Remer Dies in Exile

War Hero Fled to Spain to Avoid Thought Crime Imprisonment

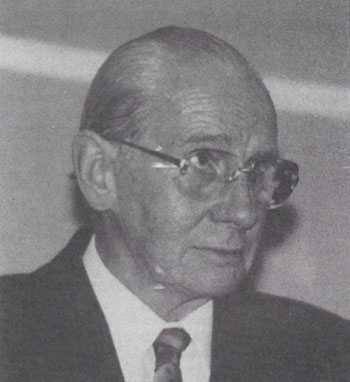

Otto Ernst Remer – a wartime German army officer who played a key role in putting down the July 1944 plot against Hitler, and an important postwar revisionist publicist – died on October 4, 1997, at the age of 85. Since 1994 he had been living in exile in the Spanish resort of Marbella. In poor health for some months, he died of natural causes.

He is survived by his wife, Anneliese. At the time of his death, it was announced that his remains would be cremated, with the ashes to be buried later in Germany.

Born on August 18, 1912, Remer volunteered for service in the German army in 1930. During the Second World War, he served as a front-line officer in France, the Balkans and on the eastern front.

After promotion to Major and then Colonel, in 1944 he was chosen to command the Grossdeutschland guard regiment in Berlin. In this post, the 31-year-old officer played a historically pivotal role in putting down the attempt by a small circle of insurgent officers to kill Hitler and seize control of the government.

On the afternoon of July 20, 1944, General Paul von Hase, the military commander in Berlin and a leader in the anti-Hitler conspiracy, announced to Remer that Hitler was dead, that civil disorder had broken out, and that the army was assuming overall authority in Germany. Hase ordered Remer immediately to seal off key government buildings in central Berlin.

Hesitating to carry out this highly unusual order, Remer decided to contact Joseph Goebbels to confirm its validity. After telling the skeptical and uncertain Remer that Hitler was not dead, the propaganda minister and Berlin Gauleiter arranged for him to speak directly with the Führer by telephone at his military headquarters in East Prussia. (Although the bomb planted by conspiracy leader Colonel Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg during a conference had killed four officers, Hitler escaped with only minor injuries.)

Major Remer, can you hear me, do you recognize my voice?, Hitler began. After explaining that an attempt on his life had failed, he gave Remer complete authority in Berlin to suppress the conspiracy. Remer and his men moved quickly to put down the revolt, which had been poorly planned and organized.

Five months later, Remer commanded the elite Panzer Führer-Begleitbrigade during the ill-fated Battle of the Bulge offensive. Following his promotion by Hitler on January 30, 1945, to the rank of Major General he was given command of tens of thousands of soldiers of the legendary Panzer Führer-Begleitdivision. During the wars final months, he and his men fought off vastly superior Soviet forces, thereby rescuing hundreds of thousands of refugees who were fleeing the advancing Red troops.

Remer showed exemplary courage and valor in combat, and was wounded numerous times in battle. He was awarded some of the nations most distinguished military decorations, including the Knights Cross of the Iron Cross, the German Cross in Gold, the Oak Leaves of the Iron Cross, the Golden Wounded Badge, and the Silver Close Combat badge.

At the end of the war he came into American captivity, and remained a prisoner of war until 1947. During this period, the American commander of a camp for German prisoners, First Infantry Division officer Stanley Samuelson, said of him: Of the 87 German generals in this camp, General Remer is the only one whom I respect as courageous and honorable.

Remer played a leading role in the formation of the postwar Socialist Reich Party, which, after winning 16 seats in a state parliament, was banned in 1952. Remer than lived in exile for several years in Egypt and Syria. He also wrote two books, including Conspiracy and Treason Around Hitler (Verschwörung und Verrat um Hitler), a memoir and study reviewed by H. Keith Thompson in the Spring 1988 Journal.

As a featured speaker at the Eighth (1987) Institute for Historical Review Conference, Remer spoke on My Role in Berlin on July 20, 1944. (His address was published in the Spring 1988 Journal, and is available on both audio- and video-tape from the IHR.)

In October 1992 a German court in Schweinfurt sentenced him to 22 months imprisonment for popular incitement and incitement to racial hatred because of allegedly anti-Jewish Holocaust denial articles that had appeared in five issues of his tabloid newsletter, Remer Depesche. The judges in the case flatly refused to consider any of the extensive evidence presented by Remers attorneys. (See the March-April 1993 Journal, pp. 29-30, and the May-June 1994 Journal, pp. 42-43.)

To avoid imprisonment, in February 1994 Remer sought exile in Spain. (See the July-August 1995 Journal, pp. 33-34.) German authorities sought his extradition, but Spains highest court rejected these requests on the basis that Remers thought crime was not illegal in Spain. Nevertheless, until the final weeks of his life, German authorities persisted in their efforts to extradite the dying octogenarian so that he could be imprisoned in Germany.

Many of the numerous newspaper reports that have appeared about Remer over the years have contained demonstrable falsehoods. For example, he has repeatedly, and inaccurately, been referred to as a former SS man or SS officer. In fact, he was never even a National Socialist party member.

Newspapers also reported that Remer denied the murder of Jews or declared that no Jews were murdered under the National Socialist regime. Actually, Remer pointed out, I have never denied that Jews were killed during the Third Reich, but have only disputed the figures of Jews who died in Auschwitz and the alleged method of killing (that is, in gas chambers).

In challenging the gassing claims, Remer cited the various forensic studies of the alleged gas chambers at Auschwitz, particularly the investigations carried out by German chemist Germar Rudolf and American gas chamber specialist Fred Leuchter.

The Remer case points up the strange and even perverse standards that prevail in Germany today. Although his crime was a non-violent expression of opinion, to dispute claims of mass gassings in wartime concentration camps is regarded in todays Germany as a criminal attack against all Jews, who enjoy a privileged status there.

More than half a century after the end of the Third Reich and the Second World War, Germans are ceaselessly exhorted to never forget the anti-Jewish measures of the Hitler era, to atone for what is called the most terrible crime in history, and to regard themselves as a nation of criminals and moral misfits. As a further expression of the countrys national masochism, the July 1944 conspirators are officially venerated, while outstanding wartime combat heroes and selfless patriots such as Remer are dishonored.

Particularly in Germany, the struggle on behalf of historical truth is not merely an academic question – it is an issue of national survival.

If Germany were ever to find itself in another major war, it would be suicidal stupidity to cite as role models for its soldiers and officers the individuals who, at a time of national emergency, tried to assassinate the nations leader and overthrow the government in a murderous putsch.

Every nation with a healthy survival instinct naturally venerates, particularly in time of war, individuals of exemplary self-sacrifice, patriotism, and heroism – men of the caliber of Otto Ernst Remer.

–M. W.

Major General Remer, right, commander of the “Panzer Führer-Begleitdivision,” talks with Major General Maeder during the battle near Lauban (lower Silesia) in March 1945.

Remer Speaks

The uprising, or, better said, the revolt, of July 20, 1944, failed not because of my intervention, but rather because of the inner lack of goals and conceptualization by its heterogeneous participants, apparently a privileged but subdued nobility class, who were, of course, united in their rejection of Hitler, but who were completely disunited in all other issues. The putsch failed because it began with unclear ideas, was prepared with insufficient means, and was carried out with almost astonishing awkwardness. Moreover, it is also known that no political support was promised from outside of Germany, which meant that the only possible result would have been unconditional surrender.

No one needs to ask what would have happened if the July 20, 1944, undertaking had succeeded. The German eastern front, which at that time was involved in extremely serious defensive battles, would undoubtedly have collapsed as a result of the civil war that inevitably would have broken out, and the attendant interruption of supplies… A collapse of the eastern front, however, would not only have meant the deportation of further millions of German soldiers into the death camps of Russian captivity, but would also have prevented the evacuation of countless women and children who lived in the eastern territories of the Reich, or who had been evacuated to those areas as a result of the terror attacks from the air by the western Allies.

Precisely because of his experiences on the eastern front, every thinking soldier knew what would happen to us if we were to lose this war. German soldiers were quite deeply convinced of the necessity of this struggle in the interest of the survival of our continent. We had not attacked Russia out of pure zeal to conquer. Rather, we were forced to act because the Soviets had deployed superior forces of more than 256 divisions in order to invade Europe at an opportune hour.

During my lifetime I have gotten to know and understand more than 50 countries, particularly in the Arab world and black Africa. These countries live under diverse political systems. In contrast to us, these nations all love and respect their own homelands, and are proud of their own countries and traditions.

The system of “reeducation” after 1945 has turned the Germans into a neuroticized people. This spiritual-psychic condition of society in the [German] Federal Republic thereby renders it incapable of self-awareness or of taking decisive counter-measures against the leftist organized revaluation of the natural life order.

A democracy is not good and acceptable because it calls itself a democracy, but rather when it recognizes and respects the traditional and living values of its own national community. I also believe that in every western democratic country, including here in Germany, no one can be happy about a democracy that does not also have a positive regard for its own people, state and nation. Contrary to the prevailing dogma, I have gained the impression that human beings are not equal, if for no other reason than on the basis of their very different cultural views. Nevertheless, I have observed that everywhere in the world, nationalists and those who love their own countries are able to speak with each other in the same language and understand each other, which is not the case among democrats of each country.

When one observes the tumultuous defamation of the Third Reich and the continual and repulsive self-accusations, one has to ask himself: is Hitler still so strong and the German Federal Republic so weak that the ignorant citizens of Germany can be convinced of the value of this democracy only by repetitiously repeating the old confessions of self-guilt? I do not believe so. In the long run, the historical truth cannot be suppressed.

Dangerous Reputation

“One of the best ways to get yourself a reputation as a dangerous citizen these days is to go about repeating the very phrases which our founding fathers used in the great struggle for Independence.”

—Charles A. Beard (1874-1948)

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 17, no. 1 (January/February 1998), pp. 7-9

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a