The Racism of the Early Mahatma Gandhi

One anomaly of modern liberalism is that it elevates scoundrels to be heroes, and denigrates heroes into scoundrels. And when it cannot do that, liberalism simply lies.

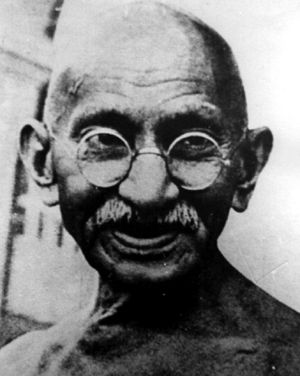

Such is the case with one of liberalism’s icons, Mahatma Gandhi. All over the world, the Indian leader Gandhi is held up as an icon of peace, pacifism, tolerance and brotherly love. Statues are erected to him, his “example” is taught to Western school children, and Hollywood has even made a film about him. In all of these instances, Gandhi is portrayed as the ultimate peacemaker, the role model of multi-culturalism.

Sadly, liberalism and the truth have seldom met. For in reality, Gandhi was a first-class Indian racist who despised not only Blacks, but also lower-caste Indians!

Those who have been subjected to the “conventional” Gandhi propaganda will know that he was born in India, studied to become an attorney in England, spent many years “organizing passive resistance” in South Africa, and then returned to India to lead the passive resistance movement against British rule in that country. He was finally assassinated by one of his own kind.

Gandhi – the Anti-Black Racist

Lying in both the publicly accessible archives of the South African state records in Pretoria and in the Johannesburg public library are full sets of the newspaper which Gandhi started in that country: the Indian Opinion. In addition, the Indian government has built an Internet site dedicated to Gandhi, and much of his writing is now available online as well. From these, and the official compilation of Gandhi’s writings, the Collected Works, the true face of Gandhi emerges: an anti-Black Indian racist!

“The Raw Kaffir” – Gandhi Describing the Blacks

When Gandhi addressed a public meeting in Bombay on September 26, 1896, he had the following to say about the Indian struggle in South Africa:[1]

“Ours is one continued struggle against degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the European, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir, whose occupation is hunting and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with, and then pass his life in indolence and nakedness.”

In 1904, opposing the then white British South African government’s plan to draw up a register of all non-Whites in the urban areas, Gandhi wrote about natives who do not work:[2]

“It is one thing to register natives who would not work, and whom it is very difficult to find out if they absent themselves, but it is another thing -and most insulting – to expect decent, hard-working, and respectable Indians, whose only fault is that they work too much, to have themselves registered and carry with them registration badges.”

Commenting on a piece of legislation planned by the white Natal Municipal authority, called the Natal Municipal Corporation Bill, Gandhi wrote in his newspaper, the Indian Opinion, on March 18, 1905:[3]

“Clause 200 makes provision for registration of persons belonging to uncivilized races, resident and employed within the Borough. One can understand the necessity of registration of Kaffirs who will not work, but why should registration be required for indentured Indians who have become free, and for their descendants about whom the general complaint is that they work too much?”

“The Native – Little Benefit to the State” – Gandhi

The Indian Opinion published an editorial on September 9, 1905, under the heading “The relative Value of the Natives and the Indians in Natal.” In it, Gandhi referred to a speech made by Rev. Dube, an early African nationalist, who said that an African had the capacity for improvement, if only the Whites would give them the opportunity. In his response, Gandhi suggested:[4]

“A little judicious extra taxation would do no harm; in the majority of cases it compels the native to work for at least a few days a year.”

Then he added:[4]

“Now let us turn our attention to another and entirely unrepresented community – the Indian. He is in striking contrast with the native. While the native has been of little benefit to the State, it owes its prosperity largely to the Indians. While native loafers abound on every side, that species of humanity is almost unknown among Indians here.”

Gandhi Complained about British Use of “Kaffir Police”

In a letter to the editor of the Times of London, published on November 12, 1906. Gandhi complained that under British rule, “Kaffir police” were “hustling” Indians in South Africa. Gandhi wrote:[5]

“Poor people were, under the registration effected by Lord Milner’s advice, dragged at four o’clock on a cold winter’s morning from their beds in Johannesburg, Heidelberg and Potchefstroom, and marched to the police station, or Asiatic Offices, as the case might be. It is they who under the Ordinance would be hustled by the Kaffir Police at every turn, and not the better-class Indians.”

Gandhi’s opinion of a series of 1906 amendments to the “Asiatic Law,” No. 3 of 1885, which placed certain restrictions upon Indians in British South Africa, are also insightful as to his true views on race. Writing in his Indian Opinion newspaper on 8 June 1907, Gandhi remarked that that the law “does not apply to Kaffirs and Cape Boys”[6] and went on to write that one of the main concerns he had with the act, which he called an “obnoxious law,” was that a “Kaffir police constable” could detain an Indian. He wrote:[6]

“At present, only the Permit Secretary is authorized to inspect a permit. Under the new Act, every Kaffir police constable can do so. Under the new Act, a Kaffir police constable can ask [an Asiatic] for particulars of name and identity, and, if not satisfied, can take him to the police station.”

After dealing with a number of other grievances with the law, Gandhi added:[6]

“Is there any Indian who is not roused to fury by such a law? We should very much like to know the Indian whose blood does not boil. And it is incredible to us that any Indian may want to submit to such legislation.”

Gandhi’s Role in the Bambetta Uprising

In 1906, a Zulu rebellion against British rule took place in the colony of Natal. His alleged pacifist ideals notwithstanding, Gandhi joined up with the British forces and became an ambulance stretcher bearer, helping to suppress the Black rebellion, known as the Bambetta Uprising. In his memoirs of the campaign to help the British defeat the Blacks, Gandhi wrote of how he saw a “Kaffir who did not wear the loyal badge” – i.e., a Zulu who was not loyal to the British and who had taken part in the uprising against the White British colonial rule.[7]

“As we were struggling along, we met a Kaffir who did not wear the loyal badge. He was armed with an assegai and was hiding himself. However, we safely rejoined the troops on the further hill, whilst they were sweeping with their carbines the bushes below.”

Gandhi also remarked on how unreliable these “loyal” Blacks were:[7]

“The Natives in our hands proved to be most unreliable and obstinate. Without constant attention, they would as soon have dropped the wounded man as not, and they seemed to bestow no care on their suffering countryman.”

The most poignant line in Gandhi’s Zulu war memoirs is however this one, which exposes his alleged pacifism as a hoax:[7]

“However, at about 12 o’clock we finished the day’s journey, with no Kaffirs to fight.”

Contrary to the liberal myth, Gandhi never once tried to help anybody else but Indians, and even then, only upper casts Indians at that. He consistently sought a special position for his people which would be separated from and superior to that of the Blacks.[8]

A good example came when the British colony of Natal took active steps to ensure that the Indians in that colony were deprived of the vote. “The Franchise Amendment Bill,” introduced in 1896, prohibited Indians from registering for the vote, while allowing those already on the rolls to remain. Within a few years, this eliminated the Indian as a voting factor in Natal, and it was this law that caused the Indian merchants to ask Gandhi to stay in South Africa, and against it was established the Natal Indian Congress, the first Indian political organization in South Africa. One of the first achievements of the Natal Indian Congress – which Gandhi established – was the creation of a third separate entrance to the Durban Post Office. The first was for Whites, but previously Indians had to share the second with the Blacks. The third entrance – for Indians alone – satisfied Gandhi.[8]

“Indian Ranked Lower than the Rawest Native”

In their petitions against the Natal franchise bill, the Indians, with Gandhi as their spokesman, complained that “the Bill would rank the Indian lower than the rawest Native.” In attempting to protect their own position, they believed they had to separate themselves from the native Blacks.[8] In addition, other prominent Indians, all colleagues of Gandhi, frequently complained of being mixed in with Natives in railway cars, lavatories, pass laws, and in other regulations.[8] Recalling his time in a Transvaal prison in October 1908, Gandhi said later that he spent the “first night in the company of some Kaffir criminals, wild-looking, murderous, vicious, lewd and uncouth.”[9]

Gandhi and Race

Gandhi was, despite modern propaganda, acutely aware of the differences between races, as this letter to W.T. Stead, an English friend of his in London, written in 1906, clearly shows:[10]

“As you were good enough to show very great sympathy with the cause of British Indians in the Transvaal, may I suggest your using your influence with the Boer leaders in the Transvaal? I feel certain that they did not share the same prejudice against British Indians as against the Kaffir races but as the prejudice against Kaffir races in a strong form was in existence in the Transvaal at the time when the British Indians immigrated there, the latter were immediately lumped together with the Kaffir races and described under the generic term ‘Coloured people’. Gradually the Boer mind was habituated to this qualification and it refused to recognize the evident and sharp distinctions that undoubtedly exist between British Indians and the Kaffir races in South Africa.”

Indeed, Gandhi remarked about the issue of taxation of Indians in South Africa that “A Kaffir is to be taxed because he does not work enough: an Indian is to be taxed because he works too much.”[11] Writing about a law which was designed to restrict Indian movement in the British Cape Colony, Gandhi objected on the basis that it dragged Indians “down with the Kaffir[s].” He wrote:[12]

“The bye-law has its origin in the alleged or real, impudent and, in some cases, indecent behaviour of the Kaffirs. But, whatever the charges are against the British Indians, no one has ever whispered that the Indians behave otherwise than as decent men. But, as it is the wont in this part of the world, they have been dragged down with the Kaffir without the slightest justification.”

Gandhi Was Aware of the Abusive Nature of his Words

In what context did Gandhi use this word “Kaffir,” which is most certainly a term of abuse? Gandhi himself understood full well the word’s meaning. He himself commented in later life as follows when commenting upon another person’s use of the word to describe a Christian:[13]

“And finally, about Mr. Douglas who, as I have stated above, has tendered his resignation. The gentleman has been simply overhasty. He took offence at the Maulana Saheb’s use of the word kaffir for a Christian. I can understand his resentment. It would have been better if the word kaffir were not used.”

In addition, Gandhi remarked “If Kaffir is a term of opprobrium, how much more so is Chandal?” referring to Hindu and Muslim slang words for each other.[14] Therefore there can be little doubt as to Gandhi’s racist intention when he referred to “Kaffirs” in South Africa, and only a deluded liberal would suggest otherwise.

“The Prominent Race”

In the Government Gazette of Natal for Feb. 28 1905, a Bill was published regulating the use of fire-arms by Blacks and Indians. Commenting on the Bill, Gandhi wrote in his newspaper, the Indian Opinion on March 25, 1905:[15]

“In this instance of the fire-arms, the Asiatic has been most improperly bracketed with the natives. The British Indian does not need any such restrictions as are imposed by the Bill on the natives regarding the carrying of fire-arms. The prominent race can remain so by preventing the native from arming himself. Is there a slightest vestige of justification for so preventing the British Indian?”

Gandhi, like many caste-conscious Indians (he was born to a fairly high shop-owner caste) was all in favor of segregation from the Blacks. His reaction to a petition to the King launched by non-Whites in South Africa in 1906, demanding voting rights, reveals this attitude clearly:[16]

“It seems that the petition is being widely circulated, and signatures are being taken of all colored people in the three colonies named. The petition is non-Indian in character, although British Indians, being colored people, are very largely affected by it. We consider that it was a wise policy on the part of the British Indians throughout South Africa, to have kept themselves apart and distinct from the other colored communities in this country.”

The Famous Train Incident

In the Hollywood film made about Gandhi, much emphasis was placed on a scene where he was arrested for riding in a South African railroad coach reserved for Whites. This incident did indeed occur, but for very different reasons than those the film portrayed! For the liberal myth is that Gandhi was protesting at the exclusion of non-Whites from the railroad coach: in fact, he was trying to persuade the authorities to let ONLY upper caste Indians ride with the Whites.

It was never Gandhi’s intention to let Blacks, or even lower-caste Indians, share the White compartment! Here, in Gandhi’s own words, are his comments on this famous incident, complete with reference to upper-caste Indians, whom he differentiated from lower-caste Indians by calling the former “clean”:[17]

“You say that the magistrate’s decision is unsatisfactory because it would enable a person, however unclean, to travel by a tram, and that even the Kaffirs would be able to do so. But the magistrate’s decision is quite different. The Court declared that the Kaffirs have no legal right to travel by tram. And according to tram regulations, those in an unclean dress or in a drunken state are prohibited from boarding a tram. Thanks to the Court’s decision, only clean Indians or colored people other than Kaffirs, can now travel in the trams.”

Gandhi Supported Segregation

It is also a myth to presume that Gandhi was opposed to racial segregation. Witness this piece of his writing, published in his newspaper, Indian Opinion, of February 15, 1905. It was a letter to the white Johannesburg Medical Officer of Health, a Dr. Porter, concerning the fact that Blacks had been allowed to settle in an Indian residential area:[18]

“Why, of all places in Johannesburg, the Indian location should be chosen for dumping down all Kaffirs of the town, passes my comprehension. Of course, under my suggestion, the Town Council must withdraw the Kaffirs from the Location. About this mixing of the Kaffirs with the Indians I must confess I feel most strongly. I think it is very unfair to the Indian population, and it is an undue tax on even the proverbial patience of my countrymen.”

Gandhi’s Support for “Purity of Race”

In response to the rise of white nationalist politics, which stressed racial separation, Gandhi wrote in his Indian Opinion of September 24, 1903:[19]

“We believe as much in the purity of race as we think they do, only we believe that they would best serve these interests, which are as dear to us as to them, by advocating the purity of all races, and not one alone. We believe also that the white race of South Africa should be the predominating race.”

On December 24, 1903, Gandhi added this in his Indian Opinion newspaper:[20]

“The petition dwells upon `the co-mingling of the colored and white races.’ May we inform the members of the Conference that so far as British Indians are concerned, such a thing is particularly unknown. If there is one thing which the Indian cherishes more than any other, it is the purity of type.”

And yet the liberal delusion over Gandhi lives on!

Notes

| [1] | The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Ahmedabad, 1963, Volume II p. 74 |

| [2] | Ibid., Volume IV p. 193 |

| [3] | MK Gandhi, Indian Opinion, March 18, 1905 |

| [4] | Ibid., September 9, 1905 |

| [5] | MK Gandhi, Letter to The Times, London, November 12, 1906, as reproduced on ‘The Complete Site on Mathatma Gandhi,’ http://www.mkgandhi.org/cwm/vol6/ch060.htm |

| [6] | MK Gandhi, Indian Opinion, June 8, 1907, ‘New Obnoxious Law’, as reproduced at ‘The Complete Site on Mathatma Gandhi,’ http://www.mkgandhi.org/cwm/vol6/ch409.htm |

| [7] | MK Gandhi, “Memoirs of the Indian Stretcher Bearer Corps,” as published in Indian Opinion, July 28, 1906, and reproduced on ‘The Complete Site on Mathatma Gandhi,’ http://www.mkgandhi.org/cwm/vol5/ch262.htm |

| [8] | James D. Hunt, Gandhi and the Black People of South Africa, Shaw University, and reproduced on ‘The Complete Site on Mathatma Gandhi,’ http://www.mkgandhi.org/articles/jamesdhunt.htm |

| [9] | B. R. Nanda, Mahatma Gandhi – A Biography, page 105, The Official Mahatma Gandhi eArchive, Mahatma Gandhi Foundation – India, http://www.mahatma.org.in/books/showbook.jsp?link=og&book=og0003&id=105&lang=en&file=3418&cat=books |

| [10] | MK Gandhi, Letter to W.T. Stead, London, November 16, 1906, from a photostat of the typewritten office copy: S.N. 4584, as reproduced at ‘The Complete Site on Mathatma Gandhi,’ http://www.mkgandhi.org/cwm/vol6/ch092.htm |

| [11] | MK Gandhi, The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, Volume III, page 337, The Official Mahatma Gandhi eArchive, Mahatma Gandhi Foundation – India, http://www.mahatma.org.in/books/showbook.jsp?link=bg&book=bg0015&id=358&lang=en&file=1750&cat=books |

| [12] | Ibid., page 285, The Official Mahatma Gandhi eArchive, Mahatma Gandhi Foundation – India, http://www.mahatma.org.in/books/showbook.jsp?link=bg&book=bg0015&id=306&lang=en&file=1698&cat=books |

| [13] | Mahadev Desai, Day to day with Gandhi, Volume II, page 291, The Official Mahatma Gandhi eArchive, Mahatma Gandhi Foundation – India, http://www.mahatma.org.in/books/showbook.jsp?link=bg&book=bg0015&id=36&lang=en&file=1428&cat=books |

| [14] | MK Gandhi, The Hindu-Muslim Unity, page 45, The Official Mahatma Gandhi eArchive, Mahatma Gandhi Foundation – India, http://www.mahatma.org.in/books/showbook.jsp?link=bg&book=bg0020&id=61&lang=en&file=7426&cat=books |

| [15] | MK Gandhi, Indian Opinion, March 25, 1905 |

| [16] | Ibid., March 24, 1906 |

| [17] | Ibid., June 2, 1906 |

| [18] | Ibid., February 15, 1905 |

| [19] | Ibid., September 24, 1903 |

| [20] | Ibid., December 24, 1903 |

Bibliographic information about this document: The Revisionist 2(2) (2004), pp. 184-186

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a