Made-for-TV Movie More Fair than the “War Crimes” Trial It Depicts

Movie Review

““Nuremberg”” (television drama miniseries). Based on the book Nuremberg: Infamy on Trial, by Joseph E. Persico. Screenplay by David Rintels. Produced by Alec Baldwin, Jon Cornick, Gerry Abrams, Suzanne Girard, and Peter Sussman. Directed by Yves Simoneau. Turner Network Television (TNT). Actual running time: 180 minutes (four hours with commercials, in two parts). First segment premiere Sunday, July 16; conclusion premiere Monday, July 17. Web site: http://www.tnt.turner.com/movies/tntoriginals/nuremberg/frame_main_exclude.html

Critics of the International Military Tribunal, and its trial of Third Reich leaders held in Nuremberg after the Second World War, believe it was illegitimate because of its application of ex post facto laws, use of questionable evidence and false testimonies, mistreatment of defendants and witnesses, and hindrances to defense attorneys. (See Mark Weber. “The Nuremberg Trials and the Holocaust,” Journal of Historical Review, Summer 1992), Despite these serious failings, the judgments rendered at the IMT, and at numerous follow-up German war crimes trials, largely shape the modern view of the war. The IMT has achieved such currency that most accounts of its proceedings and verdicts blindly perpetuate the unfairness of the trial itself, with little fear that repeatedly pointing out its flaws will invalidate or even tarnish this progressive standard.

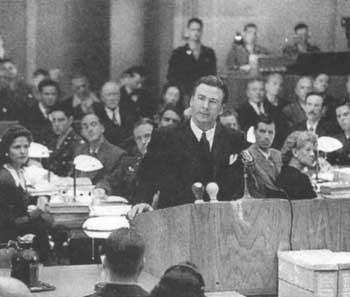

Alec Baldwin played Robert Jackson, chief US prosecutor at the Nuremberg Tribunal, in the TNT made-for-television miniseries “Nuremberg.” At the left is Jill Hennessy, who played Jackson's secretary, Elsie Douglas.

It must be remembered that even documentaries produced by Hollywood are often so far removed from the truth as to be highly misleading, and TNT’s made-for-television production of “Nuremberg” is not a documentary, but a drama. As such, it takes considerable license with the facts. Because there is little pretense here that history is being presented as it actually happened, it would be a waste of time to closely compare “Nuremberg” to the historical record.

More important is what is shown in addition to the seemingly obligatory Nazi-bashing common in films dealing with this era. For example, any mention of Adolf Hitler, Nazis or Nazism without harping on the Holocaust is inconceivable, and “Nuremberg” does its share of perpetuating the myth that the trials were necessary, fair, and unremarkable in terms of jurisprudence, largely because of what is alleged to have happened in the German-run concentration camps. But where most sympathetic treatments of the IMT differ only in their attempts to excuse its extra-legal aspects, TNT’s “Nuremberg” naively acknowledges its unfairness, as if to say that the ends (the condemnation of Nazism and the punishment of Nazi leaders) justify the means.

What’s more, some of the accused, notably Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring (Brian Cox), are convincingly portrayed as men with some depth of character, a complete departure from the typical “Nazi = evil incarnate” formula found in most British and American films made since 1933. Although no doubt unintended, the nuances in “Nuremberg” set it apart from nearly all other mainstream treatments of the IMT.

“Nuremberg” establishes right away that the German leaders initially did not expect to be charged as criminals for conduct that up until then had been considered normal behavior by governments, and that many of their Allied counterparts considered it distasteful to turn over for trial men such as the charming and witty Göring and the brilliant Albert Speer (Herbert Knaup) who, recent hostilities notwithstanding, are accepted by their captors as honorable men who had served their country capably.

Hermann Göring, the leading German defendant at the Nuremberg Tribunal, proved a formidable figure on the witness stand. In defending himself and the Third Reich's record, his verve, phenomenal memory and quick intelligence were manifest above all in a dramatic duel of wits with Robert Jackson, the chief American prosecutor. Sir Norman Birkett, Britain's alternate Judge at the Tribunal, described Göring's performance under Jackson's questioning: “The cross-examination had not proceeded more than ten minutes before it was seen that he was the complete master of Mr. Justice Jackson. Suave, shrewd, adroit, capable, resourceful, he quickly saw the elements of the situation, and as his confidence grew, his mastery became more apparent.” Brian Cox, the Scottish-born actor who played Göring in the TNT movie “Nuremberg,” remarked: “For the film, we have to see Göring lose it a little, but, in reality, Göring ran rings around Jackson.”

This soon changes, however. Samuel Rosenman (Max von Sydow), former speech writer and confidant of President Franklin Roosevelt, contacts Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson (Alec Baldwin) to convince him to serve as the lead US prosecutor at an “international” war crimes trial, made up of the “four powers” (United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union). After word comes down from on high, the mood turns ugly as the arrests are made, and in a nod toward the widespread but concealed beatings and tortures of German leaders awaiting trial, the movie-makers show Hans Frank (Frank Moore) being pummeled by a gauntlet of Allied soldiers, and finally kicked in the groin after he collapses to the ground.

Jackson’s character is given an interesting wrinkle right off the bat, as he tells his wife that she can’t go because there are “no wives allowed,” yet he takes his secretary, Elsie Douglas (Jill Hennessy). Just in case anyone misses this foreshadowing of Jackson’s eventual intimate relationship with Douglas, she is repeatedly shown gazing at him with what can only be unrequited love. (In the Persico book on which this mini-series is based, she is referred to as “Mrs. Douglas,” and there is nothing about a love affair, as there is no evidence one ever took place.) Jackson is thus portrayed as a noble idealist who is so committed to making the world a better place that he doesn’t have time to worry about trivialities such as keeping the promise he made to his wife on their wedding day.

During the flight to Europe, prosecution liaison Telford Taylor (Christopher Shyer) calls everyone’s attention to the extra-legal nature of their task: “How do we start,” he asks. “There are no precedents, no existing body of law, not even a court.” As the others ignore the import of his question and begin a seemingly arbitrary selection of whom to prosecute, Taylor insists, “I'm still wrestling with the validity of this trial. Crimes committed during war have never been called crimes. To define acts as crimes after they've been committed, even by Nazis – that’s not real law. It’s ex post facto law…. My fear is that at the end of the day, this will be perceived as nothing more than the triumph of superior might – the winners exacting punishment on the losers.” Only a Hollywood film could make Taylor out to be a proto-revisionist!

Once the entourage arrives in Nuremberg, it is clear that even civilian targets in Germany have been bombed relentlessly. Elsie Douglas remembers pre-war photos of the city sent by her brother, and is shocked by the destruction and the stench she encounters. “There are still 30,000 bodies trapped under the rubble,” Eisenhower’s deputy General Lucius Clay informs her. “We're getting disinfectant to counter it.”

On arrival at their jail cells next to the courtroom in Nuremberg, Reichsbank president Hjalmar Schacht (James Bradford) and Field Marshall Wilhelm Keitel (Frank Fontaine) protest their arrest, Schacht and Admiral Karl Dönitz (Raymond Cloutier) denounce Der Stürmer publisher Julius Streicher (Sam Stone) as “filth,” “garbage,” “disgusting,” and “a pornographer and a Jew-baiter,” deftly giving additional depth of character to the accused, where it would be easier to portray them all as malicious and filled with hatred for Jews.

While awaiting trial, the German leaders are kept in what prison psychologist Gustav Gilbert (Matt Craven) tells Nuremberg prison commandant Colonel Burton C. Andrus (Michael Ironside) is a “perfect suicide ward,” where the defendants – with nothing to distract them and little hope of survival – will inevitably attempt to take their own lives. In response, Andrus allows Gilbert access to the prisoners to mitigate the dreariness of their circumstances, on the proviso that Gilbert secretly report back everything he hears.

Like others on the prosecution team, Gilbert is taken aback by Göring’s self-assurance and perspicacity. In many ways, “Nuremberg” is a showcase for Göring, as he moves from strength to strength, rallying the other defendants both before trial and during recess, intimidating Jackson, and at one point, nearly gaining control of the entire proceedings.

Almost from the time they arrive at Nuremberg months before the trial begins, the defendants are shown as expecting to be executed. Cox as Göring uses the “freedom” that comes from knowing his fate to excellent advantage, in contrast to Baldwin’s somewhat wooden portrayal of Jackson, who can do little more than react to Göring. Göring is absolutely certain about who he is, what he stands for, and his place in the world, whereas Jackson is portrayed as barely knowing what he is doing and why he is doing it in Germany, let alone whether he has the commitment to do the job he has taken on. Time after time, Göring passionately rallies his fellow defendants, and trumps Jackson in the courtroom. In desperation, Jackson first moves to limit Göring’s testimony, and ultimately succeeds only after playing the “Holocaust” card, showing footage from the liberation of the western camps (where no one now claims there were any exterminations) and putting Hollywood’s version of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss (Colm Feore) on the stand. As Cox himself acknowledged, “For the film, we have to see Göring lose it a little, but in reality, Göring ran rings around Jackson.” (Los Angeles Times TV Guide, July 16,2000)

“Nuremberg” tacitly acknowledges the tremendous lopsidedness of the proceedings themselves. Jackson is shown in private meetings with the judges, which would certainly be illegal in any jurisdiction in the United States. The prosecutors are shown wallowing in German documents, including Hans Frank’s diaries – which he is certain will exonerate him – while the defense attorneys are virtually invisible, if not impotent. The Allies spare no effort refurbishing the courthouse for the trial, while average Germans starve. These and other straightforward admissions of the grotesquely unbalanced nature of the trials are all the more astonishing if one considers that currently in France, one can be fined and jailed for disputing findings of this court of the victorious.

Perhaps the biggest drawback to “Nuremberg” is that all its teaching and Internet materials support the traditional (anti-revisionist) position. Even so, the inclusion in a TV mini-series of little-known aspects of the shabby post-war treatment of Third Reich leaders is itself proof that the passage of time gives us all a better vantage point on historical events.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 19, no. 3 (May/June 2000), pp. 51-53

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a