On the Authenticity of the “Lachout Document”

1. Introduction

In 1987, a decades-old document caused a considerable stir in Austria. It was a circular from the Military Police Service (MPS, Militärpolizeilicher Dienst, MPD), an Austrian auxiliary force that had been founded in the post-war years to support the occupying powers in matters where they had to deal with the Austrian population, not least with former concentration-camp inmates. The internal circular RS 31/48 of the MPS dated October 1, 1948 stated that Allied investigation commissions had carried out investigations in a number of former concentration camps located in Germany, with the result that “no people were killed with poison gas” in these camps. The circular was signed by the head of the MPS, Major Müller, and a certain Lieutenant Lachout had signed for its accuracy. The purpose of the letter was apparently to fend off unjustified claims by former concentration-camp inmates. The document’s text translates as follows:

* * *

TYPED COPY

| Military Police Service | Vienna, 1 Oct 1948 |

| 10th Copy |

Circular Letter No. 31/48

- The Allied Commissions of Inquiry have so far established that no people were killed by poison gas in the following concentration camps: Bergen-Belsen, Buchenwald, Dachau, Flossenbürg, Gross-Rosen, Mauthausen and its satellite camps, Natzweiler, Neuengamme, Niederhagen (Wewelsburg), Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, Stutthof, Theresienstadt.

In those cases, it has been possible to prove that confessions had been extracted by tortures and that testimonies were false.

This must be taken into account when conducting investigations and interrogations with respect to war crimes.

The result of this investigation should be brought to the attention of former concentration-camp inmates who at the time of the hearings testified on the murder of people, especially Jews, with poison gas in those concentration camps. Should they insist on their statements, charges are to be brought against them for making false statements.

- In the C.L. [Circular Letter] 15/48, item 1 is to be deleted.

The Head of the MPS

Müller, Major

| Certified true copy: Lachout, Second Lieutenant |

L.S. | [seal] |

| C.t.c.: Austrian Republic Vienna Guard Battalion Command |

I hereby confirm that on 1 October 1948, being a member of the Military Police Service at the Allied Military, I certified the copy of this dispatch of the circular letter to be a true copy in pursuance of Art 18, para. 4 AVG (General Code of Administration Law).

Vienna, 27 October 1987 [signed Emil Lachout] |

|

* * *

In view of the explosive content, the rediscovered document must have initially hit like a bomb in politically interested circles, especially as the MPS lieutenant mentioned was still alive: he was the engineer Emil Lachout, who lived in Vienna. The document was soon referred to as the “Lachout Document”. While some right-wing periodicals in Austria and Germany greeted the document almost effusively, it was denounced as a forgery by the left, above all by the Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance (Dokumentationszentrum des österreichischen Widerstandes, DÖW).[1],[2] At that time, Emil Lachout himself was involved in a criminal trial for “Holocaust denial.” It was difficult for non-Austrians to understand the accusation of forgery. The DÖW is regarded as an institution with a strong left-wing bias. Patriotic Germans or Austrians simply did not believe that it had the necessary objectivity in a dispute about gas-chamber claims, which regarding Austria centered around the Mauthausen Camp. The trial against Lachout, which could have brought clarification, dragged on for years.[3]

The unsatisfactory situation arose in which the authenticity of an important historical document became a matter of faith. The following analysis is a late attempt to gain an objective picture of the authenticity of the Lachout Document at a distance of more than 15 years [now 35 years]. For this purpose, an evaluation of the existing literature as well as the information provided by Mr. Emil Lachout in letters to the author of these lines was carried out.[4],[5] For capacity reasons, one further source of information had to be dispensed with, namely the files of the Austrian authorities and courts, insofar as they would have been accessible. The result of the analysis was nevertheless unambiguous; it was – let this be said in advance – unexpected and surprising for the author of these lines.

The text of the circular speaks for itself (Figure 1). It touches on a still open historical question, namely “Gas chambers in the Old Reich – yes or no?”[6] This refers to whether homicidal gas chambers only existed in the so-called extermination camps (which were all located in Poland after the end of the war, and until 1990 were difficult for Western historians to access), or whether such gas chambers also existed and were operated in the other concentration camps – albeit on a smaller scale.[7]

2. The Document’s Origin

2.1. The Trial of Wiesenthal versus Rainer

After an apparent decades-long archive slumber, the Lachout Document reappeared in 1987 under mysterious circumstances. The trigger was apparently the trial of Simon Wiesenthal against Friedrich (Friedl) Rainer before the Vienna Criminal District Court.[8] Rainer is the son of the former Gauleiter of Carinthia. One of the issues during the trial was the existence of gas chambers at the former Dachau and Mauthausen camps. According to Lachout’s account,[5] the defendant Rainer asked Lachout by telephone in the summer of 1987 whether he would like to testify for him, Rainer, as a witness for the defense. Lachout agreed, and was named as a witness for Rainer in a written statement dated September 3, 1987.

The case of Wiesenthal vs. Rainer, which we cannot cover in detail here, was opened before the Vienna Criminal District Court at the beginning of September 1987. This is where the contradictions begin. While the DÖW notes that Lachout did not appear at the “main hearing” on September 9, 1987,[2] Lachout claimed that he met Gerd Honsik at the “opening” of the trial.[9] It is possible that the opening date and the first day of the main hearing were not identical. Honsik was the editor of the nationalist tabloid Halt, who was to play a role in the (re)emergence of the Lachout Document. Honsik introduced himself to Lachout, told him that he was facing a similar trial for Holocaust denial (Podgorsky vs. Honsik) and asked him whether he would also appear as a defense witness for him (Honsik) to prove that there had been no gas chambers at Mauthausen and Dachau. Lachout agreed. However, Lachout, who was summoned to testify in Rainer’s defense, was denied by the court to testify.[10] Almost as a substitute for his testimony denied by the court, Lachout then wrote an affidavit dated October 16, 1987,[11] which was forwarded to the court via Rainer’s lawyer, and then published soon afterwards in the nationalist tabloid Sieg.[12]

How Rainer came to know Emil Lachout, who was (allegedly) unknown to him, is unclear. Lachout thinks he remembers that Rainer had already spoken of a “Lachout Document” when he first made contact, mentioning the name Gerd Honsik, who was still unknown to him (Lachout) at the time. According to this, Honsik would have had a copy of the Lachout Document before Lachout, and therefore recommended Rainer to contact Lachout. This would mean that the Lachout Document had already emerged from some archive before Lachout was officially confronted with it. Consistent with this, we also read in Halt that Gerd Honsik had “tracked down” the document.[13] If this version is correct, the question naturally arises as to where Honsik found his copy of the Lachout Document. But if he did not know the document, we must ask ourselves how he and Rainer could have known that Lachout could be such an important defense witness for them.

The events described here largely follow Emil Lachout’s account. As to how and when the connection between Lachout, Honsik and Rainer came about, we have to rely entirely on the statements of those involved, and these should be viewed with skepticism, as they are partly in the nature of protective assertions against the Austrian state police and the judiciary. A connection could have been established via Honsik’s tabloid Halt, for example.

2.2. The Reemergence of the Document – in Five Versions

There are at least five contradictory and divergent accounts of the circumstances surrounding the (re)emergence of the Lachout Document. Only this much is certain: the document was published for the first time in Honsik’s tabloid Halt.[13] In the chaos of errors and confusion, polemics and disinformation, the following questions arise above all:

a) Had Honsik “tracked down” the document somewhere independently of Lachout, before Lachout also came into possession of a copy, or did he first obtain it from Lachout?

b) If Lachout did not get his copy from Honsik, where did he get it from?

c) What kind of copy does he actually have?

Version 1

In view of the significance of the newly discovered document, Prof. Robert Faurisson traveled to Vienna in early December 1987 to find out details about the creation and (re)emergence of the document. He conducted a two-day interview with Lachout, with Honsik acting as interpreter. Honsik reported on the document and Faurisson’s visit in his tabloid Halt.[14] Prof. Faurisson was told that Gerd Honsik had “tracked down” the document. The fact that two officials came to Lachout with the document – see version 2 – is not (yet) mentioned, although this event must have taken place on October 27, 1987, the day the signature was authenticated. Nor is there any mention of the fact that Lachout claims to have kept several other copies of the circular at his home at this time. There can be no doubt that Faurisson went to great lengths to get to the bottom of the matter. Even 14 years later, Lachout still regarded the interview as a “cross-examination”. In the relatively short report that Faurisson wrote after his Vienna visit, a certain skepticism cannot be denied (“If this document is genuine and if Emil Lachout is telling the truth…”).[15] Prof. Faurisson therefore behaved absolutely correctly in this matter. He returned to Paris on December 8, 1987. When he went to the Sorbonne the same day, accompanied by four of his students, the group was attacked by unknown persons. The next day, while Faurisson was waiting at a bus stop in Paris, he was attacked again and his briefcase was snatched from him, which contained “copies of several important Viennese documents as well as all the notes taken in Vienna shortly beforehand with Engineer Lachout. At least this is what Emil Lachout reported in an interview with the tabloid Sieg.[12]

Version 2

A few days after Faurisson’s visit, the state police also inquired about the origin of the document. During his first interrogation on December 11, 1987, Lachout brought up the historical commission that was in Vienna at the time, which was supposed to investigate the role of Federal President Kurt Waldheim, who was accused of war crimes during his time in the Wehrmacht in the Balkans. Lachout stated the following:[9]

“I hereby state that the Historical Commission submitted a copy of this document to me in September 1987 for review and confirmation. I was merely asked to confirm to the Commission the accuracy and authenticity of the Military Police Service and of Circular No. 31/48 of the MPS. I was only sent a copy for confirmation. After careful consideration and close examination of the copy, I confirmed the accuracy and content with my signature on October 27, 1987. I made a copy of the retyped copy submitted to me for confirmation (MPS Circular No. 31/48 dated October 1, 1948) after confirming its accuracy with my signature, in order to counteract any potential forgery.”

At the end of the interrogation, he stated:[9]

“Once again, I would like to mention that I was asked for a statement in writing by the currently active Historical Commission (WALDHEIM) in September 1987. I cannot remember the exact date and the exact name of the undersigned at the moment, but I have this letter, which I did not take with me to the interrogation, as I did not know that it was necessary.”

Some of Lachout’s statements have the character of defensive assertions. Only a few inconsistencies are pointed out in the following:

a) The Historical Commission’s Letter

If we look again at Lachout’s above statement to the state police, he says the following: First, he was “sent” a copy of the document by the historians with an accompanying letter, and then (apparently when his decision was positive), a copy of the circular was “submitted to me for confirmation.” He had given this confirmation, had his confirmation certified at the District Court of Vienna-Favoriten, and made a photocopy of the confirmed and certified circular for himself.

This account raises questions: Why did the historical commission send him a copy (i.e. photocopy) of the circular the first time, but a transcript the second time? In 1987, retyped copies were no longer made, only photocopies. And why did they not meet him in person when they were in Vienna, but only communicated with him by mail? It is therefore not surprising that a letter to Lachout was vehemently denied by the historical commission,[16] and no letter was ever presented by Lachout. In his second interrogation, he was asked again about the letter from the historical commission. However, he did not bring it with him, citing his “official secrecy.”[10]

b) Whence Did Honsik Get His Copy?

On the question of where Honsik had obtained the document, Lachout said “that I did not personally hand over a copy of the document to Mr. Honsik”, and suggested that Honsik might have obtained his copy from an archive.9 In his second interrogation,[10] Lachout said that he had sent the document to various institutes and universities, not in Austria, but for example to the “Institute for Contemporary History (Institut für Zeitgeschichte) in Freiburg im Breisgau, furthermore to the universities of London and Paris as well as to a number of other persons and institutes, I cannot give exact addresses.” He again denied having sent the document to Honsik; he did not know where Honsik got his copy.[10] However, there is neither a “University of Paris” nor a “University of London”. Paris alone has around 14 universities, and even the Sorbonne is divided into at least two universities. The name of the institute in Freiburg is also incorrect; evidently, Lachout mislocated the Munich Institut für Zeitgeschichte to Freiburg, where only the German Federal Military Archives (Bundesarchiv/Militärarchiv) and the Research Branch for Military History (Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt) are located. The whole claim is moreover implausible, especially since Lachout never submitted a corresponding cover letter, let alone a reply from the above-mentioned addressees. There is also a logical contradiction in this story: if he wanted the document distributed so widely, why didn’t he also send it to Honsik, whom he wanted to help?

c) The House Search

In an interview with the tabloid Sieg,[17] Lachout mentions a search of his home by the state police on September 15, 1987, during which various documents were confiscated. However, neither the house search nor the confiscated documents are mentioned in the two interrogations by the state police.[9,10]

Version 3

Also in December 1987, presumably shortly after the first interrogation by the state police, Circular No. 31/48 and an affidavit signed by Lachout[11] were printed by the nationalistic tabloid Sieg (edited by Walter Ochensberger).[12] It can be assumed that everything Ochensberger wrote in the Sieg article in question about the origin and reemergence of the document can be traced back to Emil Lachout. Here we read that Lachout had given the document to the newspaper Halt. In a box entitled “Portrait of the key witness” (Lachout), Sieg provides some further details.[12] According to this, “in 1948, an Allied commission” met “at the request of the Austrian federal government to investigate the events in the Mauthausen concentration camp during the Second World War up to the liberation of the camp.” Two Austrian “gendarmerie officers”, namely Major Müller as head of the “Military Police Service” (MPS) and Lieutenant Lachout, were also allowed to take part in these investigations. Lachout then “handed over thirteen files containing the findings of the investigation commission to the Austrian federal government on behalf of the MPS.”

The Sieg article goes on to say:

“He [Lachout] is also in possession of copies of important documents, one of which [the Lachout Document] he gave us, which proves that the German government had been informed since 1948 that there were no gas chambers for killing people in Mauthausen (as in Dachau).”

On Oct. 27, 1987, “shortly after his retirement”, Lachout “broke his silence and exclusively handed over a court-certified document [the Lachout Document] to the newspaper ‘Halt’.”[12]

In a later interview with Sieg,[17] Lachout indirectly confirmed that he had had a copy of Circular RS 31/48 since 1948, and had retrieved it in 1987. In response to the question “For what purpose did you take ‘Circular No. 31/48’ for yourself at the time?” he explains:

“I realized that this circular could take on historical significance. In addition, this circular is a personal record of service for me and, above all, a memento.”

In the same interview, he explained that he still had several important documents at home, including further copies of the circular, but that they had all been confiscated during the house search.

Version 4

When Lachout was in Toronto in April 1988 and Ernst Zündel’s Samizdat publishing house recorded a video interview with him, the question of the circumstances of the document’s reappearance was raised again. Lachout’s answer, which is reproduced verbatim in a DÖW brochure,1 sounds rather confused – one has to agree on this with the author Bailer-Galanda. Of course, it is not everyone’s cup of tea to present a complicated issue in front of a running camera in a precise, print-ready manner and with the necessary brevity. On the other hand, Lachout had to expect this question. He stated the following:

He had pointed out the existence of the document “years before” (i.e. before 1987). In the course of the Waldheim investigations (1987), two government officials commissioned by the “Waldheim Commission” (the historical commission set up against Waldheim) had then come to him and asked him whether he was the person who had once signed the document as genuine. They had given him a copy of the document, he had compared it with his own notes and found a match. He then confirmed his earlier signature at the District Court of Vienna-Favoriten, and the document was returned to the Office of the Federal President.[18]

There is no evidence that Lachout had already pointed out the existence of the document before 1987. In Version 4, “two government officials” now appear for the first time as the conveyors of the document – the mysterious unknowns of the affair. This “correction” of Version 2 apparently became necessary after the historians had denied an inquiry to Lachout.[16] They are now said to have commissioned two officials to deliver the document. However, the historians of that commission were not authorized to give orders to Austrian government officials. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine that the allegedly conscientious, meticulous official Lachout would simply go to the district court with two strangers who had only fleetingly identified themselves. After all, the two officials must have mumbled something about an “office of the Federal President,” because how else would Lachout think that the document was subsequently returned there? After the authentication, these two government officials disappeared without a trace and never reappeared. Logically, they must have taken the – now notarized – copy from 1948 back with them, but left a photocopy with Lachout.

Version 5

When asked by me in writing how he had obtained the copy of the “Lachout Document”, Emil Lachout gave the following account, again correcting Version 4 with regard to the “conveying officials”:[4]

“In September 1987, the Social Democratic Minister of the Interior Karl Blecha, President of the Austrian-Arab Association, sent me a copy of MPS Circular No. 31/48 of October 1, 1948, which had been in the archives of the Ministry of the Interior, via his ‘Presidential Chancellery’.

Since around 1985, the term ‘Ministerbüro’ has been replaced by ‘Präsidialkanzlei’ in Austria. This has led to confusion with the ‘Presidential Chancellery of the Federal President’. What would Austria be without a title?

In fact, during my trial in Vienna it was (temporarily) mistakenly assumed that the Presidential Chancellery of the Federal President had contacted me. It turned out, however, that the officials in question were from the ‘Presidential Chancellery’ of the Ministry of the Interior. This was later confirmed by the Council Chamber of the Regional Court for Criminal Matters, Vienna.”

The two officials had therefore neither come from the Historical Commission, nor from Federal President Kurt Waldheim or his Chancellery, but from Interior Minister Karl Blecha. Consequently, the document had not been returned to the “Presidential Chancellery of the Federal President”, but to the “Presidential Chancellery of the Federal Minister of the Interior.” On these two points, Lachout would have been subject to a forgivable error in Toronto, which would not have affected the truth of his story at its core. Of course, with all due respect for Austrian peculiarities, it sounds strange that the Ministry of the Interior should also have a “presidential chancellery”. In a telephone inquiry by the author to the Federal Ministry of the Interior in Vienna (2001), the existence of a “presidential chancellery” of the Minister of the Interior was denied.

Everything we learn about the reappearance of the document ultimately goes back to Emil Lachout. It is a story full of unproven allegations and contradictions, of mysterious unknown officials, missing documents, missing files, a conspiracy of silence by the Austrian administrations. None of the five versions stand up to closer scrutiny. Those allegedly involved (sometimes the historians, sometimes the Minister of the Interior Blecha) have credibly contradicted Lachout’s account. Gerd Honsik now lives in exile. [He died on April 7, 2018; ed.]. One can, of course, give Lachout credit for the fact that he was under pressure because of the pending proceedings against him, so that some of his statements have the character of defensive assertions. Nor do all these contradictions have anything to do with the authenticity of the Lachout Document, let alone with the correctness or incorrectness of its content. But they are not exactly suitable to strengthen confidence in this document’s authenticity.

2.3. Where was this Document between 1948 and 1987?

In order to assess the authenticity of a document, it is important that it can be traced back to its origin without any gaps. Bailer-Galanda rightly points out this requirement to authenticate documents.1 So where did the document “lie dormant” between 1948 and 1987 – if it already existed?

In his interview with the tabloid Sieg,[17] Lachout answered the question of where he thinks the files of the Military Police Service might currently be located by saying that the Allies “took all the relevant documents with them when they withdrew from Austria”. He implies that these files are being kept under lock and key, if they have not already been destroyed. Information from the Austrian State Archives is cited as evidence.[19] “The remains left behind in Austria have demonstrably disappeared with other files.”[17] However, the fact that the files were taken by the Allies contradicts Lachout’s assertion that the Military Police Service (MPS) was not an Allied but an Austrian executive body.

In his interview in Toronto, Lachout apparently did not address the archival question, but let his story begin with the two mysterious officials. Bailer-Galanda writes:1

“In any case, these confusing claims do not allow us to trace the path of the ‘document’ from its alleged creation in 1948 to its publication in 1987.”

Although this is correct, it is not suitable to refute Lachout, because if the document had really been in an Austrian archive and had been found or retrieved by some authority (Ministry of the Interior), Lachout could of course not have known this. The fact remains, however, that the document is a unique item, meaning it is completely isolated, and there are no comparable documents from which the existence of a corresponding file could be inferred.

Fourteen years later (2001), Lachout stated that he had been deployed on behalf of the League of Red Cross Societies during the Hungarian uprising on the Austro-Hungarian border in 1956. In connection with the state police’s background check of his person, which was necessary for this purpose, the “military certified copy” (he means Circular 31/48, i.e. the Lachout Document) had probably reached the Ministry of the Interior.[4] If that was so, it would have been in an Austrian archive after all and not taken away by the Allies. Of course, this is a mere assumption on Lachout’s part (at best) or disinformation (probably).

2.4. The Motives

To assess authenticity, another question is essential: “Why does a document exist at all?” When an official document is drawn up, whether genuine or false, this effort is only made because something is to be “declared.” Quod non est in actis, non est in mundo! (If it isn’t in the files, it doesn’t exist). The purpose or tendency of a document therefore allows conclusions to be drawn about the motives of the creator and the history of its creation. The intention of the “Allied Commissions of Inquiry” or the MPS is quite clear from the text itself: they wanted to fend off false testimony by former concentration camp inmates and the claims derived from it. However, since neither the existence of Allied commissions which are said to have reinvestigated the former German concentration camps in 1948, and the existence of the “MPS” cannot be proven, we can rule out this motive.

However, the three men who were directly involved in the reappearance of the circular, namely Gerd Honsik, Emil Lachout and Friedrich Rainer, had a very real motive. At the time (1987), both Rainer and Honsik were facing criminal proceedings for “National-Socialist reactivation” – Lachout followed soon after. One of the issues in the upcoming trials against Rainer and Honsik was whether or not there had been a gas chamber in the former Mauthausen concentration camp. It is possible that Honsik, Lachout and Rainer, who were convinced that the gas chamber shown today in Mauthausen was a hoax, hoped to force a discussion of the gas chamber issue by introducing the circular into their court proceedings. The Lachout document thus possibly owes its existence to tactical procedural considerations. However, the courts consistently prohibit such factual discussions (in Germany, for example, by referring to “obviousness”). It remains to be seen to what extent any of the defendants was acting in good faith in connection with the circular.

3. Did a Militärpolizeilicher Dienst Exist?

3.1. Emil Lachout’s Claims

Emil Lachout described the “Military Police Service (MPS)” as a “special unit,” “which was recruited from the ranks of the Austrian executive, and whose members were ultimately also allowed to travel with the ‘Four in a Jeep’ as representatives of Austria.”[20] Apparently, nobody in Austria in 1987 had heard of this unit, hence the issuing authority of Circular No. 31/48, in which Lachout claimed to have served from 1947 to 1955. The question of whether this “Military Police Service” existed or not is the crux of the whole affair. If the MPS did not exist at all, then “Circular No. 31/48” is also a dead document. The Austrian authorities themselves were obviously unsure at first, and they immediately set about clarifying this question. In his second interrogation by the state police, Lachout was also questioned about the MPS, and he made the following statement:[10]

“In the period from the end of the war until around November 1945, there was a ‘guard battalion,’ which subsequently constituted the military police service. This name was chosen because the term ‘military police’ did not exist for Austrians. This military police service was assigned to the Russian military commandant’s office in the Russian occupation zone. The other Allies (British, Americans and French) also had units (military), but they did not have this designation. The military police service consisted of around 500 men (Austrians), with one Russian interpreter per company (officer) and one Russian non-commissioned officer per platoon. The 500 men were at the disposal of the Russian occupation zone for Austria, and each district commandant’s office had a squad assigned to it (from 4 to 10 men). A small number of these military police officers did not work full-time.

From July 1947, I was with the Municipal Department of the City of Vienna, Ma 59 [Magistrate Dept. 59], Market Office – Food Police of the City of Vienna. As I explained in my first statement, from October 1, 1947, I was in the military police service, part-time. Soviet troops were stationed in the Trost barracks, as was the military police service (MPS with a platoon of about 30 to 40 men. The direct superior of the MPS was the commander-in-chief of the Soviet armed forces in Austria. The costs were paid from the occupation budget. The weapons were supplied by the Russian occupying forces (looted German stocks) and were supplemented with weapons found.

The task of the MPS was to travel with (or accompany) the Russian military police in the area of the Russian occupation zone in order to be available as witnesses in the event of any interventions, and to provide support as Austrians in official dealings with Austrians. Regarding uniforms, I state that the Russian occupying forces wore Russian uniforms; I and my colleagues wore a uniform similar to that of the gendarmerie without distinctions [rank insignia] with a red-white-red armband. […] The platoon stationed in the Trost Barracks was an operational platoon that was responsible for the entire Soviet occupation zone in Austria. […] I am currently looking for those colleagues who were on duty with the platoon in the Trost Barracks at that time.”

As can be seen from Lachout’s account, the “Military Police Service” (MPS) was not an Allied agency, but an Austrian auxiliary unit in the service of the Allies. The stamp used also reads “Republic of Austria.” According to Lachout, each of the four occupying powers had such an auxiliary unit at their disposal, although he himself served with the unit assigned to the Soviets. Whether these four units all belonged together as the MPS or had different names, as well as the organization and subordination of the MPS in general – all this remains nebulous. We know next to nothing about this unit, and what little we do know comes exclusively from Emil Lachout. When the DÖW asked the then Austrian Federal Minister for National Defense Robert Lichal whether there had been a “Vienna Guard Battalion” in 1948, Lichal clearly answered in the negative.[21]

3.2. Doubts about the Militärpolizeilicher Dienst

A direct proof that something, let’s call it (A), did not exist is not possible according to the laws of logic. The burden of proof in this case lies with the person who makes the claim that (A) existed. The opponent can at most prove that something else (B) existed, the existence of which excludes the existence of (A) (principle of alibi evidence), or he can gather evidence (circumstantial evidence) which makes the existence of (A) implausible.

The DÖW raised doubts at an early stage,[22] some of which were entirely justified, but other arguments fell somewhat short of the mark. For example, it was assumed that Lachout had claimed that the circular was an Allied document, which could easily be refuted. For example, Bailer-Galanda pointed out that the documents submitted by Lachout (he had submitted several other documents to the court) sometimes contained the designation “Military Police Service”, sometimes “Allied Military Command for Austria”. The author states that “according to all available documents and witness statements about the occupation period in Austria,” no Allied authorities with these designations existed. She quotes several Allied publications from that time in which a “Military Police Service” does not appear, and provides further evidence that the document could not be an Allied document.[22] At that time, Allied documents had to be written in English, French or Russian, and one would hardly have used official German abbreviations such as “F. d. R. d. A.” (Für die Richtigkeit der Ausfertigung = for the correctness of the copy) and “RS” (Rundschreiben, circular). It was also not possible for Lachout to have “certified” the correctness of the copy on October 1, 1948 “in accordance with § 18 para. 4 AVG”, as the Allies would hardly have carried out such an official act in accordance with Austrian regulations. Although this argument of the DÖW is factually correct, it nevertheless misses the point, because it overlooks the fact that – always according to Lachout – the MPS was not an Allied but an Austrian unit.

However, one can certainly cast further doubt on the existence of the MPS. First of all, it makes no sense why the various Austrian post-war governments should have persistently concealed the existence of such a unit and suppressed the relevant files. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine that a unit which for years had to deal with the population and former concentration-camp inmates could have disappeared so completely from the consciousness of the Austrians and sunk into mysterious oblivion. When the document (re)emerged in 1987, many of the former MPS members must still have been alive. If an MPS man was born in 1920, for example, then he was about 28 years old in 1948 and about 67 years old in 1987. In his second interrogation before the state police, Lachout said that he was looking for “those colleagues who were on duty with the platoon in the Trost Barracks at that time.”[10] Evidently not a single one came forward, not even a widow, son or daughter – although the Lachout case was given quite some publicity in Austria at the time.

If the MPS had been disbanded in 1955, then the men should have been transferred to other executive bodies of the state (police, army), and a takeover decree should have been issued. Nothing of the sort is known in Austria. There is also no mention of any tradition of the units, no comradeship meetings, no chronicles – a ghost unit. No ID card has ever been seen, no uniform, no identity document, no photo showing a member of the MPS in uniform. If there is such a thing, then it comes from Emil Lachout. Prof. Faurisson, who came to Vienna in 1987 to form an opinion, remembers:[23]

“I asked him [Lachout] to visit the Trost barracks so that he could show me exactly where his office would have been (even if we hadn’t been allowed in, he might have been able to show it from the outside). But for some reason, he didn’t want to show me the place.”

No wonder, then, that Lachout’s alleged superior at the MPS at the time, Major Anton Müller, never made an appearance anywhere – except in Emil Lachout’s stories.

3.3. The Archives

As Emil Lachout stated in his 1989 Sieg interview,[17] he had kept a number of documents (or copies) at home that would have been of great interest then and now – if they existed. As proof of the existence of the MPS, Lachout cited, among other things:

- 3 copies of the L[achout] Document (MPS circular no. 31/48) with copy numbers 15, 22 and 34 (i.e. in addition to copy no. 10)!

- MPS status report dated Jan. 1, 1949

- MPS status report dated March 1, 1955

- MPS letter dated Nov. 10, 1948, submission of “Expert opinion on the so-called gas van of Mauthausen”

- Letter from the Allies dated Feb. 14, 1955 on the dissolution of the MPS (end of March 1955)

- Multilingual MPS service card dated Oct. 25, 1945 [sic!] with all promotions up to Major

- MPS letter dated Oct. 27, 1948 (return of the investigation report by US Colonel Dr. [sic] Stephen Pinter)

- MPS letter dated Nov. 16, 1948, submission of the translated Pinter investigation reports concerning Mauthausen to the Federal Chancellery

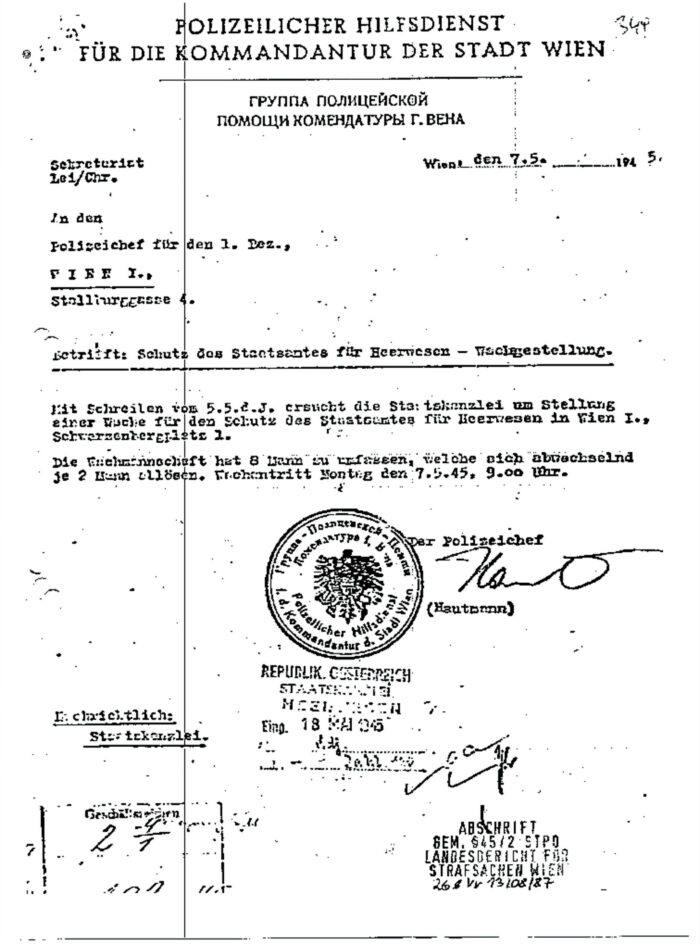

Some of these documents would be downright sensational. The only problem is that they were all confiscated by the state police during a house search on September 15, 1988 (apparently without issuing any receipt) and have since disappeared without a trace…[17] Other documents were apparently left behind by the state police, such as a letter from a “Police Auxiliary Service for the Headquarters of the City of Vienna” (“Polizeilichen Hilfsdienstes für die Kommandantur der Stadt Wien”)[24] dated May 7, 1945 (!), addressed to the “Chief of Police for the 1st District, Vienna I, Stallburggasse 4.” The letter is obviously aimed at making the existence of the MPS credible by suggesting the existence of a predecessor organization. There is not enough space here to analyze this letter. In any case, it is astonishing that there should have been an Austrian State Chancellery again on May 5, 1945 – three weeks after the conquest of Vienna by the Red Army, and three days before the surrender of the Wehrmacht. Happy Austria! Had life in Vienna really returned to normal at the beginning of May 1945 to the extent that there was a State Chancellery that had to be guarded? The most beautiful thing about this document, however, is a magnificent large round stamp with the inscription (in German and Russian): “Police Auxiliary Service for the Headquarters of the City of Vienna,” with the Austrian double-headed eagle in the center (Figure 2). Needless to say, this “Police Auxiliary Service” was as little heard of as the MPS.

Incidentally, noteworthy are the two MPS letters mentioned earlier and dated October 27, 1948 and November 16, 1948 – which have unfortunately disappeared. In them, a certain U.S. Colonel Stephen Pinter is associated with Mauthausen. I will come back to this later.

4. The Creation and Form of the Document

4.1. The Copying Process

Emil Lachout made contradictory statements about the origin of the circular on various occasions, e.g. to the state police[9,10] or during the 2nd Zündel trial in Toronto.[25] According to this, he himself had drafted the circular at the time and prepared it for his superior, Major Müller, to sign. Müller signed it in front of him. He (Lachout) then had the copies made in the office, which he signed and stamped correctly. In addition, the circular had been translated into the three languages of the Allies and confirmed by a control officer. Only then was it released for distribution and distributed to all military commands in the Russian zone. Some copies are also said to have been sent to the Allies and the Austrian federal government.[10] Lachout’s account once again raises questions:

a) On the Copying Process

In the hectograph process, which was widespread at the time, the original had to be typed onto a special foil (matrix), from which up to 100 copies could be “pulled off”. It is unclear whether official circulars were also hectographed. Otherwise, the only option for reproducing a document at that time was probably a printing process, whereby signatures could also be reproduced in facsimile. For small quantities, there was still the option of copying by typewriter. According to Emil Lachout, around 50 to 60 copies of the circular were produced and distributed. Did people really type out a circular 50 to 60 times back then, even if it was only half a page long? Of course, it was possible to make several carbon copies of a letter – but were they considered to be valid documents?

b) Certification of Accuracy

Lachout allegedly signed each of the 50 to 60 copies , thus certifying the correctness of each copy. Even if one considers the difficult post-war circumstances, this procedure still seems very cumbersome. Did Major Müller not have a facsimile stamp with his signature?

4.2. Which Version of the Document Is Actually Available?

The original of the MPS circular RS 31/48, which was signed by Major Müller on October 1, 1948 and certified as correct by Lieutenant Lachout, has been lost (if it ever existed). Theoretically, it should be in an Austrian archive. A complicated situation has arisen today due to copies, subsequent authentications and photocopies. The question is: What kind of copy does Emil Lachout actually have in his hands? That depends on which of the five versions presented above you want to believe.

According to Version 3, Lachout took “copies of important documents” home with him in 1948, with which the then 20-year-old would have demonstrated an almost prophetic historical foresight. However, he only presented this version to Sieg.[12,17] The later Versions 4 and 5 no longer mention it, probably due to the problem of transcription. The document known today as the Lachout Document is not one of the typed copies (“10th copy”) made for distribution at the time, but, as Lachout also admitted to the state police,[10] only a retyped copy of the 10th copy made at the time.

According to Versions 4 and 5, the document, i.e. the retyped copy of the 10th copy, was now presented to him by two unknown government officials. Theoretically, at this point the text should have begun with the words “[retyped] copy” and “Military Police Service” and ended with the certification of accuracy, Lachout’s signature and the stamp “Republik Österreich – Wachbataillon Wien – Kommando.” Everything else are later additions (Figure 1). On the yellowed post-war paper of this copy, there should be the stamps from October 1987. Then, of course, the officials took their now certified and stamped copy back with them, allowing Lachout to make a photocopy. Lachout can therefore only have a photocopy of this retyped copy, on which the stamps only appear as a copy.

The notarized copy with the genuine notary-fee stamps was therefore taken back by the government officials. It never reappeared, no authority, no Minister of the Interior ever made use of the document. But if the Austrian authorities wanted to suppress the document – why did they go to Lachout with it in the first place? Questions upon questions… and every answer raises new questions.[26]

4.3. Formal Aspects of the Document

As already mentioned, the original document begins with the issuing authority “Military Police Service” and ends with the stamp “Republik Österreich – Wachbataillon Wien – Kommando.” Everything else is a later addition. Measured against the requirements that must be placed on a document, even if it is only the copy of a circular, the following is noticeable on closer inspection:

a) No letterhead

Prof. Dr. Robert Faurisson on the Lachout Case

“I am not absolutely sure whether we can trust Emil Lachout. I had real difficulty getting more precise information about the ‘commission’ from him.”

(Letter to the author, June 23, 2002)

“I asked him [Lachout] to visit the Trost barracks so that he could show me exactly where his office would have been (even if we hadn’t been allowed in, he might have been able to show it from the outside). But for some reason, he didn’t want to show me the place. […] As you know, or should know, a mythomaniac is not content to lie; he lies almost constantly. Lachout, for example, can’t send you his own opinion or statement without presenting it as an ‘expert opinion’ (sic). That is already a lie, or at least an inadmissible kind of pressure or distortion. […]

PS: After Zündel had a long conversation with him after Lachout’s testimony in court, he told me he couldn’t trust the man.”

(Letter to the author, Aug. 5, 2002)

The document was not typed on letterhead with a pre-printed header and footer, but on blank paper. Lachout made the following comments on this to the state police:[10]

“Internally, nothing was mentioned apart from the name MPS. In other correspondence and files, stamps were used as headers (Cyrillic letters), for example, the header read: ‘District headquarters of the Red Army in Favoriten’ (Bezirkskommandantur der Roten Armee in Favoriten). Underneath, it was written in Russian ‘Aust. Military polic service’ (‘Österr. militärpolizeilicher Dienst’), in brackets also in German.”

Lachout therefore claims that no letterheads were used in the MPS’s internal correspondence. This does not seem very credible – even in view of the post-war circumstances. The lack of a letterhead had already been criticized by the DÖW, but they were fixated on the idea of an Allied document:1

“It is inconceivable that an Allied authority did not have its own letterhead on its official paper with the name of the responsible headquarters.”

b) Retyped copy of a retyped copy?!

Above the first word of the actual text – “Militärpolizeilicher Dienst” – commonly ignored, the word “ABSCHRIFT” (retyped copy) is written in the top line on the right. Since 50 to 60 numbered copies of the original were allegedly typed, it would not have been necessary to mark each one as a retyped copy. If “ABSCHRIFT” is nevertheless written, this can only mean that retyped copy was made of the 10th copy of the circular. The Austrian state police apparently pointed out this inconsistency to Lachout during his second interrogation. He accepted the logic of his interrogators, according to which the present document should actually only be the retyped copy of the 10th copy, by saying:[10]

“I cannot say why a retyped copy in particular of the 10th copy exists.”

Later, during his Sieg interview of 1989,[17] he gave the impression that he himself had arranged for having the 10th copy deliberated retyped at the MPS, and had taken this retyped copy with him (cf. Version 3).

In the case of a retyped copy, the lack of a letterhead would of course explain itself. But Lachout did not use this argument at all. He merely claimed that no letterheads were used in the MPS’s internal correspondence (cf. Point a). If he really did take a retyped copy of the 10th copy home with him in 1948, then the secrecy surrounding the reappearance of the document and the various legends are incomprehensible (either Honsik found it, or the historians, or two officials came up with it). If two officials really approached him with the document, one has to wonder why the Austrian State Archives or the Ministry of the Interior did not even have one of the 50-60 copies at their disposal, but only this second-rate retyped copy.

c) Numbered copies

Numbering individual copies of a circular is unusual, as this was only done for a small circle of recipients with a high level of secrecy. In his second interrogation by the state police, Lachout stated:[10]

“that this was an internal decree to the guard posts (squads) at the Allied district military headquarters in Austria. […] Furthermore, I explain the expression 10th copy by the fact that a circular letter was distributed according to an existing distribution key. In such circulars, the word ‘copy’ (‘Ausfertigung’) was typed, the number was inserted by hand.”

Since the number of the copy on the Lachout document is not hand-written but typed, today’s copy can only be a retyped copy of the 10th copy according to the logic of the state police, which Lachout did not contradict.

d) No signature

The signatory is listed as “The head of the MPS: Müller, Major”, although his signature is missing. As Lachout states, Müller only signed the original, which has been lost – if it ever existed. Why did Müller, supposedly head of a force of 500 men, not have a facsimile name stamp?

e) The rubber stamp

The only “official” thing about the “original” document is a simple three-line stamp, the kind you can make with a toy stamp box for children. Two points stand out:

- Although it is supposed to be a circular from the “Military Police Service”, the stamp reads “Republic of Austria – Guard Battalion Vienna – Command”. However, a guard battalion is not the same as a police auxiliary unit. According to the DÖW’s research, there was no “Guard Battalion Vienna” in 1948.1 This is a serious indication against the authenticity of the stamp and the document.

- Even for the post-war period, the rubber stamp used for an organization like the MPS is a bit poor, especially since the predecessor organization “Police Auxiliary Service” – whose existence is just as doubtful – already had a magnificent large round rubber stamp on May 7, 1945 (three weeks after the fall of Vienna! See Fig. 2).

From the fact that Lachout was apparently questioned quite thoroughly about the formal aspects of the circular during his second interrogation, one can conclude that the State Police also had doubts about its authenticity, and that they knew nothing about the origin of the document from an Austrian archive (the “two government officials”).

4.4. The Certifications

With the exception of the first stamp “Republik Österreich – Wachbataillon Wien – Kommando,” the various postmarks and stamps were all applied in October 1987. First of all, Emil Lachout confirmed on Oct. 27, 1987, that he was the one who had signed “For the correctness” on Oct. 1, 1948. This confirmation cost a 120-Schilling stamp, which was marked by a round rubber stamp of the District Court of Vienna-Favoriten. The district court also confirmed Lachout’s identity and the authenticity of his signature, which cost another 120 schillings. The remaining 40 schillings (2 court cost stamps of 20 schillings each) were due for the registration of the process.

The stamps and fee stamps from October 1987 say nothing about the authenticity of the document itself. Finally, the five-line stamp in the left margin is a private Lachout stamp. All the stamps and fee stamps cannot ultimately hide the fact that the Lachout Document is a unique item of dubious origin. Apart from the present circular no. 31/48, not a single other MPS document has surfaced to date.

5. Critique of the Text

5.1. The Document’s Key Message

Immediately after the capture of the concentration camps, the victorious powers carried out investigations to uncover alleged or actual German crimes. In 1945, based on the Allied reports and the testimony of former prisoners, there was hardly one of the fifteen or so large German concentration camps for which the existence of a homicidal gas chamber was not claimed. These included camps where such gas-chamber claim has since been tacitly dropped (Buchenwald, Bergen-Belsen, etc.) or where the existence of a gas chamber is highly doubtful (Dachau, Mauthausen, Sachsenhausen, etc.). Still others are excluded from historical research by criminal law in many European countries.

As is well known, the core statement of the Circular is that in 1948 the Allies undertook a review of their first reports from 1945 and sent “Allied Commissions of Inquiry” to a number of former concentration camps for this purpose. Paragraph 1 of the circular states that “no people were killed by poison gas” in the 13 camps mentioned. Paragraph 2 refers to an earlier MPS circular RS 15/48, which has been lost – if it ever existed. Emil Lachout states that it had similar contents, but that not all 13 camps were listed because the investigations were still underway.[15]

However, such quasi-revisionist investigations are diametrically opposed to the post-war policy of the Allies, whose war-crimes trials were still in full swing. Even the fact that a document contains something true (in the case of Circular 31/48, the non-existence of gas chambers in certain camps) does not, of course, prove that the document is genuine. Renowned revisionist researchers have had doubts about its authenticity from the very beginning. Apart from the non-existence of certain gas chambers, what about the other statements in the document? This brings us to the problem of the “Allied Commissions of Inquiry.”

5.2. Allied Commissions of Inquiry of 1948

The circular shows, and Emil Lachout testified several times to this effect,[27] that the Allies re-investigated claims about former German concentration camps in 1948, in order to review the earlier Allied reports, most of which had already been drawn up in 1945. He himself and his MPS superior, Major Müller, took part in the investigation of the former Mauthausen concentration camp as Austrian observers. The DÖW focused its criticism on the term “Allied Commissions of Inquiry”, which did not exist in this general form. However, the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC) in London did exist:1

“The trial against those responsible for the Mauthausen concentration camp was heard by a US court in Dachau, where the question of killings by poison gas was also dealt with. So it would be downright absurd if the same authority [UNWCC] that conducted these extensive trials had drawn up a document of this kind [Lachout Document].”

While the UNWCC was certainly not in control of the court running the Dachau trials, as that was probably the U.S. War Department. Otherwise, this DÖW’s argument cannot be dismissed out of hand: the Allies or the Americans, who were still conducting war crimes trials at the time, did not even think of questioning and reviewing their earlier concentration-camp reports. So, what about the “Allied Commission of Inquiry” claimed by Lachout, which is said to have been re-investigating Mauthausen in 1948? In fact, there were two American (not Allied!) commissions of inquiry in 1948/49, which were also active in Germany and Austria: the Simpson/van Roden Commission, and the Baldwin Committee.

However, these commissions were not concerned with the (alleged) crimes in the German concentration camps, but with the unlawful actions of the US military jurisdiction.[28] The actions of the American investigators and courts-martial in preparing and conducting the war-crimes trials, especially the so-called Malmedy Trial, had led to protests against this type of justice, among others by German bishops and the German lawyers of the defendants. Reports appeared in U.S. media about brutal mistreatment of the defendants (mostly young soldiers of the Waffen SS), catastrophic prison conditions, methods of psychological torture such as total isolation, mock trials (with death sentences and mock executions), false witnesses, false confessors, obstruction of the defense, etc. These hair-raising conditions, which made a mockery of U.S. legal tradition, threatened to shatter the credibility of the war-crimes trials and the reputation of U.S. justice. A campaign was kicked off in the U.S. against mass executions in the Landsberg war-crimes prison under the slogan “Stop the hanging machine.” In May or June 1948, Secretary of the Army Royall – reluctantly – commissioned two army judges from the Judge Advocate General Department (JAGD), namely Colonel Gordon Simpson and Colonel Edward Leroy van Roden, to form a commission of inquiry. This so-called Simpson/van Roden Commission arrived in Munich on July 12, 1948, and submitted a report on September 15, 1948, which was released for publication by the Minister of the Army – reluctantly and only under public pressure – on January 6, 1949.[28]

When Lachout talked about a commission of inquiry that is said to have been in Mauthausen in 1948, this fits in well with the activities of the historical Simpson/van Roden Commission. Lachout provides some details. The “Allied Commission of Inquiry” is said to have consisted of two investigators from the military police of each of the four occupying powers and two Austrian observers (Müller and Lachout). The head of the commission was allegedly the lawyer of the US War Department, Colonel Stephen F. Pinter. The commission was dissolved in 1949 and only met again when necessary.[25] During his Sieg interview,[17] Lachout mentions two relevant MPS documents in connection with an alleged investigation report by Pinter, which were confiscated from him during a house search (cf. Section 3.3). However, his account needs to be corrected. The task of the Simpson/van Roden Commission, and later of the so-called Baldwin Committee, was to review U.S. military jurisdiction and its unlawful methods, not to re-inspect the former German concentration camps. Apart from the Lachout Document, there is no evidence that Simpson and van Roden sent one or more sub-commissions to the former concentration camps. Moreover, the Simpson/van Roden commission was a purely U.S. event. According to Lachout, however, the mysterious “Mauthausen Commission” had an Allied composition – despite the “Cold War” that had broken out in the meantime (start of the Berlin Blockade on June 24, 1948).

5.3. The Non-Existing Report of the Imaginary Mauthausen Commission

Where there is a commission of inquiry, there is also a report. As is well known, an American report on KL Mauthausen was drawn up as early as June 1945.[29] If there was another Allied commission in Mauthausen in 1948, it too should have delivered a report on its findings. However, no such report has appeared to this day. This makes it all the more exciting to suddenly find a reference to such a second Mauthausen report. In response to two articles by Till Bastian in Die Zeit,[30] the then 80-year-old former Major General of the German Wehrmacht, Otto Ernst Remer, published a brochure entitled Die Zeit lügt![31] The list of sources for this brochure now reads [56]: S. Pinter, Mauthausen Report, Supplement 3/Us-Army Chemical Corps, Aug. 5, 1948 [sic].

The historical Colonel Stephen F. Pinter is named as the author of a second Mauthausen report, and August 5, 1948 as its date! This report would be a minor sensation, because it would of course be the missing proof of the Mauthausen Commission of 1948 claimed by Lachout. However, neither an archive location nor an archive signature is mentioned. It is also strange that the report is said to have come from the same US unit, the 3rd U.S. Army Chemical Corps,[29] whose 1945 report was supposed to have been checked! In what context is this mysterious report actually quoted? Note 56 is in the caption of a diagram, which reads:

“Figure 1: Evaporation rate of hydrogen cyanide from the Zyklon B carrier material according to the US Army Chemical Corps [56].”

The diagram is included in the Remer brochure as an illustration of the slow vaporization of hydrogen cyanide (HCN). Although it seems unusual to deal with a typically revisionist question (vaporization rate of hydrogen cyanide) as early as 1948, it is not impossible. For example, the Polish-Soviet commission working in Majdanek in the late summer of 1944 determined the filling weight of the Zyklon B cans by weighing them before and after the hydrogen cyanide had evaporated.[32] We now hear from Germar Rudolf that he himself wrote most of the Remer brochure in question and that the diagram was sent to him by Emil Lachout.[33]

Germar Rudolf on the Lachout Case

“In early 1997, after I had just launched my new German-language periodical whose title translates to Quarterly for Free Historical Inquiry, I got in touch with Emil Lachout in an attempt to get from him as complete a set as possible of all the historical documents he owned. I planned on using them to write papers for my fledgling journal, potentially in cooperation with Mr. Lachout. Mr. Lachout promptly sent me boxes of photocopies of all the material he had, or so he claimed. For days, I sat in my home’s sunroom and backyard, inspecting and reading the vast documentation.

However, I quickly realized that they all consisted of papers Lachout had written himself. Many if not most of them he had rubber-stamped with all kinds of seals, making them look like official documents. Many of them were titled as “expert reports.” He justified this as a judicial tactic, because documents declared as such could not be ignored by an Austrian court. He had inundated the Viennese courts with such documents, most of them complete trivial, if not vapid in nature.

One of the things I hoped to find was an original or copy of Pinter’s “Mauthausen Report,” from which Lachout claims to have taken the data for an evaporation chart he had sent me some six years earlier. However, the vast documentation contained no trace of any such report. In fact, the vast documentation didn’t really contain anything of use.

Utterly disappointed, I decided not only to delete all references to this Pinter’s report from all future editions of my expert report, but I also abstained from ever using anything coming from Lachout. I eventually recycled the ‘document’ collection he had sent me.”

It obviously goes back to corresponding company publications by DEGESCH (Irmscher 1942) and Detia Freyberg GmbH (1991), as later reproduced by Leipprand,[34] but the evaporation times in the diagram are shown 10 times longer than in reality (probably by mistake). Because of this error, Rudolf also had doubts about the diagram. In the first edition of the Rudolf report of July 1993, he still quoted the diagram of the (alleged) Pinter report, but tacitly ignored the data contained in it, thus indirectly showing his disbelief.[35] In the later versions of the Rudolf report, the (alleged) Pinter report is no longer mentioned.[36] Germar Rudolf’s statement is further proof that leading revisionists were skeptical of Emil Lachout’s statements, and that the legend of an Allied commission in Mauthausen headed by Pinter goes back to Lachout.

The report dated “August 5, 1948” mentioned in the Remer brochure, and of such burning interest to us, thus also turns out to be a phantom. We do not know the real final report by Simpson and Van Roden, but the statement “no gas chambers” would have been so sensational that we would have heard about it. One could argue that the results should have remained secret, but why of all units were they revealed by the MPS, which was active in the Soviet occupation zone of Austria, after the outbreak of the Cold War?

Let’s return to the aforementioned U.S. Colonel Stephen F. Pinter, who in the post-war years was an attorney for the U.S. War Crimes Investigation in Germany and Austria. Pinter, a genuine German-American and a lawyer by profession, was not without sympathy for the defeated Germans, and apparently conducted his investigations against the defendants quite objectively, which sets him apart from the majority of his colleagues. Very little is known about this deserving man, and he is probably only known to many because of his letter to the editor of a U.S. Sunday newspaper (1959), in which he comments on the gas chamber issue.[37]

When Prof. Faurisson spoke with Honsik and Lachout in Vienna in December 1987, there was apparently no mention of Pinter. However, Faurisson immediately recognized that Lachout’s statements, the Lachout document and the Pinter letter confirmed and complemented each other, and so he wrote:[15]

“Does this document not confirm the statement made by a certain Stephen Pinter in 1959?”

A year later, Emil Lachout moreover suggested that the Mauthausen Commission (1948) had been headed by Pinter, meaning that he listed two (alleged) MPS letters (cf. Section 3.3) that referred to Pinter’s (alleged) Mauthausen Report, which he claimed had (allegedly) been confiscated during a Police search of his home.[17] Lachout later repeated his statement that Pinter had been the head of a second Mauthausen Commission.[5] It is just too bad that no such commission ever existed, and so it cannot be true that Pinter headed it. Presumably, the historical Colonel Pinter was only brought into play to give the fictitious “Allied Commission” a certain credibility.

6. Final Observations

Apart from the Lachout Document, Emil Lachout’s stories as well Lachout’s “Pinter Report,” there is nothing to prove the activities of any Allied investigation commissions that are said to have been active in former German concentration camps in 1948, especially at the Mauthausen Camp. Corresponding reports have never emerged. These commissions are a phantom.

After all, their existence would have contradicted the re-education policy of the Allies. There is just as little evidence of the “Military Police Service” in Austria in the post-war years. Here too, all information and documents that are supposed to directly or indirectly make the existence of the MPS credible can ultimately be traced back to Emil Lachout. This unit is a ghost unit. That is why the history of the origin of the Lachout Document cannot be correct. There are at least five versions full of inconsistencies and contradictions as to how and where the document appeared in 1987. This leaves only one conclusion:

This Circular Letter is a forgery.

For the purpose of this study, it may remain open who the forger is.

For many who previously believed in the document, this realization may come as a surprise. The fact that the belief in the authenticity of the document has persisted to this day is not least due to the fact that the critics at the DÖW combined their research findings with fierce polemics against revisionism, thus shaking confidence in their own scientific integrity.

The motive for the falsification was presumably trial tactics, namely to force a discussion of the gas-chamber issue (especially in connection with Mauthausen) in the criminal proceedings against Rainer and Honsik. However, the court did not agree to this and left the proceedings against Lachout pending for years, probably precisely in order to avoid a discussion of the gas-chamber issue. Today, the document is a burden for revisionist research into contemporary history, as opponents such as the DÖW will continue to happily accuse the entire revisionist movement of this forgery. But this accusation is not justified, because even renowned revisionists (Faurisson, Zündel) were skeptical from the very beginning. However, it could not be their task to clarify the confused history of the document. A scientist like Prof. Faurisson, who had traveled to Vienna in 1987 to form an opinion, clearly held back.

In any case, the Lachout document must be dispensed with as evidence in the question of whether or not there were any homicidal gas chambers in concentration camps located on the territory of the “Old Reich,” and this also applies to the question of the Mauthausen gas chamber. Incidentally, just because the document is a forgery does not mean that everything written in this “Circular RS 31/48” must be false. In this context, a sentence from a judgment of the Vienna Higher Regional Court is noteworthy.[38] It is so convoluted, however, that one has to read it several times to wrap one’s head around it. There, the court makes a subtle distinction between an argument that there had been no mass extermination by poison gas in individual, specifically named concentration camps (apparently not punishable) and the “so-called ‘gas chamber lie’“, according to which “mass extermination by poison gas in concentration camps is wrongly imputed to the National Socialists per se” (punishable). However, the court assumed that the document had also been used for the latter, punishable argumentation, which meant that civil servants had a duty to intervene against “such neo-Nazi activities”.

In any case, the various trials in connection with the Lachout Document did nothing to clarify the gas chamber issue at Mauthausen. The trial against Emil Lachout dragged on for years. It was obviously not expected that Lachout would turn the tables and sue the Republic of Austria in Strasbourg for denial of a human right (by delaying the trial). Lachout won this case[39] – not in the matter of the gas chamber, of course, but for delaying the proceedings – and the Republic of Austria had to pay him “just reparation.”

* * *

This paper was first published in German as “Zur Echtheit der Lachout-Documents” in Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, Vol. 8, No. 2 (2004), pp. 166-178.

Endnotes

| [1] | Brigitte Bailer-Galanda, Wilhelm Lasek, Wolfgang Neugebauer, Gustav Spann (Dokumentationszentrum des österr. Widerstandes), Das Lachout-“Dokument” – Anatomie einer Fälschung, DÖW, Vienna 1989. |

| [2] | Brigitte Bailer-Galanda, “Das sogenannte Lachout-‘Dokument’”, in: DÖW, Bundesministerium für Unterricht und Kunst (eds.), Amoklauf gegen die Wirklichkeit. NS-Verbrechen und revisionistische Geschichtsklitterung, 2nd ed., DÖW, Vienna 1992. |

| [3] | On the Lachout Case, see the article by Johannes Heyne, “Die ‘Gaskammer’ im KL Mauthausen – Der Fall Emil Lachout”, Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung Vol. 7, Nos. 3&4 (2003), pp. 422-435. |

| [4] | Emil Lachout, Letter to the author dated Aug. 5, 2001. |

| [5] | Emil Lachout, Letter to the author dated Sept. 25, 2001. |

| [6] | On this, see Reinhold Schwertfeger, “Gab es Gaskammern im Altreich?”, Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, Vol. 5, No. 4 (2001), pp. 446-449. |

| [7] | Of the 13 former German concentration camps mentioned in the Lachout Document, nine were located on the territory of the “Old Reich” (“Altreich”) and the remaining four in the territories annexed in 1938. None of the so-called extermination camps, which today are all located on Polish soil, are mentioned. The term “Altreich” refers to Germany within the borders of 1937. This can lead to misunderstandings, as five concentration camps (Auschwitz in eastern Upper Silesia, Mauthausen in Upper Austria, Natzweiler in Alsace, Stutthof near Danzig, Theresienstadt in the Reich Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia) were strictly speaking not located on the territory of the Old Reich, as the territories in question were only annexed to the German Reich between 1938 and 1940. |

| [8] | Trial of Wiesenthal vs. Rainer (Strafbezirksgericht Vienna, Ref. ZL 9 V 939/86). |

| [9] | Bundespolizeidirektion Vienna, Staatspolizeiliches Büro, transcript (Ref. I – Pos 501/IV B/14b/87 res) dated Dec. 11, 1987 (1st interrogation of Lachout). |

| [10] | Bundespolizeidirektion Vienna, Staatspolizeiliches Büro, transcript (Ref. I – Pos 501/IV B/14b/87 res) dated Feb. 2, 1988 (2nd interrogation of Lachout). |

| [11] | Emil Lachout, sworn affidavit dated Oct. 16, 1987, certified by District Court Vienna-Favoriten (G 1350/87). |

| [12] | Walter Ochensberger (ed.), Sieg No. 11/12 (Nov./Dec. 1987), pp. 7-9. |

| [13] | Gerd Honsik, “Regierungsbeauftragter bricht sein Schweigen – Mauthausenbetrug amtsbekannt! Major Lachouts Dokument exklusiv im Halt,” Halt No. 40, Vienna, Nov. 1987. |

| [14] | Gerd Honsik, “Das Dokument ist echt! Faurisson eilt nach Wien!”, Halt No. 41, Vienna, Dec. 1987. |

| [15] | Robert Faurisson, “The Müller Document”, The Journal of Historical Review, Vol. 8, No. 1 (1988), pp. 117-126. |

| [16] | Letter by Prof. Dr. Manfred Messerschmidt (Militärgeschichtliches Forschungsamt Freiburg) dated July 14, 1988 to the DÖW. |

| [17] | “Exclusiv-Interview mit Herrn Emil Lachout,” Sieg No. 6 (1989), pp. 16-19. |

| [18] | See note 1, p. 11. |

| [19] | Information of the Austrian State Archives, Sept. 21, 1988 (ref. GZ 0695/0-R/88); in the court files of the trial DÖW vs. Lachout, quoted acc. to note 14, p. 16. |

| [20] | See note 17, p. 9 (box). |

| [21] | Dr. Robert Lichal, Bundesminister für Landesverteidigung, Letter to Dr. Wolfgang Neugebauer, DÖW, dated Feb. 20, 1989; reproduction in Bailer-Galanda et al., note 1, p. 16. |

| [22] | See note 1, pp. 12-16. |

| [23] | Robert Faurisson, letter to the author, Aug. 5, 2002. |

| [24] | Polizeilicher Hilfsdienst für die Kommandantur der Stadt Wien, Letter dated May 7, 1945 (copy sent by Emil Lachout to the author). |

| [25] | Barbara Kulaszka (ed.), Did Six Million Really Die? Report of the Evidence in the Canadian “False News” Trial of Ernst Zündel, Samisdat Publishers Ltd., Toronto 1992. |

| [26] | All illustrations reproduced anywhere today – including the one shown here – are obviously always photocopies of Lachout’s copy. It should be noted that the document is sometimes only partially reproduced. According to Emil Lachout (2001), the illustration of Circular No. 31/48 (Lachout document) shown here reproduces the document in full (Figure 1). |

| [27] | R. Faurisson, op. cit. (note 15), pp. 119, 123f., E. Lachout, op. cit. (note 4), p. 8, and idem, op. cit. (note 5), p. 16. |

| [28] | Cf. Ralf Tiemann, Der Malmedyprozess. Ein Ringen um Gerechtigkeit, Munin-Verlag, Osnabrück 1990. |

| [29] | Report of Investigation of Alleged War Crimes [in Mauthausen], Headquarters Third U.S. Army, Office of the Judge Advocate, by Eugene S. Cohen, Major and Investigator-Examiner, 514th Quarter Master Group, 17th June 1945 (IMT Document 2176-PS) |

| [30] | Till Bastian, “Die Auschwitz-Lügen”, in: Die Zeit, No. 39 dated Sept. 18, 1992; Till Bastian, “Der ‘Leuchter-Report’”, in: Die Zeit, Nr. 40 dated Sept. 25, 1992 . |

| [31] | Otto Ernst Remer (ed.), Die Zeit lügt!, Remer-Heipke Verlag, Bad Kissingen 1992, cf. http://web.archive.org/http://vho.org/D/Beitraege/Zeit.html. |

| [32] | See J. Graf, C. Mattogno, Concentration Camp Majdanek: A Historical and Technical Study, 3rd ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Uckfield, 2016, pp. 125f. |

| [33] | Germar Rudolf, letter to the author dated May 13, 2004. |

| [34] | See Wolfgang Lamprecht (= Horst Leipprand), “Zyklon B – eine Ergänzung”, in: Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1997), pp. 2-5; English: Horst Leipprand, “Zyklon B – a Supplement,” Inconvenient History, 10(2) (2018); https://codoh.com/library/document/zyklon-b-a-supplement/. |

| [35] | Rüdiger Kammerer, Armin Solms (eds.), Das Rudolf Gutachten. Gutachten über die Bildung und Nachweisbarkeit von Cyanidverbindungen in den “Gaskammern” von Auschwitz, Cromwell Press, London 1993, pp. 58f.; see https://web.archive.org/www.vho.org/D/rga1/verdampf.html. |

| [36] | G. Rudolf, Das Rudolf Gutachten, 2nd ed., Castle Hill Publishers, Hastings 2001; idem, The Rudolf Report, Theses & Dissertations Press, Chicago, IL, 2003. |

| [37] | Stephen F. Pinter, Letter to the Editor, in: Our Sunday Visitor (Huntington, Indiana), June 14, 1959, p. 15 |

| [38] | Verdict of Upper District Court Vienna dated Sept. 10, 1990, Ref. Zl. 27 Bs 199/90; quoted acc. Bailer-Galanda, op. cit. (note 2), pp. 81f. The case concerned a private lawsuit brought by Emil Lachout against DÖW employee Brigitte Bailer-Galanda and several journalists, where Bailer-Galanda was acquitted in two instances. |

| [39] | European Council, Council of Ministers, Complaint No. 23019/93, accepted on 8. Oct. 1999 during the 680th session of ministerial delegates. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2020, Vol. 12, No. 3; originally published in German as “Zur Authentizität des Lachout-Dokuments,” in: Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung, Vol. 8, No. 2 (2004), pp. 166-178.

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: