The Changing Story: Early Doubts

From the very beginning there were grave doubts about allegations of mass killings of European Jews. Although such reports were a major feature of the Allies’ “psychological warfare” campaign during the Second World War, top British and American officials in a position to know what was going on in German-ruled Europe did not believe what their own governments were telling the world.

In July 1943, the chairman of the Britain’s Joint Intelligence Committee, Victor Cavendish-Bentinck, commented: “The Poles, and to a far greater extent the Jews, tend to exaggerate German atrocities in order to stoke us up.” At the suggestion of the British government, it was therefore agreed to delete the reference to gas chambers from a joint Allied declaration on German atrocities in Poland that was issued later that year by Roosevelt, Churchill and Stalin. (B. Wasserstein, Britain and the Jews of Europe, 1939–1945 [London: 1979], pp. 295–96.)

During the immediate postwar period – which saw a flurry of often grotesque anti-German atrocity propaganda as well as horrible “revelations” from the Nuremberg trials – a few thoughtful individuals remained skeptical. George Orwell, for example, wondered in May 1945: “Is it true about the German gas ovens in Poland?” (S. Orwell and I. Angus, eds., The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell [New York: 1968], Vol. 3, p. 371.)

Encyclopaedia Britannica Prudence

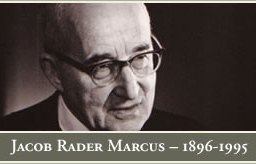

More remarkable, there is no mention of “extermination” or “gas chambers” in the early postwar editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, published from 1947 to 1956 (and perhaps earlier and later). Jewish historian Jacob Rader Marcus provided a prudent and generally accurate description of the wartime fate of Europe’s Jews in his essay on modern Jewish history published in these editions of the authoritative reference work. (“Jews,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1947 and 1956 editions, Vol. 13, p. 63 C.)

Under the heading “World War II and the Jews,” Marcus wrote:

In World War II the situation of Jewry in the mass settlements of eastern Europe was even worse, for the national socialists set out deliberately to destroy large numbers of Polish and Russian-Jewish civilians. If but a fraction of the atrocities reported were accurate, then many thousands of defenseless Jewish non-combatants, men, women and children, were butchered after September 1939 …

In the conquered lands, from France to Poland, practically all Jews lost their political and civil rights; their property and businesses were confiscated, and their children, in most lands, were driven out of the elementary and higher schools. They lost the right to freedom of movement and in some lands were even deprived of almost all cultural and recreational opportunities and social relations. Quite a number sought to ameliorate their lot by converting to Christianity, particularly in Slovakia, Croatia, Hungary and Italy …

In order to effect a solution of the Jewish problem in line with their theories, the Nazis carried out a series of expulsions and deportations of Jews, mostly of original east European stock, from nearly all European states. Men, frequently separated from their wives, and mothers from their children, were sent by the thousands to Poland and western Russia. There they were put into concentration camps, or huge reservations, or sent into the swamps, or out on the roads, into labour gangs. Large numbers of them perished under the inhuman conditions under which they laboured. While every other large Jewish centre was being embroiled in war, American Jewry was gradually assuming a position of leadership in world Jewry.

Marcus’ relatively reserved treatment of this issue, entirely ignoring the lurid horror stories then in wide circulation, is all the more noteworthy in light of his stature as an eminent scholar of Jewish history. He had studied in Germany during the early 1920s, receiving his doctorate from the University of Berlin in 1925. During his lifetime he authored more than 250 scholarly articles and numerous acclaimed historical studies, including The Rise and Destiny of the German Jew (1934), The Jew in the Medieval World (1938), and a four-volume work, United States Jewry, 1776–1985 (1989–93). At the time of his death in November 1995, Marcus was a distinguished professor of American Jewish history at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.

With the passage of time, the scholarly circumspection shown by Marcus in this Encyclopaedia Britannica article has become very rare, even among prominent scholars. Encouraged by an intense and growing media campaign in the United States, historians dealt with the wartime fate of Europe’s Jews in an ever more credulous, subjective and even quasi-religious fashion. This trend, which became particularly more pronounced after the 1970s, shows no sign of diminishing.

ndash; M. W.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 16, no. 4 (July/August 1997), pp. 38f.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a