Auschwitz and the Exile Government of Poland According to the “Polish Fortnightly Review” 1940-1945

1. Motive and Genesis

For some time I have been interested in knowing how the Polish Government-in-Exile reacted to the enormous slaughter of Jews that supposedly took place in the concentration camp of Auschwitz.

Whatever may have occurred in Auschwitz, it was the concern of the Polish exile government, for Auschwitz was on the territory of the Polish Republic until September of 1939, and the Polish government that was installed in London beginning in June of 1940, recognizing none of the territorial annexations carried out by Germany, claimed jurisdiction over all of prewar Poland.

Accordingly, I have taken as my point of departure for this study the assumption that if a great slaughter of Jews had taken place in Auschwitz, the Polish Government-in-Exile would have known of it and in consequence manifested a reaction of some kind.

2. Purpose and Limits

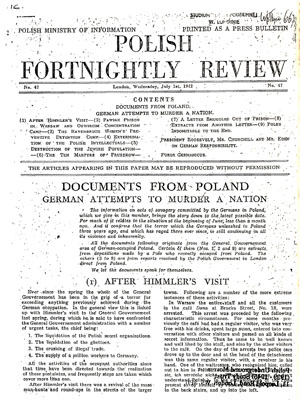

The goal of this article is to determine whatin fact was published about Auschwitz by the Polish Fortnightly Review, the official organ of the Ministry of the Interior of the Polish government in London; and it is therefore limited to a study, based solely on those issues of the Polish Fortnightly Review published from 1940 to 1945, of what was known by the Polish Government-in-Exile with regard to the Auschwitz camp. Other questions, such as analysis of the documents relating to Auschwitz that were sent to London by the Polish resistance, or the study of the references to that camp in the Polish underground press, have not been touched on in this investigation.

The selection of the “Polish Fortnightly Review” was motivated principally by three things:

- the fact that it was an official organ of the Polish Government-in-Exile (see document I);

- the fact, as pointed out by the Israeli professor David Engel, that it was one of “the principal vehicles for disseminating Polish propaganda in the English language” and “a primary vehicle through which the government released information to the Western press”;[1] and

- my incomprehension of the Polish sources, due to my still deficient understanding of that language; whereas the Polish Fortnightly Review, published in English, was accessible to me.

3. Bibliography

- Bor-Komorowski, Tadeusz, The Secret Army, London: Victor Gollancz, 1950, 407 pp.

- Buszko, Jozef, “Auschwitz, ” in Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, New York: Macmillan, 1990, pp. 114-115.

- Czech, Danuta, Kalendarium der Ereignisse im Konzentrationslager Auschwitz-Birkenau 1939-1945, Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1989, 1059 pp.

- Duraczynski, Eugeniusz, “Armia Krajowa, ” in Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, New York: Macmillan, 1990, pp. 88-89.

- Duraczynski, Eugeniusz, “Delegatura, ” in Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, New York: Macmillan, 1990, pp. 356-357.

- Duraczynski, Eugeniusz, “Polish Government-in-Exile, “in Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, New York: Macmillan, 1990, pp. 1177-1178.

- Engel, David, In the Shadow of Auschwitz: The Polish Government-in-Exile and the Jews, 1939-1942, Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1987, xii [/3] 338 pp.

- Garlinski, Jozef, Poland, SOE and the Allies, London: Allen and Unwin, 1969, 248 pp.

- Garlinski, Jozef, Fighting Auschwitz: The Resistance Movement in the Concentration Camp, London: Friedmann, 1975, 327 pp.

- Garcia Villadas S.I., Zacarias, Metodologí y crítica históricas, Barcelona: Sucesores de Juan Gili, 1921.

- Höss, Rudolf, Kommandant in Auschwitz: Autobiographische Aufzeichnungen, Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 1989, 189 pp.

- Jarosz, Barbara, “Le mouvement de la résistance à l'intérieur et à l'extérieur du camp,” in Auschwitz camp hitlérien d'extermination, Warsaw: Interpress, 1986, pp. 141-165.

- Karski, Jan, Story of a Secret State, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1945, 319 pp.

- Klarsfeld, Serge, Le Mémorial de la déportation des juifs de France, Paris: Beate et Serge Klarsfeld, 1978, pages not numbered.

- Klarsfeld, Serge and Steinberg, Maxime, Mémorialde la déportation des juifs de Belgique, Brussels-New York, no date, pages not numbered.

- Langbein, Hermann, Hommes et femmes à Auschwitz, Fayard (place of publication not given, 1975, 527 pp.

- Langlois, Charles-V. and Seignobos, Charles, Introducción a los estudios históricos, Buenos Aires: La Pélyade, 1972, 237 pp.

- Laqueur, Walter: The Terrible Secret. Suppression of the Truth about Hitler's “Final Solution”, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980, 262 pp.

- Mattogno, Carlo, The First Gassing at Auschwitz: Genesis of a Myth, in The Journal of Historical Review, Torrance, 1989, pp. 193-222.

- Nowak, Jan, Courier from Warsaw, London, Collins and Harvill, 1982, 477 pp.

4. Sources

Research was conducted at the end of April and beginning of May of 1991 using the collection of the Polish Fortnightly Review preserved in the Polish Library of the Polish Social and Cultural Association of London. The initial issue of the review was published on 15 July 1940 and the final one (number 119) on the 1 July 1945. I read through the collection issue by issue and page by page and noted that numbers 97 (1 August 1944), 101 to 106 (1 October to 15 December of 1944), and 116 to 119 (15 May to 1 July of 1945) were missing and so were not available for examination.

As for the documents cited in section 4.2 and in appendix 2, they come from the archives of the Polish Underground Movement (1939-1945) Study Trust (Studium Polski Podziemnej [SPP]) of London.

5. Method

This study was developed in the following manner:

- I have endeavored to find out how the Polish government was able to know what was going on inside Auschwitz and specifically what channels of communication existed between the camp and London; and

- I have made a special point of information about Auschwitz published in the Polish Fortnightly Review relating to the supposed extermination of Jews there, and in particular what it published in that regard, what it did not publish, and why.

It should be noted that, when referring to Auschwitz, the Polish Fortnightly Review always uses the Polish designation of Oswiecim.

Lastly, the abbreviations and acronyms used in this article are as follows:

- ACPW: Akcja Cywilna Pomocy Wiezniom (Civil Action in Aid of the Prisoners)

- AK: Armia Krajowa (Home Army)

- BBC: British Broadcasting Corporation

- BIP: Biuro Informacji i Propagandy (Office of Information and Propaganda)

- PGE: Polish Government-in-Exile

- PFR: Polish Fortnightly Review

- PWCK: Pomoc Wiezniom Obozow Koncentracyjnych (Aid for Concentration Camp Prisoners)

- RAF: Royal Air Force

- SOE: Special Operations Executive

- SS: Schutzstaffel (Protection Detachment)

- ZWZ: Zwiazek Walki Zbrojnej (Union for Armed Conflict)

1. POLISH INSTITUTIONS DURING THE WAR

1.1 The Polish Government-in-Exile

After the occupation of Poland by the Germans and Soviets in September of 1939, a Polish government was formed that was determined to continue the struggle for independence, sovereignty, liberty and the territorial integrity of the Polish Republic. This new government believed that these objectives could be achieved only after the crushing of the Third Reich and by means of an alliance with the Western powers.

The cabinet was sworn in on 1 October 1939 before the new president, Wladyslaw Raczkiewicz. General Wladyslaw Sikorski was the prime minister.

For obvious reasons the cabinet met in exile. First it set up in Paris. Later, in the face of the German advance, it moved to Angers, in the western part of France. Finally, after the sudden collapse of France in June of 1940, it fled to London.

The PGE was recognized by all the Allied nations, including (from July of 1941 to April of 1943) the Soviet Union.[2]

The PGE maintained contact with occupied Poland, though its contacts of course were carried out clandestinely. Instructions, orders, directives and in general all kinds of information destined for Poland were almost always transmitted by means of the Polish section of the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The SOE, whose political chief was the British Minister of Economic Warfare, was an organization charged with carrying the war to the territories occupied by Germany. The Polish section of the SOE cooperated closely with the Polish General Headquarters in London; it sent radio messages and frequently dropped agents by parachute. Starting in 1942, the dropping of agents became routine; and from 1944 on, even airplane landings were made on improvised airstrips.[3]

1.2 The Delegatura

The Delegatura, which operated from 1940 into 1945, embodied the PGE's clandestine representation inside Poland. It was headed by a delegate ( Delegat ) and three substitutes. The delegate was assisted by a committee made up of members of the political parties on which the PGE was based.

The Delegatura functioned as a shadow government and had numerous sections, corresponding to the ministries of a regular administration. The organization extended to the provinces, districts and townships and so was a broad underground network that covered all of Poland. In practice, the Delegatura directed a true alternative government, a secret state with its own educational system, its courts, its welfare organizations, its intelligence service and its own armed forces.[4]

1.3 The Armia Krajowa

Paralleling the Polish armed forces which fought the Germans openly under British command and which were made up of Poles who had managed to escape from Poland, there existed an actual secret army, the Armia Krajowa (Internal Army), which operated secretly within the bordersof prewar Poland.

The AK was formed in February of 1942 on the basis of a prior clandestine military organization, the Zwiazek Walki Zbrojnej (Alliance for Armed Conflict). General Stefan Rowecki was its first commander. After the latter's detention by the Germans in 1943, General Bor-Komorowski was appointed to the post.

The AK was organized as a real army, with a general staff, professional officers, an intelligence service, a service corps, etc., and it was divided territorially in accordance with the administrative division of the prewar districts. Thus, for example, in the organization chart of the AK, the Auschwitz zone was part of the district of Silesia.

In terms of manpower, it is reckoned that in the first half of 1944 the AK numbered between 250, 000 and 350, 000 men, including more than 10, 000 officers.[5]

2. CHANNELS OF COMMUNICATION BETWEEN AUSCHWITZ AND LONDON

2.0 Preliminary Considerations

Our immediate concern will be to find out whether the PGE in London could know what was going on in Auschwitz and, specifically, whether it could have had knowledge of a gigantic slaughter of Jews that had supposedly taken place in the camp.

In sum, this is a matter of determining the sources of information available to the PGE. For that it will be necessary first to establish whether in fact there were clandestine resistance organizations in the concentration camp, then whether or not they were able to obtain trustworthy information and get it out of the camp, and lastly whether they could get this information to London.

2.1 The Clandestine Resistance and Intelligence Organizations inside the Camp

A resistance organization existed in the concentration camp as early as October of 1940. It was founded by a Polish officer, Witold Pilecki, who had been arrested and sent to Auschwitz in September of 1940. About the same time, a resistance group of the Polish socialist party was also established; and later, in 1941, a rightist organization was formed under the direction of Jan Mosdorf. Finally, in May of 1943, an international resistance organization was created, the Kampfgruppe Auschwitz (Auschwitz Combat Group), which took in members of various nationalities, principally of socialist and communist ideology.[6]

The various organizations established contact with one another more or less frequently, depending upon their national or ideological affinities.

Among the objectives of the resistance was that of “gathering evidence relative to crimes committed by the SS and transmitting it abroad.”[7]

As the concentration camp installations were expanded, the clandestine organizations grew proportionately. In Birkenau, an underground organization created by Colonel Jan Karcz was in existence by April of 1942. Karcz recruited a large number of members and created his own “apparatus, ” the only way to direct clandestine operations in such a large camp. Some of Karcz's men were placed in blocks of Jews expressly to try to help alleviate their suffering. Contact between the Birkenau organization and that of the main Auschwitz camp was maintained on an almost daily basis by means of a liaison. Gathering information was one of the principal tasks of the Karcz group.[8]

In about the middle of 1943, a secret organization was established in the Birkenau women's camp. One of its activities was the passing of information about life in the camp. Contacts between this women's group and the main camp were effected by means of a “mailbox” where secret messages were delivered and received.[9]

The growth of the resistance organizations' membership, from the time of the camp's opening, was spectacular. By 1942, Pilecki's organization alone had around 1,000 members, divided between Auschwitz and Birkenau. Pilecki states that in just one month, March 1942, he personally recruited more than 100 persons for his group alone. The nationalist and socialist organizations grew as well.[10] In the same year, Colonel Kazimierz Rawicz, leader of a clandestine organization of prisoners, prepared a plan for a massive revolt in the camp and surrounding area, a plan which he sent to the commander of the AK so that he could set the date for initiating the action.[11]

The resistance groups were so strong by 1942 and 1943 that they had managed to introduce their tentacles into the nerve centers of camp life. Their members controlled the hospital, the work assignment office, and exercised vital functions in the central office, the kitchen, the construction office, the food and clothing warehouses, many of the prisoner work detachments (Kommandos) and even the political department.[12]

The clandestine groups had even gained the complicity of some members of the SS, mainly Volksdeutschen,[13] who had promised them assistance and access to the munitions depot in the event of an uprising.[14]

In view of the foregoing, several conclusions must be drawn:

- that resistance organizations were already functioning by the end of 1940, scarcely more than a few months after the opening of the camp;

- that these organizations had a considerable number of members and had spread throughout all sectors of the extensive prison complex of Auschwitz-Birkenau by at least the year 1942; and

- that therefore, if there had been any systematic killing of Jews from 1942 on, the resistance organizations would have been in a position to know of it in detail.

2.2 The Resistance Organizations outside the Camp

Clandestine organizations also existed at anearly date in the area surrounding the concentration camp. In 1940 the ZWZ created the Oswiecim (Auschwitz) district, which formed part of the Bielsko “Inspectorate.” In 1942, the ZWZ took the name of Armia Krajowa.[15]

The resistance was very active in the Oswiecim district. The Polish Fortnightly Review gives evidence of this. It mentions, for example, that several freight trains were derailed on the outskirts of Oswiecim in July of 1943.[16]

It was pointed out in the foregoing section that there were plans for an uprising in Auschwitz. These plans merited the attention of the general staff of the AK, which sent one of its men to the area to get a more precise idea of the situation. The officer in question was one Stefan Jasienski, who had arrived from England by parachute. Jasienski, a specialist in intelligence work, was sent from Warsaw to the immediate area of Auschwitz at the end of July of 1944. Given the importance of his mission, he was provided with all necessary contacts in the area and especially with means for secretly effecting liaison with the “military council” of the camp.[17]

Clandestine organizations were also created for the sole purpose of giving assistance to the prisoners of Auschwitz and maintaining contact with them. Thus, by the second half of 1940, a group called Akcja Cywilna Pomocy Wiezniom (ACPW – Civilian Action for Prisoner Assistance) was formed, the principal task of which was the collection of food, medicine and clothing, and then getting them into the camp through their camp contacts. These same contacts also served for passing messages back and forth. In May of 1943 a committee was formed in Cracow named Pomoc Wiezniom Obozow Koncentracyjnych (PWOK – Aid for Prisoners of Concentration Camps), the aims of which were similar to those of ACPW. The PWOK, despite the plural in its name, worked exclusively in behalf of the prisoners of Auschwitz.[18]

Having established the existence of clandestine organizations both within and outside the camp, we now have only to see how contact was established between them.

2.3 Contacts between the Camp and the Outside

Contacts between the interior of the camp andthe outside were facilitated by the location of Auschwitz. As the author Walter Laqueur acknowledges, Auschwitz did not lie in a wilderness, but in a densely industrialized and very populous area, near such important cities as Beuthen (Bytom), Gleiwitz (Gliwice), Hindenburg (Zabrze) and Kattowitz (Katowice). Auschwitz, moreover, was a virtual “archipelago, ” with about 40 administratively dependent subcamps.[18]

Besides the peculiar situation of Auschwitz, contacts were facilitated by the fact that many of the prisoners worked outside the camp together with members of the civilian population, and also because many civilian laborers worked within the camp.[19]

Specifically, with regard to the civilian workers, it suffices to say that there were hundreds of them and that there were as many Germans as Poles. These workers arrived at the camp in the morning and left in the evening after finishing their day's work.[20] They were employed because of the great amount of work to be done in the camp and the fact that there were hardly enough specialized workers among the prisoners. And civilians and prisoners worked together as often as not.[21]

Due to the growing number of prisoners and the work done outside the camp, the Germans found it impossible, despite their measures of vigilance and control (barbed wire fencing, watchtowers, police dogs, patrols, etc.), to prevent contact between the prisoners and the local population, which was exclusively Polish. Segments of the population formed part of the resistance organizations. In particular, the prisoner Kommandos working in the neighborhood of the camp frequently conversed with the Polish civilians. Upon occasion the civilians hid food, medicine and packages in previously arranged locations for the prisoners to pick up. The SS guards in charge of these Kommandos often looked the other way or else allowed themselves to be bought off in exchange for a good meal.[22]

As far as that goes, the possibilities for contacts were innumerable and extended to all the camps, subcamps and installations linked with the Auschwitz prison complex: such as the Rajsko subcamp, the fish nurseries of Harmeze, the camp for free workers, and the big industrial complex set up for the fabrication of synthetic rubber.[23]

Such contacts, above all those relating to the exchange of letters and packages, soon acquired a regular character. A clandestine organization in the camp would quickly set up a permanent connection enabling it to pass information regularly by letter to a resistance group in Cracow. Some 350 of these letters have been preserved in that city, “a fraction ofa much more significant total.”[24] The exchange of parcels between the camp and the outside grew to such an extent that, for example, a group of prisoners took it upon themselves to secretly make overcoats for AK partisan units operating in the vicinity of the camp. The packages were delivered by prisoners who worked in the agricultural fields or at nearby subcamps.[25]

Furthermore, the existence in Auschwitz of a clandestine radio transmitter has been confirmed. It was secretly installed in the cellar of block 20 in the spring of 1942. By means of contacts and couriers the leadership of the Silesia district of the AK succeeded in finding out the wavelength on which it was transmitting. The transmitter was in operation over a period of seven months, sending information about living conditions in the camp, in spite of which the Germans never managed to discover it. It stopped sending in the fall of 1942.[26]

There were even German personnel in the camp who collaborated with the resistance, such as Maria Stromberger, a nurse who carried messages from the camp to the heads of the AK in Cracow and Silesia and in turn brought in illegal correspondence, medicine, arms and explosives. Along with her, a group of SS guards offered to help the prisoners by acting as couriers.[27]

As the result of all that, there existed even in the first year of the camp's life a permanent, even though fragile, liaison between the camp and the intelligence section of the Cracow district of the secret army; by the end of 1941 a special cell had been set up at AK headquarters in Cracow for liaison with the Auschwitz camp.[28]

Clandestine contacts between Auschwitz and the outside were already so frequent and well organized by 1942 that Pilecki, founder of one of the resistance groups within the camp, was in “constant relationship” not only with the headquarters of the AK in Warsaw but also with the commandants of the districts of Cracow and Silesia.[29]

Moreover, the information secretly got out of Auschwitz was not limited solely to messages and reports prepared by the resistance. On occasion it included even entire volumes of official German documentation, such as, for example, two volumes of the “Bunker book” (Bunkerbuch) in which were noted all the admissions and discharges taking place in the camp prisons. These documents were smuggled out at the beginning of 1944.[30]

The ways by which information was passed were not always strictly clandestine. On numerous occasions messages left Auschwitz by much simpler means: carried by prisoners released by the Germans. Thus, to cite only a few cases connected with the resistance group founded by Pilecki, a first report went out by that means as early as November of 1940; in February and March of 1941, two others were sent; and at the end of 1941 another prisoner, Surmacki, was released unexpectedly and took with him to Warsaw a message from Pilecki himself.[31]

An unusually large number of prisoners was released during 1942: there were 952 releases during the first half of that year and 36 in the following six months. There was a number of releases in 1943 as well, and at the beginning of 1944 a considerable number of Jewish women were released, thanks to the intervention of a German industrialist.[32]

Another means by which information was passed to the outside was provided by the escapees. Sometimes the only purpose of the escape was to send messages out of the camp. An example of this kind of escape is that of Pilecki himself. This Polish officer decided to flee in order to persuade the heads of the AK to accept his plan for an uprising in Auschwitz and incidentally to provide information about the general situation in the camp. Pilecki escaped on 27 April 1943. Four months later, on 25 August, he reached Warsaw, where he contacted the officer who handled Auschwitz at AK headquarters.[33] Two other members of the Pilecki group had escaped previously with the identical objective of passing information to the headquarters of the AK.[34]

One may conclude from what has been stated above that because of its geographical situation and its special characteristics as a work camp open to civilian workers, Auschwitz was not the most adequate place for keeping secrets. If to that we add the efficiency with which the resistance groups worked, operating radio transmitters, enlisting the complicity of German guards, organizing escapes and utilizing released prisoners for their purposes, we should have to conclude that, for the Polish resistance, the Auschwitz camp was practically transparent. Accordingly, if there had been any massive extermination of Jews in Auschwitz, it would without doubt very shortly have been known in detail in the resistance headquarters in Warsaw.

2.4 Communications between Poland and London

All known sources indicate that the clandestine communications between Poland and London were on a regular basis and the information transmitted abundant. General Bor-Komorowski, the commandant of the AK, has pointed out that the secret reports:

were regularly dispatched by radio to London and in the years 1942-4 numbered 300 per month. They contained details concerning every aspect of the war. Apart from radio transmission, the essential facts of our Intelligence material were microfilmed and sent every month to London by courier.[35]

The information moreover went from the one place to the other with relative rapidity. The couriers traveled to London via Sweden or across western Europe and took several weeks, sometimes as much as two months, to arrive. Short messages, on the other hand, could be sent daily by radio to London. The Polish resistance had about a hundred radio transmitters at its disposal.[36]

Courier liaison with London was at first from 1941 until the end of July of 1942 maintained through several members of the Swedish colony in Warsaw who, when returning to Sweden, carried messages from both the AK and the Delegatura. The periodical reports on the situation within Poland (Sprawozdanie sytuacyjne z Kraju ) published by the PGE were based principally on material carried by the Swedes.[37]

Beginning with the second half of 1942, maintenance of communications was taken over by the Polish couriers. The most famous of these was Jan Karski (Kozielewski). Karski lived clandestinely in Warsaw in 1941 and 1942, devoting himself to psychological warfare (“black propaganda”) against the German occupiers. At the end of 1942 the leadership of the resistance ordered him to carry information to London. Karski left Poland secretly in October of 1942 and arrived in England the following month after traveling across Germany and France. In London he drafted a report which became famous. The Karski case was widely heralded in the Allied newspapers. Karski even made a propaganda tour of the United States, where he met with important figures, including President Roosevelt himself.

Jan Karski was very well informed.He had specialized in the study of the underground press. Cognizant of the great historical importance of the latter, he had put together probably “the richest collection of Polish underground material existent – newspapers, pamphlets, and books.”[38] Moreover, he had occupied a privileged observation post during his period of secret activities in Poland. Thanks to his job as liaison and to his frequent contact with the upper echelons of the resistance, both civilian and military, Karski “was able to survey the entire structure of the underground movement and to form a detailed picture of the situation as a whole in Poland.”[39] For that reason the leaders of the Polish underground sent him to London.

Another especially well-informed courier was Jan Nowak (Zdzislaw Jezioranski). Nowak was selected in 1943 to travel secretly to England, carrying the maximum possible information. With this in view, Nowak met that summer with the head of the Biuro Informacji i Propagandy (BIP – Bureau of Information and Propaganda) of the AK. The chief of the BIP was “in a sense minister of AK internal propaganda and policy. He controlled not only the military underground press, but also a widespread information network.”[40] On order of this person, Nowak met also with the section heads of the BIP, among them the head of the “Jewish section,” with all of whom he held “long and exhaustive” conversations over a period of one month.[41] In consequence, when he set off for London in the summer of 1943, Nowak had to be one of the persons best informed about what was going on in Poland.

Nowak arrived in London in December of 1943. Some months later, in mid-1944, he was ordered to return to Poland, where he arrived via parachute. He took part in the Warsaw uprising; after that was crushed, he managed to escape to London in January of 1945.

In short, if there had been a massive extermination of Jews in Auschwitz, the leadership of the resistance within Poland would not have failed to communicate it to their superiors in London, either by means of radio messages or by courier. Specifically, couriers such as Jan Karski and Jan Nowak men specially trained to carry the maximum possible information to London would certainly have communicated this terrible occurrence to the Polish authorities in exile.

2.5 Conclusion

It is impossible to accept that the PGE did not know what was taking place in Auschwitz. Apart from the obvious reasons, we must also take into account the level of capability the information and intelligence system of the Polish resistance had achieved. The AK had a most efficient intelligence system, which extended its tentacles even beyond Poland. It had sections assigned to researching the economic and military problems of the German forces in Poland and behind the Russian front, and others charged with obtaining information on the economic situation inside Germany, on ship movements in the ports of the Baltic and the North Sea, and on German morale.[42] For example, in the springof 1942 the leaders of the AK received detailed information on the number and position of the German divisions in the Ukraine and on the preparations the Germans were making to exploit the oil fields of the Caucasus.[43] The Poles also succeeded in obtaining top-quality information about some of the most highly guarded secrets of the Reich. Thus, in the spring of 1943, the AK received information that the Germans were carrying out experiments with mysterious weapons on Peenemünde, an island in the Baltic Sea. A few weeks later Polish agents had obtained detailed plans of the area of the experiments and had sent them to London.[44] Similarly, at the end of 1943 the intelligence service of the AK detected tests the Germans were making with the V-2 rocket in the area of Sandomierz (Poland), following which extensive reports on the secret new German weapon were sent to London. It so happens that the head of this secret investigation, Jerzy Chmielewski, had been under arrest in Auschwitz and had been released on bail in March of 1944. Chmielewski personally flew to London with the reports and several components of the V-2 rocket.[45]

The BIP of the AK, furthermore, from February of 1942 on had a Section for Jewish Affairs whose principal function was to collect information on the situation of the Jewish population.[46]

In sum, the intelligence system of the Polish resistancewas so well developed and so efficient that had there actually been a massive extermination of Jews in Auschwitz, it would have been known practically at once, in detail. In turn, detailed reports about the Auschwitz extermination would have reached London by courier in a relatively short time. Briefer reports would have been radioed immediately.

In addition, the massive annihilation of Jews in Auschwitz would have been so impossible to hide that, as author Jozef Garlinski has recognized, had there been no intelligence organization whatsoever, “the secret could still not have been kept.”[47]

All the facts clearly indicate, therefore, that if a slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Jews had taken place in Auschwitz, the PGE would necessarily have known of it.

3. AUSCHWITZ AND THE EXTERMINATION OF JEWS IN THE POLISH FORTNIGHTLY REVIEW

3.0 Preliminary Considerations

The fact which forcibly stands out after examination of the PFR collection – with the proviso that the issues of the fourth quarter of 1944 – could not be examined is that up to the 1st of May of 1945 (No. 115), there is not the slightest revelation that Jews were exterminated in Auschwitz. Only in issue 115, published when the war was practically over and the Allied atrocity propaganda about the German concentration camps was in full swing, do we find the first reference to the extermination of Jews in Auschwitz: it concerns the testimonies of two women who had been detained in the camp (see appendix 1).

In short, the official organ in English of the Polish Ministry of Information – its principal medium of information and propaganda abroad – did not reveal until the spring of 1945 the slightest indication that there had been a gigantic massacre of Jews, a slaughter moreover that had allegedly gone on continuously over a period of three years, from the beginning of 1942 to the end of 1944.

It must also be emphasized that the Auschwitz camp is repeatedly mentioned in the PFR, although there is no intimation that it was a place where Jews were being exterminated; and at the same time, while the extermination of Jews is frequently cited, there is never an indication that it was being carried out in Auschwitz.

Let us look, then, at these two aspects of the question more thoroughly.[48]

3.1 Auschwitz Is Mentioned Repeatedly, but Without Reference to Jewish Extermination There

Following now in chronological order are all the references to Auschwitz that appeared in the PFR up to May of 1945:

- Article “The Concentration Camp at Oswiecim” (no. 21, 1 June 1941, pp. 6-7).

The article points out that the telegrams that arrived from Auschwitz communicating the death of prisoners “first focused the attention of all Poland on this place of torture at the end of last year” (p. 6). It also indicates that the mortality rate was very high – between 20 and 25 per cent – due to ill treatment by the guards, to the exceptionally bad conditions, to the mass executions and to illness contracted because of the cold, overwork and nervous tension. Families were authorized to receive urns with the ashes of the deceased. The work conditions and food were horrible. The prisoners did not receive shoes until the 19th of September of 1940. There was only one towel for 20 persons. The work day started at 4:30 a.m. Two hundred prisoners had been released and had returned to Warsaw, although in a lamentable state of health, inasmuch as a “released prisoner is as a rule a sick man, tuberculous and with a weak heart, and in a state of nervous collapse” (p.7).

Let us emphasize that by the end of 1940 “the attention of all Poland” was centered on Auschwitz and that by the middle of 1941 the PGE already had detailed data regarding the interior of Auschwitz, though invested with the characteristic tone of atrocity propaganda. - Article “Oswiecim Concentration Camp” (no. 32, 15 November 1941, pp. 5-6).

According to the author of the article, the Auschwitz camp, “which is the largest in Poland, merits a detailed description' (p.5). Next, as in the previous article, the general situation of the camp is described. The barracks had chinks and lacked heating. The prisoners lacked their own towels, which spread infections. Moreover, many persons 'suffering from venereal diseases are deliberately sent to the camp” (p. 5). Work began at 5 a.m. and was exhausting. The prisoners had to work even when they were ill. The roll calls were terrible: they were the cause of frequent deaths. A system of collective responsibility had been imposed on the prisoners, so that punishments were frequent and were applied by means of a large repertory of tortures. The winter of 1940-1941 was distinguished by its high mortality rate, with figures running between 70 and 80 corpses per day (one day 156). The death rate went down in the spring and following summer to 30 persons a day. At the end of November of 1940 there were 8,000 Poles in Auschwitz, divided into three groups: political prisoners, criminals, and priests and Jews. Those in the last group were the worst treated “and no member of the group leaves the camp alive” (p. 6).

The most important thing to point out here is that at the end of 1941 the PFR was in a position to publish “a detailed description” of what was happening in Auschwitz. - Article “German Lawyers at Work” (no. 40, 15 March 1942, p. 8).

This concerns the text of a radio message from Stanislaw Stronski, Polish Minister of Information, which was broadcast by the BBC's Polish new service on 11 March 1942. Stronski points out that all “the German war criminals, from the degenerate Frank in the Polish Wawel to the degenerate overseers in Oswiecim concentration camp, are responsible for the fact that in a land in which their very existence is a crime, they are murdering a hundred for one.” - Article “Pawiak Prison in Warsaw and Oswiecim Concentration Camp” (no. 47, 1 July 1942, pp. 2-3).

In this article it is said that besides the main camp built in the vicinity of Auschwitz, there was another nearby “in which the brutalities are so terrible that people die there quicker than they would have done in the main camp” (p. 2). The prisoners said this camp was “paradisiac” [paradiesisch = paradisiac/heavenly] “presumably because from it there is only one road, leading to Paradise” (p. 2).

The article here no doubt refers to the Birkenau camp, the construction of which had begun in October of 1941.[49]

The prisoners of both camps, the author of the article goes on to say, were annihilated in three ways: “by excessive labour, by torture, and by medical means” (p.2). The prisoners of camp “paradise” in particular had to do very hard work “chiefly in building a factory for artificial rubber production near by” (p.2).

In fact, in April of 1941 the Germans had begun constructing a large chemical complex of the I.G. Farben company designed for the manufacture of synthetic rubber and gasoline. The Auschwitz prisoners were used as laborers in the construction of this complex.[50]

The Germans, the writer of the article continues, made use of a “scientific” method for killing prisoners. It consisted in the administration of injections which slowly affected the internal organs, especially the heart. Moreover, it is “universally believed that the prisoners are used for large-scale experiments in testing out new drugs which the Germans are preparing for unknown ends” (p. 2). In the context of the experiments conducted on the prisoners, the use of poison gas with a homicidal purpose is described:

It is generally known that during the night of September 5th to 6th last year about a thousand people were driven down to the underground shelter in Oswiecim, among them seven hundred Bolshevik prisoners of war and three hundred Poles. As the shelter was too small to hold this large number, the living bodies were simply forced in, regardless of broken bones. When the shelter was full, gas was injected into it, and all the prisoners died during the night. All night the rest of the camp was kept awake by the groans and howls coming from the shelter. Next day other prisoners had to carry out the bodies, a task which took all day. One hand-cart on which the bodies were being removed broke down under the weight (p. 2).

Something paradoxical would seem to have been produced here: the PFR knew – and published – data on the incidental extermination of a thousand persons at a time when it was presumably completely unaware of the massive and regular extermination of hundreds of thousands of Jews throughout 1942, 1943 and 1944.

On the other hand, the thesis of the extermination of a thousand Russians and Poles in the underground shelter of Auschwitz and its later evolution in the “Exterminationist” doctrine has been completely discredited.[51]

The article also points out that a section for women had recently been formed in Oswiecim (p. 2). From that may be inferred that the article contained information on Auschwitz from at least as late as March of 1942, since the first transport of women arrived at the camp on the 26 March 1942.[52]

Finally, the article records that Oswiecim had the capacity for 15,000 prisoners, “but as they die on a mass scale there is always room for new arrivals” (p. 3). - “Furor germanicus” (no. 47, 1 July 1942, p. 8).

This is the title of a talk by Stanislaw Stronski broadcast by the Polish news service of he BBC on 1 July 1942.

The furor germanicus is produced, according to Stronski, because the “Germans are raging, ” and now that they “are satiating their age-old lust for domination, they are swimming in the blood of the defenceless and luxuriating in the torments of their victims.” According to Stronski, the Polish government had at that time “a very clear picture of the methods of government, i.e., the German persecutions and barbarities in Poland during the first six months of this year” and that the “latest reports from Poland confirm the sombre news which has come in great detail during the last six months, and convey the incredible dimensions of the crimes.” These reports had to be truly recent, since the introductory note to this issue indicated that it corresponded “to the latest possible date” and that for the most part it “relates to the situation at the beginning of June, less than a month ago” (p. 1).

The only reference to Auschwitz in Stronski's radio message is the following: “In addition to the torture camps for men, with Oswiecim as the chief, there are now torture camps for women, such as the one near Fürstenburg (Mecklenburg) known as Ravensbrück.”

So that in spite of this “very clear picture” of the situation in Poland and the recentness of the information, the PGE seemed not to know of the killing of Jews that was supposedly being carried out in Auschwitz from the beginning of 1942.[53] - Press conference statement of the Polish Minister of the Interior, Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, on 9 July 1942 (no. 48, 15 July 1942, pp. 4-6).

In his extensive statement referring to the latest events that had occurred in Poland and in which he emphasizes that the furor teutonicus had reached “a murderous paroxysm” (p. 6), Mikolajczyk only mentions Auschwitz in passing: “In the concentration camp at Oswiecim itself the number of prisoners held has risen in the course of three months by 8, 000” (p.5). - In the article “Concentration Camps” (no. 48, 15 July 1942, p. 3), Auschwitz appears in an account of 23 concentration camps “where Poles are confined.”

The article indicates that groups of prisoners are continually being sent to Oswiecim from all the prisons in Poland and specifically some hundreds of them in the months of March and April of 1942. There are notices of the demise of prisoners “who are unable to stand up to the rigours of the camp” and indication also that large groups of prisoners go to work every day on the construction of a synthetic gasoline plant in the immediate area. Lastly, precise information is given on deceased prisoners. - In another article, “Polish Youth in the War” (no. 56, 15 November 1942, p. 8), Auschwitz appears as one of the places where young Poles 12 to 18 years of age were interned.

- The article “Children in Prisons and Concentration Camps” (no. 77, 1 October 1943, p. 5), reports:

Other reports from Poland say that children under the age of 12 sent with the transports to the camp at Oswiecim are not accepted by the camp authorities, but are killed on the spot, in special gas chambers installed for the purpose. This information first came to hand in December, 1942, and has since been repeated in several reports.

From the context we infer that this concerns Polish children. This is the only reference to gas chambers in Auschwitz prior to 1945.

3.2 The Extermination of Jews Is Mentioned Repeatedly, but with No Reference to Auschwitz

Following in chronological order are the references to the extermination of Jews that appeared in the PFR up to May of 1945:

- The article “Pawiak Prison in Warsaw and Oswiecim Concentration Camp” (no. 47, 1 July 1942, p. 3) reports: “It is also well known in Poland that last year a party of Jews was taken off to the neighbourhood of Hamburg, where they were all gassed.”

So the alleged fate of a party of Jews in Hamburg was “well known” in Poland, whereas the routine slaughter of Jews that was supposedly taking place in Auschwitz was not known – or not revealed. - Article “Destruction of the Jewish Population” (no. 47, 1 July 1942, pp. 4-5).

According to the writer, the first manifestations of the new repressive measures against the Jews, in the form of mass shootings, took place in Nowy Sacz, Mielec, Tarnow and Warsaw. A little later the Lublin ghetto was obliterated. The German press said that the ghetto had been transferred to the locality of Majdan Tatarski, “but in fact almost the entire population was exterminated” (p. 4). A certain number of Jews from the ghetto were put into freight cars that were taken outside the city “and left on a siding for two weeks, until all inside had perished of starvation” (p. 5). However, most of the Lublin Jews were taken to Sobibor, “where they were all murdered with gas, machine-guns and even by being bayoneted” (p. 5). Detachments of Lithuanian auxiliary police (szaulis) had been brought to Poland to carry out thesemass exterminations. It is also noted that there was confirmation of the “complete extermination” of the Jews in the areas of the East. Cities such as Molodeczno and Baranowicze had been left completely judenfrei (free of Jews) (p. 5). Some thousands of Jewish children were murdered in Pinsk in the fall of 1941. In turn, in March of 1942, 12, 000 Jews were liquidated in Lwow, where wholesale crimes were still going on. In the cities of Southeast Poland, “Ruthenian [or Ukrainian; Ed.] organizations organize hunts after the Jews who are still hiding in numbers in the villages” (p.5). - On 8 July 1942 the Polish National Council, a sort of parliament-in-exile, in a resolution directed to the parliaments of the free nations, alerted them to the “newly revealed facts of the systematic destruction of the vital strength of the Polish Nation and the planned slaughter of practically the whole Jewish population” (no. 48, 15 July 1942, p. 3).

- The following day, 9 July, a press conference took place in which several Polish dignitaries living in exile participated (no. 48, 15 July 1942. pp. 4-8). Mikolajczyk, the Minister of the Interior, said that the “wholesale extermination of the Jews” had begun (p. 4). He said there had been a number of killings of Jews in the Belzec and Trawniki camps, where “murders are also carried out by means of poison gas” (p. 6). He also cited killings of Jews in some twenty localities, with figures of the victims, depending on the location, of from 120 to 60, 000. The methods of extermination were by machine guns, hand grenades and poison gas (p. 6).

At the same press conference, Dr. Schwarzbart, a Jewish representative on the Polish National Council, mentioned killings in about thirty places, with figures of the victims, depending on the location, that varied between 300 and 50, 000 (pp. 7f.).

In short, between these two notables, some fifty places in Poland were mentioned where there allegedly were slaughters of Jews. Significantly, Auschwitz – or Oswiecim in accordance with the Polish designation – does not appear in any of these accounts. - Number 57 of the PFR, published on 1 December 1942, is a monograph devoted to the extermination of the Jews of Poland. A large part of its contents makes reference to the deportation of the Jews of Warsaw begun in the summer of 1942. In this connection it is stated that the Jews were deported in trains in which the floors of the freight cars were covered with quicklime and chlorine (p. 3). The deportees were taken to three execution camps: Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor. “Here the trains were unloaded, the condemned were stripped naked and then killed, probably by poison gas or electrocution” (p. 3).

This issue also contains an “Extraordinary Report from the Jew-extermination Camp at Belzec” (p. 4). This report allegedly came from a German employed in the camp. It says that the place is overseen by Ukrainian guards. The deportees arrived in trains and no sooner had they arrived than they were taken out of the train, stripped, and ordered to take a bath. In reality they were taken to a big building “where there is an electrified plate, where the executions are carried out.” Once electrocuted, the victims were taken by train out of the camp enclosure and thrown into a pit 30 meters deep. This pit had been dug out by Jews, who were also assassinated once they had finished their task. In their turn, the Ukrainian camp guards “are also to be executed when the job is finished.”

Surprisingly, the PFR had managed to publish a report from the interior of Belzec camp thanks to the revelations of a German employee and in spite of security measures severe to the extreme of liquidating the Ukrainian guards periodically to avoid witnesses. Yet the PFR had not thus far published even a single indication that Jews were being murdered in Auschwitz, notwithstanding that this supposed slaughter had started at the beginning of 1942 and that there were very abundant sources of information about the camp.

But what is most important to make clear is that in an issue in the form of a monograph on the extermination of Jews in Poland and published a year after the supposed killings in Auschwitz began, the name of this concentration camp is not mentioned even a single time. - Issue no. 71 of the PFR, published on 1 July 1943, is also a monograph devoted to the extermination of the Jews of Poland. Its sole contents are the testimonies of two Jewish women who escaped from Poland in the fall of 1942. The first testimony is titled “Agony of the People Condemned to Death” (pp. 1-7) and narrates the vicissitudes of a Jewish woman and her family in various ghettos. The second report bears the title “What Happened in the Radom Ghetto” (pp. 7-8) and relates details of the life there.

Auschwitz is not mentioned in this issue either, and this notwithstanding that during the period in question what was happening there could not possibly have been concealed, since the Exterminationists maintain that from the summer of 1942 an annihilation on a large scale, due chiefly to the arrival of large convoys of Jews from Slovakia, France, Belgium and Holland, was being carried out there.[54] - Finally, in January of 1944 a bare notice gives details of a revolt in which “Jews held in the death camp at Treblinka revolted in a desperate struggle against their murderers.” The revolt had taken place at the beginning of August of 1943 (no. 84, 15 January 1944, p. 4).

4. CONCLUSION

4.0 Preliminary Considerations

I believe that throughout this study two facts have remained sufficiently clear:

- that the PGE had sufficient sources of information available to it to know in detail what was going on in Auschwitz;

- and that the PFR, the principal propaganda organ in English of the Ministry of the Interior of the PGE, made no mention that a slaughter of Jews was taking place in Auschwitz until practically the end of the war, in May of 1945. In sum, the PFR reported extensively on this concentration camp, but never to the effect that Jews were being annihilated there; and in the same fashion, it alluded frequently to the extermination of Jews but never said that it had taken place in Auschwitz.

The truth is that the PFR, which was able to know – and no doubt did know – what was occurring at Auschwitz, said absolutely nothing about the extermination of Jews that had supposedly been carried out in this camp during a period of more than three years, from 1942 to May of 1945.

The next step consists in asking oneself why the PFR failed to disclose anything about this massacre when, according to all the evidence, it must have known of it in detail.

In my opinion, there are three considerations which can be put forward to justify, or attempt to justify, the silence of the PFR:

4.1 The PGE Knew What Was Going on in Auschwitz, but Did Not Wish to Broadcast It and Thereby Relegate the Suffering of the Poles to a Matter of Secondary Importance

This argument has been advanced by the Israeli professor David Engel. According to Engel, the Poles had a powerful political reason for not centering the attention of the world on the extermination of Jews in Poland: widespread publicity about this event would have made the sufferings of the Poles seem minor in comparison, which could earn them less attention and sympathy from the international community. And so, Engel says, information about the “final solution” was filtered through to the West by the PGE only when such information could exacerbate hatred of the Nazi regime in general and at the same time not relegate the suffering of the Polish people to a lower plane.

In particular, and with respect to Auschwitz, the Polish authorities considered this camp a symbol of the tribulations of the Poles themselves, and thought that it might cease to be so if information about the massive annihilation of the Jews that had occurred there should be broadcast worldwide.[55]

This argument does not seem convincing, for various reasons. In the first place, news about the extermination of Jews in Poland did not occupy a secondary position either in the PFR or in the official documents of the PGE (see Appendix 2). On the contrary, the prominence given news relating to the extermination of Jews over other news in the PFR is quite apparent, especially in the second half of 1942 (see 3.2). In this connection, various official declarations of the PGE published in the PFR place more emphasis on the atrocities committed against the Jews than on those committed against the Poles themselves. Let us look at a few examples:

- In a press conference held on 9 June 1942, Minister of the Interior Mikolajczyk, said: “Still worse is the situation of the Jews… Hunger, death and sickness are exterminating the Jewish population systematically and continually” (no. 48, 15 July 1942, p. 6).

- At the same press conference, Dr. Schwarzbart, member of the Polish National Council, pointed out that the organized killings of Jews “surpass the most horrible examples in the history of barbarism” (no. 48, 15 July 1942, p. 7).

- Mikolajczyk, speaking in the name of the PGE, stated on 27 November 1942:

The persecutions of the Jewish minority now in progress in Poland, constitute however, a separate page of Polish martyrology.

Himmler's order that 1942 must be the year of liquidation of at least 50 per cent of Polish Jewry is being carried out with utter ruthlessness and a barbarity never before seen in world history (no. 57, 1 December 1942, P. 7).

- Lastly, a resolution of the Polish National Council on 27 November 1942 calls attention to “the latest German crimes, unparalleled in the history of mankind, which have been carried out against the Polish nation, and particularly against the Jewish population of Poland” and accordingly condemns “the extermination of the Polish nation and other nations, an extermination the most appalling expression of which is provided by the mass murders of the Jews in Poland and in the rest of Europe which Hitler has subjected” (no. 57, 1 December 1942, p. 8).

So if the reports about atrocities committed against the Jews had become of primary concern, at least during the second half of 1942, it is not logical that the PFR should not even mention the name of Auschwitz, where, supposedly, more atrocities against the Jews were being committed. Furthermore, by the end of the second half of 1942 the Auschwitz camp had ceased to be a kind of symbol of the suffering of the Poles, at least insofar as the PFR is concerned. In fact, from 1 July 1942 on there are scarcely any references to the existence of Auschwitz in the publication. Auschwitz during that time was not a symbol of anything. It practically disappeared from the pages of the PFR, submerged in fact by the avalanche of reports about the extermination of Jews.

If anything, the Poles had a strong political reason for putting a special emphasis on the propaganda about atrocities against the Jews. The Poles in exile, for reasons we shall immediately go into, longed for a rapprochement with world Jewry in order to obtain the support of this powerful international force.

After the Soviet aggression against Poland in September of 1939, the USSR annexed important portions of Polish territory. Since 1941, the PGE had based its strategy with respect to the USSR on the nonrecognition of the Soviet annexation of those territories by England and the United States. The Anglo-Soviet treaty of 1942, however, weakened this hope. As even Engel acknowledges:

In this situation the Poles were more in need of influential friends than ever before. In view of their belief in the crucial role played by Jewish organizations in the formation of British and American opinion, they had to continue to try to win the Jews to their side, no matter how much effort would be required to do so, and almost at any cost. Hence the latter half of 1942 was a period of intensified Polish overtures to Western and Palestinian Jewry.[56]

Consequently, if the PGE needed Jewish support at practically any price, it would not have been logical for it to suppress news reports about a slaughter of Jews in Auschwitz. On the other hand, the dissemination of this news in the context of the propaganda concerning atrocities against the Jewish population would no doubt have made it easier for the PGE to approach the Jewish international circles whose support it so eagerly sought.

Moreover, and on quite another plane, passing over Auschwitz in silence was counterproductive for the PGE's one-time idea of bombing this concentration camp. In fact, as early as January of 1941, the PGE requested of the British government that the RAF bomb Auschwitz. The proposal was rejected, but, as Engel also recognizes, there is no reason to suppose that the Poles had since that time abandoned the idea that the activities of the camp could be paralyzed by military action on the part of the West. He writes:

In this context, a serious Polish campaign to publicize the especially egregious fate of Auschwitz's Jewish prisoners might conceivably have aroused sufficient anger within Western public opinion to force the British government to reconsider its attitude [with regard to the bombing of Auschwitz].[57]

In short, it is not true that the exterminationof the Jews was of secondary importance in the propaganda policy of the PGE, since in fact the PFR did give it extensive coverage. Nor is it true that the PGE considered Auschwitz a symbol of the suffering of the Poles that it must, in its propaganda, put before news of the extermination of the Jews. We have already seen, on the contrary, that from the second half of 1942 on the PFR practically forgot about Auschwitz in order to feature precisely the news reports of the extermination of Jews. Ultimately, the PGE had the greatest possible political interest in emphasizing the propaganda about atrocities against the Jews. Accordingly, it would have been logical for the PGE to build up the role played by Auschwitz in these supposed atrocities.

In view of all the foregoing, we must conclude that this first reason alleged to justify the silence of the PFR is not valid. It would seem, therefore, that the reason for the silence of the PFR must be sought elsewhere.

4.2 The Secret Reports on the Extermination of Jews in Auschwitz Reached London Very Late, and Therefore Were Published at the End of the War

This is the explanation provided for the fact that the first news about the killings of Jews in Auschwitz appeared in the PFR on the 1st of May of 1945 (see Appendix 1).[58]

Simply put, this argument would mean that the reports on the annihilation of Jews in Auschwitz, which supposedly got under way at the beginning of 1942, did not reach London until three years later.

Examination of the available data, however, makes this notion easy to refute. Thus, for example, an article with detailed information about Auschwitz up to September of 1940 was published by the PFR in June of 1941 (no. 21, 1 June 1941, pp. 6f.). Engel has shown likewise that the first clandestine report about Auschwitz left Poland on 30 January 1941 and reached London on 18 March of the same year.[59] It has already been indicated previously (see 2.4) that communications between Poland and London flowed smoothly. They were instantaneous if the messages were transmitted by radio and generally took a few months if they were sent by courier. With regard to radio messages, there exists a radiogram sent from Poland by clandestine radio station “Wanda 5” on the 4 March 1943 which contains news about Auschwitz up to 15 December of 1942.[60] Another radiogram, sent by the clandestine radio station “Kazia” on 7 June 1943, contains news from inside Auschwitz up to April of the same year.[61] These offer conclusive evidence that reports concerning Auschwitz were known in London within the space of a few months.

Consequently this justification, to explain the silence of the PFR, can not be accepted either.

4.3 The PFR Did Not Report on the Extermination of Jews in Auschwitz Simply Because No Such Extermination Occurred

That, in the opinion of this writer, is the appropriate conclusion to be drawn from all the available facts. Let us briefly review these facts:

- the PGE had the capability of knowing, through numerous channels of communication, what was going on inside Auschwitz; if a physical extermination of Jews had been systematically carried out in the camp, the PGE would doubtless have known of it in a very short space of time;

- the PGE did not, until the end of the war, publishin the PFR, its principal propaganda organ in English, any information to the effect that a great slaughter of Jews had taken place in Auschwitz, and the silence of the PFR is shared by a most important official declaration of the PGE as well (see Appendix 2);

- the PGE, and hence the PFR, had no motive for suppressing reports of atrocities committed against the Jews; on the contrary, this aspect constituted one of the central points of its propaganda.

The only explanation that would seem to fit, then, to justify the silence of the PFR is that a slaughter of Jews never took place in Auschwitz, at least none significant enough to be publicized.

This is the conclusion derived from the rigorous application of the historians' argument ex silentio. According to this, a given historical assumption is considered not to have happened when it is not cited by contemporaries, always supposing these two circumstances to be present:

- the contemporary authors could know and had to know the fact in question; and

- they ought to have reported it.[62]

Thus, for example, it is admitted that the Franks did not hold regular assemblies, because the principal chronicler of the period, Gregory of Tours, did not mention them and doubtless would have if they had existed.[63]

These two necessary conditions can be applied perfectly to our case:

- the PFR could know and had to know that the Jews were being annihilated on a massive scale; and

- it ought to have reported it, since the question of the extermination of the Jews constituted one of the central points of its propaganda.

And if it did not report it, it was because in all probability a massive extermination of Jews never took place. This, therefore, is the only satisfactory explanation for the silence of the Polish Fortnightly Review.

Appendix 1

Issue 115 (1 May 1945) of the Polish Fortnightly Review

In this issue, for the first time, informationwas published concerning the extermination of Jews in Auschwitz. This revelation occurred more than three months after the arrival in Auschwitz of the Soviet troops, and at a time when the war was practically over (it ended officially in Europe on the 8th of May). At that time a tremendous worldwide propaganda campaign was being waged on the atrocities committed in the German concentration camps already occupied by the Allies (principally Bergen-Belsen and Buchenwald); a few months earlier, in November of 1944, the War Refugee Board, an official U. S. organization charged with rescuing and assisting the victims of the war, had published three testimonies in which were described massive killings of Jews that had taken place in Auschwitz.[64]

Issue number 115 of the PFR, bearing the generic title “Polish Women in German Concentration Camps, ” is devoted exclusively to Auschwitz. It contains two testimonies of women prisoners, an account of women “gassed” and a brief report on medical experiments.

1. First testimony: “An Eye-Witness's Accountof the Women's Camp at Oswiecim-Brzezinka (Birkenau). Autumn, 1943, to Spring, 1944” (pp. 1-6).

The introductory note indicates without embellishment that this is the testimony of a woman, an eyewitness, who gives an account of things that happened in the second half of 1943 and the beginning of 1944. It indicates also that the document reached London “by devious routes” (p. 1).

A brief examination of the text in question permits the conclusion that it is without value as a historical source and is nothing but a propaganda production.

In the first place, no details whatsoever are provided as to its provenance. Who wrote it, when and where it was written, or through what agency it reached London is not revealed. If the war was practically at an end, what danger could the author be supposed to incur by revealing her name and personal details? Nor is there any indication as to whether this person was liberated from Auschwitz, whether she escaped, or whether she sent her report clandestinely while still a prisoner. The omission of these details as to the origin of the document, without evident reason, makes it more than suspect. Furthermore, the writer also fails to mention any dates, such as the date of her arrival at the camp; or what duties she discharged while at the camp.

With regard to her description of life in the camp, the witness relates happenings that are very hard to believe. For example, she says she was in the “Sauna” just at the time a special selection of women prisoners for the camp brothel took place, at which she also watched an interpretation of pornographic songs by a prisoner who was a former cabaret singer, and the execution of a Cossack dance by a Gypsy. Both women were completely naked (p. 4). She also managed to be present at an inspection in the hospital, during which a German doctor, who was stressing the importance of maintaining good hygienic conditions, carefully examined the walls for dust or cobwebs while appearing to be indifferent to the piles of corpses and the lack of medicines and water (p. 4).

The witness also states that she saw the crematory furnaces, which never ceased operation, and from the chimneys of which continuously poured great clouds of smoke, and flames up to 10 meters high (p. 5). The incessant activity of the crematories was due to the annihilation of the Jews. Trains arrived every day from all over Europe. Ten percent of the passengers were interned in the camp; the rest went straight to the gas chamber (which is always referred to in the singular). She also claims to have seen the actual extermination in the gas chamber of 4, 000 Jewish children from the ghetto of Terezin (Theresienstadt). In fact, according to the witness, the gas did not kill but only stunned them, since it was expensive, and the Germans wished to be sparing with it. Consequently the victims woke up in the trucks transporting them from the gas chamber to the crematory and were flung into the fire alive (pp. 5f.).

The author of this testimony, no doubt conscious of the enormities she is relating, repeats several times that her information is strictly true, that she has seen it all personally. and that, besides, this is only a small part of the truth (pp. 2 and 6).

In short, the first document published by the PFR on the extermination of the Jews of Auschwitz is historically unacceptable.

2. Second testimony: “Report Made by a Girl Fifteen Years Old” (pp. 6-7).

The introductory note says that this is the testimony of a Polish girl regarding her stay in the Birkenau women's camp during the second half of 1943 and the beginning of 1944 (p. 1). Just as in the previous case, the facts as to the origin of the document are not stated. Judging from the language and the style in which it is written, it does not seem to be the work of a fifteen-year-old girl.

With regard to the contents, the most important thing to note is that it contains not the slightest reference to the extermination of Jews. In only one passage is allusion made to the “gas chamber, ” in which those selected at roll call because of their poor physical condition are going to end up. The rest of the document is surprisingly objective, given the circumstances and the time in which it was published. Because of its interest we reproduce it below. [pages from Polish Fortnightly Review numbered 53a and 53b]

3. Other information (p. 8).

Issue 115 also contains an account of women annihilated with poison gas at Birkenau in 1943, in which information is given month by month from February of 1943 to December of 1944. The victims are sorted into three groups: Poles, Jews and others. According to this information, the number of Polish and “other” women is much larger than that of the Jewish women.

Lastly, there is a brief report about medical experiments performed on women in block number 10 of Auschwitz.

Appendix 2

An Official Document of the Polish Government-in-Exile:

“The Mass Extermination of Jews in German Occupied Poland” (Archives of the SPP, 2318)

This concerns an official document of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the PGE published in London in December of 1942. It contains various official texts and declarations of the PGE put out between 27 November and 17 December of 1942.

The document claims to be bringing together the “most recent reports” received from Poland “during recent weeks” on the “new methods of mass slaughter applied during the last few months” (pp. 4-5).

The information about the exterminationof Jews contained in this document is represented as complete. At the outset, the document establishes a chronological account of the principal milestones in the extermination policy of the Germans. Thus, it notes that the first steps leading to the extermination phase were taken as early as October of 1940, when the Warsaw ghetto was established (p. 5). Later, beginning with the German-Soviet war, great massacres of Jews were carried out, especially in the eastern provinces. Around the middle of July of 1942, the word was given to commence the process of liquidation, “the horror of which surpasses anything known in the annals of history” (p. 6). Finally, at the end of July of 1942, the deportation of the inhabitants of the Warsaw ghetto to the extermination camps began (pp. 8-9).

The document enumerates the principal places where the killings were being carried out and describes the extermination methods. It says that the deportations from the Warsaw ghetto were directed toward the extermination camps of “Tremblinka [sic], Belzec and Sobibor, “employing freight cars whose floors were covered with quicklime and chlorine. Upon arrival at the camp the survivors from the freight cars were murdered by various means, “including poison gas and electrocution, ” after which they were buried (pp. 8-9). In Chelm (Kulmhof) the Germans were also using poison gases (p. 6). In other places such as Wilno, Lwow, Rowne, Kowel, Tarnopol, Stanislawow, Stryj and Drohobycz, the method was shooting (p. 6).

The most important thing to note is that this official document, which claims to have exhaustive and very recent information on the extermination of Jews in Poland, does not once mention Auschwitz. It must be taken into account, moreover, that this text was published in December 1942, practically a year after the supposed extermination of Jews in Auschwitz had been initiated and six months after the “killings” took on a systematic character with the arrival of large convoys of Jews from France, Slovakia, Belgium and Holland.

The document further contains a report of great interest relative to the deportation to Poland of Jews of other countries. Specifically, it speaks of “the many thousands of Jews whom the German authorities have deported to Poland from Western and Central European countries and from the German Reich itself” (p. 4). These Jews brought from abroad had been concentrated in ghettos (p. 15). According to the thesis generally accepted today, a good part of these Jews were to end up at Auschwitz. For example, it is stated that up to 1 December 1942, 45 convoys of Jews arrived at this concentration camp from France, 17 from Belgium, 27 from Holland and 19 from Slovakia.[65] Specifically, all the Jews of France and Belgium who were deported to Poland in 1942 supposedly ended their journey in Auschwitz.[66] So that, estimating half a thousand persons per convoy, around 100,000 Jews from these countries would have arrived at Auschwitz in 1942. Of this number, the partisans of the Exterminationist thesis affirm, only a small part were considered fit for work and interned in the camp, and the rest sent without further ado to the gas chambers.

But if the PGE knew that the Jews of Western countries were being deported to Poland, they would doubtless have to know that a good part of them were going to end up at Auschwitz. The silence of the PGE is therefore very significant and suggests a very different hypothesis: that many of the Jews deported to Poland from France, Belgium, Holland and Slovakia during 1942 never reached Auschwitz. The fact that in the document we are discussing it is indicated that these Jews were concentrated in ghettos reinforces this hypothesis.[67]

Notes

| [1] | Engel, D., In the Shadow of Auschwitz, pp. 192, 172. |

| [2] | Duraczynski, E., Polish Government in Exile, pp. 1177-1178. |

| [3] | Garlinski, J., Poland, SOE and the Allies, pp. 21-29, 90. |

| [4] | Duraczynski, E., Delagatura, pp. 356f. |

| [5] | Duraczynski, E., Armia Krajowa, pp.88f. |

| [6] | Jarosz, B., Le mouvement de…, pp. 145-147, 150. |

| [7] | Jarosz, B., Le mouvement de…, pp. 158. |

| [8] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 97f. |

| [9] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 123. |

| [10] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 110. |

| [11] | Jarosz, B., Le mouvement de…, p. 110. |

| [12] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, p. 175. |

| [13] | Poles of German origin who had chosen to hold German nationality after 1939. |

| [14] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, p. 205. |

| [15] | Jarosz, B., Le mouvement de…, p. 151. |

| [16] | No. 84, 15 January 1944, p. 5. |

| [17] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, p. 253. |

| [18] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 46, 153. |

| [19] | Laqueur, W., The Terrible Secret, pp.22f. |

| [20] | Laqueur, W., The Terrible Secret, pp.24. |

| [21] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 43 |

| [22] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 43-45. |

| [23] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 155ff. |

| [24] | Langbein, H., Hommes et femmes à Auschwitz, p. 252. |

| [25] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, p. 126. |

| [26] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 100f. |

| [27] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 206-208. |

| [28] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, p. 46. |

| [29] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 102, 143. |

| [30] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, p. 230. |

| [31] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 54f, 112. |

| [32] | Laqueur, W., The Terrible Secret, p.169. |

| [33] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 167-173. |

| [34] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, pp. 101-103. |

| [35] | Bor-Komorowski, T., The Secret Army, p. 150. |

| [36] | Laqueur, W., The Terrible Secret, pp.103, 107. |

| [37] | Laqueur, W., The Terrible Secret, pp.103f. |

| [38] | Karski, J., Story of a Secret State, p. 217. |

| [39] | Karski, J., Story of a Secret State, p. 253. |

| [40] | Nowak, J., Courier from Warsaw, pp.164f. |

| [41] | Nowak, J., Courier from Warsaw, pp.166, 172-174. |

| [42] | Bor-Komorowski, T., The Secret Army, p. 150. |

| [43] | Bor-Komorowski, T., The Secret Army, pp. 122f. |

| [44] | Bor-Komorowski, T., The Secret Army, p. 151. |

| [45] | Garlinski, J., Poland, SOE and the Allies, pp. 150-154. |

| [46] | Duraczynski, E., Armia Krajowa, p.89. |

| [47] | Garlinski, J., Fighting Auschwitz, p. 89. |

| [48] | All of the quotations which follow, unless otherwiseindicated, are from the PFR, with the issue, date and corresponding page numbers given in parentheses following each quotation. |

| [49] | Czech, D., Kalendarium der Ereignisse im…, p. 159. |

| [50] | Czech, D., Kalendarium der Ereignisse im…, p. 86. |

| [51] | See in this respect the work of Mattogno, C., The First Gassing at Auschwitz. |

| [52] | Czech, D., Kalendarium der Ereignisse im . . , p. 189. |

| [53] | Rudolf Höss, the first commandant of Auschwitz, notes in his memoirs that the extermination for Jews in this camp had begun “probably” in September of 1941 or in January of 1942 (Höss R., Kommandant in Auschwitz, pp. 159f. |

| [54] | Buszko, J., Auschwitz, pp. 114-115. |

| [55] | Engel, D., In the Shadow of Auschwitz, pp. 177, 201-203. |

| [56] | Engel, D., In the Shadow of Auschwitz, p. 147. |

| [57] | Engel, D., In the Shadow of Auschwitz, p. 209. |

| [58] | Or in the fall of 1944, should the issues of that period – which I have not been able to find – have information on the matter. |

| [59] | Engel, D., In the Shadow of Auschwitz, p. 305. |

| [60] | The text of the English translation of this message, made in London, is dated 31 March 1943. (Archives of the SPP, 3.16). |