The Ideal of Intellectual Freedom

A Brief History of "The Revisionist"

The recent passing of my friend Bradley Smith this past February stirred many memories of the work that we did together.[1] While we met face-to-face only once, we shared many hundreds (thousands?) of emails and countless phone calls. One project that we enthusiastically worked on together led ultimately to the creation of Inconvenient History in the summer of 2009. The ideas that led to the publication of this journal resulted from work and experiences from more than ten years prior.

The original idea was for a print journal entitled The Revisionist and the year was 1998. It was an exciting time for revisionism, but there was also a sense that something was missing. While the major revisionist websites had all been in full operation for a few years (CODOHWeb, VHO, Zündelsite, and the Institute for Historical Review), printed publications still seemed to be an important ingredient in the serious documentation of the case for revisionism.

At the time and for about 17 years prior, this space was filled by The Journal of Historical Review (JHR) published by the Institute for Historical Review. The JHR would continue publication until 2002, but already in 1998 it was clear that the Journal was not what it used to be. Perhaps the fracture with Willis Carto and Liberty Lobby contributed to the declining quality, perhaps it was other reasons altogether.[2] Nonetheless, in 1998 new revisionist voices were being heard throughout Europe and on the Internet, but rarely were they published in the JHR. Even big names like Germar Rudolf and Carlo Mattogno rarely found their way into the pages of the JHR. New names like Samuel Crowell would have to wait years before being picked up by the JHR.[3] I myself had submissions rejected. In the place of the cutting edge, the JHR’s pages were often filled with reprints by Revilo P. Oliver, Joe Sobran, and on one occasion even Mark Twain. My intent here is not to disparage the JHR or the editors and writers who contributed to its publication, but only to provide insight into my thinking at the time.

Source: The Widmann Collection.

The most significant competition to the JHR at the time was the new publication of Willis Carto, The Barnes Review (TBR). While TBR always looked nice and was published on time, the articles covered a very wide array of subjects, from antiquity to the modern day. Again, cutting-edge Holocaust revisionism rarely was featured in its pages. In fact, TBR did not publish an issue entirely dedicated to the Holocaust until 2001. The articles were generally written by a small cadre of Carto loyalists who were far from the cutting edge of what was happening in revisionist research at the time. Since the split with the IHR in 1994, most key figures in the revisionist movement sided (at least initially) with the IHR and were rarely if ever mentioned, never mind published, in the pages of TBR.

The one shining star on the scene of published revisionist scholarship was the new German language journal of Germar Rudolf, Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung (VffG), which appeared on the scene in March of 1997. Indeed, VffG was everything I was looking for in a revisionist journal; interesting well-referenced articles, cutting-edge scholarship; high quality publishing. The one obvious issue was that VffG was available only in the German language.

Source: The Widmann Collection.

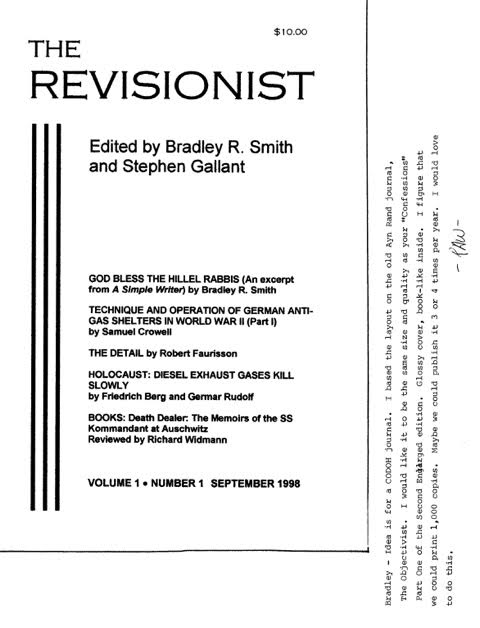

While it was clear that a publication of the size and quality of VffG in English was beyond our means, a publication of fewer pages could indeed be produced featuring similar cutting-edge works in English by those voices that were rarely heard outside of the Internet. In February of 1998 I created a sample cover and faxed it with a brief note to Bradley Smith:

“Bradley – Idea is for a CODOH [Committee for Open Debate on the Holocaust] journal. I based the layout on the old Ayn Rand journal, The Objectivist. I would like it to be the same size and quality as your Confessions Part One of the Second Enlarged edition. Glossy cover, book-like inside. I figure that we could print 1,000 copies. Maybe we could publish it 3 or 4 times per year. I would love to do this.”

Bradley responded, “The Revisionist. First reaction. I LOVE IT.”

Source: The Widmann Collection.

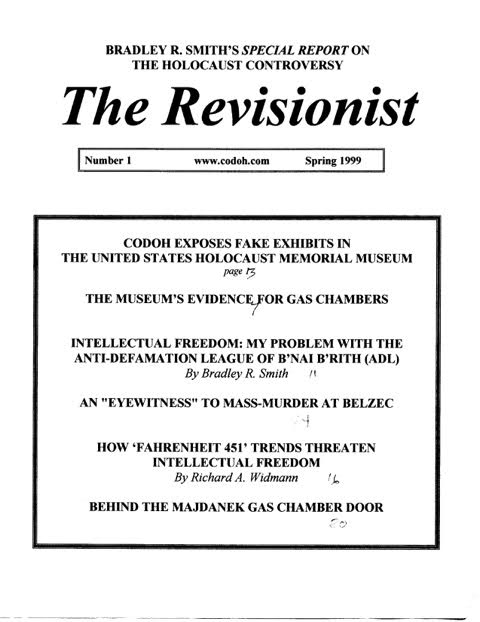

Over the next few months, the idea evolved. Bradley was more interested in what he had dubbed “The Campus Project” and his efforts to get the word about the Holocaust controversy out to students, who he believed were more intellectually honest and open to new ideas than most others including their professors. Rather than creating a publication for the revisionist community as I had originally envisioned, The Revisionist would become a vehicle to support the Campus Project. In addition, Bradley decided that he would give away 90% of every issue for free. In “A Note from the Publisher” in the first issue Bradley explained:[4]

“My idea – we’ll see how it works – is to print The Revisionist in the least expensive way – in this instance on newsprint – print as many copies as I can raise funds to pay for, and distribute them at no cost to those people who I believe have the most open minds and who are most willing to defend and even promote the ideals of intellectual freedom and a free press—students.

I will send TR to editors at college and commercial newspapers, to journalists on and off campus, academics, particularly in communications and history, and university presidents and others in administration. But it is students as a class who are the key to this project. It is among students where intellectual freedom is taken most seriously. It’s clear that we cannot depend on the professorial class to protect the ideal of intellectual freedom […].

Bradley continued explaining his plan to disseminate revisionism on campus,

“The simplest, and least expensive, way of reaching students with TR is to distribute it free as an insert in college newspapers on college campuses. To distribute 5,000 copies of The Revisionist in The Princetonian, say, might cost about $500.”

The first university to accept The Revisionist was Hofstra, where 5,000 copies were to be included in their newspaper the Chronicle. Needless to say, there was quite an uproar when university officials became aware of what had happened.

Source: The Widmann Collection.

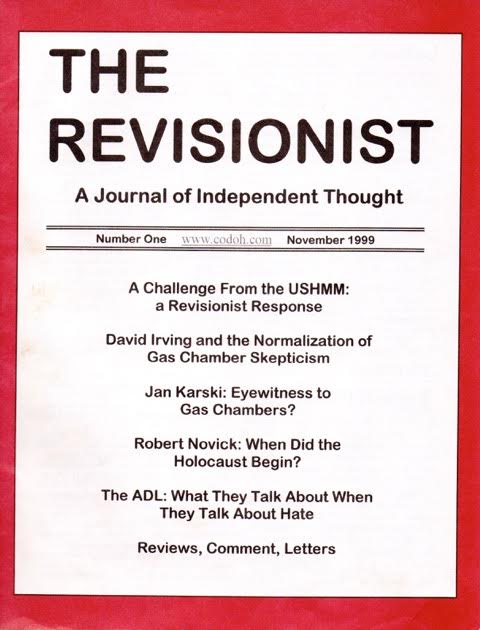

By January of 2000 a second issue was assembled by a small band of volunteers supporting Smith and me including Editor George Brewer and columnists Bill Halvorsen, Ted O’Keefe, Fritz Berg, and Ernest Sommers. As more and more schools accepted the magazine as an insert, the furor on campus escalated. Teachers and students set fire to The Revisionist No. 2 at St. Cloud University. A professor was quoted in the St. Cloud Chronicle cursing us, “May their myths burn in the fires of Hell!” Ironically, that issue featured my article, “How Fahrenheit 451 Trends Threaten Intellectual Freedom,” a widely distributed article arguing against censorship and the stifling of scholarship.[5] Such was the success of Issue No. 2 that a second printing was created and labeled “The Campus Edition.”

In March of 2000 the final issue No. 3 was published and distributed. Thousands of copies of each issue of The Revisionist were distributed on college campuses. The impact of the magazine insert was that hits on the CODOH website skyrocketed. Bradley announced to readers of Smith’s Report that documents were being accessed at a rate of 15,000 to 20,000 times daily.[6] By the end of the 1999-2000 academic year Bradley had distributed 42,000 copies of The Revisionist on campus.[7]

Source: The Widmann Collection.

Through all the ruckus and success of The Revisionist, No. 3 would be the last to be physically printed. The costs were too high, financial backers were too few; there was no way to continue publishing a free magazine. Bradley would change tactics and revert to small ads to be published in college newspapers. The success of his ever-changing tactics is the story for another day and another article.

While the “project” on campus had run its course, The Revisionist had sufficient life in it to keep going for quite some time. Editors and writers had been assembled and they still believed in what we were doing. There was still a sense that a quality revisionist journal in the English language was lacking. Today it might seem obvious, and yet at the time it was quite innovative, that The Revisionist could be published in an on-line format. The cost would be negligible. In addition, students could be directed to the main URL of The Revisionist in low-cost ads.

Source: The Widmann Collection.

Beginning with No. 4 in Spring of 2000 and running until No. 13 in 2002, The Revisionist would continue to publish cutting-edge revisionism, reviews, and commentary by a variety of revisionist authors. Another 87 articles would be written and published before The Revisionist published its final on-line issue. By late 2001 chief editor George Brewer had departed along with many key columnists. I picked up the chief editor role for the final three issues. With fewer and fewer writers, The Revisionist appeared to have finally run its course.

The vacancy in revisionism that The Revisionist was attempting to fill was still there, however. By early 2003, the gap in published English-language revisionist scholarship was even larger than it had been five years earlier. The JHR was now defunct and even new on-line scholarship in English seemed to be waning.

In February 2003, like a phoenix, The Revisionist rose up again. Now under the editorship of Germar Rudolf, a new journal was born. In its latest evolution, The Revisionist featured 120 pages of scholarship much in the style of the German-language VffG.

Germar Rudolf’s The Revisionist would continue through September 2005 when it was forced to cease due to ongoing prosecution and persecution of Germar Rudolf.[8] During this dark time of increased legal action and imprisonment of revisionists and censorship of their ideas and publications, it was clear that yet another reincarnation was needed.

Source: The Widmann Collection.

Modeled on the short-lived on-line journal The Revisionist, the first ideas for Inconvenient History were developed. Having learned from the experience, and with a new primary focus on countering the increasing battle against intellectual freedom, Inconvenient History was launched in the summer of 2009.

Taking our name from James J. Martin’s book, The Saga of Hog Island and Other Essays in Inconvenient History, we sought, and continue to seek, to revive the true spirit of the historical revisionist movement. Today, as I write these words seven years later, it is clear that my words from my first editorial published in the first issue of Inconvenient History still ring true:[9]

“Cutting through the exaggerations, lies and propaganda of the Holocaust story has to be the starting ground for any contemporary revisionist. The territory is plagued with the minefield of charges of “Holocaust denial,” “racism,” “anti-Semitism,” and “neo-Nazism.” Despite the persecution and insults, revisionists understand that the myths of the Holocaust have smothered out a proper and accurate understanding of the Second World War.”

While the fight for intellectual freedom is without a doubt a noble cause, it does at times feel like a lonely tilt at windmills. In fact, the image of Don Quixote was so striking that webmaster David Thomas used Pablo Picasso’s famous rendering as an image throughout the old CODOH website. It was always amusing to imagine Bradley tilting at windmills with several Sancho Panzas by his side. That image is no longer featured on the CODOH website because officials representing Pablo Picasso demanded that it be removed, or significant penalties and legal action would be taken.[10]

There are days when I am doubtful that Inconvenient History will last another year, or even another issue.[11] But I am strengthened by the knowledge that great causes and great ideas must always find a way. They will evolve, they will sometimes even die and rise from their own ashes, but they will always live on. I recall a line from the graphic novel turned action movie, V for Vendetta:

“Did you think to kill me? There’s no flesh or blood within this cloak to kill. There’s only an idea. Ideas are bulletproof.”

Not only are ideas bulletproof, but they are fireproof and flame retardant as well. Let this be a lesson to all would-be apprentice book burners and censors and especially the misguided professors and students of St. Cloud University who attempted to prevent the free exchange of inconvenient ideas by burning The Revisionist so many years ago. It is to their disgrace and futility that I dedicate this issue of Inconvenient History.

Notes:

| 1 | See my article, “Remembering Bradley R. Smith,” in Inconvenient History Vol. 8, No. 2, Summer 2016. Online: https://codoh.com/library/document/remembering-bradley-r-smith/ |

| 2 | See George Michael, Willis Carto and the American Far Right (Gainesville, Fla: University Press of Florida, 2008) especially Chapter 16 “Internecine Battles: The Struggle with the IHR.” |

| 3 | Crowell first appeared in the JHR Vol. 18, No. 4, July / August 1999 with his article, “Wartime Germany’s Anti-Gas Air Raid Shelters: A Refutation of Pressac’s ‘Criminal Traces.’” The article was available on-line through CODOHWeb as of 23 March 1997. The article even appeared in German translation in the December 1997 issue of VffG nearly 18 months earlier than the JHR’s version. |

| 4 | Bradley R. Smith, “A Note from the Publisher,” The Revisionist No. 1, November 1999, p.26. |

| 5 | For more on the burning of The Revisionist on the campus of St. Cloud State University, see Smith’s Report No. 68, April 2000. My anti-censorship article featured in that issue was published by several different sources. Most importantly it was included in Readings on Ray Bradbury Fahrenheit 451 as part of the Greenhaven Press Literary Companion to American Literature series. Online: https://codoh.com/library/document/how-fahrenheit-451-trends-threaten-intellectual/ |

| 6 | Smith’s Report No. 66, December 1999, p. 1. |

| 7 | Smith’s Report No. 69, June 2000, p. 2. |

| 8 | In 2005 Germar Rudolf was separated from his wife and child by US Immigration authorities and deported to Germany where he was imprisoned on account of his book Lectures on the Holocaust that he had published that summer. For a full account see Germar Rudolf, Resistance is Obligatory (Uckfield UK: Castle Hill Publishers, 2012). |

| 9 | Richard Widmann, “The Challenge to Revisionism,” Inconvenient History Vol. 1, No. 1, Summer 2009. Online: https://codoh.com/library/document/the-challenge-to-revisionism/ |

| 10 | The Don Quixote image is now broadly available on the Internet. For example, see Wikipedia at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Don_Quixote_(Picasso) |

| 11 | When we first announced our publication, friend and editorial advisor Arthur Butz said he doubted that we would last a year. We are pleased to have made him wrong on this occasion (perhaps he is, too). |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 8(3) 2016

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a