Partisan War and Reprisal Killings

An attempt to organize German reprisals during the military campaign against the USSR

Since the publication of Daniel Goldhagen's book Hitler's Willing Executioners and the general attention, which the Anti-Wehrmacht propaganda exhibition received in Germany,[1] the center of gravity of the discussion about the 'Holocaust' has changed. At least today the attention is directed less intensively to the alleged high-tech mass murder in “homicidal gas chambers,” which are in every regard still totally inconceivable even today, but considerably more to the actual or only claimed mass murder behind the eastern front, allegedly committed above all, but not exclusively, by the so called Einsatzgruppen and committed especially, but not only, against Jews residing in the then Soviet Union. Opinions about this subject vary widely within historical revisionism from positions, which are not very different from the established opinion, to those who deny such mass murders completely. The following article tries to summarize the current knowledge from one revisionist viewpoint, which revised exaggerated claims of mass murder and brings the issue into the context of wartime reprisals-and reprisal excesses-against illegal partisans. We hope that this may trigger a vivid discussion and a start into further, more detailed research into this field.

Allied Reprisals against Germans

German newspapers rarely carry articles about reprisals threatened or implemented by the western Allies at or after the end of the war. However, the Stuttgarter Zeitung, for example, reported that the French had threatened reprisal executions at a ratio of 1:25 even in the event that shots would be taken at their soldiers at all, regardless of the actual outcome.[2] On April 4, 1992, the Paderborner Zeitung reported an incident where the Americans had taken harsh revenge for the death of their General Maurice Rose, who had been shot in regular combat: 110 German men not involved in the event were killed.[3] Probably there are a great many more such examples, where harsh reprisals or unlawful acts of revenge were inflicted on the German population. We know very little today about conditions prevailing from 1945 to 1947, especially in West Germany, since these actions on the part of the victors were never prosecuted. The Germans were forbidden to prosecute because of a law that is still in effect today, and the victors, naturally enough, had no particular interest in such prosecution.[4] The fact that East and Central Germany saw some dreadful excesses is somewhat more fully documented, on the other hand, since this was in the interests of the anti-Communist western powers.

The Partisan War in the East 1941-1944

Dr. jur. Karl Siegert, Professor at the University of Göttingen, drew up a legal expert report shortly after the end of World War Two, in which he showed that reprisal killings were, to a certain degree, common practice and not against international law.[5] Hence, reprisals and shootings of hostages can be considered as tactically questionable and possibly as morally reprehensible, but strictly speaking this was not against the law at that time. This should always be kept in mind when the topic at issue is the reactions of German troops in Russia and Serbia, i.e., in vast regions where a weak occupation power had to battle brutal partisans in order to facilitate the oft-disrupted flow of supplies to the eastern front. Partisan attacks began immediately following the start of the eastern war; certain partisan units deliberately let themselves be overrun, in order then to engage in sabotage behind the advancing German troops and to commit horrific atrocities against soldiers and civilians they caught unaware. Later on, partisan units as large as entire divisions were flown into the hinterland of the German troops, or smuggled in through the lines.[6]

Naturally, the data to be found in the subject literature about the numbers of partisans and the damage they caused vary widely, since there are few reliable documents about this kind of unlawful warfare and since the Soviet Union also always had a strong propagandistic interest in the historiography of partisan warfare. The most reliable data seems to be that provided by Bernd Bonwetsch,[7] who gives the numbers of partisans as follows: late 1941: 90,000; early 1942: 80,000; mid-1942: 150,000; spring 1943: 280,000; by 1944, skyrocketing to approximately half a million. These figures are based both on Soviet and on contemporaneous Reich-German sources. The damage done by the partisans, especially in the area of Byelorussia, is considerably more difficult to quantify. Wilenchik tells of impressive quantities of weapons and ammunition that were allegedly at the partisans' disposal, as well as of extensive crippling of the German supply lines through paralysis of railway lines, especially in 1944.[8] In general terms, this is confirmed by Werner.[9]

Professor Franz W. Seidler from the University of Munich is one of the few historians who try to keep a balanced view on the events of World War Two and opposes in a very scholarly way. His book on the Wehrmacht in its war against partisans is an excellent example of a thorough refutation of many myths. Castle Hill Publishers will try to publish several of Prof. Seidler's books in English editions over the next years. Translators working for fair prices as well as financial support for these projects are more than welcome. Please get in touch with us.

Regarding the numbers of German soldiers and civilians killed by partisans, Bonwetsch contrasts the claims from Soviet sources-up to 1.5 million-with those from the German side: 35,000 to 45,000,[10] which he considers to be more reliable, since allegedly the German sources would have had no reason to minimize the figures. However, he overlooks the fact that it is generally customary in war to downplay one's own losses. Seidler[11] recently published a balanced up-to-date study about the Wehrmacht's struggle in the partisan warfare, showing not only the disastrous and probably decisive effects of the partisan's attacks against German units and especially their supplies, but he proves also that most of the German reactions were totally covered by international law-although not always most far-sighted. Furthermore, he shows that those orders from higher up which broke international laws (e.g., the infamous “Kommissar order,” which might be considered morally appropriate, but politically stupid and judicially untenable) were in most cases sabotaged by the front units, and that these orders, after long-lasting and massive protest, were eventually revoked.

In a book critically discussed by the renowned German historians Andreas Hillgruber and Hans-Adolf Jacobsen, Boris Semionovich Telpuchowsky writes:

“Within three years of the war, the Byelorussian partisans eliminated approximately 500,000 German soldiers and officers, 47 Generals, blew up 17,000 enemy military transports and 32 armored trains, destroyed 300,000 railway tracks, 16,804 vehicles and a great number of other material supplies of all kinds.”[12]

The data also diverge greatly regarding the personnel (and concomitant costs) involved in the Germans' efforts to maintain security behind the frontlines: 300,000 to 600,000 persons were needed according to Soviet sources, vs. roughly 190,000 according to German sources.[10]

To what degree these data were inflated in order to glorify the partisans is not known, but there is no doubt that the policy of scorched earth[13] practiced by the Red Army in their retreat in 1941-42, together with the acts of sabotage and murder by the partisans, were the major contributing factors in the defeat of the German army in the East. The brutality with which the Red Army and especially the partisans fought, right from the start of the war and on orders from the highest echelons, was described vividly by J. Hoffmann,[14] for example, and again recently by A.E. Epifanow[15] and Franz W. Seidler[16]; A.M. de Zayas, in his study of the Wehrmacht War Crimes Bureau, also confirmed and corroborated much of the material which the Reich government had already collected even in those days to document the atrocities committed by not only the Red Army.[17] De Zayas also reports that the German wartime leaders did not resort to reprisals as a standard matter of course, but rather for the most part after carefully weighing the pros and cons. Especially in Russia, however, this could not prevent the fact that lower-ranking units, acting on the basis of their own experiences with the Soviet manner of warfare, engaged in reprisals (and revenge) not ordered or approved by higher ranks.[18] Finally, it must be noted that since July 1943 both the German army and the SS agreed to treat partisans like regular combatants, which meant for example that they would not be executed if captured, which was permitted by international law and common practice, but that they would be treated as normal POWs.[19] This is a measure whose generosity and humanity is, to my knowledge, unheard of anywhere in world history.

As we know today, the German Wehrmacht deployed in the East fought not only for the survival of the Third Reich, but after they abandoned all illusions of imperialism, they also fought for the freedom of all of Europe from Stalinism,[20] and therefore, in light of Prof. Siegert 's findings, we must observe that there was nothing unlawful and very little immoral about the merciless battle of the German security forces against unlawful Soviet partisans, even if that battle did involve draconic reprisals. If the official Soviet information about the numbers of German soldiers and/or their allies killed by partisans should be accurate, then it must be noted that reprisal killings of several millions of people (ratio 1:10) would have been theoretically justified. But even the numbers given by German authorities (some 40,000 victims) could have resulted theoretically in reprisal killings of about 400,000 civilians. It goes without saying that such numbers are horrific, and we can just be thankful that reprisal killings are forbidden nowadays and hope that the law will be observed. We must, however, ask whether such killings actually took place in those days.

Einsatzgruppen for the Fight against Partisans.

The so-called Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the SD (Security Service) were among others the units in charge of combating the partisans.[21] They started with not more than 4,000 men in summer 1941, but at the end of 1942 up to 15,000 Germans and 240,000 natives were involved,[22] an increase of manpower which indicates very well the parallel increase of partisan warfare at that time. Considering their relatively unsuccessful efforts at curbing partisan activity, we must note that these initially numerically weak troops were obviously entirely overwhelmed by their task of policing the enormous region (many hundred thousands of square kilometers), which they were in charge of and whose more remote areas were increasingly under the control of partisans.[23] Thus it appears a bit ridiculous when H. Höhne states:[24]

“Heydrich's Death envoys started their cruel adventure: 3,000 men were hunting Russia's five million Jews.”

Höhne omits to say that at the same time these troops were fighting against some 100,000 partisans. The allegations made against these troops today-namely, that, aside from their hopeless battle against the partisans, they also cooperated with many Wehrmacht soldiers to kill several million Jews as part of the Final Solution-beg the comment that, as Gerald Reitlinger says, this is absolutely unbelievable.[25]

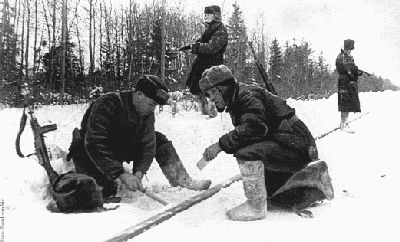

Partisans prepare to blow up a railway track leading from the West to Moscow: The delay and destruction of supplies results in the death of ten thousands of German Soldiers.

As documentary evidence for the number of Jews shot by the Einsatzgruppen behind the Russian front, the so-called event reports (Ereignisberichte) are frequently quoted. These reports are said to have been prepared by the Einsatzgruppen, who also supposedly sent them to Berlin, where these documents were found after the war. One of the most well-known experts on the subject of Einsatzgruppen, however, Hans-Heinrich Wilhelm,[26] stated as early as in 1988 that he is not certain whether or not the event reports are correct. Because he could show that the statistics in these reports about the number of murdered Jews are unreliable, he warned his colleagues as follows:[27]

“When the reliability [of these reports] in non-statistically areas is not greater, which can only be verified by comparing them with other sources from the same region, historical research would be well advised to be much more suspicious in future than it was so far when using any SS-sources.”

This remark was only consequential, since he did express similar doubts about the reliability of these documents already in his first book, when he speculated:[28]

“that here as well at least several ten thousand exterminated Jews were added to the report in order to 'improve' it, which was otherwise thought to be hardly justifiable, because the number of killed partisans was far too low.”

Elsewhere he noted that one of the event reports of the Einsatzgruppen was evidently manipulated by adding a zero to 1,134, thus turning the total to 11,034.[29] The forgers-this is what we deal with here-evidently had an interest in suggesting victim counts as high as possible. In case the Einsatzgruppen were the forgers, then one would assume that they believed that somebody in Berlin desired to see as many Jews murdered as possible. But what if someone else was the forger?

The Problem of the Event Reports in the Case of “Babi Yar”

Babi Yar is the name of an erosion ditch system in the vicinity of the Ukrainian city of Kyiv. After German troops had conquered Kyiv in September 1941, 33,771 Jews (men, women, and children) were allegedly shot in Babi Yar on September 29 and 30.

Sources for this are the Ereignismeldungen and Tätigkeits- und Lageberichte (action- and situation reports) of the Einsatzgruppen, as well as witness testimonies. Especially important is the Event Report No. 6, report time Sept. 1 to 31, 1941.[30] It states:

“The bitterness of the Ukrainian population against the Jews is exceedingly high, because they are blamed for the dynamiting of Kyiv. They are also considered the informer and agents of the NKVD, who are responsible for the terror against the Ukrainian people. All Jews were arrested as reprisal for the arson in Kyiv and a total of 33,771 Jews were executed on September 29 and 30. Money, valuables, and clothing were secured and made available to the NSV[31] for the provision of local German civilians and also partly to the temporary city administration to help needy residents.”

1. Dynamitings in Kyiv

At this point, a few explanations from established sources are necessary about the dynamiting mentioned in the above Tätigkeits- und Lagebericht. Wilhelm writes about this event:

“When in the week after the occupation [of Kyiv] several explosions caused considerable personal and material damages, this was immediately used as a welcome pretext for 'corresponding retaliatory measures' […]”[32]

Burning German supply train in the Soviet Union.

Gerald Reitlinger explains:

“On the 24th [September 1941], an enormous explosion destroyed the Hotel Continental, in which the military command of the Sixth Army was stationed. The fire spread quickly, and Blobel, who had arrived on the 21st, had to vacate his offices. 25,000 people lost their homes, and hundreds of German soldiers were killed, mostly while attempting to extinguish the flames.”[33]

German General Alfred Jodl commented about this in Nuremberg before the IMT (June 4, 1946):[34]

“Shortly before that, Kyiv had been abandoned by the Russian armies, and we had barely occupied the town when one detonation after the other occurred. The larger part of the inner city burned down. 50,000 people lost their homes. We had considerable losses, because during this fire further huge explosives blew up. The local commandant of Kyiv first thought of sabotage by local residents until we captured a detonation chart. This chart listed about 50 or 60 objects of Kyiv, which had been prepared for a long time to be blown up. This was also verified right away by the results of investigations by our pioneers. There were at least 40 such objects ready to be blasted, and most of the detonations were to be ignited remotely through radio signals.”

2. Retaliatory Action

It is therefore established that not only the inner city of Kyiv burn down as a result of these detonations-with corresponding losses of the local population-but also that the German troops lost hundreds of soldiers and almost their entire military leadership staff. Both the city's military commandant as well as the Ukrainian population first thought of sabotage. Reprisal shootings for such partisan attacks would have been the normal-and justified-reaction during wartime. Hence, these attacks did not serve “as a pretext,” as Krausnick put it.

According to the event report 97 of September 28, 1941, a “public execution of 20 Jews” was planned.[35] In the following reports no. 98 (Sept. 29), 99 (Sept. 30) and 100 (Oct. 1)-exactly on those days when the executions were to have occurred-no references to such executions can be found.

Only the event reports no. 101 of October 2 and no. 106 of October 7 report of the alleged execution of 33,771 Jews. The description by Krausnick/Wilhelm is not quite clear.[36] They do not quote these event reports-something which should be at least expected for the proof of about 34,000 murders-but a quotation from an essay by Alfred Streim of the year 1972.[37] Why did they not use the original text of these event reports-if they exist at all? The conspicuous unclear note “ibid.” in Krausnick,[38] which may refer to event report no. 101 as well as event report no. 106, cannot be considered sufficient in this case as proof for 33,771 murders.

The question whether or not the report about 33,771 shootings can be found in event report no. 101 or in event report no. 106 is not answered uniformly in the literature, which is an indication that none of the authors really checked out the sources, but that one copies always from the other. Hilberg is for event report no. 101,[39] also Klee/Dreßen/Rieß,[40] Reitlinger decided for event report no. 106,[41] as does Streim, to whom Krausnick referred.[42] By the way, Streim distanced himself completely from quoting an event report in a later work, but mentions as the only source the Tätigkeits- und Lagebericht Nr. 6 (Activity- and Situation Report no. 6).[43] Krausnick refers also to this Tätigkeits- und Lagebericht Nr. 6 for the month of October 1941.

That an event report, which among others lists individual arrests and shootings, does not report the execution of 33,771 Jews, is hard to believe, but that seems to be exactly the case.

3. Source Value and Truth of the Event Reports

The work by Krausnick/Wilhelm is the first and only thorough study about the activity of the Einsatzgruppen. The authors used as the main source for their work the Ereignismeldungen UdSSR (Event Reports USSR).[44] These event reports are only one part of a group of documents, which is labeled as follows:

- “Ereignismeldungen UdSSR des Chefs der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD” (Event Reports USSR of the Chief of the Security Police and the SD) for the period from June 23, 1941, to April 24, 1942. 194 documents survived from a total of 195.

- “Meldungen aus den besetzten Ostgebieten vom Chef der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD-Kommandostab” (Reports from the occupied eastern territories by the Chief of the Security Police and the SD command staff) for the time period of May 1, 1942, to May 21, 1943-there are 55 reports.

- “Tätigkeits- und Lageberichte der Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD in der UdSSR” (Activity- and Situation Reports of the Security Police and the SD in the USSR.)[45]

Hans-Heinrich Wilhelm declared the following about the “event reports USSR as a historic source:”[46]

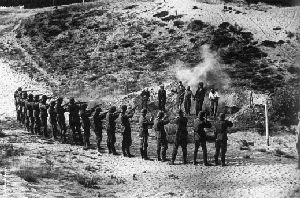

An Eye for an Eye! Top: Killed German Soldiers behind the front line, murdered by partisans; below: execution of Soviet partisans.

“These reports were received always several days later, and not three times daily or at least daily, as with military communications. Trained personnel for the preparation of these reports was not everywhere available. For the transmission via radio and telex, mostly third parties, like military units, had to be used, which caused bothersome problems due to the frequent change in location. Furthermore, the 'reporting discipline' was simply bad, and this did not change, no matter how much Heydrich fulminated. The simplest rules were not followed. For example, exact information like when and where a reported event occurred were quite frequently missing, which was unthinkable for a military report. Or the editor of the 'event reports,' who could always check back with the original notifications when in doubt, forgot to include the data from the message header into the text body, when the data received via telex was dictated to a typist, and those typed reports were left unchecked for misunderstandings and typos. Because the Einsatzgruppen and Kommandos worked at different speeds, messages frequently crossed each other or were frequently left unattended for extended periods of time because of their excessive length and low priority, some events were not only once or twice, but several times transmitted, and occasionally a backup message was sent days or weeks afterwards, it is not surprising that the editor at the RSHA[47] mixed up the chronology of events. It seems that they themselves could hardly keep an overview. Very soon, these reports were not complete anymore either. This impression quickly results when comparing, for example, the interim balances about the killing of Jews of some Einsatzkommandos, which came in on a fortnightly basis, with the corresponding individual reports about completed actions.”

The last sentence could be an attempt of an explanation, why, for example, there is evidently no event report about the alleged shooting of 33,771 Jews in Kyiv (Babi Yar)-in case that there really is no such an event report-but only a mention of the execution in the “Tätigkeits- und Lagebericht Nr. 6.”

The opinion that there does not exist an event report about these shootings is backed by the explanations of Alfred Streim, which he made during the Stuttgart Congress from May 3 to 5, 1984, about the subject “The Murder of the European Jews during the Second World War.” While talking about the murders in the Babi Yar ravine, he did not refer to an event report, but to the “summary of the executions,” i.e., to the “Tätigkeits- und Lagebericht.”[37]

The event reports were transmitted from the front via radio or telex to a department of the RSHA in Berlin. The official in charge there, who was responsible for the final written form of the reports-as they exist today-was Dr. Günther Knobloch (born 1910). During a hearing by the Central Office Ludwigsburg in 1959 Knobloch gave the following description about the preparation of the event reports and the Activity- and Situation Reports:[48]

“From the incoming flood of messages I always marked the interesting parts red and our secretaries knew exactly, in what form to bring these messages. […] It was important at that time that the messages were quite voluminous. […] Because of this I saved material from days, when we received many messages, for days with only a few messages. The messages from the individual Kommandos and Groups were always filed under these Kommandos and Groups, and an error can of course not necessarily be ruled out. […] Practically no changes in content occurred. […] I would like to add, however, that SS-Gruppenführer Müller […] frequently made handwritten changes also to the actual content. […] I also had often the impression that the information contained exaggerated events and numbers.[…]

At some time in the year 1942, we had to summarize the daily event reports in fortnightly reports, and later these were even changed to monthly reports. But it is also possible that the sequence was reverse. These summaries were prepared by me as well. […] These reports were based exclusively on the daily event reports.”

The “time in the year 1942” mentioned by Knobloch is either a printing error in the book or Knobloch remembered it wrong, since these Tätigkeits- und Lageberichte exist since June 1941, that is since the very beginning of the Russian campaign. The meaning of these summaries, however, is not clear. Why these repetitions in the Tätigkeits- und Lageberichte, which actually, as Wilhelm noticed while comparing them with the event reports, were often no repetitions but new reports?

From both Wilhelm's and Knobloch's descriptions the following can be deducted: reports from the front, prepared by non-qualified persons-some of them in double or even multiple versions-were received by the RSHA in Berlin by radio or telex, often with considerable delays. There they were reviewed by Knobloch, important parts highlighted, rewritten by secretaries and sent out unchecked and uncorrected as the final event reports. Later on, after weeks, summaries were prepared from these event reports, to which, however, new data were added while others were deleted on an unknown basis. These summaries were issued as Tätigkeits- und Lageberichte (Activity and Situation Reports).

Krausnick and Wilhelm call these reports with their dubious history “authentic” documents. According to the opinion of the same authors, this authenticity is further supported by the following:[49]

Partisan warfare during the Russian campaign. Similar pictures became well-known in America only after the U.S. Army applied similar tactics during the Vietnam war.

- they were captured by the U.S. units;

- they were cited in Nuremberg in all relevant trials;

- no defense lawyer ever seriously attempted to question their authenticity;

- the editors who were responsible within the RSHA for their preparation as well as numerous recipients of the report at that time did identify them.

Regarding #4, the responsible report editor Knobloch testified the following, when photo copies of these reports were submitted to him in Ludwigsburg:[50]

“The photocopies of the reports submitted to me can be considered as the event reports issued at that time in regards to their form.”

“In regards to their form”-Knobloch said either nothing about their content or we are not told about it!

Although the above mentioned points made by Krausnick and Wilhelm do in no way prove the authenticity of the submitted documents, they still could be authentic. However the problem in this case is that the events reported in these presumably authentic documents are evidently incongruent with reality, as is clear from the descriptions of Wilhelm and Knobloch.

4. Were 33,771 Jews Murdered?

The question of how many Jews were murdered in those two days in Babi Yar is controversial in the literature. Hilberg writes that “the success of the Kyiv action is difficult to evaluate.”[51] According to event report no. 97 of Sept. 9, 1941, 50,000 Jews were intended for the shooting, but then 33,771 were reported. However, Paul Blobel, the leader of the Sonderkommando 4a, which was responsible for executions, maintained later in Nuremberg that no more than 16,000 were shot.[52] As a matter of fact, event report no. 97 announced also that the city commandant recommended the public execution of 20 Jews.[35] The Soviet document USSR-9, which was submitted during the main trial in Nuremberg, even states that more than 100,000 men, women, children, and elderly people were shot in Babi Yar.[53] This number, however, was not mentioned anywhere else.

The number generally agreed upon seems to be 33,771. Krausnick maintains that this number was “reported several times,”[54] namely in an event report, which he does not specify, and in the Tätigkeits- und Lagebericht no. 6. This would, of course, mean that this number was not reported several times, but maybe only once, and that it was then repeated in a transcript!

Reitlinger also quotes event reports and action reports, but he confuses their names. When talking about “Activity Reports,” he actually refers to event reports and vice versa. He also claims that the number of 33,771 is verified, because the “activity report no. 106 and the event report No. 6 both contain the same number 33,771.”[55] Here a transcript of a report is also supposed to confirm the report itself. It is doubtful whether Reitlinger has even seen “event report no. 106,” which he mentions only in his text, because if he had, he probably would have quoted the document correctly.

For Wolfgang Benz the “number of the murdered” (33,771) “is also corroborated by testimonies of perpetrators, spectators, and several survivors of the massacre.”[56] Herbert Tiedemann reported extensively about the completely chaotic, arbitrary picture, which those alleged 'witnesses' and other reporters drew about Babi Yar, and he has shown that these testimonies can in no way be accepted as proof for anything.[57]

But how could such a number erroneously slip into the reports? Could multiple reports about the same event and typos have led to it? The exact process of this possible number explosion can probably not be reconstructed.

There is, however, at least one example for a similar miracle of numbers in the reports of the Einsatzgruppen, which Wilhelm discovered. In a report of the outpost Dünaburg of the Commander of Security Police in Latvia dated Nov. 11, 1941, a number of 1,134 murdered Jews is mentioned. In a summary report of February 1942, the same number was-by typo?-inflated to 11,034.[58] A zero changed one thousand to ten thousand. However, Wilhelm thinks that the latter number is the correct one, because this number is also mentioned in an undated report of Einsatzgruppe A.[59]

In conclusion it can be said that a critical investigation of the documents referred to here has still to be done, not least in order to determine what their exact content is.[60] But based upon known information about the history and origin of these documents, it can concluded that the Ereignismeldungen (event reports) and the Tätigkeits- und Lageberichte (activity and situation reports), even if they are authentic, do-according to scientific standards-not conclusively prove the reality of the event described in them. For this, other and qualitatively better evidence has to be presented.

5. Certainty Derives from Material Evidence and Unsuspicious Documents only

As a result of the discovery of air photos, we are in the fortunate position to prove beyond reasonable doubt that this alleged mass murder did at least not occur at that claimed location.[61] These pictures of Babi Yar, taken by German reconnaissance planes between 1939 and 1943, prove that this ravine never underwent any noticeable topographic changes, and by a lucky coincidence, a German reconnaissance air plane even made pictures of this area exactly at a time when-according to eye witnesses-the corpses of all the murdered Jews were allegedly exhumed from their mass graves and supposedly cremated on gigantic pyres. Nothing of this is shown on these pictures.

The following is a translation of one page of a German wartime report on their fight against partisans. the original of the document is depicted to the right. Click on the icon to the right to view the German original.

| The Reichsführer-SS | Field-Command Post December 29, 1942 |

| Subject: | Reports to the Führer about |

| Combat against Bandits. | |

| R e p o r t No. 61 | |

| Russia-South, Ukrain, Bialystok. | |

| Success of Combat against Bandits from Sept. 1 to Dec. 12, 1942 |

| 1.) Bandits: | ||||

| a) Confirmed Deaths after Combats (x) | ||||

| August: | September: | October: | November: | Total: |

| 227 | 381 | 427 | 302 | 1337 |

| b) Prisoner immediately executed | ||||

| 125 | 282 | 87 | 243 | 737 |

| c) Prisoners executed after thorough interrogation | ||||

| 2100 | 1400 | 1596 | 2731 | 7828 |

| 2.) Bandit associates and bandit suspects | ||||

| a) Arrested | ||||

| 1343 | 3078 | 8337 | 3795 | 16553 |

| b) Executed | ||||

| 1198 | 3020 | 6333 | 3706 | 14257 |

| c) Jews executed | ||||

| 31246 | 165282 | 95735 | 70948 | 363211 |

| 3.) Renegades because of German Propaganda | ||||

| 21 | 14 | 42 | 63 | 140 |

| (x) Since the Russians carry off or immediately bury their killed soldiers, the losses are much higher, even according to statements of prisoners. | ||||

Another example of a sensational discovery which was not reported by the mainstream media has a similarly devastating effect upon the thesis of Goldhagen & Co: In the summer of 1996, the city of Marijampol in Latvia decided to erect a memorial in memory of the tens of thousands of Jews who were allegedly murdered by the Einsatzgruppen. In order to erect it at the proper place, an attempt was made to locate the exact position of the mass graves. Excavations were therefore carried out at those locations which were identified by witnesses, but-oh wonder-Not a single trace of any mass graves could be found.[63] Further excavations in the vicinity of the alleged locations of mass murder did not result in anything else but untouched virgin soil either.[64] Did 'the Germans' commit the perfect crime by succeeding to completely hide all traces of their mass murder and even restore the soil to its original layering? Could they commit evil wonders after all? Or were the witnesses wrong?[65]

Causes of the East-European Anti-Semitism

Does this mean, that no Jew was ever shot by the SS in the east, the German Wehrmacht, or the Einsatzgruppen? Of course not. It is undeniable that German military units shot numerous civilians behind the front in connection with the “Bandenkämpfe” (combats against partisans), especially in the form of reprisal killings.[66] During the war in the east, which was fought with extreme brutality, it is furthermore likely that reprisal-excesses occurred occasionally, that is, where not only partisans and their supporters as well as criminal elements (and possibly also POW's) were killed as reprisals in accordance with international law, but that it also came to killings of innocent civilians with no connection to reprisals. If this would not have happened on the German side, the German army would be the first in the history of mankind who would consist only of angels, which can be ruled out.

Obviously, in selecting the victims of such reprisals, one would not choose Ukrainians, Byelorussians or members of the Balkan, Baltic or Caucasian peoples, of whom considerable numbers fought in German units. The fact that the Jews were predominantly unpopular amongst these peoples was mainly due to fairly recent causes. In the previous decades many people had had terrible experiences with Communist commissars, disproportionately many of whom were of Jewish descent, especially in the first few decades of Soviet Bolshevism. The Russian Jewess Sonja Margolina has made some interesting points regarding the involvement of the Russian Jews in the Bolshevist reign of terror:[67]

“Nevertheless: the horrors of revolution and civil war, just like those of the repressions later, are closely tied to the image of the Jewish commissar.” (p. 47)

“The Jewish presence in the instruments of power was so impressive that even such an unbiased contemporaneous researcher as Boris Paramonov, a Russian cultural historian living in New York, asked whether the promotion of the Jews into leadership positions may perhaps have been a 'gigantic provocation'.” <(p. 48)

Margolina has written a particularly detailed analysis of a book which appeared in 1924 under the title Rußland und die Juden. This book examines the causes of the Russian Jews' conspicuously above-average participation in the excesses of the October Revolution and the dictatorship that followed it, and analyzed the consequences of this involvement. In their appeal “To the Jews in all nations!” the authors of this book discussed by Margolina wrote:

“'The Jewish Bolsheviki's overeager participation in the subjugation and destruction of Russia is a sin that already bears within itself the seeds of its retribution. For what greater misfortune could happen to a people than to have its own sons engage in excesses. Not only will this be counted against us as an element of our guilt, it will also be held up to us as reproach for an expression of our power, for a striving for Jewish hegemony. Soviet power is equated with Jewish power, and the grim hatred of the Bolsheviki will transform into a hatred of the Jews […] All nations and peoples will be swamped by waves of Judeophobia. Never before have such thunderclouds gathered above the heads of the Jewish people. This is the bottom line of the Russian upheaval for us, for the Jewish people.'” (p. 58)

Margolina quotes further from this anthology:

“'The Russians have never before seen a Jew in power, neither as governor nor as policeman, nor as postal official. There were both good and bad times in those days too, but the Russian people lived and worked and the fruits of their labors were their own. The Russian name was mighty and threatening. Today the Jews are at every corner and in all levels of power. The Russians see them at the head of the Czarist city, Moscow, and at the head of the metropolis on the River Neva and at the head of the Red Army, the ultimate mechanism of self-destruction. […] The Russians are now faced with a Jew as judge as well as executioner; they encounter Jews at every step, not Communists who are just as poor as they themselves but who nevertheless give orders and take care of the interests of the Soviet power […] It is not surprising that the Russians, in comparing the past to the present, conclude that the present power is Jewish, and so bestial precisely because of that.'” (p. 60)

In the early 1990s, Professor Dr. Ernst Nolte also pointed out the Jews' intimate entanglement in Communism, though naturally he rejects equating the Jews with Bolshevism. Nolte writes:[68]

“For readily apparent social reasons, was not the per-centage of persons of Jewish extraction particularly great among the participants in the Russian Revolution, different from the percentages of other minorities such as the Latvians? Even at the start of this century Jewish philosophers were still pointing with great pride to this extensive participation of the Jews in Socialist movements. After 1917, when the anti-Bolshevist movement-or propaganda-stressed the topic of the Jewish People's commissars above all others, this pride was no longer expressed, […] But it took Auschwitz to turn this topic into a taboo for several decades.

It is all the more remarkable that in 1988 the publication Commentary, the voice of right-wing Jews in America, published an article by Jerry Z. Muller who recalls these indisputable facts-though of course they are open to interpretation:

'If Jews were highly visible in the revolution in Russia and Germany, in Hungary they seemed omnipresent. […] Of the government's 49 commissars, 31 were of Jewish origin […] Rakosi later joked that Garbai (a gentile) was chosen for his post 'so that there would be someone who could sign the death sentences on Saturdays'. […] But the conspicuous role of Jews in the revolution of 1917-19 gave anti-Semitism (which 'seemed on the wane by 1914') a whole new impetus. […] Historians who have focused on the utopian ideals espoused by revolutionary Jews have diverted attention from the fact that these Communists of Jewish origin, no less than their non-Jewish counterparts, were led by their ideals to take part in heinous crimes-against Jews and non-Jews alike.'”

Referring to the causal nexus Nolte had postulated between GULag and Auschwitz, Muller concludes:

“The Trotskies make the revolutions [i.e., the GULag] and the Bronsteins pay the bills [in the Holocaust].”[69]

Thus it seems understandable that National Socialism, and the eastern peoples fighting alongside for their freedom, equated the Jews in general with the Bolshevist terror and the activities of the commissars-though such an identification, being sweeping and collective, was unjust. Nevertheless, it is therefore more than plausible that it was Jews, first and foremost, who were made to pay for the partisan warfare and other war crimes of the Soviets. Anyone who (rightly) criticizes this, however, should also not omit to consider where the blame for this kind of escalation of the war in the East was to be found. And clearly it was to be found with Stalin who, as an aside, had treated the Jews in his sphere of influence at least as mercilessly ever since the war had begun, as Hitler had.[70]

Notes

First published as “Partisanenkrieg und Repressaltötungen” in Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung 3(2) (1999), pp. 145-153. Translated by Fabian Eschen. All but one picture reproduced in this article were taken from the book Die Wehrmacht im Partisanenkrieg by Franz W. Seidler (Pour le Merite, Selent 1998).

| [1] | Just recently, this exhibition has come to the U.S. as well, in a slightly revised version; cf. Johannes Heer, Klaus Naumann (ed.), Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941-1944, Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 1995; Klaus Sojka (ed.), Die Wahrheit über die Wehrmacht. Reemtsmas Fälschungen widerlegt, FZ-Verlag, Munich 1998; Franz W. Seidler, Verbrechen an der Wehrmacht, Pour le Mérite, Selent 1998; Bogdan Musial, “Bilder einer Ausstellung. Kritische Anmerkungen zur Wanderausstellung 'Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941-1944,'” Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, 47(4) (1999), pp. 563-591; Krisztián Ungváry, “Echte Bilder – problematische Aussagen,” Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, 50(10), (1999), pp. 584-595; Klaus Hildebrandt, Hans-Peter Schwarz, Lothar Gall, cf. “Kritiker fordern engültige Schließung,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Nov. 6, 1999, p. 4; Ralf Georg Reuth, “Endgültiges Aus für Reemtsma-Schau?,” Welt am Sonntag, Nov. 7, 1999, p. 14; Walter Post, Die verleumdete Armee, Pour le Mérite, Selent 1999. |

| [2] | hoh, “Die Franzosenzeit hat begonnen,” Stuttgarter Zeitung, 25.4.1995 |

| [3] | Cf. Heinrich Wendig, Richtigstellungen zur Zeitgeschichte, issue 8, Grabert, Tübingen 1995, p. 46. In fact, this has not been a reprisal, but merely a mass murder; cf. also ibid., issue 2 (1991), pp. 47ff.; issue 3 (1992), pp. 39ff.; issue 10 (1997), pp. 44f. |

| [4] | One exception is a recently publicized case of the unwarranted murder of 48 German soldiers who had already surrendered: Michael Sylverster Kozial, “US-Kripo ermittelt nach 51 Jahren,” Heilbronner Stimme, September 24, 1996; “Später Fahndung nach Mördern in US-Uniform,” Stuttgarter Zeitung, September 27, 1996, p. 7. |

| [5] | Prof. Dr. jur. Karl Siegert, Repressalie, Requisition und höherer Befehl, Göttinger Verlagsanstalt, Göttingen 1953, 52 pp; English translation: Ernst Siegert, “Reprisals and Orders from Higher up,” in: G. Rudolf (ed.), Dissecting the Holocaust, 2nd ed., Theses & Dissertations Press, Chicago, IL, 2003, pp. 530-550. |

| [6] | Relevant orders were issued by Stalin and were broadcast via all Soviet Russian stations; cf. Keesing's Archiv der Gegenwart, 1941, July 3rd + 21st 1941; cf. Sowjetski Partisani, Moscow 1961, p. 326. |

| [7] | Bernd Bonwetsch, “Sowjetische Partisanen 1941-1944,” in Gerhard Schulz (ed.), Partisanen und Volkskrieg, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1985, pp. 99, 101. |

| [8] | Witalij Wilenchik, “Die Partisanenbewegung in Weißrußland,” in Hans Joachim Torke (ed.), Forschungen zur osteuropäischen Geschichte, v. 34, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1984, pp. 280f., 285, 288f. This chapter has a certain anti-Fascist undertone. |

| [9] | S. Werner, Die 2. babylonische Gefangenschaft, originally self-published by author, Pfullingen 1990; 2nd ed. Grabert, Tübingen 1991, pp. 88-93 (online: vho.org/D/d2bg/I_II.html); English online only (vho.org/GB/Books/tsbc). |

| [10] | B. Bonwetsch, op.cit. (note [7]), pp. 111f. |

| [11] | Franz. W. Seidler, Die Wehrmacht im Partisanenkrieg, Pour le Mérite, Selent 1998; cf. Hans Poeppel (ed.), Die Soldaten der Wehrmacht, 3rd ed., Herbig, Munich 1999. |

| [12] | B.S. Telpuchowski, Die Geschichte des Grossen Vaterländischen Krieges 1941-1945, Bernard & Graefe Verlag für Wehrwesen, Frankfurt/Main 1961, p. 284; comparable Seidler, op. cit. (note [11]), p. 36f.; similar data may also be found in Heinz Kühnreich, Der Partisanenkrieg in Europa 1939-1945, Dietz, Berlin (East) 1965; for further interesting information, see I.I. Minz, I.M. Rasgon, A.L. Sidorow, Der Große Vaterländische Krieg der Sowjetunion, SWA Verlag, Berlin 1947; it is said that the Washington National Archive's document copies regarding partisan warfare in the former Soviet Union have recently been made unavailable to the public. This information and the preceding references are courtesy of Fritz Becker; cf. also Becker, “Stalins völkerrechtswidriger Partisanenkrieg,” Huttenbriefe 15(4) (1997), pp. 3-6 (online: vho.org/D/Hutten/Becker15_4.html). |

| [13] | Cf. Walter N. Sanning, “Soviet Scorched-Earth Warfare,” in The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 6/No. 1, Spring 1985, pp. 92-116 (online (German): vho.org/D/DGG/Niederreiter29_1.html). |

| [14] | J. Hoffmann, Stalin's War of Extermination 1941 – 1945, Theses & Dissertations Press, Capshaw, AL, 2001, pp. 305-327. |

| [15] | A.E. Epifanow, H. Mayer, Die Tragödie der deutschen Kriegsgefangenen in Stalingrad von 1942 bis 1956 nach russischen Archivunterlagen, Biblio, Osnabrück 1996. |

| [16] | Franz W. Seidler, Verbrechen an der Wehrmacht, Pour le Mérite, Selent 1998, pp. 5f. (online: vho.org/D/ vadw/vadw.html); English in preparation. |

| [17] | A. de Zayas, Die Wehrmachtsuntersuchungsstelle, 4th ed., Ullstein, Berlin 1984, passim., esp. pp. 273-307. |

| [18] | Ibid., pp. 198-23. |

| [19] | Franz W. Seidler, op. cit. (note 6), p. 127 |

| [20] | Cf. J. Hoffmann, “Die Sowjetunion bis zum Vorabend des deutschen Angriffs,” in Horst Boog et al., Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg, vol. 4: Der Angriff auf die Sowjetunion, 2nd ed., Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1987; Hoffmann, “Die Angriffsvorbereitungen der Sowjetunion,” in B. Wegner (ed.), Zwei Wege nach Moskau, Piper, Munich 1991; V. Suvorov, Icebreaker: Who Started the Second World War?, Hamish Hamilton, London 1990; Suvorov, Der Tag M, Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1995; E. Topitsch, Stalin 's War: A Radical New Theory of the Origins of the Second World War, Fourth Estate, London 1987; cf. W. Post, Unternehmen Barbarossa, Mittler, Hamburg 1995; F. Becker, Stalins Blutspur durch Europa, Arndt Verlag, Kiel 1996; Becker, Im Kampf um Europa, 2nd ed., Leopold Stocker Verlag, Graz/Stuttgart 1993; W. Maser, Der Wortbruch. Hitler, Stalin und der Zweite Weltkrieg, Olzog Verlag, Munich 1994. |

| [21] | For more detaisl about this combat cf. F. W. Seidler, op. cit. (note [11]), pp. 69-132. |

| [22] | Cf. H. Höhne, Der Orden unter dem Totenkopf, Bertelsmann, Munich 1976, pp. 328, 339; cf. H. Krausnick, H.-H. Wilhelm, Die Truppe des Weltanschauungskrieges. Die Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD 1938-1942, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1981, p. 147, cf. p. 287; Richard Pemsel, Hitler – Revolutionär, Staatsmann, Verbrecher?, Grabert, Tübingen 1986, pp. 403-407. |

| [23] | For more information about the partisan warfare cf., e.g., Erich Hesse, Der sowjetrussische Partisanenkrieg 1941-1944 im Spiegel deutscher Kampfanweisungen und Befehle, 2nd ed., Muster-Schmidt, Göttingen 1992; John A. Armstrong (ed.), Soviet Partisans in World War II, Univ. of Wisc. Press, Madison, Wisc., 1964; Tomas Nigel, Partisan Warfare 1941-1945, Osprey, London 1983. |

| [24] | H. Höhne, op. cit. (note [22]), p. 330. |

| [25] | G. Reitlinger, Die SS, Tragödie einer deutschen Epoche, Desch, Munich 1957, p. 186; similar Efraim Zuroff, Beruf: Nazijäger. Die Suche mit dem langen Atem: Die Jagd nach den Tätern des Völkermordes, Ahriman, Freiburg 1996, p. 44, were he says that 3,000 men, “mobil killing units, whose task was to kill all Jews and communist officials in the area occupied by the Wehrmacht.” This included the huge area “from the suburbs of Leningrad in the north to the Asov sea in the south.[…] Their weapons were conventional firearms. Nevertheless they succeeded in killing 900,000 Jews in 15 months.” Zuroff wonders, but he has no doubts. This has been possible, according to Zuroff, because of the “fanatic support by the native population.” (p. 47) That there has been a massive partisan warfare in the back of the fighting German army is either unknown to Zuroff or he is not interested in it. |

| [26] | Together with Helmut Krausnick co-author of the famous book Die Truppe des Weltanschauungskrieges, (The Troop of the War of Ideology) op. cit. (note 17). |

| [27] | H.-H. Wilhelm, lecture during an international history conference at the university Riga, September 20-22, 1988, p. 11. Based on this recital Wilhelm wrote the article “Offene Fragen der Holocaust-Forschung” (Open Question about the Holocaust Research) in U. Backes, E. Jesse, R. Zitelmann (ed.), Die Schatten der Vergangenheit, Propyläen, Berlin 1992 S. 403, which however does not contain this section. I obtained this information from Costas Zaverdinos, who had the manuscript of Wilhelms Riga lecture and who reported about this during the opening speech of the history conference on April 4, 1995 at the university of Natal, Pietermaritzburg. |

| [28] | H.-H. Wilhelm, op. cit. (note 17), p. 515. |

| [29] | Ibid., p. 535. |

| [30] | Document R-102 in Der Prozeß gegen die Hauptkriegsverbrecher vor dem Internationalen Militärgerichtshof, (IMT), vol. 1 – XXXXII, Nürnberg 1947-1949, here vol. XXXVIII, 279-303, here p. 292f. |

| [31] | Nationalsozialistischen Volkswohlfahrt, National Socialist People's Welfare |

| [32] | H. Krausnick, H.-H. Wilhelm, op. cit. (note 17), p. 189. |

| [33] | Gerald Reitlinger, Die Endlösung. Hitlers Versuch der Ausrottung der Juden Europas 1939-1945, Colloquium Verlag, Berlin 41961, p. 262. |

| [34] | IMT, XV, p: 362; vol. XV, p. 363: “Es waren ganze Stäbe in Kiew […] in die Luft geflogen.” |

| [35] | H. Krausnick, H.-H. Wilhelm, op. cit. (note 17), p. 189, Fn 161. |

| [36] | Ibid., p. 190. |

| [37] | Alfred Streim, “Zum Beispiel: Die Verbrechen der Einsatzgruppen in der Sowjetunion,” in: Adalbert Rückerl (Hrsg.), NS-Prozesse. Nach 25 Jahren Strafverfolgung. Möglichkeiten – Grenzen – Ergebnisse, C.F. Müller, Karlsruhe 1972. |

| [38] | H. Krausnick, H.-H. Wilhelm, op. cit. (note 17), p. 190, note. 164, all sources are otherwise exactly quoted. |

| [39] | Raul Hilberg, Die Vernichtung der europäischen Juden. Die Gesamtgeschichte des Holocaust, Olle & Wolter, Berlin 1982, p. 213, FN 59. |

| [40] | Ernst Klee, Willi Dreßen, Volker Rieß (Hg.), “Schöne Zeiten.” Judenmord aus der Sicht der Täter und Gaffer, S. Fischer, Frankfurt/M. 1988, S. 69. |

| [41] | Op. cit. (note 27), p. 263. |

| [42] | Op. cit. (note 31), p. 86f. |

| [43] | Alfred Streim, “Zur Eröffnung des allgemeinen Judenvernichtungsbefehls gegenüber den Einsatzgruppen,” in: Eberhard Jäckel, Jürgen Rohwer (Hg.), Der Mord an den Juden im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Entschlußbildung und Verwirklichung, Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1985, S. 114. |

| [44] | H. Krausnick, H.-H. Wilhelm, op. cit. (note 17), p. 336. |

| [45] | Ibid., p. 649. |

| [46] | Ibid., p. 335f. |

| [47] | Reichssicherheitshauptamt, Reich Security Main Office. |

| [48] | H. Krausnick, H.-H. Wilhelm, op. cit. (note 17), p. 337f. |

| [49] | Ibid., p. 335. |

| [50] | Ibid., p. 338. |

| [51] | Op. cit. (note 33), p. 227, note145 |

| [52] | Affidavit of 6.6.1947, NO-3824. |

| [53] | See IMT, VII, S. 612. |

| [54] | Op. cit. (note 17), p. 190. |

| [55] | Op. cit. (note 27), p. 263. |

| [56] | Wolfgang Benz (Hrsg.), Legenden, Lügen, Vorurteile, dtv, München 1990, p. 40. |

| [57] | “Babi Jar: Kritische Fragen und Anmerkungen,” in: Ernst Gauss (Ed.), Grundlagen zur Zeitgeschichte, Grabert, Tübingen 1994, p. 375-399. |

| [58] | Op. cit. (note 17), p. 535. |

| [59] | IMT, vol. XXX, S. 74. |

| [60] | U. Walendy pointed out that these reports could not possibly be designated as documents: no letter head, no signature, no file number or letter-diary number. It is simply a piece of paper written on it: U. Walendy, “Babi Jar – Die Schlucht 'mit 33.771 ermordeten Juden'?,” Historische Tatsachen Nr. 51, Verlag für Volkstum und Zeitgeschichtsforschung, Vlotho 1992, p. 21, as usual written with a 'hot' pen, but still a good starting point; see also: Historische Tatsache Nr. 16 & 17, “Einsatzgruppen im Verband des Heeres,” parts 1 & 2, ibid., 1983. |

| [61] | See J.C. Ball, Air Photo Evidence, Ball Recource Services Ltd., Delta B.C., 1992; ders., in: E. Gauss (Hg.), Grundlagen zur Zeitgeschichte, Grabert, Tübingen, S. 235-248.; vgl. H. Tiedemann, ibid., p. 375-399. |

| [62] | From: G. Fleming, Hitler and the Final Solution, University of California Press, Berkeley 1984, ill. 6, pp. 92f. (source: The Nizkor Project: www.nizkor.org/ftp.cgi/orgs/german/einsatzgruppen/images/ |

| [63] | Lietuvos Rytas (Latvian news paper), August 21,1996. |

| [64] | Personal message from Dr. M. Dragan. |

| [65] | I will not elaborate here on the equally problematic gas wagons allegedly also utilized by the Einsatzgruppen; see Ingrid Weckert in E. Gauss (Ed.), op. cit. (note 50), p. 193-218. |

| [66] | For the time between Jan. 1, 1943, and Oct. 31, 1944 (22 months), the German authorities have claimed 145,364 persons killed in the partisan warfare, 88,493 imprisoned, and 90,993 civilians “registered,” i.e., either sent into camps or otherwise punished; cf. F. W. Seidler, op. cit. (note [12]). |

| [67] | S. Margolina, Das Ende der Lügen, Siedler, Berlin 1992. |

| [68] | E. Nolte, “Abschließende Reflexionen über den sogenannten Historikerstreit,” in U. Backes, E. Jesse, R. Zitelmann (eds.), Die Schatten der Vergangenheit, Propyläen, Berlin 1992, pp. 83-109, here pp. 92f. |

| [69] | J.Z. Muller, “Communism, Anti-Semitism and the Jews,” in Commentary, issue 8, 1988, pp. 28-39; for a more ideological approach to National Socialist anti-Semitism cf. Erich Bischoff, Das Buch vom Schulchan aruch, Hammer Verlag, Leipzig 1929; on this expert opinion one of the best known National Socialist anti-Semites, Theodor Fritsch, relied heavily: T. Fritsch, Handbuch zur Judenfrage, 31st ed., Hammer-Verlag, Leipzig 1932; a comparison to modern Jewish critics of Judaism is extremely revealing, cf. Israel Shahak, Jewish History, Jewish Religion, Pluto Press, London 1994 (online: codoh.com/zionweb/zishahak/zishahakan01.html). |

| [70] | Regarding the question of the involvement of Jews in the soviet partisan warfare against German troops cf. E. Jäckel, P. Longerich, J. H. Schoeps (eds.), Enzyklopädie des Holocaust, Argon, Berlin 1993, p. 1348; cf. Nechama Tec, Defiance, the Bielski Partisans, Oxford University Press, New York 1993. |

Bibliographic information about this document: The Revisionist 1(3) (2003), pp. 321-330.

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: First published in German as "Partisanenkrieg und Repressaltötungen" in "Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung," 3(2) (1999), pp. 145-153