The Report of the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission on the Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp

The Genesis of a Propaganda Project

The “Extraordinary State Commission” (ESC, from Russian ЧГК, an acronym for Чрезычайная Государственная Комисссия) was created in November 1942 in order to detect and investigate “crimes perpetrated by the German Fascist Invaders” and the damage caused by them. After the Red Army had reconquered Soviet territories previously occupied by the Germans, this commission became very active on all local levels, including the most remote villages. Tens of thousands of witnesses were questioned, and in important cases reports based on the pertinent testimony were drawn up in Moscow. Many of these reports were then published in Pravda, thus acquiring the status of official Soviet documents. During the Nuremberg trial more than 500 ESC reports were submitted to the court as incriminating evidence and registered as “USSR documents”. Still today these documents profoundly condition the presentable view of “German war crimes in Eastern Europe” and “atrocities committed in National Socialist concentration camps”.

After the collapse of the communist system in the Soviet Union the ESC became itself an object of historical investigation within and by the successor Russian state. In the meantime it has become increasingly clear that this commission was essentially an instrument of the domestic and foreign policy of the Stalin regime. It had been established to support Soviet war and atrocity propaganda and to heap massive blame on the “German Fascist invaders”, regardless of historical truth. For this reason, the ESC reports are a highly unreliable source; historians should use them with the utmost caution. But in the past, they have passed, under “law,” for fact, and they continue to be cited as such by those whose agendas are served by their content.

The present paper was inspired by an accidental discovery the author made in the Russian State Archives (GARF) where he stumbled over the drafts of an ESC report about Sachsenhausen concentration camp. These drafts date from 1945, but no report was ever published. Comparisons among the different versions enables us to understand the genesis of this type of report.

1. The ESC – an Instrument of the Domestic and Foreign Policy of the Stalin Regime

On 2 November 1942 the “Extraordinary State Commission” (ESC) was set up by a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. It had the responsibility to “detect and investigate the crimes of the German Fascist Invaders and their accomplices as to the damage they had inflicted on citizens, collective farms, public organizations, state enterprises and institutions of the USSR.” On 4 November 1942 Pravda announced the creation of this commission on its front page.

The ESC was nominally headed by ten prominent Soviet personages (politicians, scientists, academicians etc.) under the leadership of communist functionary N. M. Chvernik. In fact, these ten famous persons were little more than figureheads whose signatures were needed to give the reports of the commission the necessary prestige. The real work was done by an office which had at its disposal a staff of about 150 workers (approximately as many as a small Soviet ministry). More than 100 subcommissions were active on all local levels – from the Soviet Republic to the Oblast (Province), Kraj (Territory) and Rayon (District), from the big cities to the most remote villages. Local commissions were usually headed by a Troika consisting of the First Party Secretary, the Representative of the Government and the chief of the NKVD (the Soviet Union’s CIA). On all levels the work of the commissions were directed and coordinated by the NKVD and the counterintelligence agency SMERSH (acronym for СмертьШпионам, ”Death to the Spies“).

As soon as a given area had been reconquered by the Red Army, the local commission set to work. Apart from ascertaining the extent of the war damage and the war crimes imputed to the Germans, the commissions had the additional task to identify the parties to be blamed, i. e. members of the Wehrmacht, the SS and the Einsatzgruppen of the SD. Another prime target were the ”accomplices of the henchmen“ – local residents (styled “Soviet citizens”) who had in one way or another collaborated with the occupiers. At least one of these reports – the one about Katyn (in which the perpetrators were the Soviets themselves) – was translated into English and diffused in the USA and Britain. During the Nuremberg trial, more than 500 ESC reports were submitted to the court as incriminating evidence. After the collapse of the communist system in the USSR, the microfilms of numerous secondary ESC documents (interrogation protocols, eyewitness testimony, etc.) were acquired by various archives in the West. Since the end of the Second World War, the material of the ESC has profoundly influenced the acceptable view of the “Nazi crimes” in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. Both in the East and in the West, numerous historians have uncritically regarded these documents as a credible historical source, while others have always viewed them with considerable skepticism.

Whereas at least the most important ESC reports have been generally accessible since the Nuremberg trial, very little has been known about the commission itself, its staff, its hierarchical structure etc.. Only recently has it become possible to throw light on some aspects of this shadowy organization. The ESC used conspiratorial methods; it could easily have been set up as a special branch of the NKVD, but in view of the sinister reputation the NKVD “enjoyed” beyond the Soviet borders, the Kremlin chose a different line of action. Recently, several researchers have pointed out that the reports of ESC are an utterly unreliable source of historical information. In this context, the pioneering work of American historian Marian Sanders[1] and an article by Russian historian Marina Sorokina, which gives an excellent survey of the question[2]are of particularly high value.

ESC had a significant role as an instrument of the foreign and domestic policy of the Stalin regime. Its statistics about the horrendous material damage the USSR had sustained during the war enabled the Soviet State to claim massive reparations. The monstrous atrocities imputed to the “German Fascist invaders” kindled the hatred of the Soviet soldiers and the civilian population against the German enemy and strengthened their fighting spirit. After the end of the war, the reports of the ESC formed the basis of the accusation against German “war criminals” at Nuremberg.

New findings suggest that the ESC was entrusted with other delicate tasks as well. In this connection the cases of the Katyn Forest Massacre and Vinnitsa are highly suggestive. After the great Stalinist purge (1936-1939) the Soviet Union was littered with secret mass graves where the victims of the NKVD were buried. In spring 1940, when the USSR was not yet allied with the western powers, about 15,000 Polish officers were murdered by the NKVD in compliance with an order from the Soviet government. Approximately one third of these men were shot and buried in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk.

Thanks to hints from the local populace, the mass graves of Katyn were discovered in February 1943 when the area was occupied by the Germans. Some three months later, in May 1943, mass graves dating from the Soviet period were found at three places near the Ukrainian city of Vinnitsa. In April 1943 the Germans began opening the Katyn graves; more than 4,000 corpses were exhumed before the action had to be interrupted because of the summer heat. Several commissions consisting of forensic experts, criminologists, journalists and politicians from neutral and German-controlled countries were invited to inspect the site of the massacre. Katyn was also visited by members of the Polish Red Cross, whereas the International Red Cross in Geneva had declined the German invitation under Allied pressure. The Wehrmacht took captured American, Canadian and British officers to Katyn so that they could witness the evidence of what had transpired there. The government of the Reich published the results of the investigations in a “White Book.”[3]

For the Soviet rulers the discovery of the Katyn mass graves was terribly embarrassing. In order to save face, they accused the Germans of having committed the crime themselves. As early as September 1943 the area around Katyn was reconquered by the Red Army. This provided the Soviets with an opportunity to draw up their own “forensic report”. As they imputed the massacre to the Germans, it was only logical that the ESC was entrusted with the new investigation. The local commission re-opened the mass graves, performed autopsies of the corpses, interrogated intimidated local citizens and German prisoners of war and then published the results of its findings in a report. Compared with the overwhelming evidence found by the Germans, the Soviet “proofs” were rather meager, so that they had to be extensively reinforced by ”eyewitness reports“ (a well-tried method). To nobody’s surprise, the commission concluded that the mass murder had been perpetrated by the “German Fascist invaders”.

The report of the “Special Commission for the Examination and Investigation of the Circumstances of the Shooting of Captive Polish Officers by the German Fascist Intruders in the Katyn Forest”, dated “Katyn, 24 January 1944” was at once published in Pravda. It is now universally acknowledged that this document, which was among the first and most important of the 27 officially sanctioned ESC reports, blatantly distorted the facts: On 13 April 1990, the forty-seventh anniversary of the discovery of the mass graves, Moscow finally admitted Soviet secret-police responsibility.

Concurrently with the publication of the Katyn report in Pravda, an English translation was published in the USA and later presented at the Nuremberg trial[4] as definitive “evidence” for the German responsibility (“Document USSR-54”). However, the defendant Göring and his defense counsel were able to counter this accusation with such powerful arguments that the court tacitly dropped it. The spectacular case of Katyn clearly demonstrated that the Soviets did not shrink from putting the blame for their own crimes on the Germans. In this particular case the Soviet tactic could easily be explained by the predicament Moscow was facing: As the Soviets could not possibly admit their guilt, they by necessity had to blame their German adversary. But Katyn did not remain an isolated case. Wherever it seemed opportune, mass graves containing the bodies of victims of pre-war purges were ascribed to the Germans. For this tactic, Marina Sorokina has coined the apt term “Katyn model”. The organization in charge of this brazen falsification was the ESC.

In Vinnitsa, Ukraine, the occupying Germans found altogether 91 mass graves at three different places situated on the outskirts of the city (the graveyard, the orchard and the public park). In the period between July and 1 November 1943 all of them were completely emptied, and 9,432 bodies were exhumed. As had been the case at Katyn, medical experts, journalists, clergymen etc. were invited to Vinnitsa so that they could personally see the evidence. Once again, the results of the investigations were thoroughly documented in a German “White Book”[5]. In spite of the overwhelming evidence, the Soviet propaganda again accused the Germans, but Vinnitsa soon disappeared from the headlines. In March 1944 the city was re-conquered by the Red Army.

In the West the Vinnitsa massacre became a non-issue after the war. At Nuremberg the Soviet prosecution refrained from bringing up the case. As C. Mattogno and J. Graf have pointed out[6], Vinnitsa was mentioned but once during the whole trial; the Bulgarian witness prof. Markov named the city in connection with the exhumation of bodies. From the Soviet point of view this was a minor embarrassment.

After the German retreat from Vinnitsa, the ESC immediately set to work and drew up the usual report[7] in which the commission made the unsubstantiated claim that “no fewer than 41,820 peaceful citizens and prisoners of war had been put to death during the German occupation”. The report made no reference to the mass graves containing the remains of 9,432 victims of the Soviet regime which had been exhumed in 1943.

2. Investigations Carried out by the ESC in the German Concentration Camps

On 23 July 1944, the Red Army captured the first German concentration camp, Majdanek. Other camps followed: Auschwitz (27 January 1945), Gross-Rosen (mid-February 1945), Sachsenhausen (23 April 1945) and Stutthof (9 May 1945). In addition to these large camps, several small ones – such as the forced-labor camp Lemberg-Janowska Street – fell into the hands of the Soviet forces. In order to report what had transpired in these camps, the ESC had each of them examined by a sub-commission consisting of medical experts, physicians, engineers etc. who had been recruited from among the “operatives” of the Ministry of Domestic Affairs (NKVD) present in all units of the Red Army.

The local commissions then forwarded the results of their investigations to their superior, the ESC in Moscow. Based on the material received, the ESC then drafted a report about the respective camp. Many such reports were used as incriminating evidence at the Nuremberg trial, e.g. IMT document USSR-8 about Auschwitz and IMT document USSR-29 about Majdanek. Majdanek was the only camp any western journalists were invited to; the only journalist admitted to Auschwitz was the renowned Red Army reporter Boris Polevoi who subsequently wrote his well-known article about the “Death Factory”[8]. No journalists, neither Russian nor foreign, were admitted to the other concentration camps captured by Soviet forces.

By order of the ESC, a special commission led by a representative of Soviet military justice, Lt. Colonel A. Sharitch, carried out extensive investigations in the former concentration camp Sachsenhausen (May/June 1945). The commission was subdivided into several working groups, the activities of the so-called ”Technical Commission“ which inspected the camp crematorium (now called ”Station Z”) being of particular interest. The reports of these working groups, as well as Sharitch’s final report, are now kept at the State Archives of the Russian Federation (GARF).

Yet another “special commission,” to investigate the Sachsenhausen camp, was created in Moscow. It consisted of three members of the ESC office (General D. I. Kudryavzev, P. V. Semjonov and P. T. Kusmin), two representatives of the public prosecutor’s office (P. I. Tarasov-Rodyonov and P. V. Baranov) and a representative of the NKVD (A. I. Simenkov). Kudryavzev had already acquired considerable experience at Auschwitz, where he had headed the local ESC commission; the well-known document USSR-08 was probably finished at the time the Sachsenhausen commission was set up. Kudryavzev’s colleagues Semyonov and Kusmin were ordered to write an equivalent report about Sachsenhausen. We may safely assume that it was planned to present this report at Nuremberg together with the ones about Majdanek and Auschwitz, but for reasons which will become clear later this was not the case[9]; the document was never published or used as incriminating evidence against the “German Fascists”. At the State Archives of the Russian Federation (GARF) the author has found several drafts of the planned report, plus some letters concerning the same subject. An analysis of these documents provides us with a unique insight into the way such reports originated; it shows how the Soviet picture of the history of the camp came about and how the commission handled the results of its own “investigation”.

3. The “Brown Portfolio”

Upon receiving the reports of the various working groups, Lt. Colonel A. Sharitch produced the final version[10], whereupon he probably forwarded the entire body of material to his superiors. The ESC in Moscow then began drafting an official report about Sachsenhausen. The respective drafts and the correspondence about this subject are now bound in a brown Portfolio made of imitation leather[11] so they stand out amid the mass of “ordinary” Sachsenhausen material at GARF where the author of this article discovered them several years ago. The documents supply no information about the origin of the drafts. The Soviet administration did not normally use official stationery with a pre-printed letterhead, as was common practice in Germany, Britain, and other countries. In the specific case discussed here this may have been due to the fact that the sender and the addressee were residing in the same building, the house of the Sovnarkom (Council of People’s Commissars). Most drafts lack any reference to the author and the date and bear no signature. Only rarely do the documents bear a handwritten date, and even in these cases it is not clear what the date refers to. Sometimes we find a register number, which is rather difficult to interpret owing to our ignorance of the system used. The handwritten, continuous pagination of the archives only adds to the confusion because it does not square with the chronology of the events. In other words, for the researcher this Portfolio is a real nightmare. The chaos is probably due to the fact that in 1951, after the dissolution of the archives of the ESC, the material was handed over to the Central Archives of the October Revolution (now GARF) without previous rationalization.

When producing a report, the ESC apparently proceeded as follows: It sent its draft to the vice president of the Council of People’s Commissars (Deputy Prime Minister) of the USSR, Andrey Vyshinsky[12], who actively participated in the styling of the text, regularly demanding minor or radical modifications. Vyshinsky thus became the “grey eminence” of the ESC, its “unofficial chief editor and censor” (Sorokina). Only when a report met with his full approval was it forwarded to Foreign Minister Molotov (usually by Chvernik, the nominal head of the commission). The final decision as to the publication of an ESC report was up to Stalin.

This pattern clearly emerges in the case of the Sachsenhausen report. When Vyshinksy desired changes in the text, he sometimes contented himself with marginal notes, but in most cases he may have summoned ESC secretary Bogoyavlensky to notify him of his wishes. The reasons which motivated the substantial modifications of the contents of the reports remain undocumented. The ESC used conspiratorial methods; delicate topics were in all likelihood discussed orally, and it is quite probable that even among themselves the members of the commission rarely used plain language.

4. Chronology of the Drafts

The ESC in Moscow probably began drafting its own report as early as in July 1945, immediately after receiving the reports from Sachsenhausen. Whatever his other talents may have been, Semyonov was not exactly a literary genius; his various drafts virtually cried for improvement. The fact that his report about a complex subject – a large concentration camp – was not even subdivided into sections shows that he was unable to present the topic in a logical and systematic way. While the fate of seven British sailors was discussed in great detail on several pages, only a few lines were dedicated to the 14,000 Soviet POWs (allegedly) shot at Sachsenhausen. These glaring shortcomings can perhaps be explained by the fact that Semyonov first wanted to feel out the wishes and intentions of his superiors because delicate questions were not discussed openly.

To cut a long story short: There are no fewer than six drafts, which we will call “Shn-1”, “Shn-2”, “Shn-3”, “Shn-4”, “Shn-5” and “Shn-6” (Shn = Sachsenhausen). Of the four “complete” drafts, we have translated but two; as to the others, a comparison of the texts was sufficient to recognize differences and deviations and to reconstruct the chronological order of the documents. Two examples will suffice to illustrate this point. In drafts Shn-1, Shn-2 and Shn-3 the Cyrillic transcription of Sachsenhausen is correct (“Саксенхаусен” ), while in Shn-4A to Shn-4C the name of the camp is misspelled as “Саксенгаусен”, the German “h” being erroneously rendered as “r” instead of “x”. The person who styled Shn-4D then realized this error and corrected it manually. In Shn-4 and Shn-6 the wrong letter “г” does not occur any more; it has been replaced by the correct “х”. Another detail which greatly helped us to establish the chronology of the documents is the enumeration of the nations whose subjects had been interned at Sachsenhausen. As the order in which these nations were enumerated reflected the esteem the respective countries enjoyed in Moscow at the time the reports were written, it was constantly changed – which enabled us to draw certain conclusions as to their chronology.

4.1 The first draft (Shn-1)

Based on the reports from the Special Commission in Sachsenhausen (a quarter in the town of Oranienburg north of Berlin), a first draft was composed (probably still in the camp itself). A copy of this document has survived (it is not kept in the aforementioned “Brown Portfolio”, but in another file).[13]

Winfried Meyer assumes that this draft originated in June 1945[14], but as it was written after Sharitch’s final report, which was dated 29 June 1945, the correct month is probably July 1945. Unlike most other drafts, Shn-1 bears two signatures (D. Kudryavzev and P. Semyonov). In all likelihood P. Semyonov was the real author of the text, which his superior, general Kudryavzev, simply approved by his signature). The heading has been made illegible by hand. The document is undated. It consists to a great extent of excerpts from the reports of the various subcommittees which had been active in Sachsenhausen, plus Sharitch’s final report.

4.2 Shn-2

The content of the corrected draft Shn-2[15], which differs from the other drafts by its narrower typeface, is largely identical with Shn-1. It was probably finished by mid-September 1945 and then forwarded to Malenkov and Vyshinsky (Shn-2A and Shn-2B).[16] It is undated, not subdivided into chapters and bears neither heading nor signature.

4.3 Shn-3

Shn-3[17] is obviously a new finished copy of Shn-2. This third version appears under the headline “REPORT of the Special Commission for the investigation of the crimes of the German Fascist Occupiers in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.” A subdivision into chapters is still lacking; the number of pages (eleven) remains unchanged. This time General Kudrjavzev is the only signer.

4.4 Shn-4

Probably because Vyshinsky had orally ordered certain changes to be made, the text was again revised and a new finished copy was produced (Shn-4). For the first time the eleven pages are subdivided into chapters. The draft Shn-4 exists in four different copies which we call Shn-4A, Shn-4B, Shn-4C and Shn-4D. The typewritten manuscript is identical in all four copies, but the texts were altered by handwritten additions and corrections.

4.5 Shn-4A

Shn-4A is a finished copy[18] (without corrections) and the only of the four versions which is signed. The first signer (illegible) added the date (26. IX. 1945); the second one was apparently Semyonov, as a comparison with Shn-1 suggests. Finally the document was signed by a superior, most probably Kudryavzev.

4.6 Shn-4B and Shn-4C

Shn-4B[19] is equally a finished copy, apparently an unused reserve copy (this is suggested by the fact that there is neither signature nor date and that no corrections whatsoever were made). Unlike Shn-4B, Shn-4C[20] presents some insignificant corrections and cuts.

4.7 Shn-4D

The typewritten manuscript of this copy[21] is identical with the preceding ones, but the handwritten pagination of pages 1-11 is highly chaotic (p. 94, 99, 100, 101, 109, 106, 107, 108, 110, 111, 95). As the numerous changes, additions, cuts, rearrangements and insertions show, the text was drastically modified. It emerges from a later accompanying letter that these modifications were made by Kudryavzev’s superior Bogoyavlenski, the responsible secretary of the ESC, in compliance with Vyshinksy’s instructions. The document Shn-4D is basically the rough draft of a new report the definitive version of which was to be Shn-6. Shn-4D bears the handwritten date 29. IX. 45, which means that it was drafted only three days after Shn-4A. The trial of the “main war criminals” in Nuremberg was scheduled to commence on 20 November 1945. Apparently the authors of the Sachsenhausen report were pressed for time.

4.8 Shn-5

This version consists of a mere four pages[22] which were obviously meant to complete the chapter “The annihilation of the prisoners of war”. The text begins at page 7/2 with the so-called Ziereis confession. It was integrated into the final version Shn-6 without any changes.

4.9 Shn-6

This document[23] is the finished copy of the version Shn-4D enlarged by the fragment Shn-5 (illustration 1). The size of Shn-4 plus the subdivision into chapters, remain unchanged. Date and signature are lacking. We may safely assume that Shn-6 was the final version presented to Vyshinsky by the office of the ESC. As the preceding draft (Shn-4D) is dated 29. IX. 45, Shn-6 was most probably finished in early October 1945. The heading reads: “Report of the Extraordinary State Commission for ascertaining and investigating crimes perpetrated by the German Fascist Invaders. About the annihilation of citizens of the USSR, England, France, Poland, Holland, Belgium, Hungary and other states by the German authorities at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.”

Altogether the chaotic “Brown Portfolio” contains four “finished” fair copies of drafts: Shn-1, Shn-3, Shn-4A and Shn-6. The last draft Shn-6 was apparently approved by Vyshinsky and finally presented to foreign minister Molotov.

5. The Contents of the Drafts: A Comparison

5.1 The Number of Transportable Crematory Ovens

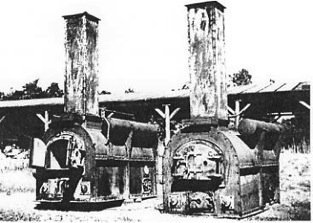

Since 1940 the Sachsenhausen concentration camp had been equipped with a small crematorium consisting of two one-muffle ovens the combined capacity of which probably did not exceed 14 cremations per day.

In preparation for a sustained program of execution of selected Soviet prisoners of war (the so-called “Russenaktion”) in fall 1941 the camp acquired some “field crematoria” (very compact ovens which were reinforced by an iron frame and therefore transportable). These ovens used oil as combustible; the necessary temperatures could be reached fairly quickly, and in case of necessity the ovens could be operated around the clock. As can be deduced from their name, these ovens had been developed for use near the front or in areas contaminated by epidemics. Soviet post-war propaganda made great fuss about the mobility of these ovens; they were, so to speak, the equivalent of the “mobile gas chambers” – the “gas vans”.

During the “Russenaktion” the field crematoria were deployed in the immediate neighborhood of the shooting barracks and surrounded by a high paling to conceal them from curious eyes. The crematoria and the paling are sometimes called “provisional crematory”. The shooting barracks and the field crematoria were situated at the “North Yard” of Sachsenhausen, a quiet, isolated sector of the camp where only a handful of prisoners were assigned.

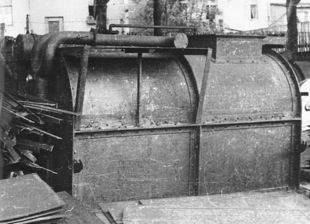

Significantly even the elementary (but important) question of how many such ovens existed at Sachsenhausen has not been clarified up to the present day. The only undisputed fact is that at the end of the war two field crematoria were found in the camp, where they were standing under a shed roof surrounded by all kinds of trash (Illustration 2).

Photograph: Soviet investigation team, May/June 1945.

Photograph: Soviet ”Fact-finding commission“, May/June 1945.

Source: The film “Todeslager Sachsenhausen“, DEFA 1946.

These ovens were probably retired after the new crematorium had been put into operation in May 1942 (illustration 3).

How many field crematoria were used during the “Russenaktion” remains unclear. According to the crematorium worker Paul Sakowski there were altogether four ovens. Two of them were reportedly sent to other camps during the war. The film “Todeslager Sachsenhausen” (“Death camp Sachsenhausen”) (1946) shows the two remaining field crematoria which had in the meantime been moved to the open air. Apparently there were no more such crematoria in Sachsenhausen in 1945, otherwise the Soviet investigators or the film crew from DEFA[24] would undoubtedly have set up them in a row (illustration 4).

According to the first draft Shn-1[25] there were four mobile (transportable) crematorium ovens:

“In order to erase the traces of their bloody crimes the camp administration set up four mobile crematoria ovens which were mounted on trailers [smontirowannyje na awtopritsepach]. The chief of the mobile crematorium was Hauptscharführer Klein under whose supervision the corpses of prisoners who had been shot, hanged or tortured to death were incinerated.”

With some minor modifications, these sentences occur in all later drafts[26]; however the claim that the ovens were “mounted on trailers” was abandoned after Shn-4B. It should be pointed out that the figure of four transportable crematoria does not square with the so-called Technical Report of Soviet engineers Blokhin, Telyaner and Grigoryev.[27] While the authors of the report fail to mention the number of ovens, their calculation of the cremation capacity is based on three transportable ovens. [28] The ESC in Moscow did not take exception to this contradiction; maybe nobody had even noticed it.

In the meantime the propagandists in Moscow had become aware of the so-called “Ziereis confession” – the protocol of an interrogation of the former commandant of Mauthausen concentration camp, SS-Standartenführer [Lt. Colonel] Franz Ziereis who was questioned by the Americans before his death. The interrogation took place in the hospital of the satellite camp Gusen on 24 May 1945.[29] Ziereis, who according to the minutes had been “wounded by two shots in the belly and the left arm” was lying on a camp bed which was to become his deathbed as he was denied medical assistance (illustration 5, illustration 6). The minutes state that Ziereis had fled to a hunting lodge near Spital am Phyrn (Traunviertel/Upper Austria) where he was tracked down and wounded by US soldiers. According to other reports he wanted to surrender the camp on 8 May 1945 whereupon he was shot without the slightest provocation. All reports about the arrest and the shooting of Ziereis and about the circumstances of his interrogation on his deathbed are contradictory and unreliable; fundamental questions remain unanswered.

Source: Memorial Gusen.

According to the minutes Ziereis began his testimony as follows:

“On 23 May 1945 at 18 o’clock, while fleeing, I was wounded by American soldiers near the lodge at Pyhrn near Spittal. My name is Franz Ziereis; I was born on 13 August 1905. I was the commandant of Mauthausen concentration camp and its satellite concentration camps. While trying to escape, I was wounded by gunshots in my left upper arm and in the back. A bullet pierced my belly and my abdominal wall. I was taken to the 131st evacuation hospital (US Army hospital) at Gusen and wish to make the following statement […].”

Source: Memorial Gusen.

These photographs clearly show that Ziereis was hardly able to make the lengthy statements ascribed to him. Most likely the “minutes” were written after his demise by the former Mauthausen inmates Marsalek and/or Pienta. Some of Ziereis’s alleged statements are so outlandish (he claimed that no fewer than 1.5 million people had been gassed at Hartheim Castle!) that he cannot possibly have made them. In all likelihood his account of a meeting of all concentration camp commandants which allegedly took place in Sachsenhausen was added after the event, perhaps thanks to a “hint” from the Soviet operatives in Berlin.

In the Paris-based documentation center of the Allied powers the minutes of the ”Ziereis confession” were registered as document 1515-PS.[30] However, this document does not appear in the IMT volume where one would expect to find it according to its number. The original is probably rotting in some unknown American archive. During the Nuremberg trial, a German translation was made for the benefit of the defense counsel; the text can be found in the German version of the trial documents. It is dated “Mauthausen, 24 May 1945”. The interrogation began at 9:15 o’clock and was interrupted “on 24 May 1945, 14.00 o’clock owing to the weakness of the subject”. The minutes of this interrogation, which had lasted nearly five hours, consist of only four pages. The second part of the interrogation – we are not told when it started and how long it lasted – has no fewer than 17 pages (in the German translation). It contains an enumeration of the 33 satellite camps of Mauthausen and the number of their inmates, detailed information about various occurrences and a letter from Ziereis to his wife. There can be little doubt that the bulk of these minutes was added after the event. A look at the German translation shows that, except for the date, the minutes are lacking all the data usually present in this type of document: The names of the interrogators, the keeper of the minutes, the interpreter and the minor witnesses. So much for the credibility of the “Ziereis confession”.

In its drafts Shn-5 and Shn-6, the ESC extensively quotes from this highly suspect document.[31] Ziereis allegedly described a meeting of the German concentration camp commandants at Sachsenhausen, where a new “neckshot facility for Politruks and Russian commissars” was demonstrated. According to Shn-6, Ziereis made the following comment on the shooting of Soviet POWs at Sachsenhausen (“Russenaktion”):[32]

“8 mobile crematoria were constantly in operation opposite the corpse building [the alleged shooting barracks]. Every day 1,500 to 2,000 people were being killed.”

So while the authors of the Technical Report spoke of three mobile ovens, and while the first draft Shn-1 mentioned four of them, their number had grown to eight in the final version Shn-6, which means that the capacity of the crematoria had again been doubled, at least on paper. At that time the ESC in Moscow claimed that no fewer than 100,000 prisoners had perished at Sachsenhausen. [33] As no mass graves had been detected, this implied that the bodies of the victims had been cremated, which was only possible if the capacity of the ovens had been up to this task. It should be borne in mind that in the German translation of the “Ziereis confession” the number of ovens is not mentioned; the only information about the crematoria reads as following:

“Opposite the corpse room two crematoria were constantly in operation. Their daily capacity probably fluctuated between 1,500 and 2,000 prisoners. It is my guess that this procedure continued for at least five weeks. For example, when the commandants came the crematoria had already been in operation for 14 days.”

So the only witness the ESC relied upon and its reconstruction of the events which had preceded the “Russenaktion” was the late Ziereis, although the commission could easily have questioned some members of the former Kommandantur Staff of Sachsenhausen. At that time most of them were already in (British, not Soviet) custody, so they could have confirmed – or denied – Ziereis’s statement about the alleged meeting of the concentration camps commandants in July 1941. Significantly, no statements made by these SS officers in British custody have been published up to the present day.

5.2 The Capacity of the Crematoria Ovens

As to the capacity of the crematoria ovens, Semyonov, the author of the first draft (Shn-1), relies upon the Technical Report, which implied that there had been three transportable ovens, although only two had been found:[34]

“The cremation of six bodies in the ovens of the mobile crematorium required 30 minutes, which meant that 864 bodies per day could be incinerated if the three ovens were in operation around the clock.”

Based on this (insanely exaggerated) figure, Semyonov calculated the alleged maximum capacity of the transportable ovens during their entire existence. Without any explanation he postulated that these ovens had been in operation from September 1941 until March 1943, to-wit, approximately 570 days. He thus came to the following conclusion:[35]

“A. In the transportable crematoria ovens [864 x 570 =] 492,480 bodies could be cremated from September 1941 until March 1943.”

But the experts did not content themselves with this absurd exaggeration. With regard to the capacity of the four stationary one-muffle ovens of Sachsenhausen, the Technical Report stated:

“B. The crematoria ovens were designed for uninterrupted operation. Four to six corpses could be simultaneously introduced into one oven. The necessary time for the cremation of six corpses in one oven was 60 minutes. Within twenty-four hours [6 x 4 x 24 =] 576 corpses could be disposed of.”

As in the case of the mobile ovens, the alleged capacity of the stationary ones was heavily inflated. Semyonov arbitrarily assumed that the latter ones had been in operation from March 1943 until April 1945 (about 750 days) and thus concluded:

“3. In the stationary crematorium [576 x 750 =] 432,000 corpses could be incinerated from March 1943 until April 1945.”

Based on the (alleged) capacity of all ovens (1 oven = 1 muffle) Semyonov claimed:

“In consideration of the fact that the Hitlerites not only annihilated prisoners of the [Sachsenhausen] camp, but that transports with prisoners from other concentration camps arrived there – from Majdanek, Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, Mauthausen, Ravensbrück etc. as well as from various European countries occupied by the Germans – the Hitlerite henchmen could cremate 924,480 people at the [Sachsenhausen] camp, as results from the Technical Expertise.”

Let us resume: The Soviet investigators postulated that the field crematoria could incinerate 288 bodies per muffle per day, while the stationary ovens could cremate half this number – 144 bodies per muffle per day; both types of crematoria were allegedly in operation around the clock. In both cases, the alleged capacity was about 20 times higher than the real one (even of modern crematoria). The Soviet experts could not possibly ignore the fact that the postulated figures were completely unrealistic. For reasons of space, we cannot enumerate all the tricks, wrong insinuations and incorrect assumptions the aforementioned data are based upon, so we will confine ourselves to the most glaring incongruities:

i. The Number of Portable Ovens

As we have mentioned before, the statements about the number of transportable field crematoria fluctuate between two and eight. The experts Telyaner, Blokhin and Grigoryev assumed that there were three such ovens.

ii. The period of operation of the new crematorium

In his first draft (Shn-1) Semyonov insinuated that the four stationary ovens of the new crematorium had been in operation “from March 1943 until April 1945”. This claim was incorrect, as this crematorium was put into operation as early as in the beginning of May 1942.

iii. The Daily Period of Operation of the Ovens

At that time, stationary ovens were heated with coke. When such an oven is in operation for many hours, the grate is gradually covered with glowing cinders. For this reason, it is common practice to extinguish the oven in the evening and to let it cool off overnight. In the morning, the cinders are removed and the oven is rekindled. It was therefore not possible to operate a coke oven around the clock, as the experts assumed. On the other hand, it was theoretically possible to operate the oil-fired “field crematoria” around the clock. But according to the documents the staff of the Sachsenhausen crematoria never exeeded eight men, so it is highly dubious that it would have been feasible to operate these ovens continuously.

iv. The Insertion of Several Corpses into One Muffle

All ovens at Sachsenhausen, both mobile and stationary ones, were one-muffle ovens. The technical experts based their calculation of the daily capacity of these ovens on the ludicrous assumption that six (!) bodies had been simultaneously introduced into a muffle. Nevertheless, the cremation allegedly required only 60 minutes in the stationary ovens and only 30 minutes in the field crematoria! Apart from the fact that the muffles were much too small to allow for the simultaneous insertion of six bodies, this method would not have accelerated the process of cremation at all. Even today the incineration of an adult body in a muffle requires on an average at least 80 minutes.

Apparently the wildly unrealistic claims of the first draft (Shn-1) embarrassed even the ESC at Moscow. At any rate, the capacity of the crematoria was not even mentioned in the following drafts (Shn-2 and Shn-3). To make the cremation of the alleged number of victims technically feasible, the final version (Shn-6) resorted to a new trick, increasing the number of field crematoria at Sachsenhausen to eight.

As the reader will recall, the first draft wrongly claimed that the new crematorium had been put into operation in March 1943. This misstatement appears in the following versions as well:[36]

“In accordance with the plan of the aforementioned hangman Klein, a stationary crematorium was built in 1942 and put into operation in March 1943. Based on a project of camp commandant Sauer, and under his personal leadership, a gas chamber for the mass killing of people with the poisonous substance ’Zyklon A’ – a liquid product containing prussic acid – was installed in the building of the newly constructed crematorium.”

As a matter of fact, the epidemics of typhus (spotted fever) which had occurred in fall 1941 prompted the camp administration to order the construction of the new crematorium as early as winter 1941/42. This work only required four months; the crematorium was put into operation in the beginning of May 1942. As that winter had been particularly harsh, the experts in Moscow presumably thought that it would not have been possible to perform such a task within so short a time and therefore decided to “correct” the date.

5.3 The Shooting of the POWs

It is an undeniable fact that the large masses of Soviet prisoners of war who filled the German camps after the beginning of the Russian campaign were subject to scrutiny of their political background by the SD (Sicherheitsdienst, Security Service). Soviet functionaries, political commissars of the Red Army (Politruks) and other “carriers of the Soviet ideology“ were sorted out and sent to the nearest concentration camp to be shot.[37] Such executions occurred at Sachsenhausen as well.

What did the Special Commission at Sachsenhausen find out about the shooting of Soviet POWs? The so-called ”Häftlingsbericht” (Prisoners’ Report) produced in May and June 1945 under the authorship of Communist ex-prisoner Hellmut Bock put the number of victims at 16,000. Probably this figure was already mentioned in the missing first version of the ”Häftlingsbericht” (HB-1) which existed as early as 7 May 1945; an English translation of this document has survived (HB-2). In version HB-7, which was handed over to the Soviet Commission on 12 June 1945, the killing of the Russians is described in the following way:[38]

“Before the ogres slew, strangled or crushed the people, or killed them in other ways these murderous brutes had devised, they were fiendishly mistreated. The SS literally indulged in these orgies of murder. Rivers of brandy were consumed, and loudspeakers drowned out the cries of the victims with music. Nobody cared to verify the death of the victims before their cremation; many of them were shoved into the ovens while still alive.“

The Häftlingsbericht does not mention killings by shooting in the back of the neck through a slit in the wall, nor does it explain how the prisoners were able to ascertain the number of Russian POWs killed. On 29 June 1945, Lt. Colonel Sharitch, who had been in possession of the Häftlingsbericht for 17 days, finished his own final report of 28 pages. Inexplicably, only a single paragraph is dedicated to the shooting of the Soviet POWs, and no number of victims is given:[39]

”In the camp there were Soviet prisoners of war as well. They arrived at Sachsenhausen in large groups and for a special purpose – liquidation. This category of prisoners was not statistically registered. The Russian POWs were kept in special barracks behind barbed wire which isolated them from the other inmates. They did not even get the pitiful rations other prisoners were allotted.”

That was all the chief of the first Soviet “fact-finding commission” had to say about this subject. Now how did the ESC handle this report? In draft Shn-1[40], where the shooting of seven British sailors is described in great detail on three and a half pages (we will discuss this “British Sailor Case” later), the shooting of Soviet POWs is mentioned three times, but in an extremely cursory way and without any details. The number of victims is given as 14,000:

“Besides the systematic mass killings of political prisoners of various nationalities, the Hitlerites also annihilated Soviet prisoners of war and prisoners of war of the allied nations in the same camp.“ (p. 7)

”As the commission ascertained during its investigation, beside the annihilation of the English prisoners of war and the systematic killing of camp inmates a large group of Soviet prisoners of war was liquidated. The commission ascertained that in September/October 1941 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war were shot by the camp administration.” (p. 10)

The figure of 14,000 Russian POWs allegedly shot at Sachsenhausen is mentioned a third time in connection with the arrest of the former commandant of the camp, Loritz, by the British. According to the authors of the report, he was

”the direct organizer of the mass annihilation of camp inmates as well as the shooting of 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war in 1941.” (p. 11)

In Shn-2[41] and Shn-3[42] the reference to the shooting of the Soviet prisoners of war is even more laconic:

”Concurrently with the annihilation of the Englishmen in the Sachsenhausen camp, other prisoners of war were liquidated as well. The commission ascertained that in September/October 1941 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war were shot.”

The figure 14,000 is mentioned two more times in Shn-2 and Shn-3 (in both versions on pages 10 and 11), but details are again lacking. In the succeeding version (Shn-4) the 14,000 Soviet POWs are mentioned at the beginning of the chapter about the prisoners of war[43], but the reference to them is still cursory:

”In the course of the investigation it has been ascertained that in September/October 1941 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war were shot at the Sachsenhausen camp. In addition to the mass annihilation of Soviet prisoners of war in the camp, the Hitlerites also put to death captured soldiers and officers of the allied countries.”

Presumably it was Vyshinsky, who recognized the disproposition between the laconic mention of the (allegedly) 14,000 Soviet victims and the detailed description of the fate of 7 British POWs, and who demanded a modification of the text (as we learn from a letter of Bogoyavlenski[44] to Vyshinsky). Thus, Vyshinsky prompted the new draft Shn-4D, where the shooting of the British sailors is dealt with much more concisely (half a page instead of three and a half), while two new pages have been added under the heading ”The annihilation of the prisoners of war“[45]; half a page is now devoted to the Soviet POWs. The new chapter reads as follows:

The annihilation of the prisoners of war

”In August 1941 a first transport of 2,000 Soviet prisoners of war arrived at the Sachsenhausen camp. They were housed in various isolated barracks. Within 4-5 days, all prisoners of war were shot in the shooting ditch [“tir“ in Russian]. During their stay in the camp the Soviet prisoners of war were given neither food nor water. As witnesses stated, they were led to the place of execution in a state of utter exhaustion. As soon as the barracks had been emptied from the first group, a second transport consisting of 2,000 Soviet prisoners of war was brought to the camp and shot as well.

“Altogether, about 16,000 Soviet prisoners of war were deported to the Sachsenhausen camp by the Hitlerites in September/October 1941; up to 14,000 of them were shot. The Germans treated the remaining 2,000 Soviet prisoners of war with particular cruelty. They were used for the hardest work; in their barracks there were neither beds nor blankets, not even straw. The Soviet prisoners of war received only half of the meager rations other prisoners were allotted.“

The fragment Shn-5 contains a passage [46] which obviously constitutes a continuation of the preceding text and where the ”Ziereis confession” is mentioned for the first time:

”In 1941 the commandants of all German camps were summoned to Sachsenhausen in order to receive instructions as to the extermination of Soviet people, especially political officers [politrabotniki] of the Red Army. They were shown a new killing method: In a special room, the doomed were put against a wall to create the impression that it was intended to measure their height, whereupon they were shot in the back of the neck through a slit in the wall in which the measuring plate could be moved up and down.”

In Shn-5, the sentence “In a special room…” has been added in tiny handwriting, and – apparently as a confirmation – the meeting of camp commandants in Sachsenhausen is mentioned, according to the so-called “Ziereis confession”. In the final version, Shn-6, the sentence “In a special room…” appears in typewritten form and is followed by quotations from the Ziereis confession:

”During his interrogation, the former commandant of the Mauthausen concentration camp, Standartenfüher Ziereis, made the following statement:

’In 1941 all commandants were sent to Sachsenhausen in order to decide upon the speediest way to dispose of the Russian politruks and commissars. The Russian politruks and commissars were taken into a special building, and to the loud roaring of a loudspeaker each of them was led into the execution chamber. On the opposite side of the chamber there was a slit along which there was a movable [illegible handwritten word] device. Through this slit, the victim was shot in the back of the neck. This way of execution had been invented by Oberführer Loritz. Two SS-Oberscharführer were always standing next to the doomed; after the shot they threw the dead body on a board, and while others opened the door, they callously threw the body on a pile. Opposite the corpse building, eight mobile crematoria were constantly in operation. Every day 1,500 to 2,000 people were killed.’” (Shn-5, p. 7/2)

The final version Shn-6 contains both the aforementioned passages (“The annihilation of the prisoners of war“ from Shn-4D and the excerpt from the ”Ziereis confession“ from Shn-5). The annihilation of “the Soviet prisoners of war“ is now described on nearly two pages,[47] the wording being practically identical with the already quoted passages from Shn-4D and Shn-5. There is but one difference: Whereas ”up to 14,000” Russian POWs had been shot according to Shn-4,, Shn-6 contents itself with “more than 13,000” victims[48].

At first sight, the shortness and vagueness of the passages about the (alleged) shooting of 13,000 – 14,000 Soviet prisoners of war seems inexplicable, especially if one considers that as early as in May/June 1945 former inmates of the Sachsenhausen camp had described the so-called ”Russenaktion” in the most horrific way. We have already mentioned the Häftlingsbericht[49] which was submitted to the special commission on 12 June 1945. Had the ESC in Moscow perhaps not read these reports, or did they doubt the veracity of such ”eyewitness testimony”? In our opinion, there is a simple explanation for this seeming paradox. From Stalin’s point of view, the hundreds of thousands of Soviet soldiers who, instead of doing their duty and fighting to the last cartridge, had surrendered to the Germans in the summer and autumn of 1945 were nothing but despicable traitors. After the war the ”liberated“ soldiers of the Red Army were subject to the most severe scrutiny; many of them were deported to the camps of the Gulag[50]. As a matter of fact, Soviet post-war propaganda shuns the subject and does not express the slightest sympathy for their captured countrymen.

The account of the ”annihilation of the Soviet prisoners of war“ conveyed by the final draft Shn-6 contains several highly questionable claims:

i. The Meeting of the Commandants

The alleged meeting of the camp commandants at Sachsenhausen mentioned by Ziereis in his ”confession“ would have taken place in July (the Russian campaign started on 22 June 1941) or in August 1941 (according to the Soviets, the ”Russenaktion“ began in late August). Some of the commandants did not survive the war, and those who did were in most cases sentenced to death and executed. There is no evidence that any of them has confirmed the reality of the meeting at Sachsenhausen.

ii. The Beginning of the Shootings

The first transport with 2,000 Soviet POWs reached Sachsenhausen towards the end of August 1941. Starting with this transport, ”about 16,000 Soviet prisoners of war“ were taken to the camp, more than 13,000 of whom were allegedly shot, so only about 2,000 were still alive after the end of the ”action“. Contrary to the Soviet version of the events, circumstantial evidence points to the fact that the first Russian POWs reached Sachsenhausen as late as in the middle of October 1941. Up to the present day it is not certain when the shooting of Russian POWs really began.

iii. The Alleged Daily Killing Rate

According to the report, the 2,000 POWs who had arrived with the first transport were all shot within 4-5 days (which means that the number of daily executions must have amounted to 400-500). The end of the respective passage reads as follows: ”Every day 1,500 to 2,000 persons were killed.“[51] These figures are utterly ludicrous because the two, three or four existing field crematoria and the aproximately eight crematorium workers could not even remotely have coped with such a number of corpses.

iv. The Disposal of the Bodies

If we are to believe the commission, two SS-Oberscharführer (sergeants) had to remove the corpses. How on earth could these two men have dragged or carried 1,500 – 2,000 bodies to the ovens every day? According to a later testimony of Paul Sakowski the corpses of the victims were taken to the ovens by several prisoners; the figure of 1,500 – 2,000 victims per day is not mentioned by this witness.

One would have expected the ESC to present the results of its own special commission in its final report. After all, this commission had carried out its investigation at the Sachsenhausen camp during several weeks, and at that time there were still plenty of former inmates who could be questioned. Significantly, the commission had nothing concrete to say about the alleged mass shootings of Soviet POWs. The former detainee and crematorium worker Paul Sakowski, who had been forced to participate in the ”Russenaktion“ and later became a key witness of these events, had been in NKVD custody since the beginning of June 1945 where he was repeatedly interrogated, but he only submitted his detailed written testimony in early 1946. At any rate, the ESC preferred the ”confession“ of the deceased Franz Ziereis to the testimony of Paul Sakowski who was still very much alive. After all, a dead witness cannot speak any more and a dead ”perpetrator” cannot retract his confessions.

5.4 The Gas Chamber

According to the Technical Report, a homicidal gas chamber was installed in the building of the new crematorium. The Soviet experts furnished a detailed description of the ”apparatus for the evaporation of prussic acid“ said to have been installed on the back wall of the neighboring room (the so-called garage) but hushed up the fact that this wall was bare at the time of their arrival and that parts of the apparatus were (allegedly) found in a well. The various drafts of the ESC contain a certain amount of information about the technical aspects of the gas chamber.

5.4.1 Capacity of the Gas Chamber

If we follow the Technical Report, 60 persons could be simultaneously killed in the gas chamber[52]. Sharitch´s final report[53] was finished on 29 June 1945 and Shn-1 (undated) presumably at the beginning of July. Both documents mention the alleged killing capacity of this chamber during the whole time of its existence in the same words:

”In the gas chamber of the crematorium, 285,000 persons could be annihilated during the period of its existence from April 1943 until April 1945.”

If 285,000 persons could be gassed in two years (731 days), this would have meant (285,000 ÷ 731 =) 390 gas chamber murders per day. If the capacity of the gas chamber amounted to 60 victims, 6-7 daily gassing operations would have been needed, even on Sundays and holidays. To give the devil his due, Semyonov, the author of Shn-1, does not claim that this theoretical capacity was ever reached in practice, and in the subsequent drafts the subject is quietly dropped.

5.4.2 When Was the Gas Chamber Completed?

As we have pointed out in subchapter 5.2, the ESC erroneously assumed that the new crematorium had been completed as late as in March 1943 (as a matter of fact, it was already finished in the beginning of May 1942). From the point of view of the commission, the gas chamber could evidently not have been used before the construction of the crematorium was completed. In the light of these facts, it is hardly surprising that the former commandant of Sachsenhausen, Anton Kaindl, stated during his trial (October 1947) that he had ordered a gas chamber to be installed in March 1943, thus confirming the Soviet version of the events. It is a well-known fact that at Stalinist show trials the defendants regularly confessed everything the court desired to hear.

5.4.3 The Operation of the Gas Chamber

The Technical Report contains a relatively detailed description of the operation of the gas chamber.[54] The poisonous liquid which evaporated in the apparatus is sometimes called ”prussic acid”, sometimes ”Zyklon A“. However, it is highly improbable that such exceedingly dangerous toxic liquids were actually used in fragile glass bottles, and the method described completely deviates from the state of the art of dealing with prussic acid which was usual at the time in Germany. Indeed, prussic acid was used on a large scale to eradicate vermin, but only in the form of the pesticide Zyklon B, where the acid was absorbed in gypsum pellets that slowly outgassed after the opening of the can.

To cut a long story short, the report of the Soviet technical experts raises plenty of questions which remain unanswered up to the present day. Of course this report was not destined for the public, and the ESC did not have to fear irksome questions from skeptical readers.

5.5 The Shooting Facilities

As to the shooting facilities of Sachsenhausen, we have to differentiate between three (fictive or real) installations, which must not be confused with each other:

5.5.1 The Shooting Ditch (Dug in Early 1941)

This ditch, which still exists today, was called Schiessstand (shooting range) in the jargon of the prisoners; the word тир used by the Soviet commission being simply a translation of this word. In all likelihood it was dug in early 1941 as a regular place of execution by shooting (picture 7). The executions were carried out by firing-squad, not by shooting in the neck. There is only one proven case of a mass execution in this ditch: On 2 May 1942, 71 Dutchmen (most of them former officers of the Dutch army who had formed an underground movement) were executed by firing-squad.

Paul Sakowski,[55] who had been infected with typhus and spent five months in his cell in the Camp Prison, became an earwitness to the arrival of the Dutchmen and their last night in the prison, when they sang their national songs. The next morning Sakowski (who had recovered from typhus and had to report for work again for the first time), witnessed, standing outside the new crematorium, the execution of the Dutch officers. They were in small groups led down into the ditch where their sentence was read by a German officer. They were allowed to smoke a last cigarette and to choose whether they wished to be blindfolded or not. The execution lasted several hours.

Another mass shooting occurred on 9 November 1940 when 33 Poles were executed. The execution is mentioned in one of the earliest inmate reports[56] and in almost all early inmate testimonies (Fliege, Šlaža [Shlasha], Weiss-Ruethel, Wunderlich). Additionally, the delinquents had been registered by the Register Office (Standesamt) of Oranienburg, which was discovered by an inquiry of the Nationale Mahn- und Gedenkstätte Sachsenhausen[57]. The shooting ditch did not yet exist at that time, but at the same place was apparently a small sand-pit, which had to fulfill the same purpose [58]. The reason for the execution of the 33 Poles was presumably atrocities committed against the German minority in Poland on 3 September 1939 (“Bromberg Bloody Sunday”).

Yet another mass execution by shooting is alleged to have taken place in the night from 1 to 2 February 1945, but no details are known; the number of victims reportedly amounted to between 130 and 189. The only point the witnesses agree on is that the doomed were shot “on the area of the crematorium“, which means that the execution could have taken place either within the crematorium building or in the shooting ditch. The events of that February night are reported in several early testimonies, e.g. in the so-called Häftlingsbericht (Prisoners´ Report)[59]. All these testimonies are contradictory and vague, due to the fact that the inmates could only hear, but not see, what actually happened.

Source: Internet (ca. 2002).

5.5.2 The “Shooting Hut” with a Neck-Shooting Facility (“Russenaktion”, Fall 1941)

According to the testimonies of former prisoners (Sakowski, Zwaart, Weiss-Ruethel etc.), the liquidation of Soviet POWs (”Russenaktion“) occurred in a hut in the North Yard. The exact position of that hut is unknown, but it was situated – according to Sakowski – very close to the place where the new crematorium would be built in Spring 1942.

Prior to the arrival of the first transports with Russian POWs, the SS had allegedly installed a neck-shooting facility in the hut and set up four field crematoria in front of it. The shooting hut is said to have been demolished in connection with the construction of the new crematorium (about January – May 1942). There is no photo and no blueprint of this hut. On the other hand, there was a big hut (or storage shed) only 30 meters from the new crematorium, which had been used as a store for the property of deceased concentration camp inmates from Eastern camps. The shed still existed intact at the end of the war and is well documented by Soviet photos (May/June 1945). We cannot rule out that perhaps this shed had been used as the “shooting hut” for Soviet POWs, since the shooting facilities were needed – after all we read – only some weeks in fall 1941 and for much fewer victims than the purported 14,000. The murder of the Soviet POWs (“Russenaktion”) raises many questions, that still lack credible answers. The big shed was demolished years after the war; only its outlines are still marked in the soil.

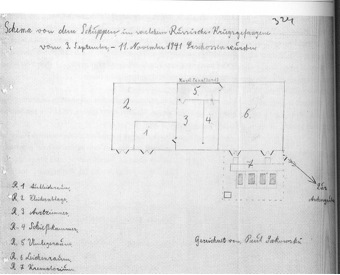

Source: Paul Sakowski[60], published in G. Morsch , p. 54.

5.5.3 The Neck-Shooting Facility (Shooting Rooms) in the New Crematorium

The new crematorium was built as a consequence of the epidemic of typhus which had broken out in mid-November 1941 and had led to putting the camp under quarantine. Reportedly a neck-shooting facility was installed in the new crematorium from the very beginning. The Soviet experts from the Technical Commission who inspected the (still intact) crematorium in May/June 1945 described the ”shooting rooms“ (комнаты для расстрела) as if they had seen them in operation with their own eyes [61]. According to the experts, the unsuspecting victims had to stand under a measuring rod. Like the adjacent wall, this rod had a vertical slit through which an executioner standing in the adjacent room killed the victim by a shot in the neck. This slit in the wall (“embrasure,” Russ. ambrasura) is quoted in the Technical Report as key evidence for the murderous purpose of these rooms.

But is there any convincing evidence that these ”shooting rooms“ actually existed? The technical experts Blokhin, Telyaner and Grigoryev insinuate having seen them, but do not explicitly say so. Since it is routinely claimed that the SS destroyed the evidence of their atrocities before retreating, it would be very odd indeed if they had acted differently in this case. Shortly after the end of the war, former inmates (e.g. Weiss-Rüthel, Zwaart) of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp furnished a fantastic description of the “neck-shooting facility“, but they did not explain where they had got their knowledge from, access to the crematorium being strictly forbidden to unauthorized persons. Probably these testimonies did not yet exist in May/June 1945, otherwise the Soviet experts would have quoted them. It is true that a blueprint of the crematorium shows a complex of three or four tiny rooms [62] allegedly identical with the ”shooting rooms”. The catch is that this is not the original German blueprint (said to be lost); it is a Soviet blueprint allegedly based on a new measuring of the whole building, which proves precisely nothing.

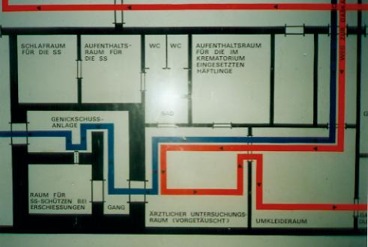

In compliance with the Soviet version, the authorities of the GDR drew a blueprint showing these ”shooting rooms“. Official historiography still holds to this version (illustration 9).

Source: Exhibit in front of the crematory (April 2000).

Now what has the Sachsenhausen report of the ESC to say about ”shooting rooms?“ The first draft (Shn-1) does not mention any shooting rooms or any neck-shooting facility in the crematorium but claims instead that executions took place in the shooting ditch[63]:

”The mass execution of camp inmates and new transports by the Germans was carried out by hanging, shooting and gassing. As a rule, the shootings occurred in a special ditch in the area of the crematorium behind the outer wall of the camp. In 1941 the Hitlerites began their mass shootings of prisoners on the area chosen for the construction of the crematorium.”

This passage reappears in drafts Shn-2 and Shn-3; in Shn-4 and Shn-6 it has been slightly modified[64]:

”The mass annihilation was carried out by hanging, shooting and gassing. As a rule, the shootings occurred in a special ditch in the area of the camp crematorium.“

Not until Shn-5 and Shn-6 does the execution method ”shooting in the neck” appear in connection with the killing of Soviet POWs. In accordance with the Ziereis confession and inmate testimonies, these drafts claim that the killings were carried out in the ”shooting hut“ mentioned under b) which was allegedly demolished in 1942. (We remember that the new crematorium, whether it had shooting rooms or not, did not yet exist at the time of the “Russenaktion”). Hence the amazing fact that the shooting rooms (neck-shooting facility) described by the Soviet experts in their technical report and shown on the Soviet blueprint are not mentioned in any of the different drafts of the ESC report about Sachsenhausen!

According to a certain number of witnesses, people were regularly taken to the “area of the crematorium“ to be shot there (especially after February 1945). Even if the ”neck-shooting facility“ was a creation of propaganda, it would have been possible to carry out executions in the ”shooting ditch“. On the other hand, this ditch was very close to the nearest barracks (less than 100 meters as the crow flies). Although the prisoners in the camp would not have been able to see what was going on in the ditch (after all, the dwelling barracks and the ditch were separated by the camp wall), they would certainly have heard the shots, and the shooting would have stuck in their minds. In general, inmate testimonies about groups of people being led to the ”area of the crematorium“ in order to be killed there, are unsubstantiated claims – vague and unconvincing. They are insufficient to prove that the alleged mass murder by shooting really occurred.

5.6 The “British Sailors Case”

The seven young members of the Royal Navy whose fate is discussed here had participated in a commando raid (“Operation Checkmate”). Led by Temporary Lieutenant John Godwin, they undertook acts of sabotage, e.g. to sink German vessels at the Norwegian coast by means of limpet mines. They succeeded in sinking one minesweeper. On 15 April 1943, two weeks after being put ashore by a British torpedo boat, they were captured by the Germans[65]. For all of them this was the beginning of a tragedy (illustration 10).

Photograph: Kenneth Macksey, Godwin’s Saga, 1987.

From the German point of view commando raids were a violation of the rules of warfare. Therefore, Hitler had issued his so-called Commando Order (Kommandobefehl) of 18 Oct. 1942 which stipulated that all captured commandos, no matter if they were in uniform or not, were to be executed immediately after interrogation. From the British point of view the members of the commando should have been treated as prisoners of war, since they were captured in uniforms. The Wehrmacht apparently tried to circumvent this order, but the seven sailors were denied regular POW status, they were handed over to the Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst, SD) and were sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp rather than to a regular POW camp (Sept. 1943).

After a few weeks as ”normal“ concentration camp inmates, they were for some unknown reason assigned to the punishment battalion and forced to march on the boot-testing track six days a week. Presumably, the German side tried to exchange them for German POWs, but the offer was rejected by the British government. This was probably the reason that, only a few weeks before the end of the war, six of the sailors were finally shot, while the seventh died of typhus.

The reports and testimonies differ significantly in the details. The Soviet investigator Lt. Colonel Sharitch writes in his Final Report[66] that five men were shot in the night of 1/2 February, “together with a group of other prisoners containing altogether 189 men who were brought to the area of the crematorium and shot there.” The details of what transpired in that February night are unknown. Alfred Roe (who lay with typhus in the camp hospital) and Keith Mayor survived at first. On 26 February Roe was transferred to Bergen-Belsen, but retransferred to Sachsenhausen on 9 April 1945. Sharitch quotes here the official German Veränderungsmeldung (daily roll-call report) from 11 April 1945, which said that Roe had been shot the day before ”while trying to escape“. Keith Mayor was transferred on 20 February to Buchenwald, and nothing was known about his further fate. Generally, Sharitch relied in his narration on several inmate witnesses (Hans Apel, Gulsmit, Otto Heiler, Paul Sakowski), and there is no doubt that – in this case – the Soviet side tried to find out the truth. The question is whether the witnesses knew or always told the truth. According to later British sources, [67] Mayor and Roe had been transferred to Belsen concentration camp, where Mayor was executed on 7 April 1945 and Roe died of typhus.

In Sharitch’s final report and in the first ESC drafts (Shn-1 to Shn-4c) much space was devoted to the sad fate of the 7 British sailors, undoubtedly because the British had urged their Soviet allies to investigate, and we cannot see any signs of manipulation in this case. Remarkable is another fact: In draft Shn-4d the whole story has been expunged by hand except the last one sentence. And in Shn-6 (the final version) only that sentence has remained:

”Based on eyewitness testimony and documents it was ascertained that during various periods some groups of captured English soldiers and officers were interned and annihilated at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.“

5.7 Sachsenhausen Statistics

A first analysis of the prisoner statistics of Sachsenhausen was conducted by a team of former inmates (Walter Engemann, Gustav Schöning and Hellmut Bock), who performed this task in May/June 1945 at the behest of the Soviet special commission. The Engemann team examined the daily roll call reports (which were almost completely available) and other authentic SS files, and documented their results in a report, which we will call here the “Engemann Protocol”[68]. More recently the Sachsenhausen statistics were again analyzed by C. Mattogno[69] and K. Schwensen [70].

5.7.1 The number of prisoners ever registered in the camp

The total number of prisoners who were registered in the camp during the whole period of its existence (der Durchgang) is given in all reports as slightly over 100,000[71]:

”During the period of existence of the camp until the day of its evacuation, citizens of 34 nations were imprisoned there. […] During the same time 100,000 prisoners sentenced to limited and unlimited prison terms by the Hitlerites passed through the camp. Both the number of inmates and their national composition greatly varied. In 1945, 58,000 persons were confined in the camp.“

The total figure of 100,000 prisoners is too low. Former detainees put the number at 137,000, and it surely did not exceed 150,000. Later, when the Soviets claimed that 100,000 people had perished at Sachsenhausen, they simply doubled the total number of prisoners deported to the camp, now mentioning a figure of 200,000.

5.7.2 The headcount

The headcount (die Lagerstärke) is the total number of prisoners at the same time. According to the ESC, the highest headcount amounted to 58,000. This figure was correct, as the headcount reached its peak in January 1945, when 58,147 (male) prisoners were confined.[72] In a letter to Molotov, Chvernik erroneously related the 58,000 figure to March 1945[73], but in March the evacuation of the camp was in full swing, and the number of inmates had fallen to 34,873. These figures refer to the main camp plus all satellite camps and outstations, but they do not include the female prisoners.

5.7.3 The death toll

In his final report (which was already in possession of the ESC when they started with their own report), Lt. Colonel Sharitch stated that 19,900 prisoners had died at Sachsenhausen:

”An analysis of the statistical data, only a part of which was at the disposal of the fact-finding commission, shows that in the period from 1940 to 1945 19,900 persons perished at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.“

The figure of 19,900 dead was based on the authentic ”Veränderungsmeldungen“ (daily roll call reports). It does not take into consideration the 273 prisoners deceased in 1936-1938, nor the 819 deaths which had occurred in 1939 (the total death toll from 1936-1945 thus being 20,992). The ESC accepted the figure of 19,900 victims but arbitrarily shortened the period to which it referred. The following sentence appears unchanged in all drafts:[74]

”Based on documents found at the camp it was ascertained that in the period from 1942 to 1945 19,900 people died at the Sachsenhausen camp from various kinds of diseases alone.“

This sentence contains two manipulations:

a) In the 64 months from January 1940 until April 1945 19,900 prisoners died at the camp. However, the ESC claimed that this death toll was reached ”in the period from 1942 to 1945“ (to-wit, within 40 months), thus insinuating that the total number of victims was considerably higher, as the reader would naturally assume that numerous detainees had perished in the preceding years as well.

b) The formulation ”from various kinds of diseases alone“ insinuates that these 19,900 deaths were only a part of the total toll. As a matter of fact, the Soviet operatives later conjured up all kinds of other categories of victims without adducing any evidence to corroborate this claim.[75]

A thorough analysis of the existing documents has shown that from 1936 to 1945 about 22,000 male prisoners died at Sachsenhausen plus its satellite camps and outstations. The number does not include the Soviet prisoners who were shot or perished in the camp, the female detainees in the satellite camps and the casualties of the evacuation march. Much additional research is necessary here.

It goes without saying that for the Soviet propaganda the real death toll of the camp was not terrible enough. As early as in 1945, it was brazenly claimed that no fewer than 100,000 prisoners had perished at Sachsenhausen. This propagandistic assertion is confirmed by a report of the former Lt. Colonel of the German parachute troops, Gerhart Schirmer, who was interned in the Soviet special camp No. 7 (Sachsenhausen) from September 1945 until January 1950. By order of the Soviet operatives, Schirmer and another seven German prisoners were forced to build a ”gas chamber“ and a ”neck-shooting facility“ which were later shown to Soviet groups of visitors as evidence for German atrocities. The detainee Fritz Dörbeck, who spoke Russian, was compelled to ”explain“ everything to the visitors and to state that ”the Nazis gassed about 100,000 people in this room and shot hundreds in the neck-shooting facility.”[76]