The 1945 Sinkings of the Cap Arcona and the Thielbek

Allied Attacks Killed Thousands of Concentration Camp Inmates

All prisoners of German wartime concentration camps who perished while in German custody are routinely regarded as “victims of Nazism” – even if they lost their lives as direct or indirect result of Allied policy. Similarly, all Jews who died in German captivity during World War II – no matter what the cause of death – are counted as “victims of the Holocaust.”

This view is very misleading, if not deceitful. In fact, many tens of thousands of camp inmates and Jews lost their lives as direct and indirect victims of Allied action, or of the horrors of the Second World War. For example, the many thousands of Jews who perished in the notorious Bergen-Belsen camp during and after the final months of the war in Europe, including Anne Frank, were primarily victims not of German policy, but rather of the turmoil and chaos of war.

Among the German concentration camp prisoners who perished at Allied hands were some 7,000 inmates who were killed during the war’s final week as they were being evacuated in three large German ships that were attacked by British war planes. This little-known tragedy is one of history’s greatest maritime disasters.

The Cap Arcona, launched in May 1927, was a handsome passenger ship of the “Hamburg-South America” line. At 27,000 gross registered tons, it was the fourth-largest ship in the German merchant marine. For twelve years – until the outbreak of war in 1939 – she had sailed regularly between Hamburg and Rio de Janeiro. In the war’s final months she was pressed into service by the German navy to rescue refugees fleeing from areas in the east threatened by the Red Army. This was part of a vast rescue operation organized by the German navy under the supervision of Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz. All but unknown in the United States today, this great undertaking saved countless lives. The Thielbek, a much smaller ship of 2,800 gross registered tons, was also used to transport refugees as part of the rescue operation.

In April 1945, Karl Kaufmann, Gauleiter of Hamburg and Reich Commissioner for merchant shipping, transferred the Cap Arcona and the Thielbek from naval command, and ordered them to Neustadt Bay in the Baltic Sea near the north German city of Lübeck.

Some 5,000 prisoners hastily evacuated from the Neuengamme concentration camp (a few miles southeast of Hamburg) were brought on board the Cap Arcona between April 18 and 26, along with some 400 SS guards, a naval gunnery detail of 500, and a crew of 76. Similarly the Thielbek took on some 2,800 Neuengamme prisoners. Under the terrible conditions that prevailed in what remained of unoccupied Germany during those final weeks, conditions for the prisoners on board the two vessels were dreadful. Many of the tightly packed inmates were ill, and both food and water were in very short supply.

On the afternoon of May 3, 1945, British “Typhoon” fighter-bombers, striking in several attack waves, bombarded and fired on the Cap Arcona and then the Thielbek. The two ships, which had no military function or mission, were flying many large white flags. “The hoisting of white flags proved useless,” notes the Encyclopedia of the Third Reich. The attacks were thus violations of international law, for which – if Britain and not Germany had been the vanquished power – British pilots and their commanders could have been punished and even executed as “war criminals.”

The Thielbek, struck by rockets, bombs and machine gun fire, sank in just 15-20 minutes. British planes then fired on terror-stricken survivors who were struggling in rescue boats or thrashing in the cold sea. Nearly everyone on board the Thielbek perished quickly, including nearly all the SS guards, ship’s officers and crew members. Only about 50 of the prisoners survived.

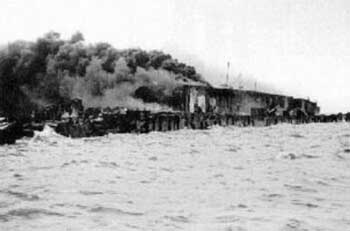

The burning Cap Arcona took longer to go under. Many inmates burned to death. Most of those who were able to leap overboard drowned in the cold sea, and only some 350-500 could be rescued. During the next several days hundreds of corpses washed up on nearby shores, and were buried in mass graves. Having sunk in shallow water, the wreck of the capsized Cap Arcona remained partially above water as a grim reminder of the catastrophe.

A German reference work, Verheimlichte Dokumente, sums up:

A particularly barbaric Allied war crime was the bombing on May 3, 1945, by British Royal Air Force planes of the passenger ships Cap Arcona and Thielbek in the Lübeck bay, packed with concentration camp inmates. Among the many ‘nameless’ victims were many prominent political figures, a fact that is hushed up today because the fact that concentration camp inmates, many of them resistance fighters against Hitler, perished as victims of the terror of the ‘liberators’ does not conform to the portrayal of the ‘reeducators’.

Another reference work, Der Zweite Weltkrieg (1985), notes:

A unique tragedy is the end on May 3, 1945, of the ‘Hamburg-South’ passenger steamship Cap Arcona and the steamship Thielbek, both carrying concentration camp prisoners on board who believed that they were saved, but who were now bombed in the Neustadt Bay by Allied air planes. On the Cap Arcona alone, more than 5,000 perished – ship personnel, concentration camp inmates, and SS guards.

The deaths on May 3, 1945, of some 7,000 concentration camp prisoners – victims of a criminal British attack – remains a little-known chapter of World War II history. This is all the more remarkable when one compares the scale of the disaster with other, much better known maritime catastrophes. For example, the well-known sinking of the great British liner Titanic on April 15, 1912, took “only” 1,523 lives.

Actually, among the greatest naval disasters in history are the Baltic Sea sinkings of three other German vessels by Soviet submarines in the first half of 1945: the Wilhelm Gustloff, on January 30, 1945, with the loss of at least 5,400 lives, mostly women and children; the General Steuben on February 10, 1945, with the loss of 3,500, mostly refugees and wounded soldiers; and, above all, the Goya on April 16, 1945, taking the lives of some 7,000 refugees and wounded soldiers.

Sources: Fritz Brustat-Naval, Unternehmen Rettung (Herford: Koheler, 1970), pp. 197-201; C. Zentner & F. Bedürftig, eds., The Encyclopedia of the Third Reich (New York: Da Capo, 1997), pp. 126, 644-645, 952; W. Schütz, Hrsg., Lexikon: Deutsche Geschichte im 20. Jahrhundert (Rosenheim: DVG, 1990), pp. 66, 455; Dr. Bernhard Steidle, Hrsg., Verheimlichte Dokumente, Band 2 (Munich: 1995), pp. 212, 230; “Britische RAF mordete Tausende KZ-Häftlinge,” National-Zeitung (Munich), May 19, 2000, p. 11; Kay Dohnke, “5 Minuten, 50 Meter, 50 Jahre: Gedenken an die Cap Arcona, nach einem halben Jahrhundert,” taz: die tageszeitung (Hamburg Ausgabe), May 3, 1995, also on line at http://www.theo-physik.uni-kiel.de/~starrost/akens/texte/diverses/arcona.html; “The Cap Arcona, the Thielbek and the Athen,” on line at http://www.rrz.uni-hamburg.de/rz3a035/arcona.html; Konnilyn G. Feig, Hitler’s Death Camps (New York: 1981), p. 214; Martin Gilbert, The Holocaust (New York: 1986), p. 806; M. Weber, “Bergen-Belsen: The Suppressed Story,” May-June 1995 Journal of Historical Review, pp. 23-30; M. Weber, “History’s Little-Known Naval Disasters,” March-April 1998 Journal, p. 22.

For further reading, these books are available: Rudi Goguel, Cap Arcona (Frankfurt/Main: Röderberg, 1972); Günter Schwarberg, Angriffsziel Cap Arcona (Hamburg: Stern-Buch, 1983/ Göttingen: Steidi, 1998), with portions on line at http://www.reger-online.de/buchcd/w7506002.htm; Wilhelm Lange, Cap Arcona: Dokumentation (Eutin: Struve, 1988).

“By writing yau learn how to write.”

—Latin proverb

“May yaur life be filled with lawyers.”

—Mexican curse

CODOH Comments: see also http://theesotericcuriosa.blogspot.com/2012/11/the-esoteric-miscellanea-sustenance-for_12.html and http://cruiselinehistory.com/the-ss-cap-arcona-the-nazi-titanic-and-one-of-the-worst-maritime-disasters-of-all-time/, from which some of the illustrations were taken.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 19, no. 4 (July/August 2000), pp. 2f.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a