Notes

| [1] | Probably the most often cited “evidence” for extermination at Auschwitz are the “confessions” and “affidavits” of former camp commandant Rudolf Höss. See, for example, Höss affidavit of April 5, 1946 (Nuremberg document 3868-PS), and: Rudolf Höss, Death Dealer: The Memoirs of the SS Kommandant at Auschwitz, Steven Paskuly, ed. (Buffalo: Prometheus, 1992), pp. 27, 31, 32, 34, 157, 159.; As Prof. Robert Faurisson has explained, the Höss “confessions” are error-ridden statements obtained by torture. See: R. Faurisson, “How the British Obtained the Confessions of Rudolf Höss,” The Journal of Historical Review, Winter 1986-87, pp. 389-403.; Other often-cited “eyewitness accounts” confirming the alleged Auschwitz extermination program include: Miklos Nyiszli, Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account (Fawcett Crest pb. edition, 1985?), pp. 23-24.; Olga Lengyel, Five Chimneys (Granada, pb., 1981), pp. 83. |

| [2] | Jean-Louis Amar, “Death Camps: The Archives Open,” Red Cross, Red Crescent, January-April 1990, pp. 24-26. This journal is apparently an official publication of the Swiss-based International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). |

| [3] | E. Schulten, “Endlich Glasnost… ,” Waldeckische Landeszeitung, Nov. 2, 1989. |

| [4] | J.-L. Amar, “Death Camps: The Archives Open,” Red Cross, Red Crescent, January-April 1990, p. 26. |

| [5] | This has recently been obliquely confirmed by Auschwitz State Museum official Franciszek Piper. See: F. Piper, “Estimating the Number of Deportees to and Victims of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Camp,” Yad Vashem Studies (Jerusalem: 1991), Vol. 21, pp. 70-71. |

| [6] | Helmut Eschwege, ed., Kennzeichen J (Berlin: 1966), p. 264. Source cited: Archives of the Jewish Historical Institute of Warsaw. German document No. 128. |

| [7] | Nuremberg document NO-021. Published in: Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals (Washington, DC: 1949-1953), Vol. 5, pp. 384-385. (This is also known as the NMT “green series.”) |

| [8] | This is also the considered view of Dr. Arthur Butz. See: A. Butz, The Hoax of the Twentieth Century (IHR, 1983), p. 124. |

The cover of an Auschwitz death registry volume (Sterbebuch) containing 1,500 certificates from July and August 1943.

This Auschwitz camp death certificate reports that prisoner Josef Buck, a Jewish teacher from Kattowitz, was 65 years old when he died on August 1, 1941. “Weakness of old age” is given as the cause of death.

Josek [sic] Nisenkorn, a Jewish laborer, was 71 years old when he died in Auschwitz on August 11, 1941. “Weakness of old age” is given as the cause of death by camp physician Dr. Siegfried Schwela, who himself later died of typhus.

Chaim Richter, a Jewish salesman, was 81 years old when he died in Auschwitz on March 1, 1942, of “weakness of old age.”

Samuel Mandel, a Jewish tailor, was 74 years old when he died in Auschwitz on March 26, 1942. Physician Dr. Entress reported the cause of death as “influenza with heart failure.”

Ernestine Hochfelder, a Jewish inmate who had been deported to the camp from Slovakia, was 70 years old when she died in Auschwitz on June 4, 1942. “Physical weakness and old age” is cited as the cause of death.

Abraham Stieber, a Jewish salesman from Slovakia, was 79 years old when he died on July 2, 1942, of “old age.”

Tibor Pollak, a Jewish secondary school student from Slovakia, was 14 years old when he died on July 26, 1942. Camp physician Dr. Meyer recorded “heart and circulatory failure” as the cause of death.

Albert Janos, a Jewish cook born in Russia, was deported to Auschwitz from Bordeaux, France. He was 48 years old when he died on August 10, 1942. Camp physician Dr. Entress recorded the cause of death as sepsis with inflammation of tissues.

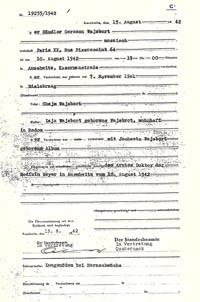

Gerszon Wajsbort [sic], a Jewish merchant deported to Auschwitz from Paris, was 40 years old when he died on August 10, 1942. Camp physician Dr. Meyer recorded the cause of death as accumulation of fluid in the lungs and heart failure.

Armin Horn, a Jewish salesman deported to the camp from Slovakia, died on August 19, 1942, at the age of 70. Camp physician Dr. Thilo recorded the cause of death as “accumulation of fluid in the intestine and weakness of old age.”

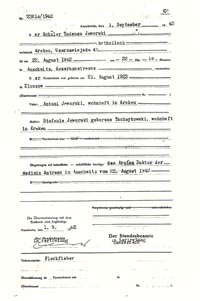

Tadeusz Jaworski, a Catholic Pole from Krakow, had just turned 19 years old when he succumbed to typhus on August 22, 1942.

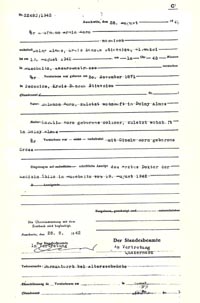

Abraham Trijtel, a Jewish student from the Netherlands, was 14 years old when he died on September 4, 1942, of “acute inflammation of the stomach intestine.”

Jettchen Fuld, a Jewish inmate, was 67 when she died on October 10, 1942. Old age and physical weakness is given as the cause of death.

Salomon Serlui, a Jewish laborer from the Netherlands, was 67 when he died in Auschwitz on October 16, 1942. Camp physician Dr. Kremer reported a stomach ulcer as the cause of death.

René Hirschfeld, a Jewish tailor born in Berlin in 1878, was 64 when he died on November 2, 1942. Camp physician Dr. Kitt reported “weakness of old age” as the cause of death.

Freide [sic] Littmann, a Jewish inmate from Leipzig, Germany, was 70 when she died of “old age”on January 11, 1943.

Wolf Eisenhändler, a Jewish student from Berlin, was 14 when he died on January 13, 1943. “Sepsis with pneumonia” is reported as the cause of death.

Josephine Kohn, a Jewish inmate born in Hungary who had been living in Leipzig, was 69 years old when she died on February 10, 1943. Auschwitz camp physician Dr. Kitt reported “weakness of old age” as the cause of death.

Emil Kaufmann, a Jewish attorney deported from Germany, was 78 years old when he died of “old age” on February 15, 1943. “Weakness of old age” is given as the cause of death.

Julius Sonnenberg, a salesman from Germany, was 65 when he died on February 27, 1943, of “angina pectoris.” His religion is cited as “non-believing, formerly Jewish.”

Abraham Blok, a Jewish butcher from the Netherlands, was 70 years old when he died of “old age” on March 6, 1943.

Franz Waitz, a Catholic laborer, was 67 years old when he succumbed to typhus on June 21, 1943. His death was certified by Dr. Josef Mengele, the Auschwitz camp physician who was sensationally stigmatized after the war as the “angel of death.”

Josef Daniel, a Catholic laborer from rural Moravia, was 18 years old when he ended his life on June 21, 1943, by “suicide by high-voltage electrical current.”

Max Lichtenstaedt, a Jewish salesman from Berlin, was 73 years old when he died in Auschwitz on July 21, 1943. “Uraemia” is given as the cause of death.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 12, no. 3 (fall 1992), pp. 265-298

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a