Tree-felling at Treblinka

1. Introduction

It is commonly alleged that a small (approximately 14 hectares large) camp in eastern Poland, usually denoted Treblinka II, served as a “pure extermination camp” for Jews between the end of July 1942 and August 1943. It is further alleged that at this camp somewhere between 700,000 and 900,000 Jews were killed with engine exhaust fumes in gas chambers, and that until March 1943 the victims were buried in huge mass graves. After this date, the hundreds of thousands of buried bodies – at least 713,555 corpses – were allegedly disinterred and incinerated, together with thousands of “fresh” victims, on cremation grates made of concrete blocks and railway gauge with wood used as fuel.[1]

It has been pointed out by several revisionist historians, among them Mark Weber, Andrew Allen, Arnulf Neumaier, Jürgen Graf and Carlo Mattogno, that the alleged cremations would have required an immense amount of firewood which could not have been procured easily. There exists no documentation of transports of wood to Treblinka, by truck or train, and neither have eyewitnesses spoken of such transports. This implies that the firewood required for any cremation carried out at Treblinka would have to have been procured from forests in the vicinity of the camp. In the following article I will analyze the Jewish witness Richard Glazar’s account of tree-felling at Treblinka and compare it to relevant maps and aerial photographs as well as to what is known about the nature of the woods surrounding the former camps and the efficiency of wood-fuelled open air incineration.

2. The Testimony of Richard Glazar

2.1. Glazar’s Description of Tree-felling at Treblinka in 1943

Richard Glazar’s published account of his alleged experiences in Treblinka II, Trap with a Green Fence, was originally published in German in 1992.[2] In this book, Glazar has described the felling of trees for the purpose of fuel procurement for cremations as follows:

“To clear the woods around the perimeter of the camp – that’s our main task now. Felled trees are hauled into camp and chopped into firewood. As spring becomes summer without transports, the greatest concentration of activity in the first camp moves down to the grounds behind the Ukrainian barracks, to the lumberyard. Those of us from Barrack A work there, along with other commando units who had previously worked at the sorting site. Idyllic mounds of freshly sawn and split firewood grow up and shine out from among the towering pines that have not been felled. A path runs along one side of the lumberyard and leads up to the main gate of the second camp. Though it is some seventy meters away, the gate is clearly visible from our work site. Here we deliver what wood is needed in that part of the camp. No one from over there is allowed out to work by the SS. The main work in the second camp still consists of digging up and incinerating the bodies from the old transports.”[3]

2.2. The Subdivision of the Camp and its Significance

Before we continue it is important to note some alleged features of the Treblinka camp structure. As per eyewitness testimony, Treblinka was divided into two main sections: the “lower camp” where the deportees were received and where their deposited clothing was sorted, and the smaller “upper camp” which supposedly contained the gas chamber buildings as well as the mass graves and the “grills” for the cremation of the corpses. The two sections were separated by a camouflaged wire fence and a huge sand rampart. In general the Jewish prisoner workers of these two camp sections were kept separated from each other.[4] Richard Glazar was part of the Jewish work commando in the lower camp and thus not a witness to the alleged extermination and incineration process per se. He therefore provides no information regarding the construction or fuel consumption of the cremation pyres.

2.3. Summary of Glazar’s Statements

Let us reiterate the essentials of Glazar’s testimony. First of all, he tells us that the task of the Jewish inmate workers was to “clear the woods around the perimeter of the camp.” Because the trees are felled around the camp’s perimeter they are “hauled into” the camp, not taken there by trucks or other vehicles. Next we are told that the trees, which are identified as pines, are sawn and split at a lumberyard in the lower camp before delivered at a nearby gate to the “second camp” (= upper camp). It is apparent that not all wood is taken to the upper camp, since Glazar writes that he and the other workers delivered “what wood [was] needed in that part of the camp.”

3. Wooded Areas at Treblinka 1936-1944

3.1. The Sources

What happens if we compare Glazar’s statement to known facts? As sources for comparison I will use a) a detailed map of the area drawn in 1936, six years previous to the construction of the camp;[5 ] b) two air photos taken of the former camp site in 1944 (May 15 and an unknown date in November respectively); c) various ground photos from the “Kurt Franz album” showing trees surrounding the camp during its period of functioning; and d) various ground photos of the camp site as it looks today.

3.2. The Perimeter of the Camp

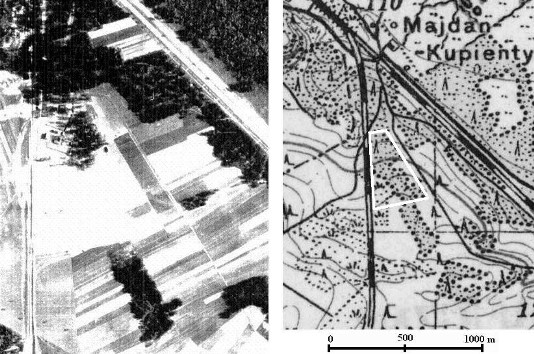

As a starting point for our comparison, we need to mark out the perimeter of the Treblinka II camp on the 1936 Polish map. This is most easily done by consulting the Luftwaffe air photo of the Malkinia-Treblinka area that was taken on May 15, 1944.[6] In this photograph the former Treblinka II camp area is clearly visible as a whitish field, except for the northern part of the camp which has not been razed and still contains five or possibly more buildings. A quick comparison of the map and the photo reveal that the small unpaved road or path which crosses the railway side spur just to the west of the northernmost part of the camp is visible in both, even if it is more apparent in the November 1944 air photo.[7] As further points of reference we have the small road or path leading straight south-south-east from an open rectangular field just to the north-east of the camp. As visible on the map, this road later bends in a more eastern direction and ends in the nearby village of Wólka Okraglik. We can also use the main railroad (visible to the upper right on the air photo) and the railway side spur (running in direction of the Treblinka I labor camp, located approximately 2 kilometers to the south of Treblinka II) to determine where on the map we should draw in the future perimeter. The result is presented below in Illustration 1.

3.3. Wooded Areas inside the Future Camp Perimeter

A quick glance at Illustration 1 reveals that a large portion of the future camp site was wooded in 1936. On the 1944 air photos we see that only the northernmost and the north-eastern part of the wooded area still remains. It is obvious that most, if not all, the other trees – corresponding to approximately 6 hectares – were felled during the construction of the camp.

Could the wood from these trees have been used for the cremations? This seems unlikely given that the order to cremate the corpses in the Aktion Reinhardt camps (Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka) allegedly was not given until autumn 1942,[8] whereas the construction of the Treblinka “death camp” was begun in May the same year.[9] The felled trees would thus not have been saved for this purpose. It is more likely that the resulting wood was used in the construction of the camp or sent away.

3.4. Evidence of Tree-felling in the Areas Surrounding the Perimeter

From looking at Illustration 1 we can draw the conclusion that, besides the trees felled at the construction of the camp, the wooded areas in the immediate vicinity, i.e. just to the north and north-east of the camp perimeter, were left intact in 1944, as their outlines on the air photos are virtually identical with those marked out on the 1936 map. But how about the forests further away from the camp?

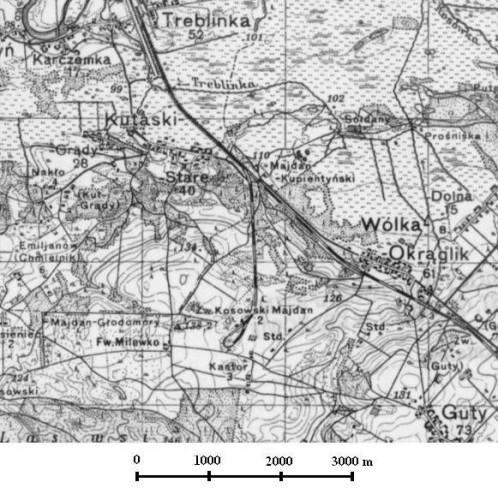

By looking at a larger section of the 1936 map (Illustration 2) we see that there are large wooded areas to the north of the future camp site. If one continues further north, the terrain turns into a mix of meadows and marshland, due to the proximity of the Bug River. South of the camp there are mainly tilled fields. The wooded areas located within a 2 km radius of Treblinka II amount in total to less than 4 square kilometers.

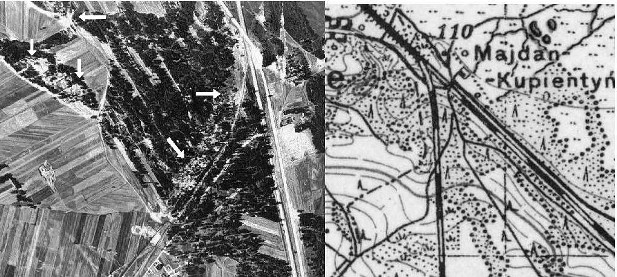

In Illustration 3 we see the portion of the November 1944 air photo showing the woods north of the liquidated Treblinka II, again compared with the 1936 map. The zones showing traces of deforestation are very limited. One may estimate their total area to 10 hectares at the very most. There is no guarantee, however, that parts of this tree-felling was not done after the liquidation of Treblinka II, i.e. in late 1943 or early 1944.

The argument that the SS might have replanted the felled forest, thus covering up the traces of deforestation, is not valid for two reasons. First, it is only alleged that the camp site itself was camouflaged with lupins and pines.[10] Second, if new trees were planted in mid-to-late 1943, they would still be no more than saplings in 1944, and thus the deforested areas would still be clearly visible as white or light grey zones on the air photos, with the recently planted trees appearing as small black dots at best.[11]

4. The Amount of Firewood Needed for Outdoor Cremations

4.1. Characteristics of the Woods near Treblinka

Ground photos taken at the former Treblinka camp site during the present era show the woods surrounding the meadow where the camp once stood to consist dominantly of fir trees and pines, with only smaller amounts hardwoods (leaf-bearing trees).[12] This is confirmed by contemporary ground photos taken by SS-Untersturmführer Kurt Franz and showing trees standing within the camp perimeter.[13]

Jewish witness Samuel Willenberg, who worked in the Tarnungskommando (camouflage commando), repeatedly describe the trees felled in the nearby woods as pine trees. In one passage he describes hauling “newly felled pines, each about 6 meters long” into the camp to be used as parts of the fence.[14]

4.2. The Difficulty of Outdoor Cremations

To cremate a human body using firewood as primary fuel is nothing easily accomplished. Criminal Inspector and Technician Lennart Kjellander of the Swedish Rikskriminalpolisen has made the following comment on incineration of human corpses outside of crematory ovens:[15]

“Large amounts of fuel, several cubic meters of wood, are necessary in order to cremate the body. […] High temperatures and access to large amounts of dry wood is a must. And it takes time. It is nothing that can be done in a few hours.”

Kjellander’s statement is confirmed by data we have on the firewood consumption of traditional Hindu funeral pyres: according to these, between 300 and 600 kg of firewood is required to cremate a single body.[16] Those funeral pyres are very primitive constructions where the dead is simply placed on top of a stack of wood. However, the slightly more advanced method of placing a grate on top of the pyre, like in the “grills” reportedly used at Treblinka, is not much more fuel efficient, as will be seen in the next paragraph.

4.3. The Amount of Firewood Required at Treblinka

According to the calculations of revisionist historian Carlo Mattogno, a dessicated corpse with an average weight[17] of 45 kg requires approximately 160 kg of seasoned wood to incinerate, since 3.5 kg of wooden fuel (plus 0.1 liter of ethyl alcohol) is needed to burn 1 kg of flesh.[18] Those figures, based on Mattogno’s own experiments with animal tissues, are confirmed by data derived from cremations of human corpses on pyres with metallic grills carried out in India.[19]

The number of Treblinka victims is usually stated as 870,000. This is the figure given by the Encyclopedia of the Holocaust[20] and which appears most commonly in reference works. To incinerate this number of bodies a total of (870,000 x 160 =) 139,200,000 kg or 139,200 tons of firewood would be required. As Mattogno further notes, a 50-year-old fir forest yields approximately 500 tons of wood per hectare,[21] which means that (139,200 ÷ 500 =) 278.4 hectares of forest or nearly 2.8 square kilometers would have to be cut down, corresponding to approximately 75% of the wooded areas north of Treblinka.

4.4. The Importance of Wood Seasoning

It is important to note that Mattogno is calculating with seasoned wood, as this is crucial for estimating the heating (calorific) value of the fuel. We should also recall Inspector Kjellander’s statement that “large amounts of dry wood” are required to incinerate a corpse.

Wood seasoning is essentially a drying process, where a large percent of the watery content of “green” (i.e. fresh) wood is reduced, usually to between 10 and 20%,[22] either by letting it air dry in a place where it is stacked with spaces in between the individual pieces of lumber and sheltered from moisture, or by drying it in a kiln. As air-drying is very slow in cold or humid weather, it usually requires that the wood is left out over a summer (hence “seasoning”). Since it is difficult to remove the moisture from whole logs, the timber is usually sawed up before it is left to dry.[23]

I must point out here that no witness and no historian has ever claimed that Treblinka II had dry kilns, and repeat the fact that there exists no evidence whatsoever, whether documentary or testimonial, for transports of firewood to the camp. If the trees felled around Treblinka were indeed seasoned, then the method used would have been air-drying. According to Glazar trees were “sawn and split” and stacked in “mounds”. But would it really have mattered much if the wood was left to dry, or if it was used more or less directly? An old agricultural article has the following to say on the use of green wood as fuel:[24]

“Wood seasoned or dried at a temperature of 100° [Fahrenheit] weighs about one-third less than green wood; for while some kinds will lose only about 25 per cent, there are others that will lose 50 per cent. As a cord of green wood will weigh on an average more than 4,000 pounds, every cord will contain some thirteen hundred pounds of water, or about one hundred and seventy gallons. This water must be raised to the boiling heat, and expelled by evaporation before the wood containing it can possibly burn. All the heat required for this purpose passes off in the latent state, and is lost to all useful purposes. The man, therefore, who burns green wood, loses precisely as much caloric, or in other words, of his wood, in every cord, as would be required to boil away 170 gallons of water. What part that would be, he can estimate for himself.

‘But,’ says the advocate of green wood, ‘all the fluids of the living tree are not water. The sap holds in solution sugar, gum, starch, resin, &c., all of which are inflammable substances, or will burn.’ This is true, but none of these substances are lost when green wood is dried; all remain for the benefit of the fuel; on the contrary, none of these will burn until free from the water holding them in solution, and much of them is driven off by the heat required for that evaporation. View the matter then as we may, there is a loss in burning green wood.”

Green wood from softwoods (conifers) – such as pine trees and fir, the predominant trees in Treblinka area – typically contain approximately 55% water by weight, which is, generally speaking, higher than the moisture content of hardwoods.[25 ]The time required for complete seasoning varies from 1 to 4 years depending upon the type and cross-sectional area of wood.[26] Air drying hardwoods generally takes 6-12 months, provided that the felled trees are sawed into boards with a thickness of 2.5 cm.[27] Given the higher moisture content of softwoods, and the fact that firewood usually is sawed into pieces much thicker than 2.5 cm, it is reasonable to assume that the wood felled at Treblinka would have taken at minimum 1 year to season.

Glazar on the other hand writes that the clearing of “the woods around the perimeter of the camp” began during the period when the final transports from the liquidated Warsaw ghetto arrived,[28] i.e. in April 1943.[29] According to Holocaust historian Yitzhak Arad, all interred corpses had been exhumed and cremated by the end of July 1943.[30] Arad concur that the cremations at Treblinka began at earnest in April,[31] so that the wood could have been air-dried for at maximum 4 months, which corresponds to a not even half-seasoned state. Since it is alleged that on average 7,000 corpses were cremated daily,[32] the felled wood would have had to be used almost immediately, so that the cremation at Treblinka of allegedly more than 800,000 corpses was “in fact” carried out using green wood as fuel. It follows that significantly more than 2.8 square kilometers of forest – perhaps 4 or even 5 – would have had to be cut down to fill the fuel requirement. The wooded areas north of the camp would therefore have been completely gone at the time the 1944 air photos were taken.

4.5. The Real Number of Cremated Bodies

Since the felling of 1 hectare of forest would produce the fuel needed to cremate (870,000 ÷ 278.4 =) 3,125 bodies, but significantly fewer if the wood was not seasoned, it follows that the air photos, rather than confirming the claims of 870,000 incinerated gas chamber victims, indicate a number of cremated bodies in the range of some ten thousands. It is likely that out of the at least 713,555 deportees sent to the camp in trains, a small percentage perished en route due to exhaustion, dehydration, illnesses, and pressure injuries or suffocation caused by panicking fellow deportees. It is claimed that an especially large number of en route deaths, caused by loaded deportation trains being delayed at way stations, took place during Dr. Irmfried Eberl’s time as camp commandant.[33] In late August 1942, Eberl was fired for incompetence and replaced by Franz Stangl.

5. Other Witnesses to Tree-felling and Cremations at Treblinka

In his book Surviving Treblinka, witness Samuel Willenberg never mentions firewood in connection with the cremations in the “upper camp.” He speaks of a “woodcutter commando” working inside the camp, splitting tree trunks with axes, and also describes himself and another prisoner having a conversation behind “a large pile of cut logs,” but no deliveries of wood to the “upper camp” are mentioned.[34] Likewise, Willenberg does not report on any transports of wood fuel to Treblinka II from the outside, despite describing in detail transports of other material to the camp.[35] The only kind of fuel mentioned by Willenberg in connection with the cremations – which he did not witness firsthand – is crude oil.[36]

It is worth noting that Glazar and Willenberg contradict each other when describing how the rails used for the “grills” (cremation grates) were procured. When interviewed by Gitta Sereny, Glazar stated that prisoners, possibly including him, were sent “into the countryside to forage for disused rails.”[37] Willenberg on the other hand writes that the rails were delivered to the camp with a train.[38]

Yankiel Wiernik, in his 1944 pamphlet A Year in Treblinka describes constructing stock houses and fences from trees apparently felled in the vicinity of the camp, but never mentions any tree-felling activity in connection with the cremations, which he claims to have witnessed first-hand. Wood is not even mentioned as a fuel by Wiernik.[39]

No tree felling in order to procure wood fuel for cremations is mentioned in Sereny’s book Into that Darkness, which contains alleged transcripts of interviews with Treblinka commandant Franz Stangl as well as statements by the Jewish witnesses Richard Glazar, Berek Rojzman, and Samuel Rajzman.

I have managed to find no testimonial evidence contradicting Glazar’s statement that the firewood used for cremations at Treblinka II was taken from wooded areas in the vicinity of the camp.

6. Summary and Conclusion

We know from documents that more than 700,000 – probably around 800,000 – Jewish deportees were sent to Treblinka II during its period of operation 1942-43. According to established historiography – which in the case is based almost exclusively on eyewitness testimony – this was a “pure extermination camp” where all Jews who arrived to the camp were killed in homicidal gas chambers within only a few hours, except for a handful of Jews selected to carry out work related to the killing process. The victims were initially buried, but starting March 1943 – or possibly on smaller scale in November 1942 – they were instead burned on cremation pyres. The buried victims were then exhumed and incinerated on the same pyres. This work was supposedly completed by the end of July 1943. The Treblinka II camp was completely dismantled in September 1943.

The witness Richard Glazar claims that the wood used to fuel the pyres was taken from “the woods around the perimeter of the camp.” Using real-life data from experiences with open-air incineration we can estimate with a high degree of certainty the amount of firewood that would be needed to incinerate the alleged number of corpses. This corresponds to approximately 3 square kilometers of forest. Realistically, however, this area would be much larger, as it follows from the chronology of Glazar’s testimony as well as established historiography that there would have been no time to season the wood. The cremation pyres would therefore have had to use “green” wood as fuel, which is less efficient than seasoned wood due to its higher moisture content.

By comparing a detailed 1936 map of the Treblinka area with air photos taken by the Luftwaffe in May and November 1944 we are able to estimate the scope of contemporary deforestation in the area. If 870,000 bodies had really been burned at Treblinka, then the procurement of the required fuel would have denuded the entire wooded area north of the camp site. The air photos show that this is clearly not the case. Rather, the visible possibly deforested areas – amounting to less than 10 hectares – indicate the cremation of at most some ten thousands of bodies.

The argument that perhaps the witnesses are wrong, and only a fraction of the corpses were burned, does not hold up, since the Soviet and Polish forensic examinations carried out in the period 1944-1945 would then have discovered hundreds of thousands of unincinerated corpses at the former camp site and subsequently announced their findings to the world as the ultimate proof of “German-Fascist” barbarism. Needless to say, they didn’t.[40] There only remains the conclusion that a small percentage of the Jewish deportees died en route to the camp and that the remainder where sent somewhere else, most of them likely to occupied USSR territory. The witness Richard Glazar has thus inadvertently helped confirm the revisionist hypothesis that Treblinka II was a transit camp.

Notes

| [1] | Cf. Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, Indiana University Press, Bloomington/Indianapolis 1987, p. 42, 81, 173-177. The so-called Höfle telegram discovered in 2000 reveals that 713,555 Jews had been deported to Treblinka up until December 31, 1942. |

| [2] | Richard Glazar, Die Falle mit dem grünen Zaun. Überleben in Treblinka, Fischer Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2002. |

| [3] | Richard Glazar, Trap with a green fence, Northwestern University Press, Evanston 2005, p. 115. |

| [4] | Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, op. cit., p. 41, 112. |

| [5] | The map is entitled “Mapa Taktyczna Polski 1:100 000” and was issued by the Polish Wojskowy Instytut Geograficzny. This map is viewable online as a large image file: http://www.mapywig.org/m/wig100k/P38_S34_MALKINIA.jpg. More information on this map (in Polish) can be found at: http://igrek.amzp.pl/details.php?id=4263 and at www.mapywig.org |

| [6] | United States National Archives, Ref. No. GX 120 F 932 SK, exp. 125. |

| [7] | United States National Archives, Ref. No. GX 12225 SG, exp. 259. |

| [8] | Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, op. cit., p. 171. |

| [9] | Ibid., p. 37. |

| [10] | Ibid., p. 373. |

| [11] | The possible counterargument that the SS could have planted already grown trees does not hold up either, as this would have required a simply ridiculous amount of transportation and plantation work. |

| [12] | C. Mattogno, J. Graf, Treblinka. Extermination Camp or Transit Camp?, op.cit. pp. 339-340, 342. |

| [13] | Some of them are viewable online at http://www.deathcamps.org/treblinka/photos.html |

| [14] | Samuel Willenberg, Surviving Treblinka, Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1989, p. 110. |

| [15] | “Svårt bränna upp lik”, Aftonbladet, Stockholm, February 16, 2006. |

| [16] | Arnulf Neumaier, “The Treblinka Holocaust”, in Germar Rudolf (ed.), Dissecting the Holocaust. The Growing Critique of ‘Truth’ and ‘Memory’, 2nd edition, Theses & Dissertations Press, Chicago 2003, p. 495. The Indian Teri company gives the fuel consumption of a cremation of one body using the “traditional system” as 400-600 kg; Carlo Mattogno, “Bełżec or the Holocaust Controversy of Roberto Muehlenkamp”, online: https://codoh.com/library/document/belzec-or-the-holocaust-controversy-of-roberto/ |

| [17] | This average weight is based on the assumption that one third of the alleged victims were children, and that the average weight was reduced from 58 to 45 kg through dessication caused by the decomposition process. |

| [18] | C. Mattogno, “Combustion Experiments with Flesh and Animal Fat”, The Revisionist Vol. 2 No. 1 (February 2004), pp. 68-70; C. Mattogno, J. Graf, Treblinka. Extermination Camp or Transit Camp?, op. cit., p. 149. |

| [19] | Calculated from data provided by the Teri company on cremations utilizing an “improved open fire system using a metal grate”; C. Mattogno, “Bełżec or the Holocaust Controversy of Roberto Muehlenkamp”, op. cit. |

| [20] | Israel Gutman (ed.), Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, MacMillan, New York 1990, vol. 4, p. 1486. |

| [21] | More precisely 496. |

| [22] | Cf. D. Mukherjee, Fundamentals of Renewable Energy Systems, New Age International, New Delhi 2004, p. 65. |

| [23] | Rex Miller, Audel Carpenter’s and Builder’s Math, Plans, and Specifications, 7th edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York 2004, pp. 44-47. |

| [24] | “Dry or green wood for fuel”, The Cultivator (published by the New York State Agricultural Society), Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 1844), p. 21. |

| [25] | F. William Payne, Advanced technologies: improving industrial efficiency, Fairmont Press, Lilburn (GA) 1985, p. 46 |

| [26] | H.S. Bawa, Workshop Practice, Tata McGraw-Hill, New Delhi 2003, p. 106. |

| [27] | Ben Law, The woodland way: a permaculture approach to sustainable woodland management, Permanent Publications, East Meon 2001, p. 101. |

| [28] | Richard Glazar, Trap with a green fence, op. cit., pp. 114-115. |

| [29] | Y. Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. The Operation Reinhard Death Camps, op. cit., p. 127. |

| [30] | Ibid., p. 177. |

| [31] | ”In this camp the entire cremation operation lasted about four months, from April to the end of July 1943”; Ibid. |

| [32] | Ibid., p. 178. |

| [33] | Ibid., pp. 84-88. |

| [34] | S. Willenberg, Surviving Treblinka, op. cit., p. 140. |

| [35] | Ibid., p. 107, 137. |

| [36] | Ibid., p. 107. |

| [37] | Gitta Sereny, Into that Darkness. An Examination of Conscience, Vintage Books, New York 1983, p. 220. |

| [38] | S. Willenberg, Surviving Treblinka, op. cit., pp. 107-108. |

| [39] | Yankel Wiernik, A Year in Treblinka, American Representation of the General Workers’ Union of Poland, New York 1944. |

| [40] | C. Mattogno, J. Graf, Treblinka. Extermination Camp or Transit Camp?, op. cit., pp. 77-90. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, Vol. 1, No. 2

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: