Viktor Emil Frankl in Auschwitz

In 2001, the Journal of Historical Review published a short article penned by Theodore O’Keefe about the famous Austrian psychologist Viktor Frankl.[1] On the basis of statements by Frankl and of research by orthodox historians, O’Keefe showed that Frankl was not particularly truthful in his recollections about his stay at the Auschwitz Camp. In response to a German translation of OKeefe’s paper, Austrian engineer Walter Lüftl wrote a letter to the editor, in which he excused Frankl’s inaccuracies, and emphasized his love of truth otherwise. The present article systematically examines Frankl’s account of his experiences at Auschwitz. The reader is left to judge, how far Frankl’s love of truth really does, when it comes to his experiences at and around Auschwitz.

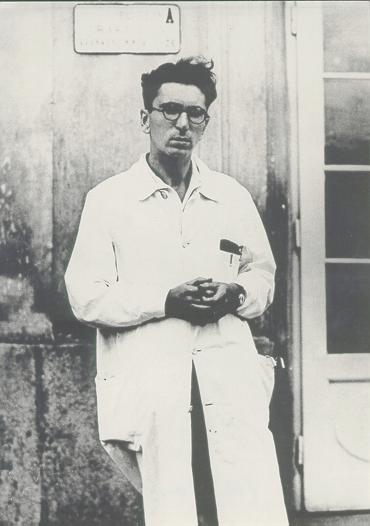

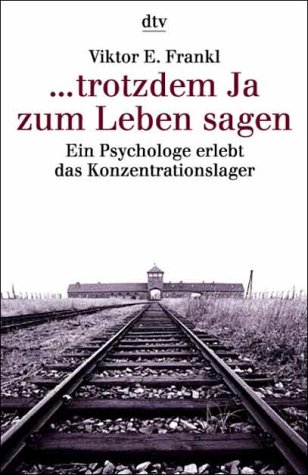

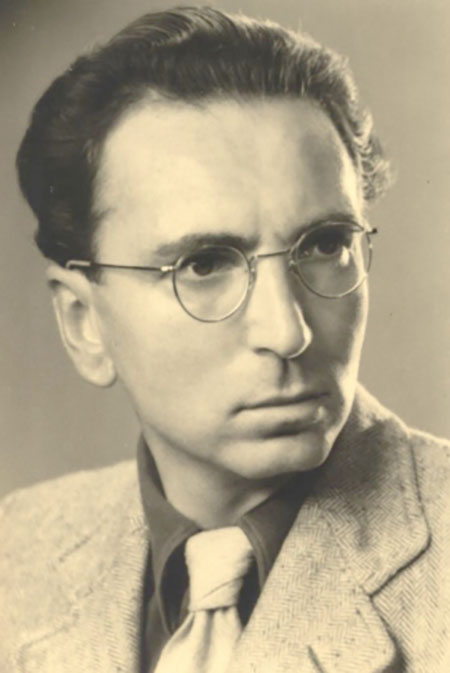

The well-known psychiatrist and psychotherapist Viktor Emil Frankl, who died in 1997, was interned in the Auschwitz Concentration Camp because of his Jewish origins. He wrote an account of this time, which was first published in German in Munich in 1977, and was last reprinted in 1998. Its original title translates to Saying Yes to Life Anyway: A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp (…trotzdem Ja zum Leben sagen: Ein Psychologe erlebt das Konzentrationslager). However, the English translation’s title is totally different: Man’s Search for Meaning: An Introduction to Logotherapy. This book was a bestseller, especially in the USA, where two million copies were sold.

The blurb for the German edition by the Kösel publishing house (here quoted after the second German edition, Munich 1978) praises the book as a “documentary didactic piece” and “masterpiece of psychological observation.” In the following, the text will be examined by a linguist and historian for the coherence of its presentation. It should be possible, in the spirit of our inalienable civil rights and within the framework of a scientific debate, to approach a short section of recent German history without prejudice, and to draw unambiguous conclusions.

Right at the beginning (p. 15), Frankl emphasizes that his writing is more of an “account of experience” rather than a “factual report.” Apart from the obvious ambiguity of these terms, we must assume that the psychologist has experienced what he reports, meaning that he wants to convey facts. He then goes on to say that his descriptions “are less concerned with events in the famous, large camps than with those in the notorious satellite camps.” This statement must be met with caution, because it is its obviously illogical, for in his book, Frankl reports only on Auschwitz, which is recognized by all literature as the largest camp of all.[2]Right at the beginning Frankl emphasizes (p.15) that his writing is an “account of experience”, less a “factual report”. Apart from the obvious ambiguity of this definition, we must assume that the psychologist has experienced what he reports, that is, that he wants to give facts. He then goes on to say that his descriptions “are less concerned with events in the famous, large camps than with those in the notorious branch camps”. This statement must be met with caution because of its obvious illogicality, for in his book Frankl reports only on Auschwitz, which is recognized by all literature as the largest camp of all. Hence, already on this first page of his report, Frankl becomes entangled in contradictions that are difficult to resolve.

On p. 17, Frankl reports on the separation of prisoners into those fit for work and those unfit for work, the reader cannot get a clear picture, because the account begins with the remark “Let us assume….” The reporter then continues: “because one suspects, and not wrongly, that they go into the gas.” A scientist, however, would not be satisfied with assumptions, because an experience report was announced. What he saw, Frankl does not write. On p. 21, he reaffirms: “Here, however, facts are to be brought forward only insofar as the experience of a person is in each case the experience of actual events.” Linguistics calls such formulations a tautology. Frankl then goes on to say that, for the inmates, “what they themselves have actually experienced, should be attempted to be explained here with the scientific methods available at the time.” Again, it remains unclear to the reader what is to be explained here by “scientific methods.” What the detainees experienced does not require any scientific explanation.

In the second chapter, titled “The First Phase: Admission to the Camp,” the author describes the “shrill whistle of the locomotive, resounding like a foreboding cry for help from the mass of people personified by the machine, led by it into a great disaster” (p. 25). A procedure becomes apparent here that Frankl maintains throughout his account. He interprets a factually established and actually occurred fact, the whistle of the locomotive, in such a way that a thought association with the shrill cry for help of tormented masses arises in the reader. Obviously, this arbitrary montage of different, unrelated things is supposed to arouse fear and pity in the reader. This has nothing to do with the “scientific methods” announced shortly before. At the bottom of the same page, the author announces another detail: some of his fellow prisoners have premonitions and “horror visions.” The reporter himself “believed to see a few gallows, and people hanging from them.” Did he only believe to have seen it, or did he actually see it? The reader may be permitted to ask this. Shortly thereafter (top of p. 26), Frankl hears orders getting shouted in a harsh voice that “sounds like the last cry of a murdered man.” Here we see again the method analyzed earlier of contracting and fusing things experienced with those only imagined. The exhortation of grief and consternation has, as can be seen, reached an innumerable crowd of readers.

Among the most horrific experiences Frankl had to go through right at the beginning of his stay at Auschwitz is the following. He asks a fellow prisoner where his friend P. is, and he learns:

“A hand points to a chimney a few hundred meters away, from which a jet flame many meters high flares up eerily into the vast Polish sky, there to dissolve into a gloomy cloud of smoke.”

Every researcher of contemporary history has been familiar for decades with this jet flame, reported by countless witnesses, as a topos, as it is called in literary studies. Recent revisionist research, however, has raised considerable doubts on this point. During the cremation of one or even several corpses in crematoria furnaces fired with coke – which all German wartime crematoria were – no jet of flames ejecting out of the chimney can be produced. First, the usually emaciated bodies of deceased concentration camp inmates had hardly any body fat that could have produced any flames. Next, coke does not produce any considerable flame at all. And finally, the smoke ducts of all Auschwitz crematoria were some 30 meters long. Hence, any flame ever getting produced burned out long before these gases reach the end of the chimney.[3] The author asked the director of a crematorium of a large German city about this matter, and received the answer that it was impossible that during the incineration of one or more corpses, jets of flames or even “many meters high” flames could develop. At this point, therefore, a question mark must be put over Frankl’s report.

Newly arrived inmates had their hair shorn – as usual – and then they had to go under a shower. The passage reads:

“pleased and highly delighted, individuals find that from the shower funnels really – water drips down […]” (p. 33)

Although it remains unclear why only “individuals” notice that water came out of the showers, and it remains equally unclear why it only “drips down”, but at least this experience seems to have actually taken place in this or a similar form, because on p. 35, Frankl confirms it as follows:

“Because, again: water really comes out of the shower funnels!”

Two remarkable passages, as every afficionado realizes, because for four decades we have been told that these showers were only camouflage for something else. Should we now trust a scientist of supposed international standing like Viktor Emil Frankl less than controversial reporters like Ada Bimko, Imre Kertész, Jerzy Tabeau, Alfred Wetzler and many others? This question is all the more pressing, since Frankl announced that he wanted to apply “scientific methods.”

Frankl repeatedly gives detailed accounts of life in the camp, but me mixes true events with improbable claims. The beds in which the prisoners lay are described as three-story high (p. 36), which agrees with the reports of other inmates.[4] However, Frankl also reports that he had to “put his head on the arm that was almost twisted upwards.” This passage remains unclear to any unprejudiced reader. There are several reports on “typhus barracks” and those who have fallen ill with typus, of “outpatient centers”, and of “resting times” for particularly ill prisoners.[5] These statements should be given special attention, since they are clearly in jarring contradiction with the other events claimed for the alleged Auschwitz death camp, but on the other hand, they are in accordance with witness testimonies, showing that a great deal was done in the camp for the medical care of the inmates.[6]

If the remarks of the professor of psychology on medical care at the Auschwitz Camp have a weight worthy of attention simply because of their frequency, other observations repeatedly stand out which must be taken with greater caution. One day, for example, while holding a hot bowl of soup:

“I happened to squint out at the window: outside, the corpse that had just been taken out was gawking in through the window with staring eyes. […] this experience would not have remained in my memory: the whole thing was so lacking in emotion” (p. 44).

How are we to imagine this happening? Did Frankl deceive his memory here? What does he mean by “lacking in emotion”? Immensely characteristic of Frankl is the account of a drive through Vienna at night (pp. 58-60). Although German cities were darkened because of the danger of air raids, shortly after midnight, the author sees the alley “in one of whose houses where I came into the world.” Although Frankl was in a “small prison van,” which also had only “two small barred hatches,” and he only looked out “standing on his tiptoes,” he claims to have seen everything clearly. He then continues:

“We all felt more dead than alive. It was assumed that the transport was going to Mauthausen. We therefore did not expect to live longer than an average of one to two weeks. I saw the streets, squares, houses of my childhood and home – this was a clear feeling – as if I had already died, and was looking down on this ghostly city like a dead man from the afterlife, a ghost himself.”

Only after Frankl claims to have had this experience, does he become specific. He asks his fellow prisoners to “let me come forward just for a moment,” so he ca look outside. But his request is denied (p. 60 top). This whole scene, one of the highlights of the account of his experience, is questionable. Because of the blackout, which in all likelihood would have affected Vienna as well, Frankl would not have been able to see much anyway. As far as we know, a small van for prisoners is not mentioned in any other source. It also seems doubtful whether Frankl could have seen the alley of his childhood at all, because he mentions only after the description that he had tried to get someone to let him look through the “small barred hatch”, but this was denied.

Apparently, he was not in Mauthausen at all, because he writes nothing about it. The life expectancy of a few weeks (a topos that is found in similar form at least a dozen times in the text, and was repeatedly claimed by others) was then unmasked as mere conjecture by his actual lifetime of another forty years.

The accumulation of ideas like “ghost”, “death” etc. at this revealing place allows the assumption that, with some self-pity, he tries to make an impression on a sensation-ready readership. That can be imputed. The author of this article, who has met many psychologists in the course of time, has never met one who would have been able to use the probe of psychology on himself.

To the sensation-seeking reader’s disappointment, a chapter titled “Sexuality” (pp. 57f.) does not contain any carnal scene that other accounts are teeming with. These erotica in the face of the gas chambers have already been subjected to critical analysis several times, and partly relegated to the realm of kitsch. Recently, the Jewish dissent Norman Finkelstein has denounced such erotica in the face of mass death as “holoporn,” not without cynicism.[7] Nothing of this kind can be found in Viktor Emil Frankl’s account. Staying faithful to his wife makes his report sympathetic. He calls her the “beloved being” despite all distress. I would like to raise doubts, however, when he says “that the sexual instinct is generally silent.” He does not seem to be aware of the brothel that existed inside the Auschwitz Camp. Frankl entangles himself in a contradiction here when claiming that “even in the dreams of the prisoners, sexual contents almost never appear.” But three lines further he writes that “the prisoner’s whole longing for love and other impulses [sic!] certainly appear in dreams.” From the point of view of psychology and statistics, it would have been interesting to know, how many fellow sufferers he actually interviewed on this issue. Or should it have been only a veiled self-projection here?

There is no end of improbabilities. Frankl shares the most remarkable one on p. 94. He succeeded in escaping from hell. However, he returns voluntarily for unconvincing reasons, and provides himself “with a few rotten potatoes as provisions” (p. 95). There is no need to comment on this. After endless, patiently endured suffering, Viktor Emil Frankl reports that he was released from the Auschwitz Camp in early 1945. The release is said to have taken place after the Auschwitz Camp was captured by the Soviets on 27 January 1945.[8] It is just too bad that other scientists have meanwhile established, on the basis of preserved documents, that Frankl had left Auschwitz for Bavaria already in late October 1944, where he remained interned in the Kaufering Camp III, which Frankl himself confirmed in an interview.[9]

Accordingly, it is not surprising that Frankl’s account of his liberation cannot be true:

“There one comes to a meadow. There one sees blooming flowers on it.” (p. 141)

Two pages later, he affirms:

“Then one day, a few days after liberation […] you walk through flowering meadows […] larks rise […] and then you sink to your knees.” etc. etc.

I refrain from commenting this, but I would like to point out that in Auschwitz, located west of Krakow, there may have been snow at that time. Ornithologists may decide whether larks rise in January.[10] Thus, his report itself indicates that he was not liberated in January from the Auschwitz Camp, as claimed, but in the spring in Bavaria by the Americans.

Some of the reports of the professor of psychiatry, who – we remember – wanted to apply scientific methods, coincide with the findings of contemporary historical research. I pick out two. Right at the beginning of his remarks (p. 26), Frankl reports that he had heard prisoners speaking “in all kinds of European languages.” Indeed, in Auschwitz, as in other camps, people from at least a dozen nations were imprisoned, among them Gypsies, but also Germans, among these criminal as well as innocent individuals, homosexuals, Freemasons, Catholics, resistance fighters, Social Democrats, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Communists, etc. The death books of the Auschwitz Camp published in 1995, contain about 65,000 names, among them about 40% Jews.[11] This publication confirms that historical facts are dealt with by the orthodox in a very one-sided and falsifying way, since in an inadmissible way and contrary to any scientifically exact presentation, only the sufferings of one nation are remembered, but not those of all other nations.

On pp. 76/79, Frankl mentions an “air raid alarm.” Air raids on Auschwitz have been known for a long time,[12] but are denied by influential persons, among them the Munich professor Wolffsohn.[13]

The Pilpul

Let us draw the conclusion: Viktor Emil Frankl’s omissions do not stand up to examination on the basis of source exegesis, textual criticism and historical facts. The scientific value of the treatise must therefore be estimated as low. The author exposes himself to the suspicion of being the object of autosuggestions in many instances, which in turn would have to be the subject of a psychological analysis, although or because the author himself was a psychologist. The assumption should be made here that Viktor Emil Frankl, when writing his report, was committed to the imaginary figure Pilpul, which could have been effective in his subconscious, as we call this since Sigmund Freud. This Pilpul is a constituent of Jewish thinking, and reminds to its oriental origin. As far as I can see, philosopher Hans Dietrich Sander was the first to refer to the Pilpul in the present context.[14]

A wide space opens up here for historians of for philosophy. The Pilpul corresponds roughly to what Sophism (e.g. Protagoras) described as “making the weaker argument the stronger one.” Aristotle described something similar in his Rhetoric (Book 3, Ch. 7), where he stated that, if one “expresses the soft harshly and the hard gently, the thing loses its credibility.” This is a dialectical figure that turns logic into arbitrariness, in our case mixing experiences with imaginations indiscriminately, and passing off this semblance of truth for the whole truth. The most extreme form of the Pilpul might be the work of Daniel Goldhagen, which was subjected to a sharp criticism by Norman Finkelstein (as before), and which communicates nothing less than that the Germans had “killer genes.” Excesses of the most absurd kind, which remind us with their hypertrophic phantastic nature of One Thousand and One Nights. This book was also a commercial success. Norman G. Finkelstein’s book The Holocaust Industry already alludes in its title to the possible business intentions of such products, and therefore caused unrest among those concerned, when the English edition appeared in June 2000.

Among the grotesque distortions of Pilpul are the atrocity tales of children’s hands chopped off by German soldiers in Belgium, lampshades made of Jews’ skin, and soap made of Jews’ fat, things that are no longer believed today,[15] however, were part of standard knowledge until a few years ago.

A telling light is shed on these matters by the autobiography of the former prime minister of Israel, Golda Meierson, alias Meir,[16] which, as far as I can see, has not been assessed by historians either. Mrs. Meir reported about the above-mentioned German atrocities:

“The strange and terrible thing was that none of us doubted the information we had received.”(!) (p. 165)

The next day, she had a conversation with “a sympathetic British official.” After she told him about the Nazi atrocities, the latter said:

“But Mrs. Meyerson, you don’t really believe that, do you?”

Then he told her about the “World War I atrocity propaganda and how utterly absurd it had been. I could not explain to him for what reason I knew that this was something different.” (Emphasis added.)

To which the sympathetic Brit with the “kind blue eyes” replied:

“You must not believe everything you hear.”

Mrs. Meir, however, believed.

The Frankl Report and Contemporary History Research

The research on the Third Reich carried on today in Germany and worldwide is represented by two groups, the orthodoxy, whose members teach at universities and appear in public, and the skeptics, the so-called “revisionists,” who, as the name suggests, subject certain events to a “review,” but who challenge the preordained view of history, and are therefore suppressed in many Western countries by penal law, and whose publications are banned in many countries. In Germany, for instance, hundreds of book titles and countless magazine issues are prohibited. This approach of the state corresponds to what the sociologist Ernst Topitsch characterized in his theory of science as an “immunization strategy,” meaning a school of thought must be secured by force against criticism, lest it may get threatened by competing schools of thought.[17] Similar thought patterns were analyzed by the philosopher Eric Voegelin in his sharp critique of the Marxist worldview, which he exposed as a “prohibition to ask questions.”[18]

In spite of massive prohibitions on asking questions about the events of the Third Reich, especially in the camps, one has had the astonishing experience in recent years that the two lines of research now seem to be converging. Among tenured orthodox German historians, Hans Mommsen and Ernst Nolte have boldly spoken out. The former when he denied the existence of an extermination order[19] – which, however, was nothing new to experts – and Nolte when he announced:[20]

“I cannot exclude the possibility that most of the victims did not die in gas chambers, but that the number of those who perished through epidemics or through mistreatment and mass shootings is comparatively larger.”

Nolte does not use the term “partisan shootings” here, which military historians would have used. After all, both gentlemen violated state-imposed thought verbote. Only their professorial title protected them from house searches, fines, imprisonment or worse. Ernst Nolte, however, was banned from writing in Germany’s most prestigious daily newspaper (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) and was beaten up by left-wing terrorists in a Berlin church shortly after given an extended interview to Germany’s news magazine Der Spiegel. The media were not enraged by this. It was Ernst Nolte, who in one of his last books dealt at least to some extent with the research results of the so-called revisionists in a chapter of his own,[21] something which his tenured university colleagues studiously avoid, because they all are subscribed to the immunization strategy.

A breach in the wall of silence was made by the Berlin-based Jewess Sonja Margolina, when she at least admitted the mass murders of Ukrainians – often carried out by Russian Jews – because of which she claims to have “trembled.” Unfortunately, she does not mention any numbers, and the name of an abomination like Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich appears only coyly in passing, and with an incomplete first name.[22] She even accuses her religious comrades of “suppression” of their own guilt, and thus approaches Finkelstein’s remarks. Both authors are immune from persecution by the German judiciary, because of their Jewish background.

The works of Josef Ginsburg, alias Josef G. Burg, and Roger G. Domergue Polacco de Menasce were already confiscated in the 1960s, and are still banned today and are currently not available.[23] Burg was beaten up in Munich’s North Cemetery shortly before his death. The author knows nothing about Polacco de Menasce, who accused his people of unscrupulously doing business with pornography.

It is not possible here to give an outline of the entire contemporary historical literature, orthodox and heterodox, on this controversial subject. The only intention was to provide further building blocks to the diverse and intricate mosaic of research into the National-Socialist dictatorship. Science means, among other things, to separate the false from the correct, and to describe the correct as accurately as possible. The Germans, who for decades have been reproached for their misdeeds and those of their predecessors, from which the nation literally threatens to perish mentally and thus physically, have the right to approach their own history without prejudice.

Notes

Image source: new book titles: amazon.com or amazon.de; rest: http://logotherapy.univie.ac.at/gallery/gallery.html

| [1] | Theodore O’Keefe “Was Holocaust Survivor Viktor Frankl Gassed at Auschwitz?,” Journal of Historical Review, Vol. 20, No. 5+6, 2001, pp. 10f. |

| [2] | Cf. ibid. Frankl was taken from the Theresienstadt ghetto to Auschwitz and from there, after a short time, was transferred to the Kaufering III camp in Bavaria. Editor’s note. |

| [3] | Cf. Carlo Mattogno, “Flames and Smoke from the Chimneys of Crematoria,” The Revisionist, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2004, pp. 73-78. After questioning by Dipl.-Ing. Walter Lüftl, Frankl admitted that he was possibly subject to a deception, cf. Lüftl’s letter to the editor in Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2002, p. 364. |

| [4] | Cf. the photograph in W. Stäglich, Der Auschwitz-Mythos, Grabert, Tübingen 1979, image section, editor’s note. |

| [5] | Pp. 42f., 55, 81 (“seventy comrades resting”), 82, 85, 86 (“medicines freshly arrived in the camp”), 91 (“they needed some doctors”), 93, 95, 97, 122, 132. |

| [6] | On this, see C. Mattogno, Healthcare in Auschwitz: Medical Care and Special Treatment of Registered Inmates, Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2016. |

| [7] | Cf. Ruth Bettina Birn, Norman G. Finkelstein, Eine Nation auf dem Prüfstand, Die Goldhagen‑These und die historische Wahrheit, Hildesheim 1998, p. 123: English: A Nation on Trial: The Goldhagen Thesis and Historical Truth, Metropolitan, New York, 1998. |

| [8] | Cf. Joachim Hoffmann, Stalins Vernichtungskrieg, München 1996, p. 303; English: Stalin’s War of Extermination 1941-1945, Theses & Dissertations Press, Capshaw, AL, 2001. |

| [9] | Cf. T. O’Keefe’s paper, Note 1. The date given therein for the issue of the U.S. magazine Possibilities in which Frankl’s interview appeared is incorrect. It should read March/April 1991 (not the impossible 1944; this was corrected in the online version). |

| [10] | Meyers Großes Konversationslexikon, sixth edition, Vol. 12, Leipzig/Vienna 1906, p. 434 notes under “Lark”: “In winter, it dwells in southern Europe and North Africa; some winter with us.” |

| [11] | Cf. Staatliches Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau (ed.), Sterbebücher von Auschwitz, Fragmente, K.G. Saur, Munich 1995, p. 248. |

| [12] | Cf. Udo Walendy, Auschwitz im IG‑Farben Prozeß, Verlag für Volkstum und Zeitgeschichtsforschung, Vlotho/Weser 1981, photo appendix; J. C. Ball, Air Photo Evidence, Ball Resource Service Ltd., Delta, B.C., Canada 1992; now as G. Rudolf (ed.), Air-Photo Evidence, 6th ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2020. |

| [13] | Cf. Wolffsohn in: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 24 January 1995, p. 8. |

| [14] | H.D. Sander, Die Auflösung aller Dinge, Zur geschichtlichen Lage des Judentums in den Metamorphosen der Moderne, Munich, undated, pp. 68f., 79f. |

| [15] | Cf. G. Rudolf, Lectures on the Holocaust, 4th ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Bargoed, Wales, UK, 2023, pp. 90-99. |

| [16] | Golda Meir, Mein Leben, Ullstein, Frankfurt/Main, 1983; English: My Life, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London, 1975. |

| [17] | Ernst Topitsch, Gottwerdung und Revolution, Beiträge zur Weltanschauungsanalyse und Ideologiekritik, Pullach near Munich, 1973, pp. 35, 57, 130. |

| [18] | Eric Voegelin, Wissenschaft, Politik und Gnosis, Munich 1959, p. 33 and passim. |

| [19] | In: Die Woche, 15 November 1996, together with the Viennese Hitler researcher Brigitte Hamacher. |

| [20] | Der Spiegel, No. 40, 1994, p. 85. |

| [21] | Ernst Nolte, Streitpunkte, Heutige und künftige Kontroversen um den Nationalsozialismus, Propyläen, Berlin, 1993, pp. 304f. |

| [22] | Sonja Margolina, Das Ende der Lügen, Rußland und die Juden im 20. Jahrhundert, Siedler, Berlin, 1992, pp. 84,151 |

| [23] | Many of Josef G. Burg’s writings can be found online at vho.org; editor’s note. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2023, Vol. 15, No. 3. First published in German in Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2002, pp. 304-309

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a