The Strange Case of John Demjanjuk

Editorial

On May 13th news headlines around the world announced the conviction of John Demjanjuk for having been a guard at the infamous Sobibor concentration camp. Demjanjuk it would seem was found guilty as an accessory to the murder of some 28,060 people. Oddly, however, if one reads beyond the headlines, it is revealed that there was no evidence that Demjanjuk committed any specific crime. The conviction was based on the legally declared “fact” that if he was at the camp, he had to have been a participant in the killing. But if convicting a man without evidence isn’t strange enough, Judge Ralph Alt ordered Demjanjuk sentenced to 5 years in prison but released him from custody, noting that he had already served two years during the trial and had served 8 years in Israel on related charges which were later overturned. Was this verdict truly about carrying out justice for crimes committed 65 years prior or was it simply the wisdom of a judge who could placate all sides by setting a 91-year-old man free but still pronouncing him guilty?

To better understand the recent events, we need to turn back the pages of this story nearly 70 years. During World War Two, Demjanjuk fought in the Red Army against the Nazis but by the summer of 1942 had become a prisoner of war. During his captivity, Demjanjuk was recruited into a Wehrmacht auxiliary unit along with some 50,000 other Russians and Ukrainians. Following the war, he immigrated to the United States. He became an American citizen in 1958 and landed a job at the Ford automobile manufacturing plant in Cleveland, Ohio.

In the years that followed Demjanjuk made the fateful decision to send his wife Vera back to the Ukraine to tell his mother that he had survived the war and was living in the United States. Word of the visit spread and soon the KGB investigated. Payments that the Soviets were making to his mother for her presumed dead war hero son were abruptly stopped.

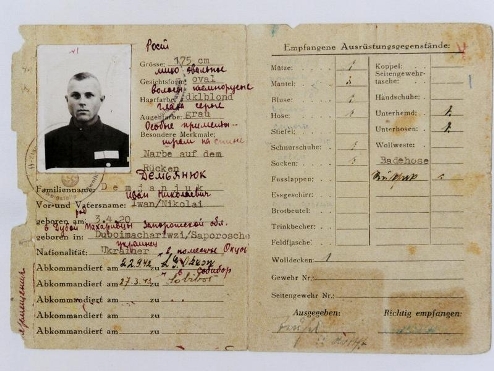

In 1976, troubles for Demjanjuk magnified when the Ukrainian Daily News, a New York based Communist newspaper, published an ID card from the Trawniki camp in Poland. This camp was said to be a training center for ex-POWs who had volunteered to serve in the Nazi SS. The article identified the man in the photo as one Ivan Demjanjuk and announced that he was living in the United States.

Much has been written about this card including the charge that it is a forgery. It has no date of issue, the SS symbol was entered by hand, and it has been asserted that the photo of Demjanjuk was added after the fact. Photo: US Department of Justice.

In 1981 John Demjanjuk went through a trial to rescind his American citizenship. This resulted in his extradition to Israel in 1986 where he was to stand trial for being “Ivan the Terrible” who it was said operated the diesel gas chambers of Treblinka. Some sources charged Demjanjuk with being responsible for a half-million murders. Soon the numbers would grow even greater with some citing his personal responsibility for upwards of 900,000 murders. The big question was not the plausibility of the alleged crime itself, but rather, was John in fact the Ivan that the prosecution claimed he was?

Evidence in the case was largely limited to the Trawniki ID card and the fading memories of a few purported eyewitnesses. The case seemed to be unraveling when it was revealed that star prosecution eyewitness Eliahu Rosenberg had made a statement in 1947 that he had killed Ivan of Treblinka in August of 1943.

The ID card also came into question and even popular columnist Pat Buchanan labeled it a forgery. The German newspaper Der Spiegel noted that a Bavarian handwriting expert discovered that official stamps on the card had been faked, the German used was full of mistakes, and punctuation was missing or had been added by hand. Moreover, the number on the ID card, 1393, was issued before Demjanjuk was even captured. During the recent trial in Germany, it was revealed that a previously classified report by the FBI argued that the ID card was “quite likely fabricated” by the Soviets. Demjanjuk defenders had argued for years that the Justice department was withholding evidence. Apparently, they were correct.

Despite the threadbare evidence, in 1988 Demjanjuk was found guilty in his first trial, in Israel, and sentenced to death by hanging for his crimes. His attorneys appealed and after several years of solitary confinement, his case went to the Israeli Supreme Court. While most media outlets had already served as Demanjuk’s judge, jury, and hangman, the Israeli Supreme Court carefully weighed the evidence. Shevah Weiss, a member of the Israeli Knesset and Holocaust survivor declared “The judges will decide. I’m sure they will not send someone to hang if he is innocent.” Indeed, in a surprise conclusion, the Israelis found the evidence for his conviction insufficient and released him in July of 1993.

While many considered the matter closed, various Jewish organizations continued to hound Demjanjuk. The thought was apparently that even if Demjanjuk was not the fiend of Treblinka, he must have been guilty of some other Holocaust related crime. In 1999 the US Justice Department filed a new civil complaint against Demjanjuk.

On April 30, 2004, a three-judge panel ruled that Demjanjuk could be again stripped of his citizenship because the Justice Department had presented “clear, unequivocal and convincing evidence” of his service in Nazi concentration camps. In December 2005, Demjanjuk was ordered to be deported. In an attempt to avoid deportation, Demjanjuk sought protection under the United Nations Convention against Torture, claiming that he would be prosecuted and tortured if he were deported to Ukraine. Chief U.S. Immigration Judge Michael Creppy ruled that there was no evidence to substantiate Demjanjuk’s claim, and so the hounding would continue.

After several denials of his appeals right up to the US Supreme Court, Demjanjuk was deported. On June 19, 2008, Germany announced it would seek the extradition of Demjanjuk to Germany. That is where he was finally sent and stood trial.

While the trial of Demjanjuk in Germany indicated to some, including Efraim Zuroff, chief “Nazi hunter” of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, that there is hope “that this verdict will pave the way for additional prosecutions in Germany,” it should indicate to objective observers that the time for such prosecutions is over. Alleged perpetrators are in their 90s and in expectedly poor health. Eyewitnesses have faulty memories of all such events, even when they occurred less than the 65-plus years that have elapsed. Evidence is lacking. In fact the alleged crimes themselves have to generally be taken as a matter of faith by all sides. Attorneys and judges who refuse to do this face the threat of being tried and imprisoned for the crime of ‘Holocaust denial.’

While a statute of limitations should have been enacted years ago, time itself has set a limitation on the continuation of such trials. Trials that would follow Demjanjuk’s would be equally lacking in evidence. Today such trials and those who encourage them appear to be acting solely out of sheer vengefulness. Old wounds will never be healed as long as such hatred and vengeance is allowed to go on. The time is now to cease the prosecution of the events of a time that is so long past. The absurdity of such trials is highlighted by considering what would have followed if a newly elected Franklin Roosevelt were to seek to put Confederate soldiers on trial. Can anyone imagine 25 years from now some new Asiatic regime arresting, deporting and trying Americans for the murder of civilians during the Vietnam War?

Rather than hoping for additional prosecutions, we should hope that this case marks their end. It is clear that after decades of court cases no evidence fit to support a conviction has been adduced that John Demjanjuk perpetrated any crimes during the period now known as the Holocaust. It is clear however that many misguided prosecutors and activists destroyed the life of this peaceable autoworker, making him the latest and if we are lucky the last victim of the Holocaust.

In this issue of Inconvenient History, we feature an unprecedented three reviews of a single new volume. After more than a decade Samuel Crowell’s magnum opus, The Gas Chamber of Sherlock Holmes has finally come into print. The significance of this work is so great that we have decided to run reviews by historian Michael K. Smith, myself, and newcomer Ezra MacVie. We are also running two lengthy revisionist studies. First, Thomas Kues has provided the conclusion to the article begun last issue on the story of the little known Maly Trostenets “extermination camp.” Paul Grubach has also examined the recent work of Deborah Lipstadt regarding the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Grubach reveals some shocking double standards and even what he considers a contribution to historical revisionism by this well-known anti-revisionist. We also welcome back Martin Gunnells who reviews the recently published 25th anniversary edition of Michael Hoffman’s story of Ernst Zündel’s false news trials, The Great Holocaust Trial. Rounding out this issue is assistant editor Jett Rucker who considers the events of the recent Richard Goldstone affair, something he calls instant self-revisionism.

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 3(2) (2011)

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a