Missing Passages of “A Year in Treblinka”

Censorship? Plagiarism?

This paper utilizes developing technology to produce a new English translation of Jankiel Wiernik’s A Year in Treblinka and critically compares it to the 1979 English translation published by Alexander Donat. It particularly focuses on the passages that Donat selectively omitted. By comparing the texts, it highlights discrepancies and explores the implications of these alterations. It also discusses Donat’s apparent plagiarism of the first English edition. Furthermore, the paper situates Donat’s work within a larger discourse on uncredited source plagiarism among Holocaust historians, illustrating a concerning trend of misattributed sources and lack of transparency in historical documentation. Ultimately, this research calls for a reevaluation of the narratives that have shaped our understanding of Holocaust testimonies, emphasizing the benefit of fidelity to original accounts. For the first time in English, rediscover the passages that Donat didn’t want you to read.

A Year in Treblinka is one of the first and most important eyewitness accounts of the Treblinka “death camp.” This short book is attributed to Jankiel Wiernik, with at least three English translations appearing since 1944.[1] However, all of these translations are largely based on the edition published by the American Representation of the General Jewish Workers’ Union of Poland (hereafter “first English edition”).[2] The most widely-cited translation is from Alexander Donat’s anthology The Death Camp Treblinka: A Documentary, published in 1979.

Due to the scarcity of the Polish version, of which only 2,000 copies were reportedly printed, these English translations have been the most accessible versions of the book. However, no English translator has pointed out that there are numerous missing and altered passages from the original Polish. With several copies of the Polish Rok w Treblince (A Year in Treblinka) now available online, access has never been easier to view the original. Using relatively recent text extraction and translation technology, we compare Donat’s translation to a new AI-assisted English translation of the Polish text, with a few remarks about the first English edition.

Method

The text from scanned pages of the Polish Rok w Treblince were extracted with a digital tool. The extracted text included all Polish diacritical marks. The full extraction was then proofread and corrected.

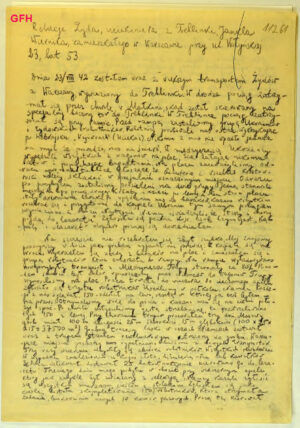

Three published copies of Rok w Treblince were consulted, as well as the pre-publication typescript:

- Primary copy: Center for Jewish History, Identifier RG 1436.

- Second copy: Ghetto Fighters House Archives, Registry No. 11261collec, pp. 1-13.

- Third copy: Center for Jewish History, Identifier: RG 720.

- Typescript: Ghetto Fighters House Archives, Registry No. 11261collec, pp. 14-35.

Due to the age and condition of the primary copy that was used, the extraction contained various defects, including corrupted or missing words and formatting errors. All of the published copies were used to identify and correct these. In instances where typos are present in the published version, the typescript was consulted to identify the original intent of the author. Missing and unclear punctuation were also examined and corrected.

After this process was completed, the entire Polish transcript was AI translated. This translation was also proofread and corrected, comparing with both the Polish versions and the English translations. Further corrections to the Polish versions and AI-assisted translation were made in consultation with the various copies, other translation software, and a Polish-English dictionary.[3]

The AI translation was placed in a document with the first English edition and the Donat translation, with the three translations arranged in parallel columns for easier comparison. Because the original Polish version does not include as many paragraph breaks or any chapter headings, it was broken up, so the flow matched the Donat and first English editions, which are nearly identical in this regard.

The entire AI translation was proofread again, comparing it to the two English translations, and additional corrections were made in consultation with the Polish documents. The final result is posted at the end of this paper.

General Remarks on the English Translations

The first English edition is missing many passages from the Polish, although they are included in the handwritten draft translation. While this could be “self-censorship,” it is more likely due to the constraints of publishing the work in a small booklet with a page limitation. There are also a sizable number of typos, further indicating it may have been rushed for publication. The first English edition breaks up the Polish text in more paragraphs, and adds chapter headings.

Many of the omitted passages are restored by Donat in his translation in The Death Camp Treblinka. However, Donat’s translation does not need to be compared closely to the first English edition because of how similar they are. Donat was not the original translator for the American Representation of the General Jewish Workers’ Union of Poland, but the version published in his book is so close as to constitute plagiarism. The sentence structure is nearly identical, and many passages are word-for-word matches. The paragraph breaks are nearly identical throughout, and he reproduces chapter headings in the exact same place (other than one missing chapter heading). These cannot be explained by reference to the Polish, because the sentence structure between the Polish and English vary significantly in places, in addition to having fewer paragraphs and no chapters.

An example from the first chapter shows how close the translations are. Page numbers are indicated in parentheses.

| First English (5) | Donat (148) |

|---|---|

| Today I am a homeless old man without a roof over my head, without a family, without any next of kin. I talk to myself. I answer my own questions. I am a nomad. It is with a sense of fear that I pass through human settlements. | Today I am a homeless old man without a roof over my head, without a family, without any next of kin. I keep talking to myself. I answer my own questions. I am a nomad. It is with a sense of fear that I pass through places of human habitation. |

This similarity persists throughout Donat’s work. A couple additional examples are presented to illustrate this. The first from Chapter VIII/Chapter IX:[4]

| First English (27) | Donat (169) |

|---|---|

| We began to suffer greatly from the cold and they started issuing blankets to us. In my absence from Camp No. 2, a carpentry shop had been installed. A baker from Warsaw functioned as its foreman. | We began to suffer greatly from the cold and they started issuing blankets to us. While I had been away from Camp No. 2, a carpentry shop had been installed there. A baker from Warsaw served as its foreman. |

Finally, an example from Chapter XII:

| First English (40) | Donat (182) |

|---|---|

| I continued working in Camp No. 1, returning to Camp No. 2 for the night. I was constructing an enclosure of birchwood a low fence around the flower garden where animals and birds were also kept. It was a quiet, pretty spot. Wooden benches were scattered around for the convenience of the Germans and Ukrainians. But, alas, that serene spot was the seat of infamous plotting, the only topic of which undoubtedly was how to torture us, the helpless wretches. | I continued working at Camp No. 1, returning to Camp No. 2 each night. I was constructing a Birchwood enclosure, a low fence around the flower garden where domesticated animals and birds were also kept. It was a quiet, pretty spot. Wooden benches had been placed there for the convenience of the Germans and Ukrainians. But alas, that serene spot was the seat of infamous plotting, the only theme of which undoubtedly was how to torture us, the hopeless wretches. |

Due to the fact that Donat’s translation is more complete and due to its near-identical similarity to the first English edition, we will only be comparing the new AI-assisted translation to Donat.

Passages Missing from Donat’s Version

For the analysis below, complete paragraphs are reproduced from Donat to provide the full context, and to make identifying the passages easier. This way, the omitted passages can be placed into their proper context, and a fair comparison can be made between the translations. Page number references are included in parentheses.

Passages left out by Donat are highlighted with a yellow background. These are all the passages we identified that have been completely left out of Donat’s translation. There are also several passages where the meaning was altered, most of which are not included here. In many of these cases, the alteration was not material to the overall sense of the paragraph or book.

Chapter II

| AI Translation | Donat (149) |

|---|---|

| On the street, the “Scharführer” was lining everyone up in ranks. They were gathered without distinction of gender or age. The “Scharführer” performed his work with passion. His face beamed with a smile. Slim and supple, he bustled everywhere. He watched us, sorted us. His gaze swept over everyone. With a sadistic smile, he looked at the great work of his great homeland, which in one fell swoop will tear off the head of the harmful hydra. My gaze falls on his face. | In the street one of the leaders arranged the people in ranks, without any distinction as to age or sex, performing his task with glee, a satisfied smile on his face. Agile and quick of movement, he was here, there and everywhere. He looked us over appraisingly, his eyes darting up and down the ranks. With a sadistic sneer he contemplated the great accomplishment of his mighty Fatherland which, at one stroke, would chop off the head of the loathsome serpent. |

While Donat’s translation of “He looked us over appraisingly” could be argued as roughly accurate, it fails to convey the more active sense of the “sorting.” It scarcely needs to be pointed out that any mention of “sorting” or “selection” by the Germans is noteworthy. The original Polish sentence is “Oglądał nas, sortował.”

| AI Translation | Donat (150) |

|---|---|

| Amidst boundless torment, we reached Małkinia. We stood there all night. Ukrainians boarded the wagon and demanded valuables. Everyone gave to save their lives for a short time. Unfortunately, I had nothing. Firstly, I had left home unexpectedly, and secondly, I had sold everything during the war to stay afloat because I wasn’t earning any money. In the morning, the train departed and we arrived at Treblinka station. I noticed a train passing by, carrying ragged, half-naked, starving people. They spoke to us, but we couldn’t understand them. | Amidst untold agonies, we finally reached Malkinia, where our train stopped for the night. Ukrainian guards came into our car and demanded our valuables. Everyone who had any surrendered them just to gain a little longer lease on life. Unfortunately, I had nothing of value because I had left my home unexpectedly and because I had been unemployed and had gradually sold all my possessions in order to keep going. The next morning our train started to move again. We saw a train passing by filled with tattered, half-naked, starved people. They were trying to say something to us, but we could not understand what they were saying. |

Donat leaves out the information that the train had traveled south from Małkinia to the Treblinka train station where the author witnesses the train of people passing. By leaving out this passage, Donat creates geographical confusion, implying this happened further north, possibly when the train was still at or near Małkinia. If Wiernik[5] witnessed a train full of half-naked people traveling north, a likely scenario is that they were leaving the Treblinka area after surviving the “bathhouses.” The implication is that he may be responsible for identifying several thousand hitherto-unknown survivors of this “death camp,” of which it is generally assumed fewer than 100 people survived, most of them escaping during the inmate uprising of August 2, 1943. Coincidentally, if Wiernik ever wondered “where did they go?” about that train full of people, he would be considered a proto-Holocaust revisionist.

Chapter IV

| AI Translation | Donat (154-155) |

|---|---|

| We were led into the forest and ordered to dismantle barbed wire barriers and cut down trees. Kostenko and Andreyev were very gentle. They ignored our work. Nikolay, on the other hand, urged us on with a whip and shouted. Among all the chosen ones, there were no true professionals, but since they didn’t want to work with corpses, they posed as carpenters. These were ridiculed and given unstinting beatings. | We were marched to the woods and were ordered to dismantle the barbed wire fences and cut timber. Kostenko and Andreyev were very gentle. Nikolay, however, used the whip freely. Truth to tell, there were no real specialists among those who had been picked for the construction gang. They had simply reported as “carpenters” because they did not want to be put to work handling corpses. They were continuously whipped and humiliated |

| AI Translation | Donat (155) |

|---|---|

| That day, we were again surrounded by Germans. And there were about 700 people. Among the Germans, Franz and his dog. Suddenly, he asked with a smile: “Who knows German?” About 50 people stepped forward. He ordered them to step out of line and form separate groups. He did all this with a smile. This so that he could not be suspected of anything. They were kidnapped and never returned to us. They were not on the list of the living either. Among what torment and torture they died, no pen can describe. We survived again at this job and in the same conditions for a few days. I worked together with one colleague the whole time, and strangely, fate spared us. Perhaps because we were both professionals, or perhaps because we were destined to see the torments and corpses of so many of our brothers. They gave me and my colleague boxes for lime. Andreyev guarded us. My friend was a good craftsman and also listened to my advice. The “watchman” liked the work. He showed us much kindness. He even brought us a piece of bread each. This was a great thing for us. We were dying of hunger. People, saving themselves from another death, which I will describe, were creaking with hunger, turning yellow, and collapsing. Our work group grew larger. New workers arrived. They began digging the foundation for a building. What this building was supposed to be, none of us knew. In the yard stood a single wooden building, surrounded on all sides by a high fence. Its purpose was a mystery to everyone. | On that particular day there were many Germans around, and we were about 700. Franz was there, too, with his dog. All of a sudden he asked, with a smile on his face, whether any of us knew German. Approximately 50 men stepped forward. He ordered them all out and form a separate group, smiling all the while to allay our suspicions. The men who admitted knowing German were taken away and never came back. Their names did not appear on the list of survivors and no pen will ever be able to describe the tortures under which they died. Again, a few days went by. We worked at the same assignment and lived under the same conditions. All this time I was working with one of my colleagues and fate was strangely kind to us. Perhaps it was because we were both specialists in our trade, or because we had been destined to witness the sufferings of our brethren, to look at their tortured corpses, and to live to tell the tale. Our bosses gave me and my colleague boxes for lime. Andreyev supervised us. Our guard considered our work satisfactory. He showed us considerable kindness and even gave each one of us a piece of bread, which was quite a treat since we were practically starving to death. Some people who had been spared from another form of death, which I shall discuss later on, would become yellow and swollen from hunger and finally drop dead. Our group of workers grew; additional workers arrived. The foundations were dug for some sort of building. No one knew what kind of a building this would be. There was in the courtyard one wooden building surrounded by a tall fence. The function of this building was a secret. |

Chapter V

| AI Translation | Donat (156) |

|---|---|

| The Treblinka camp was divided into two parts. Camp No. 1 had a railway siding and a ramp for unloading live transports. There was also a large square where the belongings of those arriving were stored. Foreign Jews brought the most with them. There was also a field hospital (“lazaret”) there, 30x6×21 meters long, where two men worked. They wore white aprons and red crosses on their shoulders. They were considered doctors. They selected the elderly and sick from the transports and seated them on a long bench, facing the grave. Germans and Ukrainians stood behind them. They shot the victim in the neck. The corpse fell directly into the grave. When a large number of corpses had accumulated, they were gathered and set on fire. They burned with living flames. | Camp Treblinka was divided into two sections. In Camp No. 1 there was a railroad siding and a platform for unloading the human cargo, and also a wide open space, where the baggage of the new arrivals was piled up. Jews from foreign countries brought considerable luggage with them. Camp No. 1 also contained what was called the lazaret (infirmary), a long building measuring 30 x 2 meters. Two men were working there. They wore white aprons and had red crosses on their sleeves; they posed as doctors. They selected from the transports the elderly and the ill, and made them sit on a long bench facing an open ditch. Behind the bench, Germans and Ukrainians were lined up and they shot the victims in the neck. The corpses toppled right into the ditch. After a number of corpses had accumulated, they were piled up and set on fire. |

Donat leaves out the extra measurement of the “lazaret,” as well as the more evocative phrasing at the end of the paragraph. Donat consistently omits such poetic language.

| AI Translation | Donat (157) |

|---|---|

| Camp No. 2 was completely different. It had a 30×10 meter workers’ barracks, a laundry, a small laboratory, quarters for 17 women, a guardhouse, and a well. In addition, there were 13 gas chambers for the victims, which I will describe in detail. Around these buildings was a barbed-wire fence. Behind the fence was a 3×3-meter ditch. Beyond the ditch was a second barbed-wire fence. Both fences reached a height of three meters. Between these fences was a steel-wire barbed wire fence. Ukrainians stood guard all around. The entire camp was surrounded by a four-meter-high barbed-wire fence. The fence was decorated with fir trees. The square had four four-story observation towers and six single-story observation towers. | Camp No. 2 was entirely different. It contained a barrack for the workers, 30 x 10 meters, a laundry, a small laboratory, quarters for 17 women, a guard station and a well. In addition there were 13 chambers in which inmates were gassed. All of these buildings were surrounded by a barbed wire fence. Beyond this enclosure, there was a ditch of 3 x 3 meters and, along the outer rim of the ditch, another barbed wire fence. Both of these enclosures were about 3 meters high, and there were steel wire entanglements between them. Ukrainians stood on guard along the wire enclosure. The entire camp (Camps 1 and 2) was surrounded by a barbed wire fence 4 meters high, camouflaged by saplings. Four watchtowers stood in the camp yard, each of them four stories high; there were also six one-storied observation towers. |

Here, Donat redacts Wiernik’s promise to describe the gas chambers in detail.

| AI Translation | Donat (157-158) |

|---|---|

| The doors of each room on the side of Camp No. 2 (2.50 x 1.80) opened only outward from the bottom upwards using iron supports and were closed with iron hooks placed on the doorframes and wooden latches. Victims were admitted through the door on the corridor side. The door on the side of Camp No. 2 was used to remove gassed corpses. Along the chamber was a power plant, almost the same size as the chambers, but higher by the difference in the height of the ramp. This power plant supplied electricity to the first and second camps. In the power plant stood an engine from a Soviet tank, used to pump gas into the chambers. The gas was introduced by connecting the engine to the intake pipes. The speed of the victims’ death depended on the amount of exhaust gas introduced. | Each chamber had a door facing Camp No. 2 (1.80 by 2.50 meters), which could be opened only from the outside by lifting it with iron supports and was closed by iron hooks set into the sash frames, and by wooden bolts. The victims were led into the chambers through the doors leading from the corridor, while the remains of the gassed victims were dragged out through the doors facing Camp No. 2. The power plant operated alongside these chambers, supplying Camps 1 and 2 with electric current. A motor taken from a dismantled Soviet tank stood in the power plant. This motor was used to pump the gas, which was let into the chambers by connecting the motor with the inflow pipes. The speed with which death overcame the helpless victims depended on the quantity of combustion gas admitted into the chamber at one time. |

| AI Translation | Donat (158-159) |

|---|---|

| Between 450 and 500 people were let into the 25-square-meter chamber. It was terribly cramped. They stood side by side. Children were carried in, thinking they would avoid extermination. On the way to their deaths, they were beaten and pushed with rifle butts and gas pipes. Dogs were set on them. The dogs barked, bit, and lunged at their victims. So, screaming, trying to avoid the blows and the dogs, everyone threw themselves into the embrace of death and ran into the chamber. The stronger ones pushed the weaker ones. The noise lasted only a short time. The door slammed shut. The chamber was full. They turned on the engine and connected it to the intake pipes. In 25 minutes at most, everyone was lying in a row. They didn’t even lie down, because there was nowhere else to lie. They simply fell into each other’s arms and stood. | Between 450 and 500 persons were crowded into a chamber measuring 25 square meters. Parents carried their children in their arms in the vain hope that this would save their children from death. On the way to their doom, they were pushed and beaten with rifle butts and with Ivan’s gas pipe. Dogs were set upon them, barking, biting and tearing at them. To escape the blows and the dogs, the crowd rushed to its death, pushing into the chamber, the stronger ones shoving the weaker ones ahead of them. The bedlam lasted only a short while, for soon the doors were slammed shut. The chamber was filled, the motor turned on and connected with the inflow pipes and, within 25 minutes at the most, all lay stretched out dead or, to be more accurate, were standing up dead. Since there was not an inch of free space, they just leaned against each other. |

In Chapter VII, Donat’s translation states, “As I have already indicated, there was not much space in the gas chambers.” However, the above is the previous indication of the cramped nature of the chambers, a passage Donat omits for no good reason.

| AI Translation | Donat (159) |

|---|---|

| Ten to twelve thousand people were gassed daily. We constructed a narrow track and transported people to their graves on a platform. But it was impossible to keep up, so two men were dragged on belts. That evening, I experienced another difficult moment. | Between ten and twelve thousand people were gassed each day. We built a narrow-gauge track and drove the corpses to the ditches on the rolling platform. |

Here, Donat omits the inconvenient fact that the narrow-gauge rail transportation the crew built in response to the large number of corpses was so poorly planned that they had recourse to dragging corpses by hand.

| AI Translation | Donat (160) |

|---|---|

| At the entrance to Camp No. 2 are single-story observation towers. The towers were accessed by ladders. The victims were tortured by these ladders. Their legs were placed between the rungs, and the capo held their heads down so that the victim could not move. He vented his rage on the unfortunate, inflicting severe blows. Among the least severe scourges were 25 lashes. I saw it for the first time in the evening. The moon and searchlights illuminated the horrific massacre of the half-dead and the corpses lying beside them. The groans of the tortured mingled with the whistling of the lashes as they fell on their backs. | A one-storied watchtower stood at the entrance of Camp No. 2. It was ascended by means of ladders, and these ladders were used to torture some of the victims. Legs were placed between the rungs and the overseer held the victim’s head down in such a way that the poor devil couldn’t move while he was beaten savagely, the minimum punishment being 25 lashes. I saw that scene for the first time in the evening. The moon and the reflector lights shed an eerie light upon that appalling massacre of the living, as well as upon the corpses that were strewn all over the place. The moans of the tortured mingling with the swishing of the whips made an infernal noise. |

Chapter VII

| AI Translation | Donat (162-163) |

|---|---|

| During my time working in Camp No. 1, I saw everything: how our brothers were led to the gas chambers and the terrible trials they endured before their deaths. This was the period when the transports arrived. When the train arrived, women and children were immediately herded into the barracks. Men were left in the yard. Women and children were ordered to undress. Naive women took out towels and soap, hoping they would bathe. The torturers demanded order and tidiness, beating and torturing. Children cried. Adults moaned and screamed. Nothing helped; the whip was stronger. It weakened some, and revived others. After everything was sorted, the women and girls entered the barracks. | While I was working in Camp No. 1 many transports arrived. Each time a new transport came, the women and children were herded into the barracks at once, while the men were kept in the yard. The men were ordered to undress, while the women, naively anticipating a chance to take a shower, unpacked towels and soap. The brutal guards, however, shouted orders for quiet, and kicked and dealt out blows. The children cried, while the grownups moaned and screamed. This made things even worse; the whipping only became more cruel. |

Here, Donat removes more evocative phrasing from the original. The conventional biography of Wiernik is that he was unused to writing and had to be persuaded to pick up a pen and write his account of Treblinka. Of course, we now know that Wiernik had experience writing and copying communist propaganda as far back as 1935.[6]

There is also a contradiction in that the women and children were “immediately” herded into the barracks earlier in the paragraph, but only “after everything was sorted” later in the paragraph. Donat unilaterally decides which one is correct and omits the contradictory account.

Wiernik does not explain how some of the victims being whipped, beaten and tortured could have been “revived” by this, and Donat wisely leaves out this strange observation. The original Polish sentence is “Usłabia jednych, cuci drugich.”

| AI Translation | Donat (164) |

|---|---|

| Victims were often let into the chambers all night long, without the motor running. The cramped conditions and suffocation took their toll, killing a larger percentage amidst the terrible torture. But many remained alive, mostly children, resistant. These survived after being thrown from the chambers. But all were finished off by a German revolver. The worst part was standing naked in the biting cold, awaiting their turn for a cruel death. However, the gas chambers were no less horrific. | Often people were kept in the gas chambers overnight with the motor not turned on at all. Overcrowding and lack of air killed many of them in a very painful way. However, many survived the ordeal of such nights; particularly the children showed a remarkable degree of resistance. They were still alive when they were dragged out of the chambers in the morning, but revolvers used by the Germans made short work of them… |

It almost makes one wonder why the Germans constructed non-lethal, survivable gas chambers when “standing naked in the biting cold” was no less horrific. By contrast, there is no wonder why Donat omits this snippet of atrocity propaganda.

| AI Translation | Donat (164) |

|---|---|

| The executioners welcomed the foreign transports with genuine joy: apparently, they reacted to these deportations there. So as not to arouse suspicion about what they were doing to the unfortunates, they were transported on passenger trains, and allowed to take everything they needed with them. These people arrived elegantly dressed. They brought with them loads of food and clothing. The train had attendants and even a dining car. They carried plenty of fat, coffee, tea, and so on. But the stark reality suddenly appeared before them. They were pulled from the cars, and everything proceeded in the same manner as I have already described. The next day, there was no trace of them. All that remained were clothes, food, and labor—the hard work of burying the corpses. | The German fiends were particularly pleased when transports of victims from foreign countries arrived. Such deportations probably caused great indignation abroad. Lest suspicion arise about what was in store for the deportees, these victims from abroad were transported in passenger trains and permitted to take along whatever they needed. These people were well dressed and brought considerable amounts of food and wearing apparel with them. During the journey they had service and even a dining car in the trains. But on their arrival in Treblinka they were faced with stark reality. They were dragged from the trains and subjected to the same procedure as that described above. The next day they had vanished from the scene; all that remained of them was their clothing, their food supplies, and the macabre task of burying them. |

| AI Translation | Donat (164) |

|---|---|

| The number of transports increased with each passing day, as there were now 13 gas chambers. Sometimes up to 20,000 were gassed daily. All we could hear were screams, cries, and moans. People remained at work and, for now, alive; on the days the transports arrived, they didn’t eat and cried constantly. The weaker and more sensitive suffered nervous breakdowns and committed suicide, mostly among the intelligentsia. Those who did so, when they returned to the barracks after working with the corpses, their ears still full of the screams and moans of the victims – they hanged themselves at night. There were at least 15 to 20 such incidents a day. | The number of transports grew daily, and there were periods when as many as 30,000 people were gassed in one day, with all 13 gas chambers in operation. All we heard was shouts, cries and moans. Those who were left alive to do the work around the camps could neither eat nor control their tears on days when these transports arrived. The less resistant among us, especially the more intelligent, suffered nervous breakdowns and hanged themselves when they returned to the barracks at night after having handled the corpses all day, their ears still ringing with the cries and moans of the victims. Such suicides occurred at the rate of 15 to 20 a day. |

There is no omission here, but Donat inflates the original 20,000 gassed per day to 30,000.

Chapter VIII

| AI Translation | Donat (165-166) |

|---|---|

| There were frequent reactions. I will describe one such incident. One of the girls stepped out of line. Naked, she jumped over a three-meter-high barbed wire fence and began to run towards us. The Ukrainians noticed this and gave chase. The first one gave chase, but because he was too close, he couldn’t shoot. She snatched his rifle. It was difficult for them to shoot at all, as there were guards all around, making it easy to injure someone. But their blood ran cold. A shot was fired, killing a Ukrainian, and in her fury, she struggled with the others. A second shot was fired, wounding another Ukrainian, ripping off his arm (after healing, he remained in our camp and was there until the last moment). Finally, they caught her. She paid dearly for all this. She was beaten, bruised, spat on, kicked, and then killed. This is our nameless heroine. | On one occasion a girl fell out of line. Nude as she was, she leaped over a barbed wire fence three meters high, and tried to escape in our direction. The Ukrainians noticed this and started to pursue her. One of them almost reached her but he was too close to her to shoot, and she wrenched the rifle from his hands. It wasn’t easy to open fire since there were guards all around and there was the danger that one of the guards might be hit. But as the girl held the gun, it went off and killed one of the Ukrainians. The Ukrainians were furious. In her fury, the girl struggled with his comrades. She managed to fire another shot, which hit another Ukrainian, whose arm subsequently had to be amputated. At last they seized her. She paid dearly for her courage. She was beaten, bruised, spat upon, kicked and finally killed. She was our nameless heroine. |

Donat’s translation suggests that the nude woman’s act of defiance was an outlier, whose defiance turned her into a hero. In the original, though, Wiernik states that it is just one example of the “frequent” attempts at escape or resistance. Wiernik does not describe how many people were included in the Treblinka pantheon of nameless heroes.

Donat also removes the passage implying that the medical facilities at the “death camp” were sufficient for the treatment and long-term recovery of an amputee.

| AI Translation | Donat (167) |

|---|---|

| Secondly, one event knocked them out of grace and into the arms of death. Among them were goldsmiths, sorting precious metals. And there were countless of them. Full crates. A separate barracks was assigned to sorting and stacking. There was no special guard. They gained each other’s trust. Where would they take them? Even if they had appropriated anything, it too would eventually become German property. | Among these men there were jewelers who appraised the articles of precious metal which the deportees had brought with them. There was quite a lot of this. The sorting and classifying was done in a separate barrack to which no special guard had been assigned, for there was no reason to expect that these men would be able to steal any of the loot. Where would they dispose of their pilferings? Eventually, whatever they might manage to steal would only get back to the Germans again. |

Wiernik’s book suggests that the jewelers were to be freed from Treblinka when the camp’s purpose had ended. Donat removes the passage highlighting that the deciding factor in the decision to kill them was the Ukrainian guards’ lust for gold.

| AI Translation | Donat (167) |

|---|---|

| When they noticed that the Jews were working with gold almost unchecked, they began to force them to steal. The Jews were forced to steal diamonds and gold and turn them over. If they hadn’t, they would have been killed by them. Day after day, a gang of Ukrainians carried off valuables from the treasury. A German noticed this, and naturally, the Jews were punished. They were searched, and gold and other valuables were found. They couldn’t confess that they were doing this under pressure, because it would have been of little use anyway. The torture began. The golden dream of freedom for the caged bird was over. They were now worse off than the other workers. Naturally, after this incident, only half of them remained. There had been 150 of them before. Those who survived suffered hunger and misery. And their suffering was no ordinary one either. | When the Ukrainians noticed that the Jews were handling the gold under practically no control, they began coercing them to steal. The Jews were compelled to deliver diamonds and gold to the Ukrainian guards or else be killed. Day after day, a gang of Ukrainians took valuables from the room where the valuables of the deportees were kept. One of the Germans noticed this and of course it was the Jews who had to pay the penalty. They were searched, and the search disclosed gold and precious stones on their persons. They could not claim that they had stolen these articles under duress; the Germans would not have believed their story. They were tortured and now they were worse off than the camp laborers. Only half of them- there had been 150 of them were left alive. Those who survived suffered starvation, misery and incredible tortures. |

This is yet another flowery passage from an author who supposedly needed help and encouragement from his friends to write this book. It also follows from the previous reference to the jewelers expecting to be freed from the camp once it closed.

| AI Translation | Donat (167) |

|---|---|

| The entire square was strewn with piles of various items. It’s understandable that millions of people left behind millions of different clothes, underwear, and so on. Everyone believed they were going to be mistreated, but not to die, so they took with them the best, the most necessary things. The backpacks were full, the suitcases and sacks were full. The food was exquisite. Whatever your heart desired was in the square in Treblinka. All in huge quantities. As I passed, I noticed a full pile of fountain pens, real coffee, tea, and so on. The camp yard was strewn with candy. Foreign transports brought in a lot of fat. These people truly believed they would continue to live. | The entire yard was littered with a variety of articles, for all these people left behind millions of items of wearing apparel and so forth. Since they had all assumed that they were merely going to be resettled at an unknown place and not sent to their death, they had taken their best and most essential possessions with them. The camp yard in Treblinka was filled with everything one’s heart might desire. There was everything in plenty. As I passed, I saw a profusion of fountain pens and real tea and coffee. The ground was literally strewn with candy. Transports of people from abroad had come well supplied with fats. All the deportees had been fully confident that they were going to survive. |

Chapter IX

In Donat’s book, the heading for Chapter IX is entirely missing. He skips from VIII (p. 165) straight to X (p. 173). So in this case, we follow the first English edition’s Chapter IX, although the actual text can be found in Chapter VIII of Donat’s book.

| AI Translation | Donat (169) |

|---|---|

| The “Hauptsturmführer” and both commandants ordered me to build a laundry, a laboratory, and quarters for 15 women. These buildings were to be constructed of old materials. Jewish buildings were being demolished nearby. I recognized this from the house numbers. I selected workers and began working. I brought some of the raw timber from the forest. Time at work flew by. Day after day, it slipped away. The sight of everything became commonplace. I became indifferent. | The Hauptsturmführer and the two commandants ordered me to build a laundry, a laboratory and accommodations for 15 women. All of these structures were to be built from old materials. Jewish-owned buildings in the vicinity were being dismantled at the time. I could tell them by their house numbers. I selected my crew and began to work. I brought in some of the new lumber from the woods myself. Time flew fast on the job. |

This is another example of Wiernik’s self-reflection, utilizing poetic language to psychoanalyze his mental state over time. It is omitted by Donat.

| AI Translation | Donat (170) |

|---|---|

| An attempt to burn the corpses began, but it failed. It turned out that women burned better than men. So, women were used as kindling. Since it was hard work, competition began between groups – Who would burn more? Records were kept, and the number of those burned was recorded daily. Despite this, the results were very poor. They poured gasoline on the corpses, and burned them that way. It cost too much, and the results were poor. The men almost refused to burn themselves. When a plane was spotted in the air, work stopped, and the pulled-out corpses were covered with Christmas trees to avoid being noticed from the air. | Work was begun to cremate the dead. It turned out that bodies of women burned more easily than those of men. Accordingly, the bodies of women were used for kindling the fires. Since cremation was hard work, rivalry set in between the labor details as to which of them would be able to cremate the largest number of bodies. Bulletin boards were rigged up and daily scores were recorded. Nevertheless, the results were very poor. The corpses were soaked in gasoline. This entailed considerable expense and the results were inadequate; the male corpses simply would not burn. Whenever an airplane was sighted overhead, all work was stopped, the corpses were covered with foliage as camouflage against aerial observation. |

Although it is clear from the text that this first attempt at open-air cremations failed, the Polish makes it explicit. Both works indicate that “the results were poor” later in the same paragraph.

The Polish text uses the word “choinkami” several times to refer to the type of trees used around the camp, which is the Polish word for “Christmas trees,” although it could also refer to a fir or spruce. The English translations use “foliage” or “saplings.”

| AI Translation | Donat (170) |

|---|---|

| Then, one day, an Oberscharführer with an SS insignia arrived at the camp and ordered a veritable hell. He was a man of about 45, average height, always smiling. His favorite word – “tadellos” So that’s how he got the nickname “tadellos.” His rather gentle face didn’t express what was hidden in his vile soul. He found true satisfaction in this as he watched the burning corpses. This flame was the most precious thing to him. He caressed it with his eyes, lay beside it, and smiled. He spoke to it. | Then, one day, an Oberscharführer wearing an SS badge arrived at the camp and introduced a veritable inferno. He was about 45 years old, of medium height, with a perpetual smile on his face. His favorite word was “tadellos [perfect]” and that is how he got the by-name Tadellos. His face looked kind and did not show the depraved soul behind it. He got pure pleasure watching the corpses burn; the sight of the flames licking at the bodies was precious to him, and he would literally caress the scene with his eyes. |

Donat tones down Tadellos’s insane pyromania to a simple sadistic glee as he revels in the fire of the burning corpses. Tadellos lounging next to these pyres also contradicts the later comparison of them to volcanoes, spewing fire and lava, too dangerous to approach.

| AI Translation | Donat (171) |

|---|---|

| The burning of the corpses was a resounding success. Because the Germans were pressed for time, they began building new grates, increasing the number of corpses, and burning 10,000 to 12,000 corpses at a time. A veritable inferno ensued. Looking at it from a distance, it looked as if a volcano had erupted, lifting the earth’s crust, and spewing fire and lava. It hissed, sputtered, and crackled all around. Up close, the smoke, fire, and heat were unbearable. This went on for quite a while. There were approximately 3.5 million corpses. | The cremation of the corpses proved an unqualified success. Because they were in a hurry, the Germans built additional fire grates and augmented the crews serving them, so that from 10,000 to 12,000 corpses were cremated at one time. The result was one huge inferno, which from the distance looked like a volcano breaking through the earth’s crust to belch forth fire and lava. The pyres sizzled and crackled. The smoke and heat made it impossible to remain close by. It lasted a long time because there were more than half a million dead to dispose of. |

Previously, Donat had inflated 20,000 gassing victims per day to 30,000. In this case, he does the opposite, reducing 3.5 million total corpses to “more than half a million.” Three to 3.5 million were the most common estimates attributed to the witnesses interrogated during the 1944 Soviet investigation of Treblinka, where the Red Army had already translated Wiernik’s book before starting interrogations. By 1979, when Donat published his book, the 3.5 million death toll for Treblinka had been significantly reduced.

Chapter X

| AI Translation | Donat |

|---|---|

| I have worked through the winter, seen the suffering and death of millions, and have already lived to see the first warm rays of the sun. |

This passage is entirely missing from both the first English edition and Donat’s translation. It is possibly the most flowery passage in the entire work. It should be placed between the bottom of page 173 and the top of page 174 of The Death Camp Treblinka. In the Polish original, this sentence appears as its own paragraph.

| AI Translation | Donat (174) |

|---|---|

| It was April 1943. Transports from Warsaw began arriving. We were told that 600 people from Warsaw remained working in Camp No. 1, which turned out to be true. Typhus was rampant in the first camp at the time. Those who were ill were killed. Three women and one man arrived from the Warsaw transport. This man was the husband of one of the women. They treated these Warsaw transports particularly harshly. Even more so over women than over men. Women and children were selected, brought to the fire, and when the robbers had had their fill of the terrified women and children, they would kill them at the stake and burn them. Such frolics with women and children from these transports were commonplace. Women would faint and be dragged almost dead. In panic, children would throw themselves into their mothers’ arms. Women begged for mercy, closing their eyes in fear, forgetting for a moment where they were. The robbers would contort their faces with satisfaction and hold their victims in suspense for a long, long time. While they were killing some women and children, others were already standing, waiting their turn. More than once, the executioners would tear a crying child from its mother’s arms and throw it alive into the fire. They would laugh. At the same time, they urged mothers to heroically jump into the fire after their children, and mocked their cowardice. I experienced thousands of such terrible, horrifying images. | In April, 1943, transports began to come in from Warsaw. We were told that 600 men in Warsaw were working in Camp No. 1; this report turned out to be based on fact. At the time a typhus epidemic was raging in Camp No. 1. Those who got sick were killed. Three women and one man from the Warsaw transport came to us. The man was the husband of one of the three women. The Warsaw people were treated with exceptional brutality, the women even more harshly than the men. Women with children were separated from the others, led up to the fires and, after the murderers had had their fill of watching the terror-stricken women and children, they killed them right by the pyre and threw them into the flames. This happened quite frequently. The women fainted from fear and the brutes dragged them to the fire half dead. Panic-stricken, the children clung to their mothers. The women begged for mercy, with eyes closed so as to shut out the grisly scene, but their tormentors only leered at them and kept their victims in agonizing suspense for minutes on end. While one batch of women and children were being killed, others were left standing around, waiting their turn. Time and time again children were snatched from their mothers’ arms and tossed into the flames alive, while their tormentors laughed, urging the mothers to be brave and jump into the fire after their children and mocking the women for being cowards. |

Yet another evocative image is redacted by Donat.

Chapter XII

| AI Translation | Donat (180) |

|---|---|

| I had been working in the first camp for a long time, and in the evenings I returned to the second. Now I could communicate confidently and easily with the insurgents from the first camp. I was less guarded than the others and treated well. It seemed that the Ukrainians often gave me something to keep, knowing they wouldn’t search me. The boss himself brought me food and made sure I didn’t share it with anyone. I never flattered them. When I spoke to Franz, I didn’t take off my hat. He would have killed anyone else; he often whispered in my ear in German: “When you talk to me – remember, you have to take off your hat.” In these conditions, I was able to move around almost freely and discuss everything. I also had a few people with me. | For quite some time I had been working in Camp No. 1, returning every evening to Camp No. 2. This gave me a chance to make contact with the insurgents in Camp No. 1. I was watched less than the others and also treated better. Time and again, the Ukrainian guards entrusted some of their possessions to me for safekeeping because they knew I would not be searched. My superior bought me food himself and saw to it that I did not share it with anyone else. I never acted obsequious toward the Germans. I never took off my cap when I talked to Franz. Had it been another inmate, he would have killed him on the spot. But all he did was whisper to me in German, “When you talk to me, remember to take off your cap.” Under these circumstances, I had almost complete freedom of movement and an opportunity to make all the necessary arrangements. |

| AI Translation | Donat (180) |

|---|---|

| It had been a long time since transports arrived at Treblinka. Then, one day, while I was working at the gate, I noticed a different mood among the German and Ukrainian crew: a “Sztabsscharführer” in his 50s, short, stocky, with a thug’s face, he even drove out a few times in a car. At this point, the gate opened, and they brought in about 1,000 Gypsies (this was the third transport of Gypsies) – about 200 men, the rest women and children. Behind them on horse-drawn carts – all their belongings. Dirty rags, torn bedding, and other wretched things. They arrived almost unguarded. Only two Ukrainians in German uniforms led them. The two who arrived with them were also unaware of the whole truth. They wanted to settle everything formally and receive a receipt. They weren’t even allowed into the camp. Their demands were accepted with a sarcastic smile. Incidentally, they learned from the Ukrainians that they had brought victims to the death camp. They turned pale, disbelieving, and once again banged on the gate. Then the “Sztabsscharführer” came out and handed them a sealed envelope. With that, they departed. The Gypsies, like everyone else, were rounded up and burned. They were from Basarabia. | No transports had been coming to Treblinka for quite some time. Then, one day, as I was busy working near the gate, I noticed quite a different spirit among the German garrison and the Ukrainian guards. The Stabscharführer, a man of about 50, short, stocky and with a vicious face, left the camp several times by car. Then the gate flew open and about 1,000 Gypsies were marched in. This was the third transport of Gypsies to arrive at Treblinka. They were followed by several wagons carrying all their possessions: filthy tatters, torn bedclothes and other junk. They arrived almost unescorted except for two Ukrainians wearing German uniforms, who were not fully aware of what it all meant. They were sticklers for formality and even demanded a receipt, but they were not even admitted into the camp and their insistence on a receipt was met with sarcastic smiles. They learned on the sly from our Ukrainians that they had just delivered a batch of new victims to a death camp. They paled visibly and again knocked on the gate demanding admittance, whereupon the Stabscharführer came out and handed them a sealed envelope which they took and departed. The Gypsies, who had come from Bessarabia, were gassed just like all the others and then cremated. |

The published version of Rok w Treblince says “they brought in about 100 Gypsies,” 200 of which were men. This makes no sense, and is a typo. The typescript states 1,000 Gypsies arrived, containing about 200 men. Donat omits the passage defining the distribution between men, women and children, although he uses the correct 1,000 figure for the total number of Gypsies.

Chapter XIV

| AI Translation | Donat (186) |

|---|---|

| I’m already in camp no. 1. I look around anxiously. Will I be able to accomplish such a huge task? I have three more men with me. The warehouse was guarded by a Jew, about 50 years old, wearing glasses. I don’t know anything about him, as he was in camp no. 1. He was one of the conspirators. My three assistants were talking to the German boss, and I was supposedly selecting boards. I deliberately distanced myself from everyone and kept selecting. Suddenly I hear someone whispering in my ear: “Today, definitively, 5:30 p. m.” I turn around indifferently and see the Jew guarding the boards in front of me. He repeats it to me again and adds: “There will be a password.” I rub my eyes and can’t believe it. | Presently I found myself in Camp No. 1 and nervously looked around, appraising our chances. Three other men were with me. The storage shed was guarded by a Jew about 50 years of age, wearing spectacles. Because he was an inmate of Camp No. 1, I knew nothing about him, but he was a participant in the conspiracy. My three helpers engaged the German superior in a conversation to divert his attention, while I pretended to be selecting boards. I deliberately went away from the others, continuing to select boards. Suddenly, someone whispered in my ear: “Today, at 5:30 p.m.” I turned around casually and saw the Jewish guard of the storage shed before me. He repeated these words and added: “There will be a signal.” |

It is a mystery why Wiernik expresses confusion here, as he has been involved in the conspiracy to revolt and escape the camp for some time. It is a major theme in the latter part of the book. Wisely, Donat omits Wiernik’s inexplicable confusion.

Additionally, the phrase “There will be a password” conveys a quite different meaning than Donat’s “There will be a signal.” The Polish published version and the typescript also slightly differ from each other in this passage.

- Published: Powtarza mi to jeszcze raz i dodaje – “będzie hasło”. [He repeats it to me again and adds, “There will be a password.”]

- Typescript: Powtarza mi to jeszcze raz i daje nasze hasło. [He repeats it to me again and gives me our password.]

“There will be a signal” makes more sense, but doesn’t match the original. “Password” and “signal” are different words in Polish, and the word for “password” is used.

| AI Translation | Donat (187) |

|---|---|

| We all jumped up. Everyone quickly rushed to their previously assigned task. They would carry out everything conscientiously. Among the difficult tasks was: getting the Ukrainians down from the observation towers. If they had started hurling bullets at us from above, we wouldn’t have escaped alive. They had a mad passion for gold and were constantly trading with Jews. When the shot rang out, one of the traders approached the tower and showed the Ukrainian a gold coin. He completely forgot he was at his post, left his guard, and hurried down the mountain to extort the treasure from the Jew. Two other Jews were already waiting for him at the side. They caught him suddenly, finished him off, and took his weapons. The guards in the towers were also quickly dispatched. | We leaped to our feet. Everyone fell to his prearranged task and performed it with meticulous care. Among the most difficult tasks was to lure the Ukrainians from the watchtowers. Once they began shooting at us from above, we would have no chance of escaping alive. We knew that gold held an immense attraction for them, and they had been doing business with the Jews all the time. So, when the shot rang out, one of the Jews sneaked up to the tower and showed the Ukrainian guard a gold coin. The Ukrainian completely forgot that he was on guard duty. He dropped his machine gun and hastily clambered down to pry the piece of gold from the Jew. They grabbed him, finished him off and took his revolver. The guards in the other towers were also dispatched quickly. |

This passage is in the first English edition as “Two other Jews were lying in wait for him, a little to the side,” but is not included in Donat’s version. This makes Donat’s translation less clear, as he refers “one of the Jews” tricking the Ukrainian to come down from the guard tower, upon which “they grabbed him.” The original specifies this is two other Jews (so three total involved in the ambush), where Donat leaves the “they” ambiguous.

| AI Translation | Donat (188) |

|---|---|

| Suddenly, I heard a bang and at the same moment I felt a sharp pain in my left shoulder blade. I turned around, and in front of me was the watchman from the Treblinka penal camp. He was aiming his gun at me again. A 9mm automatic. I knew weapons well. I noticed the gun had jammed. I took advantage of this moment and deliberately slowed my pace. I pulled an axe from my belt. The Ukrainian ran up to me and shouted in Ukrainian: “Stop, or I’ll shoot.” I approached him and sliced his left chest open with the axe. He fell at my feet screaming, “You… you mother…” | Then I heard a shot; in the same instant I felt a sharp pain in my left shoulder. I turned around and saw a guard from the Treblinka Penal Camp. He again aimed his pistol at me. I knew something about firearms and I noticed that the weapon had jammed. I took advantage of this and deliberately slowed down. I pulled the ax from my belt. My pursuer – a Ukrainian guard – ran up to me yelling in Ukrainian: “Stop or I’ll shoot!” I came up close to him and struck him with my ax across the left side of his chest. Yelling: “Yoh tvayu mat” [you motherfucker!] he collapsed at my feet. |

It is not clear what type of gun Wiernik is referring to, and Donat removes the reference to it. Wiernik’s vague reference also contradicts the next sentence where he claims to “know weapons well.”

Donat also explains the Ukrainian’s dying utterance as “Yoh tvayu mat.” The published Polish version only says “J.. twaju m…” while the typescript has “J…Twoju mat.” The first English edition simply refers to the utterance as “a vile oath” with no direct translation, despite claiming to be a “verbatim translation” in the introduction.

Conclusions

In the introduction to The Death Camp Treblinka: A Documentary, Donat writes that the eyewitness accounts contained therein are “undramatized, unadorned, without fabrications and hollow verbiage. The nightmare of Treblinka’s hell is portrayed in simple words” (p. 15). For his plagiarized translation of Wiernik’s book, this is only partially true, because Donat deliberately excised passages that were dramatized, adorned, with fabrications and hollow verbiage. In fact, many of the phrases and sentences Donat chose to leave out can best be described as dramatized, hollow verbiage.

This calls into question the accuracy of the other translated works in Donat’s book. In the book, no one is credited as the translator of any single work, with only Alexander Donat listed as Editor of the entire work. If he did not do the translations himself, he certainly took responsibility for their veracity, including omissions such as the ones explored here. Carlo Mattogno has explored some discrepancies between Donat’s version of Samuel Willenberg’s “I Survived Treblinka,” excerpts of which are also included in The Death Camp Treblinka.[7]

All of this raises several questions. What harm does it do to Wiernik’s account if the passages are left in? Donat added back in many of the passages excluded from the first English edition. Why did he not publish a complete translation of “One Year in Treblinka”? How did he decide which passages to restore and which to keep out?

Regarding Jankiel Wiernik himself, there is no indication he was aware of these redactions for any English version, let alone approved them. Based on the anachronisms, technical impossibilities and biological absurdities in the text itself, Wiernik’s credibility has been on shaky ground for decades. Adding back in the omitted passages makes his account no more credible, although more poetic and evocative, which only contradicts the conventional story that he was “a man not familiar with the pen.”[8]

In a broader context, uncredited source plagiarism seems to be a trend with mainstream Holocaust historians. In The “Extermination Camps” of “Aktion Reinhardt”: An Analysis and Refutation of Factitious “Evidence,” Deceptions and Flawed Argumentation of the “Holocaust Controversies” Bloggers, Mattogno highlights dozens of instances of authors citing “primary” sources without acknowledging they have been lifted from secondary sources (books, online forums, etc.) without reference to the actual primary source document.[9] In addition, someone plagiarized the map included in the first English edition of Wiernik’s A Year in Treblinka, whether Wiernik himself or the publishers, who simply traced an earlier map and presented it as Wiernik’s with alterations.[10] The translation of “One Year in Treblinka” by Donat never mentions how heavily he drew upon the work done by the American Representation of the General Jewish Workers’ Union of Poland.

Finally, a note on the technology utilized for this comparison. The software used to extract the text from the Polish PDF file has only existed since 2021, yet is able to output text with a high degree of accuracy, including Polish diacritical marks. What would have taken the author of this paper weeks to transcribe Rok w Treblince manually took only a few moments, with potentially fewer transcription mistakes. The process of proofreading and correcting must still be done by humans, but the current state of text extraction software opens new possibilities for comparing original documents to the translations that have been the only widely available editions for decades.

Bibliography

- Mattogno, Carlo, Thomas Kues, and Jürgen Graf. The “Extermination Camps” of “Aktion Reinhardt”: An Analysis and Refutation of Factitious “Evidence,” Deceptions and Flawed Argumentation of the “Holocaust Controversies” Bloggers. 2nd, slightly corrected edition eds. Vol. 1. Castle Hill Publishers, 2015.

- Mattogno, Carlo, Thomas Kues, and Jürgen Graf. The “Extermination Camps” of “Aktion Reinhardt”: An Analysis and Refutation of Factitious “Evidence,” Deceptions and Flawed Argumentation of the “Holocaust Controversies” Bloggers. 2nd, slightly corrected edition eds. Vol. 2. Castle Hill Publishers, 2015.

- Mattogno, Carlo, and Jürgen Graf. Treblinka: Extermination Camp or Transit Camp? 4th ed. Holocaust Handbooks 8. Academic Research Media Review Education Group Ltd, 2024. https://holocausthandbooks.com/book/treblinka/.

- Mattogno, Carlo. The “Operation Reinhardt” Camps Treblinka, Sobibór, Bełżec: Black Propaganda, Archeological Research, Expected Material Evidence. 1st ed. Holocaust Handbooks 28. Academic Research Media Review Education Group Ltd, 2024. https://holocausthandbooks.com/book/the-operation-reinhardt-camps-treblinka-sobibor-belzec/.

- Olson, Thomas. “Jankiel Wiernik Exposed as Communist Propagandist.” Inconvenient History 17, no. 3 (2025). https://codoh.com/library/document/jankiel-wiernik-exposed-as-communist-propagandist/.

- Wiernik, Jankiel. A Year in Treblinka: An Inmate Who Escaped Tells the Day-To-Day Facts of One Year of His Torturous Experiences. First American. American Representation of the General Jewish Workers’ Union of Poland, 1944. Center for Jewish History (Box 28, Folder 490 (RG 1436)). https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE18582620.

- Wiernik, Jankiel. “Rok w Treblince.” Typescript, Manuscript. Warsaw, 1944. 11261collec. Ghetto Fighters House Archives. http://www.infocenters.co.il/gfh/notebook_ext.asp?item=41584&site=gfh&lang=ENG&menu=1.

Contains the copy used for secondary evaluation and the typescript. - Wiernik, Jankiel. “One Year in Treblinka.” In The Death Camp Treblinka: A Documentary, translated by Alexander Donat. Holocaust Library, 1979.

- Wiernik, Jankiel. Rok w Treblince. Polish. Nakładem Komisji Koordynacyjnej, 1944. Center for Jewish History (Box 28, Folder 489 (RG 1436)). https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE18582590.

Contains the primary copy used for evaluation. In general, it is the best scan and best-preserved copy of the work. - Wiernik, Jankiel. Rok w Treblince. Polish. Nakładem Komisji Koordynacyjnej, 1944. Center for Jewish History (Julian (Yehiel) Hirszhaut Papers RG 720). https://digipres.cjh.org/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE2948516.

Contains the third copy used for evaluation. It is in generally poor shape. - Władysław Bartoszewski. “Historia Jankiela Wiernika (I).” May 9, 2014. https://web.archive.org/web/20140509083502/http://wladyslawbartoszewski.blox.pl/2006/10/Historia-Jankiela-Wiernika-I.html.

Endnotes

| [1] | The only version with Wiernik’s hand-printed name is a three-page manuscript containing at least two people’s handwriting which contains several mentions of chlorine gas poisonings, which is not in the published versions of the work. Wiernik, “A Year in Treblinka, Typescript & Manuscript.” See our transcription and translation of it here, with the scans of the three original pages attached at the end. |

| [2] | A copy of the published version with the handwritten draft of the translation is available in the archives of the Center for Jewish History (CJH). Wiernik, One Year in Treblinka. CJH, Box 28, Folder 490 (RG 1436). |

| [3] | The Polish text was translated using Google Translate, with certain phrases double-checked using DeepL, and some spot-checking using Translate.com. |

| [4] | Donat does not include a Chapter IX. He skips from VIII to X. The first English edition has a Chapter VIII, IX, and X. |

| [5] | Due to the draft being written by numerous people, there is some dispute as to whether Wiernik can be considered the “author” of Rok w Treblince. For the purposes of this analysis, we refer to Wiernik as the author. |

| [6] | Olson, “Jankiel Wiernik Exposed as Communist Propagandist.” |

| [7] | Mattogno, The “Operation Reinhardt” Camps. p. 131-132. |

| [8] | Władysław Bartoszewski, “Historia Jankiela Wiernika (I).” |

| [9] | Mattogno et al., The “Extermination Camps” of “Aktion Reinhardt,” Vol. I, vol. 1; Mattogno et al., The “Extermination Camps” of “Aktion Reinhardt,” Vol. II, vol. 2. Words like “plagiarism,” “plagiarist,” “plagiarizes,” and related show up over 300 times in the book. |

| [10] | Mattogno and Graf, Treblinka. pp. 71-72. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2025, Vol. 17, No. 4

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: