Disney’s $140 Million Dud

Movie Review

Pearl Harbor. (2001) Genre: film (war, drama). Length: 183 minutes. MPAA rating: PG-13. Starring: Ben Affleck, Josh Hartnett, Kate Beckinsale, Alec Baldwin, Cuba Gooding, Jr., Mako, Jon Voight. Director: Michael Bay. Producer: Jerry Bruckheimer. Screenplay: Randall Wallace. Released by: Buena Vista. Grade: D.

Scott L. Smith holds a B.A. in history from Idaho State University. He served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and has worked as a radio-television engineer.

At three hours long, Pearl Harbor strains to be an epic. Unfortunately, it falls short both as epic fact and epic fiction. The movie’s chief focus is on the feelings and motives of a few young Americans in 1941, with a well-known Japanese attack thrown in. The 45-minute-long battle sequence just suffices to make Pearl Harbor a passable summer action movie. As for the rest of the film, it’s a stitched-together mini-series suffers by comparison to the made-for-TV remake of From Here to Eternity, let alone to the original.

Nor is Pearl Harbor a match its 1970 predecessor, Tora! Tora! Tora! At the time that more focused account of “the day of infamy” was released, Japan was a firm ally in the Cold War and had yet to become America’s economic rival. While it was a big-budget box office bomb, Tora! Tora! Tora! presented the enemy with balance, though some diehard veterans grumbled about minor technical inaccuracies in a very historically detailed movie.

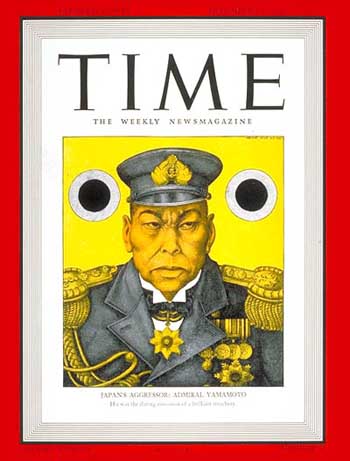

“Time” magazine's cover (December 22, 1941) depicted Japan's admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Combined Japanese Fleet and architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor, as a sinister Oriental mastermind in the Fu Manchu mold. Two weeks earlier, “Time's” December 8, 1941, issue, written before Pearl Harbor, had boasted that the American and British fleets were poised to spring on the Japanese should they snap under FDR's “war of nerves.”

Similar grumbling won’t affect Pearl Harbor’s fortunes. Screenwriter Randall Wallace simply did not write a historical documentary for enthusiasts to quibble over. While this PG-13 movie is about the Greatest Generation, it is not really for them. No need to let historical details get in the way when Pearl Harbor’s emotional kitsch is not even aimed at the men and women who actually experienced the war.

Two boys from Tennessee, played by Ben Affleck and Josh Hartnett, become Army aviators, and vie for the same serially monogamous Navy nurse, played by Kate Beckinsale. The characters are ultimately dull and forgettable: nearly every one of them could have been cast by MTV. Although Pearl Harbor’s makers loudly promised the movie would include strong female roles, its adorable nurses are looking for little more than pilot officers to marry. While this might have made a good vehicle for Elvis Presley, action-movie director Michael Bay (Armageddon) was clearly overmatched by Pearl Harbor’s triangulated love-dilemma: the awkward plot resolutions are implausible and unconvincing.

Pearl Harbor seeks to reinforce a vision of “America the Noble” by concocting a romantic story of historical convenience. Screenwriter Wallace’s initial take on Pearl Harbor came from a William Faulkner story about two brothers in bucolic Mississippi who hear about the Japanese attack on the radio, with the older one going away to enlist: nobody gets away with treating America like that! When we need an American response, a quintessentially pure-American response is what we’ll get.

The filmmakers want to show a new generation that Americans make stupid decisions as a people, but can be brave and worthy as individuals. It doesn’t take a seminar in revisionist history to know that for Hollywood, nothing could be more stupid than isolationism. When U.S. Army combat pilot Ben Affleck leaves to shoot down Germans for the RAF – during a Battle of Britain that takes place, in this movie, in 1941, a year after it actually occurred – a British commander asks the Yank why he is so awfully anxious to die: “Not anxious to die, sir; anxious to matter.” And Hollywood’s Americans so want to matter, fighting other countries’ wars, out of season!

We do get a little history. The Japanese actor Mako (Seven Years in Tibet) treats us to an uncanny period portrayal of Admiral Yamamoto, whose strike was brilliant but whose strategy was flawed. Overall, however, the Japanese are simply presented as stereotypical “nips,” who deliver almost every line in staccato Jap plainsong (not quite replete with spittle on the chin). Are they plotting a surprise attack, or a corporate takeover?

The movie’s efforts to provide historical context are predictably feeble: what’s this thing all about – oil or something? Fortunately, we don’t see enough of the enemy to really reconstitute any old venom. There is the usual Japanese spy (for once historically grounded), and even a duped Japanese-American dentist who gets an anonymous call at his office overlooking Pearl Harbor, asking humbly about the weather. But there is at least one Japanese-American good guy, a Hawaiian medic who confidently assists after the attack, and some Japanese pilots who wave Boy Scouts to take cover, an apparently true story.

There is one, rather incoherent, nod to popular revisionism (no revisionist thesis on the Second World War has received more support than the notion that the surprise attack was no surprise – to President Franklin Roosevelt and his advisers). Dan Aykroyd, of all people, plays a captain in naval intelligence able only to voice intuitive, equivocal warnings for the deaf ears around him in Washington – a character not far removed from the spooked clients he succored in Ghostbusters (“Who ya gonna call?”)

Against the defenders of Pearl and its associated bases, complete surprise was achieved – no mean accomplishment! The movie compromises with the pro- and anti-Admiral Kimmel factions by depicting the commander of the Pacific Fleet, like some imperial nabob, at the golf course that Sunday morning (he wasn’t), but hurrying back to take command.

In Pearl Harbor the Japanese attack seems to last for hours. In fact, the movie devotes 45 minutes to the two-pronged onslaught (in actuality, the first wave lasted 40 minutes, the second 36). Here, Disney’s bombs fall with their fuses winding, like deadly toys; torpedoes churn with agonizing slowness toward their targets (the preferred point of view is that of the ordnance). Mostly the Pearl Harbor battle lacks verisimilitude, and the soundtrack is overbearing. After the long, loud, and pious orchestral accompaniment, watching the attack is like listening to a Japanese motorcycle race while watching battle scenes from Star Wars. If you blink once or twice the looping Zeros, Kates, and Vals turn into Tie Fighters.

Cuba Gooding, Jr. reprises his now lukewarm role of a black guy struggling to be all he can be in a segregated navy. He plays real-life Dorie Miller, a cook and pugilist on the West Virginia who jumps onto a machine gun that he has never been trained to use and downs a Jap plane. In reality, the black sailor may not have gotten one, but it makes for a good story and Miller, who was killed later in the war, was awarded the Navy Cross for his service at Pearl Harbor. Gooding’s character is not developed, however: a callous waste of big box-office talent.

The aftermath, as U.S. capital ships list, burn, and capsize, is just a rip-off of Titanic, but without the empathy. Indeed, this reviewer saw not one wet eye in the house. In a feeble tribute to the female heroes, director Bay tries to convey the chaos in the hospital during and after the attack. But with a PG-13 rating, about all that can be done to horrify us is the surreal “shakycam” style of photography long since so trendy it seems more like a bad, if not satiric, music video. Beckinsale alone is resourceful, with nylon stockings for tourniquets and copious red lipstick to mark the foreheads of triage patients.

Meanwhile, our two flyboy heroes struggle into the air that Sunday morning, December 7, 1941, with Hawaiian shirts and hangovers to match, and manage to down seven Japanese planes between them, recreating the actual accomplishment of Lieutenants George S. Welch and Kenneth Taylor, but with fancy aerobatics that have rightly drawn scorn here and in Japan. What would the Tora! Tora! Tora! gadflies have made of them?

Jon Voight shines as FDR. The movie accurately shows a president very much in the minority in his desire to enter a world war, but who underestimates a despised enemy. After the Pearl Harbor attack Roosevelt promises payback for an angry nation. The military says it’s not possible, so the crippled commander-in-chief inspires them by struggling on his own to stand erect from his wheelchair. This would be absurdly out of character for the vain Mr. Roosevelt, but it certainly fits with the windy nature of our movie.

Our two fighter jocks, Affleck and Hartnett, are implausibly assigned to fly B-25 bombers for a little thirty-second public relations stunt over Tokyo on April 18, 1942, led by Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, played convincingly but with camp by Alec Baldwin. Showing atomic bombings would spoil the schmaltzy kind of payback that our movie promises – but by now we hardly care to wait for it any longer. Thus Doolittle’s raid seems almost the start of a second movie – but while it would have been a very interesting one, it must receive short shrift. The Doolittle raiders’ crash-landing in China merely serves to tie up the loose ends of Pearl Harbor’s icky love triangle, with a Christlike sacrifice to boot, but no real surprise, and not much impact.

From Pearl Harbor you will likely leave unmoved after three hours of flag-waving. And if you knew nothing beforehand about the complex political dynamics that would in 1941 lead an aspiring Japanese superpower – undefeated on the battlefield, but nevertheless stuck in a Chinese quagmire not unlike our own Vietnam – brutally to awaken a military giant such as the United States, you will leave this movie none the wiser. In our modern era of button-pushing diplomacy, where cruise missiles are launched as the public opinion polls waver, this is not good history at all.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 20, no. 3 (May/June 2001), pp. 45-47

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a