Intellectual Freedom and the Holocaust Controversy

In 1999, I partnered with Bradley Smith to launch a new revisionist journal, entitled The Revisionist. The Revisionist went through several incarnations through the years. Ultimately, it became the prototype for Inconvenient History, which was launched ten years later in 2009. This short opinion piece ran in that first issue of The Revisionist. Here, Bradley Smith argued for the subject that was his focus for the second half of his life – intellectual freedom with regard to the Holocaust. Bradley Smith passed away on 18 February 2016. This article is reprinted his memory. A slightly different version of this article also ran in the 6 June 94 issue of The Statesman at State University of New York at Stony Brook— Ed.

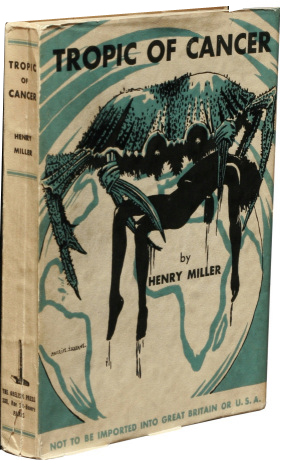

All my life I watched Jews lead the struggle to maintain a free press and intellectual freedom in America. In the 1960s, when I was a book dealer on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles, I was arrested, jailed, tried and convicted for selling a book then banned by the U.S. Government—Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. Jews from every walk of life supported my stand against Government censorship.

A.L. Wiren, then head of the Los Angeles chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, offered his offices for my defense at no cost. After my conviction, when the case went to appeal, Stanley Fleishman offered his services to me pro bono! Fleishman didn’t take my case because he admired me personally, or because he considered Henry Miller to be the greatest writer who ever lived. He took it because he was committed heart and soul—and mind—to the ideals of intellectual freedom and the spirit of the First Amendment. Today, Miller’s Tropic is shelved in every library of note in America.

Shockingly, in the 1990s, some mainline Jewish organizations have reversed direction and committed themselves to undermining intellectual freedom with respect to a single historical controversy—whether the Germans did or did not employ homicidal gassing chambers to kill millions of European Jews in a state-sponsored program of genocide. In practice, what this often adds up to, particularly on college campuses, is the perception of an organized Jewish onslaught against intellectual freedom.

On every campus where Hillel and other Jewish organizations have a presence, they lead the attack against free inquiry and open debate on the gas-chamber controversy. I am astounded that Jewish intellectuals and scholars stand idly by while the reputation of Jews as free thinkers is diminished and burlesqued by a handful of mainline Jewish extremists and censors.

Student journalists who are Jewish are under special pressure from the Holocaust Lobby to betray, not only their ideals as journalists, but the long tradition of intellectual liberty for which Jews have worked throughout the Western world. On campus, Jewish editors are attacked by well-meaning but unsophisticated Jewish students who are egged on by Hillel rabbis functioning as semi-professional censors.

Student editors who are not Jewish, while they experience all the above, must face the additional burden of being slandered as “anti-Semites” and “haters.” I understand why many are unwilling or even afraid to shoulder the burden that the ideal of a free press places on journalists with regard to the gas-chamber controversy. Yet without a free press there are no universities worthy of the name, no government that is not tyrannical, and no society that is not a burden on the lives of its citizens.

The issue here is not ethnicity or religious identity. The issue is intellectual freedom. Weighing evidence is not a hate crime, no matter what Hillel or the ADL says about it. Critiquing a government-sponsored “Holocaust” museum is not a thought crime! And charging that it is hateful to doubt what others sincerely believe is juvenile, particularly on a university campus. What are the real motives of those who would try to convince us otherwise?

The university was created as a place to exchange thought—freely. Students should not be required to ask permission from special interest groups, no matter what their ethnicity, to think for themselves. Even about the “Holocaust.” Whatever else the Holocaust was, it was an historical event. That event, as well as the controversy surrounding it, should be investigated using routine historical methods.

Thirty-odd years have passed since I was a bookseller on Hollywood Boulevard, but my conviction about the importance of intellectual freedom remains today what it was then. In the 1960s I went to court to uphold the right of students to read radical literary works. I am no less convinced today that students have the right to read every research paper that interests them, on any historical controversy whatever, including every single word ever written about the gas-chamber controversy!

Why should they not?

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 8(2) 2016

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a