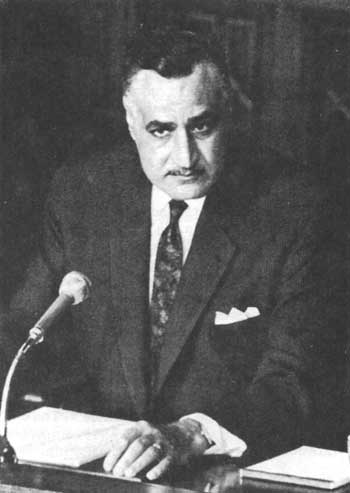

Nasser of Egypt: Deeds and Legacy of an Arab Leader

Donald Neff is the author of several books on US-Middle East relations, including the 1995 study, Fallen Pillars: U.S. Policy Toward Palestine and Israel Since 1945, and his 1988 Warriors trilogy. This article is reprinted from the July 1996 issue of The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs (P.O. Box 53062, Washington, DC 20009).

On July 23, 1952, the corrupt King Farouk of Egypt, an Albanian on his paternal side, was overthrown by a group of young military men calling themselves the Free Officers. The next day, one of the officers, Anwar Sadat, informed the nation by radio that for the first time in two thousand years Egypt was under the rule of Egyptians. Sadat spoke in the name of General Mohammed Neguib, the revolution's titular head. In fact, the real leader was Gamal Abdel Nasser. He was 34 at the time and would rule Egypt for the next 18 turbulent years. Because of his youth, Nasser hid his power behind the older Neguib for the first two years of the new regime. It was not until 1954 that he officially became prime minister, and not until June 23, 1956, that he assumed the presidency.[1]

The coming to power in Egypt of the energetic young warrior sent shockwaves through Britain, France and Israel. Leaders in all three countries feared him as a galvanizing ruler who had the potential to unify the shattered Arab world at the expense of the West and Israel. As Israel's David Ben-Gurion put it: “I always feared that a personality might rise such as arose among the Arab rulers in the seventh century or like [Kemal Ataturk] who rose in Turkey after its defeat in the First World War. He raised their spirits, changed their character, and turned them into a fighting nation. There was and still is a danger that Nasser is this man.”[2]

Britain and France held similar concerns. The rise of a strong Arab leader could not have come at a worse time for both nations. Drained by World War II, they were both in the process of losing their vast colonial empires. Both countries had already lost their mandates in the Middle East and both were desperately trying to maintain their influence in North Africa.

Nasser, above all else, wanted Egypt rid of British troops stationed along the Suez Canal, London's passage to India. In 1954, Britain finally gave in to Nasser's demand and agreed to withdraw its 80,000 British troops since, indeed, there no longer existed any reason for their presence. India was now independent and the canal had lost its strategic importance to Britain.[3] The troops had been there since 1882, and their departure, the last foreign troops on Egyptian soil, was an enormous boost to Nasser's prestige. The historic agreement meant, in British diplomat Anthony Nutting's words: “For the first time in two and a half thousand years the Egyptian people would know what it was to be independent, and not to be ruled or occupied or told what to do by some foreign power.”[4]

Israel, however, was greatly distressed by the agreement. The presence of British troops along the canal acted as a buffer against any rash action by Egypt, Israel's strongest Arab neighbor. Israel was so disturbed by the withdrawal that it had acted directly to ruin the talks by sending a sabotage team to Egypt to attack British and US facilities. However, the covert effort backfired when Egyptian counterintelligence agents captured the spy ring, and the embarrassing mission known as the Lavon Affair became public.[5]

The Anglo-Egyptian Suez agreement, signed in Cairo on October 19, 1954, was widely regarded as a strategic defeat for Britain. Two weeks later, on November 1, Algerian Arabs, their morale boosted by Nasser's success, began their revolt against French colonial rule, which dated back to 1830. One of the many results of the insurrection was to convince France and Britain that Egypt, and specifically Nasser, was aiding the Algerians, and therefore was a dangerous common enemy of the West.[6] France had long seen Israel as a natural ally against the Arabs, and indeed was Israel's major friend at the time. The close friendship included France secretly sending weapons to the Jewish state in violation of the arms embargo agreed to by Western nations, including the United States.[7]

Thus was born the fiasco that has ignominiously gone down in history as the Suez Crisis of 1956. Little remembered in the United States, it was a watershed event in the Middle East. It involved one of the most cynical schemes ever hatched by Britain, France and Israel – and one of the highest points of American diplomacy. It also made Nasser the most idolized Arab leader of his time.

The crisis began when the leaders of Britain, France and Israel decided to collude secretly to get rid of Nasser. Just how to do that was never really clear. But, somehow, they wistfully hoped that by sending vast navies and armies against Egypt they would cause Nasser to be overthrown or to resign in humiliation. The plan was to pretend Israel had been hit by an Egyptian raid, and in retaliation its army would race across the Sinai Peninsula and occupy the east bank of the Suez Canal. In response, Britain and France would pretend to intervene to stop a new Egyptian-Israeli war. All the while, of course, their warships and troops would actually be attacking Egypt. It was a preposterously transparent and shameless ploy but the three nations acted on it nonetheless.

In its broader context, the Suez Crisis was a concerted attack by Europe and Israel against Islam.

A massive armada of French and British warships gathered off Egypt in late summer 1956 as the colluders went ahead amid growing international concern. No one was more concerned than President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The colluders had failed to take him into their scheme, presumably in the mistaken belief that, since they were all US friends, the United States would not oppose their ill-conceived machinations.

In this they were fatally mistaken. Although facing presidential elections in November, Eisenhower publicly and privately opposed the three countries. Using every power short of military force at his command, Eisenhower compelled them to stop their naval bombardment and invasion of Egypt, and to withdraw without gaining any profit from their misadventure. Not only did Nasser not fall, but his prestige soared in the Arab world as the leader who had faced down the West and Israel.

Failure of the Suez plot had disastrous consequences for the colluders. The attack by Britain and France on Egypt drained moral authority from those two countries and spelled the end of their empires. Iraq, Britain's last major ally in the region, fell to Arab nationalists in 1958. And France finally lost Algeria in 1962. After Suez, the United States became the major Western power in the Middle East – not a position President Eisenhower had sought. As he noted in his memoirs, before the Suez war “…We felt that the British should continue to carry a major responsibility for its [Middle East] stability and security. The British were intimately familiar with the history, traditions and peoples of the Middle East; we, on the other hand, were heavily involved in Korea, Formosa, Vietnam, Iran, and in this hemisphere.”[8]

Not only did Britain and France lose their position in the region, but their rash actions helped the Soviet Union cement its presence in such countries as Egypt, Iraq and Syria. Moscow was able to strut as the defender of the Arabs against the perfidious West, earning Russia considerable popular support in the Arab world.

Israel's leaders pronounced themselves satisfied with the gains achieved. It had secured US support for free maritime passage through the Strait of Tiran, connecting the Red Sea with the Gulf of Aqaba and the Israeli port of Eilat, and the stationing of [United Nations] UNEF troops at Gaza, where they prevented fedayeen [guerilla] raids into Israel. Prime Minister Ben-Gurion thought he had profited by humiliating Nasser and by raising domestic morale and intensifying a sense of national identity among Israel's diverse Jewish population. However, on closer examination Israel had sowed the whirlwind with its aggressive actions. The government of Gamal Abdel Nasser had initially shown little interest in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Its main interests were narrowly focused on its own demanding domestic problems. But after Israel's aggressive actions, which started well before the Suez outrage, Egypt diverted its resources to a major buildup of its armed forces.

The war also released aggressive forces within Israel that fed on dreams of conquest and expansion. These dreams would be realized eleven years later when Israel launched another surprise attack against both Egypt and Syria, drawing in Jordan, which was bound to both Arab countries by military treaty. That aggression, in turn, made Israel a pariah state in the world community because of its continued occupation of Arab land, and made inevitable the 1973 war, which cost Israel unrelieved suffering and shook the country's self-confidence to the core. By then Nasser was gone. He had died of a heart attack on September 28, 1970, at the age of 52.

Although widely reviled by Israel and its supporters, Nasser, the son of a postal clerk, had been a great Arab leader. While he was a compulsive conspirator, suspicious of others and thin-skinned to criticism, he was also charismatic, a natural leader and eventually the most beloved and admired Arab of his time. Nasser was described by his friend and chronicler, Mohamed Heikal, as “always a rebel [who] remained a conservative in his personal life… He was never interested in women or money or elaborate food. After he came to power the cynical old politicians tried to corrupt him but they failed miserably. His family life was impeccable… The world itself had found in him one of its most controversial statesmen and the Arabs had chosen him as the symbol of their lost dignity and their unfulfilled hopes.”[12]

In the judgment of diplomat Anthony Nutting, who knew Nasser and wrote a biography of him: “For all his faults, Nasser helped to give Egypt and the Arabs that sense of dignity which for him was the hallmark of independent nationhood… Egypt and the whole Arab world would have been the poorer, in spirit as well as material progress, without the dynamic inspiration of his leadership.”[13]

Notes

| [1] | Anthony Nutting, Nasser (London: Constable, 1972), p. 37; Richard F. Nyrop, et al., eds., Area Handbook for Egypt (Washington, DC: US Govt. Printing Office, 3rd ed., 1976), p. 36. The best biographies of Nasser remain those of Nutting and Stephens: Anthony Nutting, Nasser (London: Constable, 1972), and, Robert Stephens, Nasser: A Political Biography (London: Allen Lanel/Penguin Press, 1971). |

| [2] | Kennett Love, Suez: The Twice-Fought War (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1969), p. 676. |

| [3] | Anthony Nutting, Nasser (London: Constable, 1972), pp. 69-72; Donald Neff, Warriors at Suez: Eisenhower takes America into the Middle East (New York: Linden Press/Simon & Schuster, 1981), pp. 17-18, 59. |

| [4] | A. Nutting, Nasser (London: 1972), p. 71. |

| [5] | D. Neff, Warriors at Suez: Eisenhower takes America into the Middle East (New York: 1981), pp. 56-58. |

| [6] | D. Neff, Warriors at Suez (New York: 1981), p. 161. The bitter war lasted until July 1, 1962, when Algerians voted to establish an independent Arab nation. The fighting took the lives of 17,456 French, and upward of a million Arabs. See: Alistair Horne,A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962 (New York: Viking, 1977), p. 538. |

| [7] | D. Neff, Warriors at Suez (1981), pp. 235, 238. |

| [8] | Dwight D. Eisenhower, Waging Peace: 1956-61 (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1965), pp. 22-23. |

| [9] | [Footnote is missing in the original JHR text; ed.] Cheryl A. Rubenberg, Israel and the American National Interest: A Critical Examination (Chicago: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1986), p. 84. |

| [10] | [Footnote is missing in the original JHR text; ed.] D. Neff, Warriors at Suez (1981), p. 439. |

| [11] | [Footnote is missing in the original JHR text; ed.] K. Love, Suez: The Twice-Fought War (New York: 1969), pp. 13-14. |

| [12] | Mohamed Heikal, The Cairo Documents (New York: Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1973), pp. 1,20. |

| [13] | A. Nutting, Nasser (1972), p. 481. |

'No One' Believes the 'Six Million'

In spite of endless repetition, millions of people around the world have never believed the figure of Six Million Jewish wartime victims. In a 1964 interview, Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser said that “No one, not even the simplest man in our country, takes seriously the lie about six million murdered Jews.”

—(Source: Interview with the Deutsche (Soldaten und) National-Zeitung [Munich], May 1, 1964, p. 3. Also, quoted in part in: Robert S. Wistrich, Hitler's Apocalypse [New York: St. Martin's Press, 1986], p. 188.)

Forces of the Future

“Little as we know about the events of the future, one thing is certain: the moving forces of the future will be none other than those of the past – the will of the stronger, healthy instincts, race, will to property, and power.”

—Oswald Spengler, Die Jahre der Entscheidung.

“Few men have virtue to withstand the highest bidder.”

—George Washington

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 18, no. 3 (May/June 1999), pp. 36-38; reprinted from The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, July 1996.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a