“There is a Certain People in Our Midst…”

In discussions of the famous/infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion, we often hear reference to the age-old hatred of Jews, which date back at least as far as Haman in the Old Testament Book of Esther. According to the Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish religion, “[…] indeed, the expression of animosity toward the Jews is found as early as the Proclamation of Haman.”[1]

Jehuda T. Radday, Professor Emeritus for Jewish Studies at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa, is well positioned to enlighten us on this subject. He writes:[2]

“This is the first anti-Jewish pamphlet in Jewish history, and Jews wrote it as parody. Humor is one of the means by which Jews explain the limitless, to them inconceivable hatred of Jews. For example, in the Book of Esther they ascribe a circular letter to Haman, who was the very incorporation of anti Semitism. Haman’s letter contains almost everything that is to be found in later, similar decrees: condemnation of Jewish godlessness, ingratitude, greed, wizardry, cruelty and exploitation of their fellow man, along with a determination to finally deal with the Jewish Problem. […] The humor in the Book of Esther is unmistakable.”

The condemned German “war criminals” found little to laugh about in the Nuremberg Military Tribunal in 1945, however, when they learned that their deaths had been foretold in the Book of Esther:[3]

“In recounting the ten names of the sons of Haman, several letters are traditionally written small; according to rabbinical hermeneutics, this is done deliberately for the sake of emphasis. The first son was called Parschandata, a name which can be taken as an added incentive to puzzle out this given name, since ‘parschan data’ means the ‘interpretation of religion.’ The small letters in the other names: Schin, Tet, Sajin give the date of 5707 after Creation, which is exactly the year of the Nuremberg executions. Thus, this Happy Ending was foretold in the Bible.”

We ask ourselves why Prof. Radday interprets a historical event which occurred 2400 years ago and, according to the Bible, cost the lives of at least 75,000 persons, and whose continuation in history has had such gruesome consequences, as simple humorous parody. The answer is simple. Concerning Haman, the Jewish Lexicon states quite succinctly that “[…] this figure is no more historical than the rest of the story of Esther.”[4]

From the Book of Esther: Haman and his Ten Sons on the Gallows.

In our study of “Semitism” and “Anti Semitism,” let us recreate the Haman proclamation in this remarkable roman a cléf. Chapter 3, verses 12-13, of the Book of Esther tells the story of the government minister Haman, who is reporting to his king Ahasueros about the perfidy of the Jews. Ahasueros’ Persian name was Xerxes I, and he ruled from 486 to 465. On Xerxes’ authority Haman commanded that a letter be written to all the princes and landowners, admonishing them to exterminate the Jews and expropriate their possessions:[5]

“To all peoples, nations and languages, may your fortunes blossom and grow! May it be made known to you that a certain man has appeared before us who comes not from our midst and our empire but rather from Amalek, who is of high blood and named Haman, and requests a small kindness from us. There is a certain nation in our midst which is more despicable than all others. Its people are arrogant, mockingly malicious, and given to despoliation and evil of every kind. Every evening, morning and afternoon, this nation curses our King with these words: ‘Our Lord is King forever, and the nations will perish from his land’ (Psalms 10:16.) This nation is ungrateful as well; just look what it has done to poor Pharaoh […]. Their conduct is still deplorable, and they make a joke of our religion. Therefore we have unanimously decided to destroy them. When this reaches you, be prepared to slay and annihilate all the Jews amongst us, young and old, women and children, all on a single day, and let not a single one of them escape alive!”

The suspicion of parody in the Book of Esther is not new.

As early as 1903, an article by Moritz Steinschneider appeared which was entitled “Purim and Parody.”[6] At about the same time, the following appeared in Meyers Großem Konversationslexikon [Meyers Expanded Encyclopedia]:[7]

“The improbabilities of this entire report are so great, the lust for vengeance so keen and so obviously inspiring for the writer, that even Luther objected to the book. It is a fact that the Book of Esther represents nothing except a legendary explanation for the development of the Purim festival. Its conception lies in the age of the Ptolemaians and Seleucids.”

In the last years of his life Luther concluded:[8]

“O how they love the Book of Esther which so appeals to their bloodthirsty, vengeful, murderous lust and hope. The sun never shone on a more bloodthirsty and vengeful nation than those who think that they are the People of God and therefore allowed to murder and strangle the heathen. And the crowning glory for them is that they expect their Messiah to murder and destroy the whole world.”

The Encyclopedia Judaica, published in Jerusalem in 1971, under the heading “Scroll of Esther,” No. 1051, reports:[9]

“Nevertheless, accepting Esther as veritable history involves many chronological and historical difficulties.”

Gershom Scholem

For example, Mordechai would have to have been more than 100 years old. Furthermore, Herodotus had already noted that the Queen was named Amestris and not Esther or Bashti (her predecessor), etc. An important group of researchers consider both the Book of Esther as well as the Book of Daniel to be pseudo-epigraphy. Spinoza was of the opinion that the Books of Daniel, Esra, Esther and Nehemia were all written by the same historian and therefore not original.[10] Abba Eban, the former Israeli prime minister, acknowledged this as well:[11]

“One of the difficulties which the historian encounters in writing the history of the Jews is silence in the historiographies of other nations.”

In Die Entstehung des Alten Testaments (The Evolution of the Old Testament), the standard reference work on the Old Testament, written by Rudolf Smend of Göttingen, we read:[12]

“[…] this gripping tale, conceived and written with great skill, has a very twisted relationship to historical reality. It is wasted effort to search for a ‘historical nucleus,’ aside from the general predicament of the Jews in the Diaspora. […] Therefore, we can safely assume that the author is reworking older material.”

In Hans Schmoldt’s Kleinen Lexikon der biblischen Eigennamen (Abridged Encyclopedia of Biblical Names,) we read:[13]

“The Ester figure is not historical. We are dealing with a novella having strong national tendencies, written in the second or third century BC.”

Leo Trepp too is of the opinion that[14]

“[…] it can not be historically determined whether this event really took place or not. However, the fundamental attitude which speaks to us from the story serves as an inspiration to everyone.”

He disregards the alleged slaughter of more than 75,000 persons.

Chaim Cohen, author of the “Esther” article in The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion (1997) is likewise compelled to admit:[15]

“[…] the purpose of including historically accurate elements must have been to provide Esther with an authentic historical background; thus Esther can be categorized as a historical novella.”

An event such as the slaughter of 75,000 countrymen would have to have found notation in the historiography and collective consciousness of the Persians, if there is such a thing. This apparently is not the case, as my Iranian colleague in Berlin assures me. Other stories constituting Jewish identity, such as the Exodus from Egypt, should likewise be considered pure myth. In the opinion of the Egyptologist Jan Assman:[16]

“Here we are dealing with a myth whose authenticity consists less of historical than spiritual reality.”

This is perhaps the most elegant explanation. In the course of a Max Horkheimer lecture at the Goethe University in Frankfurt, the Israeli philosopher Avishai Margalit spoke about the “Ethik des Gedächtnisses” (Ethics of Remembrance). Ritual ethical remembrance takes place when the object of memory is not only in the distant past, but probably never existed. Examples of this are the myths of Zero Hour, the Exodus, the Sovereign Will expressed by the Presentation of the Ten Commandments, the Original Sacrifice, Founding Hero, etc.[17]

The correspondent of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung in Israel, Jörg Bremer, reports:[18]

“The sagas of the Hebrews and Israelites were formed into the present Codex during the Babylonian Exile in the 6th Century BC. Almost certainly, the authors of the Codex were priests who were attempting to protect and retain their congregations for Jahwe from assimilation. They needed Abraham and Moses, David and Solomon in order to found the Temple and Tora theologically. Their intention was not to recount history, but to consolidate their religious communities.”

Pseudo-Epigraphy

This phenomenon is known as pseudo-epigraphy and is defined as a “body of writing which is mistakenly ascribed to a given author.” (pseudo = not genuine; epigraphy = inscription.) From the religious philosopher and Cabala researcher Gershom Scholem we learn:[19]

“Pseudo-epigraphy is a well known category in the history of religious literature. There have always been authors who composed works that were allegedly authored by ancient masters or else created by divinely inspired persons […]. Nearly all the apocalyptical Midraschim are pseudoepigraphs of this type.”

The same is true of the works of Jewish mysticism, according to Jacob Hessing:[20]

“Mose de Leon represented the Zohar,[21] which he himself had written, as an ancient work from primeval times. It was not until quite recently that modern research was able to discover the real subject matter. He wanted to give his work the nimbus of a primeval presence of God, and probably did not have complete confidence in his own theosophical speculations.”

Feedback

Exegesis (critical interpretation) of texts then amplifies the significance of the pseudoepigraphical “primeval texts.” As Johann Meier explains:[22]

“The Cabalistic significance of the Tora strengthened traditional basic assumptions, and so, for the Cabalists, the Tora became the revelatory key to understanding everything, even the Godhead.”

In 1792, Salomon Maimon recalled in his autobiography:[23]

“One grasped the most remote analogies between signs and things, until finally the Cabala culminated in a systematic body of knowledge which raged against Reason or relied on absurd notions.”

This is this way that “Welten aus dem Nichts” (Worlds Out of Nothing) evolved.[24] In the Lexikon exegetischer Fachbegriffe (Encyclopedia of Exegetic Expert Terms) we read:[25]

“One should not consider biblical pseudo-epigraphy negatively, as deceitful fiction created by its writers, but rather positively, as an extension of the authority of an apostle or follower. We are dealing with intentional preservation and adaptation of a particular tradition, rather than a simple falsification or imitation.”

According to H. Gunkel, ancient Israel treated a lie much less severely than we do. If no shameful intentions were connected with a lie, then there was nothing dishonorable connected with it.[26] Even the philosopher Adolf von Harnack found:[27]

“One cannot rely on Jewish sources and as a rule, the same is true of learned Jews.”

In Heinrich Heine we learn:[28]

“When Luther declared that his teachings could be contradicted only by the Bible itself or on rational grounds, human reason was empowered to explicate the Bible. Reason was thenceforth acknowledged to be the highest authority in judging all points of religious contention. In Germany, this developed into so called Geistesfreiheit [Freedom of the Spirit] or Denkfreiheit [Freedom of Thought] as it is also called.”

According to Rudolf Smend:[29]

“For 300 years now, the Bible has been the object of an ever growing critique. This critique was often, but not always, a part of the critique of the Christian faith; it shocked entire generations with its negative utterances and proofs. The so called ‘Five Books of Moses’ were not written by Moses; the Psalms were not written by David; and the messianic prophesies for the most part are hardly compatible with Jesus. Of the four gospels, not a single one was written by an apostle. And only a portion of the letters which were specifically attributed to Paul really originated with him.”

Such realizations, however, do not discourage the exegete (person who critically interprets obscure texts.) The exegete believes that biblical criticism has produced positive as well as negative results. This has been accomplished through the study of[30]

“[…] how biblical texts have evolved and developed. It has caused the Bible to become a living book in an entirely new way; in other words, a human book. But how does that comply with the requirement that God’s word be here among us? Mustn’t that finally be abandoned as outmoded concept? Many people do in fact believe this to be true, but this is the result of misunderstanding. The more familiar we become with the Bible in its radical and overall humanity, the more we also perceive that the Bible is and ever will be complete witness to the actions and message of God. God is not directly tangible in the Bible, or else He would not be God. The conflicting testimony which He gives through the men who wrote the Bible is sometimes so self contradictory that it becomes the very opposite of itself. However, the men who wrote the Bible all agree: they all speak to us on His behalf and they all commune with Him as well.”

To take a written text of which almost nothing is authentic, and then make an authentic text of it, requires genuine dialectical abilities! Georg Christoph Lichtenberg poked fun at this when he wrote:[31]

“One thing is certain: the Christian religion is more challenged by those who earn their bread by it than by those who are convinced of its veracity.”

The essential clues to understanding the Haman letter are the parodistic criticisms leveled by the Jews against themselves, which correspond essentially to other nations’ actual criticisms of Jews. These were quite common in ancient times, for example in Cicero, Diodoros, Hekataios, Justinius, Jevanalis, Persius, Quintilianus, Seneca, Suetonius, Tacitus and Tertullianus. Such criticisms even appear in the Old Testament. If this letter of Haman served as a pattern for the later polemics against Jews, as Prof. Radday believes, then it is certainly not unreasonable to treat the famous/infamous Protocols as a work created by Jewish hands, even though such conversations in the form of actual protocol did not actually take place.

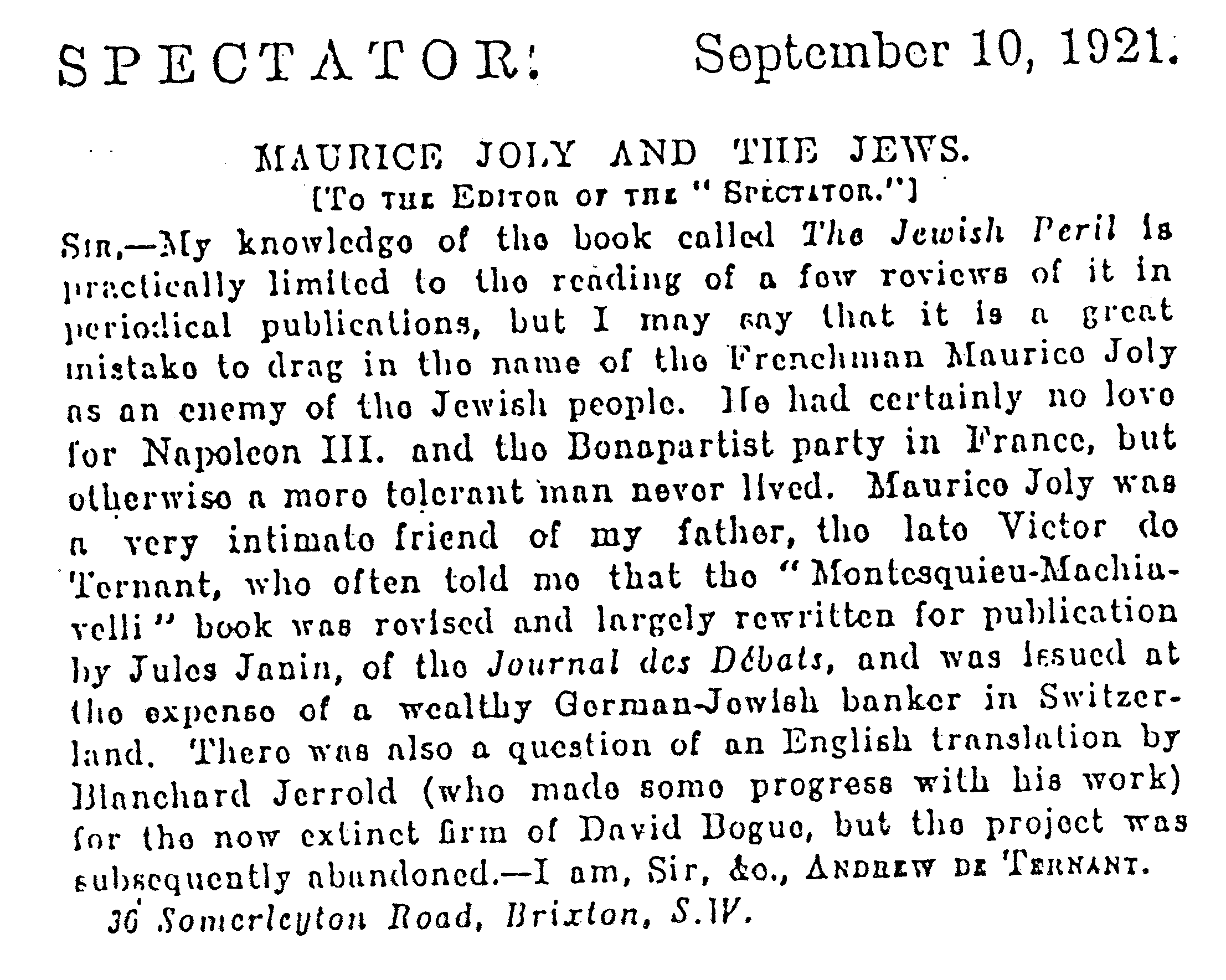

An interesting letter from a reader concerning the Protocols.

This thesis is found in one of the most recent works on this subject by Stephen Eric Bronner, Ein Gerücht über die Juden (A Rumor about Jews):[32]

“The Protocols of the Elders of Zion represent one of the most infamous documents of anti Semitism. The document allegedly deals with the record of twenty-four sittings of a congress of representatives of the ‘Twelve Tribes of Israel’ who come together under the leadership of a leading rabbi in order to plot the conquest of the world. This congress never took place […]. What the real Communist Manifesto was for Marxism, the fictitious Protocol represents for anti Semitism. They made it possible for anti-Semites to identify the Jews as their nemesis and to envision an element dwelling within Western civilization as their antithesis. This anthropological view does in fact prepare the way for the theory expressed in the pamphlet […]. Behind the countless forms of hatred toward the Jews lies the continuity of prejudice.”

Isn’t this exactly what Radday says about Haman’s letter, the first fictitious document that the Jews introduced as parody? This would presumably be a new kind of “conspiracy theory” – that the Prococols were both authentic and spurious at the same time, corresponding to the Jewish inclination to paradox. Perhaps it is significant that although the Protocols were once banned in Russia, one can buy them today in Germany – and from a leftist publishing house.[33] This is a measure of official confidence in the protective effect of the “conspiracy theory” weapon.

Authors who attempt to unmask the Protocols as counterfeit are fond of pointing out that important passages were plagiarized from a polemic directed against Napoleon III in 1865. Written in 1865 by Maurice Joly, it was said to be anti-Semitic. “A Quarrel in Hell – Conversations between Machiavelli and Montesquieu Concerning Power and Justice” was republished in German in 1990 in a new edition, by Hans Magnus Enzensberger of the leftist Eichborn Publishing House. The original text was entitled Dialogue aux enfers. From a letter to the editor of Spectator in the September 10, 1921, issue, written by a certain Andrew de Ternant, we perceive that Ternant’s father had been a close friend of Joly, and that publication of the book was commissioned by a German Jewish banker living in Switzerland. Such revelations usually have little effect, however. Whoever grants them the slightest acknowledgement is viewed as an anti-Semite, or at least labeled an apologist for pogroms, since:[34]

“Basically, conspiracy theories belong to contemporary forms of Jew-hating. Today, anti-Semitism casts its black shadow upon all discussion of conspiracy.”

A beneficial result of the Protocols, which have brought the Jews so much deserved or undeserved notoriety, has been to provide them “ethnic or religious profiling, which contributes to self assertion.” This helps maintain Jewish uniqueness during times when tensions are absent and “[…] assimilation, in the absence of problematic circumstances,” becomes the greatest danger. Such is the conclusion of the series of articles Judentum und Umwelt (Judaism and the Environment) published by Johann Maier. It is an interesting way to view the problem which Jews have in their dealings with others.

Just as the “fascism club” is used to stifle criticism of the Jews, according to Hans Helmut Knütter, the Protocols are likewise used in the form of a “conspiracy-theory-club” to silence critics. The mere mention of “conspiracy” denies expression to the speaker. One needs only mention that this or that is written in the Protocols to evoke the automatic response that they were long ago unmasked as a counterfeit and are furthermore “anti-Semitic.” In the lee of this rhetorical protective umbrella, the incriminated Jewish program can then be realized one way or another. The ever-recurrent reports about the unsavory history of the Protocols and attendant dire consequences strengthen the protective mechanism. We can think of it as a kind of “tele-lobotomy,” remote suppression of part of our intellectual apparatus. “Islands of paralysis of our thought and judgment” then develop, as Mathilde Ludendorff describes them in Fortführung der Erkenntnisse des Psychiaters Kräpelin (Continuation of the Discoveries of Psychiatrist Kräpelin.)[35]

This method of Jewish attack, like the charge of “fascism,” can not be countered. Whoever attempts to confront it, quickly realizes that he is already indicted and convicted. Referral to psychiatric treatment is a distinct possibility, as Martin Blumentritt illustrates:[36]

“If for example a person were obsessed with the fixed idea that all red-haired waiters were trying to kill him, that person would surely be referred to a psychiatrist. This insane idea is psychologically no different from the insane notion of a Jewish world conspiracy.”

For Blumentritt, enlightenment means the disappearance of prejudice; needless to say, he considers anti Semitism prejudice. This makes deployment of the protective screen both invisible and unnamable. Jews, in his view, are naturally free of prejudice; insofar as Jews are not free of prejudice, they are victims of “Jewish self hate.” However, Blumentritt reveals a dark premonition that “[…] the conceit that one is free of prejudice is the most persistent conceit of all.”[37]

“Jews who are mesmerized by the magic of tradition, or else have found their way back to it, consider the efforts of the historian to be quite irrelevant. For them, the important thing about the past is not its historicity, but its eternal presence. If a given text engages them, the question of its derivation is of secondary importance to them, if not completely meaningless. Today, many Jews are searching for a past, but they obviously do not accept the past which the historian has to offer […]. The ‘Holocaust’ has already prompted more historical research than any other event in Jewish history. However, the shape of this event was obviously formed not on the anvil of the historian, but rather in the melting pot of the fiction writer. Much has changed since the 16th century, but one thing, strangely enough, has remained the same: Jews are still not prepared to subject themselves to history (in those cases where they do not completely reject history.) They prefer to wait for a new meta-historical myth. In the meantime (at least for the present), fiction can be used as a modern surrogate for this metahistorical myth.”

We hope we are allowed to quote the above; after all, it was printed by a leftist publisher.

Officially sanctioned, politically correct historiography is playing a curious game of hide-and-seek with its fictitious surrogate. We read the following in the universally acclaimed Jewish philosopher Yeshajahu Leibowitz, author of Selbstkritik des Judentums auf Höchstem Niveau (Self Criticism of Judaism on the Highest Level),[38] who died in 1994:[39]

“We can say with considerable certainty that, without Hitler, the Third Reich would never have come about. Therefore, Adolf Hitler is the greatest personality in the history of mankind.”

Whoever would have thought it?!

Editor’s Comment

As a German author, Manon focusses on foreign, especially German scholars and ignores English-writings. Hence I may add here: Manon’s judgment was also made more recently by John Lukacs in The Hitler of History (Knopf, New York 1998). Douglas Reed, in The Controversy of Zion, points out that the Nuremberg “criminals” were hanged on Purim, the Day of Judgment; this remarkable fact is left out by Manon.

Notes

First published as “Ein Volk gibt es unter uns…,” in Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung 5(2) (2001), pp. 205-209; translated by James M. Damon.

| [1] | “Indeed, the expression of animosity toward the Jews is found as early as the statement of Haman: ‘There is a certain people…’ “ (see Werblowsky/Wigoder: “Anti Semitism,” p. 53). |

| [2] | Jehuda T. Radday, Magdalena Schultz (Editors), Auf den Spuren der Parascha – Ein Stück Tora – Zum Lernen des Wochenabschnitts, [On the Trail of the parascha – A Portion of the Tora –- Learning the Weekly Segments] Diesterweg, Frankfurt am Main / Sauerländer, Aarau / Institut Kirche und Judentum, Berlin 1989 Arbeitsmappe 2. |

| [3] | Daniel Krochmalnik in: Landesverband Bayern der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinden, March 1995, p. 5. |

| [4] | Jüdisches Lexikon, 1927, p. 1370. |

| [5] | The Hamán Letter, Esther 3, 12-13, according to Y. T. Radday, Auf den Spuren der Parascha (On the Trail of the Parascha) Vol. 1, 1989. For those who do not have the Holy Scriptures, Erich Glagau has recounted the entire story in Eine Königin läßt morden. Ein biblischer Kriminalroman [A Queen Orders Murder Be Done, A Biblical Mystery] published by Werner Symanek, Bingen am Rhein, 1994. |

| [6] | MGWJ – Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums, Breslau, No. 47, pp. 283-286. |

| [7] | Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon, 6. Bd., S. 128. |

| [8] | Ausgewählte Werke (Selected Works), Chr. Kaiser, München 1936, Vol. III, p. 81. |

| [9] | “Nevertheless, accepting Esther as veritable history involves many chronological and historical difficulties.” |

| [10] | Carl Gebhardt, Günter Gawlick (Hg.), Sämtliche Werke [Collected Works], Felix Meiner, Hamburg 1994, Vol. III, p. 177. |

| [11] | Das Erbe – Die Geschichte des Judentums [The History of Judaism], Ullstein, Frankfurt am Main/Berlin 1986, S. 35. |

| [12] | 4th Edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1978, p. 221. |

| [13] | Reclam, Stuttgart 1990, p. 73. |

| [14] | Leo Trepp, Die Juden – Volk, Geschichte, Religion [The Jews – Nation, History, Religion], Rowohlt, Reinbek 1998, p. 364. |

| [15] | “The purpose of including historically accurate elements must have been to provide Esther with an authentic historical background; thus Esther can be categorized as a historical novella.” (p. 236) |

| [16] | Politische Theologie zwischen Ägypten und Israel [Political Theology Between Egypt and Israel], Carl Friedrich von Siemens Foundation, München 1992, p. 110. |

| [17] | According to Jürgen Kaube: “Mit Lücken” [With Gaps] in: FAZ (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung), May 26, 1999, p. N5. |

| [18] | “Kein Platz für Christi Stellvertreter” [No Place for a Vicar of Christ] in: FAZ, 18 March 2000, p. I. |

| [19] | Sabbatai Zwi – Der mystische Messias (The Mystical Messiah), 1st Edition, Jüdischer Verlag (Jewish Publishing House,) Frankfurt a. M. 1992, p. 262. |

| [20] | Talmud und Kabbalah [Talmud and Cabala] in Jüdische Rundschau Maccabi, 12 Sept. 1996, p. 23. |

| [21] | Sefer ha-Zohar, Buch des Glanzes [Book of Radiance], principal work of the Cabala, traditionally ascribed to Simon ben Jochai (first half of second century AD.) Modern research, of which Scholem has done the most important part, discusses ascription of the book, especially its main part, to Mose ben Schem Tov de Leon (gest. 1305). This is according to Scholem in Judaica, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a. M. 1997, Vol. 6, p. 59, footnote 12. Following the First World War , Scholem acquired, in a Munich antique shop, a copy in French translation. The publisher, Jean de Pauly, allegedly an Albanian noble, but according to Scholem a converted Jew from East Galicia, had attempted to inject Christian dogma into the text. To the translation was added an appendix of almost a hundred pages which, as Scholem discovered, contained invented quotations from beginning to end. The translator was a master inventor and pathological swindler. Gershom Scholem, Von Berlin nach Jerusalem, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt a.M. 1997, pp. 138f. |

| [22] | The Cabbala, C. H. Beck, München 1995, according to Jakob Hessing, “Talmud und Kabbalah” [Talmud and Cabbala] in: Jüdische Rundschau Maccabi, 12 September 1996, p. 23. |

| [23] | Union, Berlin 1988, p. 76 |

| [24] | Jüdisches Lexikon, 1927, “Religion, jüdische” [Religion, Jewish], column 1335. |

| [25] | Paul-Gerhard Müller, Katholisches Bibelwerk [Catholic Bible], Stuttgart 1985, p. 204. |

| [26] | Genesis; Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1917; according to Radday, Auf den Spuren…, Vol. 6, p. 35. |

| [27] | Lehrbuch der Dogmengeschichte [Manual of Dogma History]; according to Friedrich Niewöhner, “Das Halbe und das Ganze” (Half and Entirety), in: FAZ, 23 Feb 2000, p. N 5. |

| [28] | Die Luther-Bibel [The Luther Bible], CD-ROM, Directmedia, Berlin 2000, Introduction. |

| [29] | Rudolf Smend, Altes Testament christlich gepredigt [The Old Testament, Christian Interpretation], Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000, p. 108. |

| [30] | AaO., p. 108. |

| [31] | Sudelbücher, Frankfurt 1984, according to Karlheinz Deschner, Der gefälschte Glaube – Die wahren Hintergründe der kirchlichen Lehren [The Counterfeit Faith – The Real Background of Church Teachings]; 7th Edition., Heyne, Munich 1995. |

| [32] | Ein Gerücht über die Juden – Die “Protokolle der Weisen von Zion” und der alltägliche Anti Semitismus [A Rumor About Jews – “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and Everyday Anti Semitism], Propyläen/Ullstein, Berlin 1999, p. 9. |

| [33] | Jeffrey L. Sammons (Editor), Wallstein-Verlag, Göttingen 1998. |

| [34] | Michael Angele, “Der Feind ist maskiert und lauert überall – Verschwörungstheorien und der Wahn von der großen bösen Absicht” [The Enemy is Masked and Lying in Ambush Everywhere – Conspiracy Theories and the Myth of Evil Intent] in: FAZ, 3 August 2000, p. 50. |

| [35] | Induziertes Irresein durch Occultlehren[(Induced Insanity Through Occult Teachings], 1933; Hohe Warte, Pähl 1970; see. Hans Pedersen, “Das Loch in der Tür” [The Hole in the Door], VffG, 1(2) (1997), pp. 79-83. |

| [36] | Die politische Dimension von Vorurteilen [The Political Dimension of Prejudice], Adapted Internet Version of a Lecture “Vorurteil ohne Ende” [Endless Prejudice], Nov. 18, 1977 in Loccum, p. 5. |

| [37] | Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, Zachor: Erinnere Dich! – Jüdische Geschichte und jüdisches Gedächtnis [Zachor: Remember! – Jewish History and Jewish Remembrance], Publisher Klaus Wagenbach, Berlin 1996, pp. 102-104. |

| [38] | Rudolf Kreis, “Zur Beantwortung der Frage, ob Ernst Nolte oder Nietzsche mit dem Judentum ‘in die Irre’ ging” [Answer to the Question Whether Ernst Nolte or Nietzsche ‘lapsed into error’ Regarding Judaism] in: Aschkenas, Vol. 2, 1992, p. 307, note 99. |

| [39] | Gespräche über Gott und die Welt [Discussions About God and the World], Dvorah, Frankfurt am Main 1990, p. 210. |

Bibliographic information about this document: The Revisionist 3(1) (2005), pp. 51-57

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: First published as “Ein Volk gibt es unter uns...,” in "Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung," 5(2) (2001), pp. 205-209