Zionism’s Violent Legacy

Donald Neff is author of the recently published Fallen Pillars: U.S. Policy Towards Palestine and Israel Since 1945 (Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1995), as well as of the 1988 trilogy, Warriors at Suez: Eisenhower Takes America Into the Middle East in 1956, Warriors for Jerusalem: The Six Days that Changed the Middle East, and Warriors Against Israel: America Comes to the Rescue. This article is reprinted from the January 1996 issue of The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs (P.O. Box 53062, Washington, DC 20009).

It was 48 years ago, on January 4, 1948, when Jewish terrorists drove a truck loaded with explosives into the center of the all Arab city of Jaffa and detonated it, killing 26 and wounding around 100 Palestinian men, women and children.[1] The attack was the work of the Irgun Zvai Leumi – the “National Military Organization,” also known by the Hebrew letters Etzel – the largest Jewish terrorist group in Palestine. The Irgun was headed by Revisionist Zionist Menachem Begin and had been killing and maiming Arabs, Britons and even Jews for the previous ten years in its efforts to establish a Jewish state.

This terror campaign meant that at the core of Revisionist Zionism there existed a philosophical embrace of violence. It was this legacy of violence that contributed to the assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on November 4, 1995.

The Irgun was not the only Jewish terrorist group but it was the most active in causing indiscriminate terror in pre-Israel Palestine. Up to the time of the Jaffa attack, its most spectacular feat had been the July 22, 1946, blowing up of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, with the killing of 91 people – 41 Arabs, 28 Britons and 17 Jews.[2]

The other major Jewish terrorist group operating in Palestine in the 1940s was the Lohamei Herut Israel – “Fighters for the Freedom of Israel,” Lehi in the Hebrew acronym – also known as the Stern Gang after its fanatical founder Avraham Stern. Two of its more spectacular outrages included the assassination of British Colonial Secretary Lord Moyne in Cairo on November 6, 1944, and the assassination of Count Folke Bernadotte of Sweden in Jerusalem on September 17, 1948.[3]

Both groups collaborated in the massacre at Deir Yassin, in which some 254 Palestinian men, women and children were slain on April 9, 1948. Palestinian survivors were driven like ancient slaves through the streets of Jerusalem by the celebrating terrorists.[4]

Yitzhak Shamir was one of the three leaders of Lehi who made the decision to assassinate Moyne and Bernadotte. Both he and Begin later became prime ministers and ruled Israel for a total of 13 years between 1977 and 1992. They were both leaders of Revisionist Zionism, that messianic group of ultranationalists founded by Vladimir Zeev Jabotinsky in the 1920s. He prophesied that it would take an “iron wall of Jewish bayonets” to gain a homeland among the Arabs in Palestine.[5] His followers took his slogan literally.

Begin and the Revisionists were heartily hated by the mainline Zionists led by David Ben-Gurion. He routinely referred to Begin as a Nazi and compared him to Hitler. In a famous letter to The New York Times in 1948, Albert Einstein called the Irgun “a terrorist, rightwing, chauvinist organization” that stood for “ultranationalism, religious mysticism and racial superiority.”[6] He opposed Begin's visit to the United States in 1949 because Begin and his movement amounted to “a Fascist party for whom terrorism (against Jews, Arabs, and British alike), and misrepresentation are means, and a 'leader state' is the goal,” adding:

The IZL [Irgun] and Stern groups inaugurated a reign of terror in the Palestine Jewish community. Teachers were beaten up for speaking against them, adults were shot for not letting their children join them. By gangster methods, beatings, window smashing, and widespread robberies, the terrorists intimidated the population and exacted a heavy tribute.

Ben-Gurion considered the Revisionists so threatening that shortly after he proclaimed establishment of Israel on May 14, 1948, he demanded that the Jewish terrorist organizations disband. In defiance, Begin sought to import a huge shipment of weapons aboard a ship named Altalena, Jabotinsky's nom de plume.[7]

The ship was a war surplus US tank landing craft and had been donated to the Irgun by Hillel Kook's Hebrew Committee for National Liberation, an American organization made up of Jewish-American supporters of the Irgun.[8] Even in those days it was Jewish Americans who were the main source of funds for Zionism. While few of them emigrated to Israel, Jewish Americans were generous in financing the Zionist enterprise. As in Israel, they were split between mainstream Zionism and Revisionism. One of the best known Revisionists was Ben Hecht, the American newsman and playwright. After one of the Irgun's terrorist acts, he wrote:[9]

The Jews of America are for you. You are their champions … Every time you blow up a British arsenal, or wreck a British jail, or send a British railroad train sky high, or rob a British bank, or let go with your guns and bombs at British betrayers and invaders of your homeland, the Jews of America make a little holiday in their hearts.

The Altalena was loaded with $5 million worth of arms, including 5,000 British Lee Enfield rifles, more than three million rounds of ammunition, 250 Bren guns, 250 Sten guns, 150 German Spandau machine guns, 50 mortars and 5,000 shells as well as 940 Jewish volunteers. Ben-Gurion reacted with fury, ordering the ship sunk in Tel Aviv harbor. Shell fire by the new nation's armed forces set the Altalena afire, killing 14 Jews and wounding 69. Two regular army men were killed and six wounded during the fighting.[10] Begin had been aboard but escaped injury. Later that night he railed against Ben-Gurion as “a crazy dictator” and the cabinet as “a government of criminal tyrants, traitors and fratricides.”[11]

Ben-Gurion's deputy commander in the Altalena affair was Yitzhak Rabin, the same man who as prime minister was assassinated by one of the spiritual heirs of Menachem Begin's Irgun terrorist group. All his life, and especially in his last years, Rabin had opposed Jewish-Americans and their radical allies in Israel who continued to embrace the philosophy of the Irgun and who fought against the peace process, thereby earning their enduring hatred.

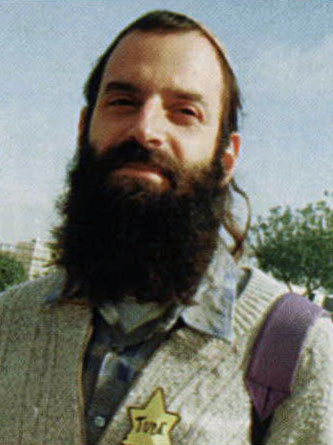

Baruch Goldstein wore a yellow Star of David with the German word for “Jew” to show his ardent concern for the “lessons of the Holocaust” and its meaning for all Jews. Today many hardline Zionists revere this mass murderer of Palestinians as a Jewish hero and martyr.

Thus at the heart of the Jewish state there has been a long and violent struggle between mainline Zionists and Revisionists that continues today. Despite cries after Rabin's assassination that it was unknown for Jew to kill Jew, intramural hatred and occasional violence have marked relations between Zionism's competing groups.

The core of that conflict, one that continues to divide Israel and its American supporters as well, lies in the different philosophies of David Ben-Gurion and Vladimir Jabotinsky. Both were from Eastern Europe, born in the 1880s, and both sought an exclusivist Jewish state. But while Ben-Gurion was pragmatic and secular, Jabotinsky was impatient and messianic, a leader who glorified in the heroic trappings of fascism. Ben-Gurion was usually willing to take less now to get more later, and thus he was content to accept partition of Palestine as a necessary stepping stone toward a larger Jewish state. Jabotinsky, on the other hand, impatiently preached the right of Jews not only to all of Palestine but to “both sides of the Jordan,” meaning the combined area of Jordan and Palestine, or as he called it, Eretz Yisrael, the ancient land of Israel.[12]

Ben-Gurion was a gruff realist who carefully calculated his moves with a wary eye toward the interests of the great European powers and the United States. Time magazine, in a profile of Ben-Gurion in August 1948, described him as “premier and defense minister, labor leader and philosopher, hardheaded, unsociable and abrupt politician, a prophet who carries a gun.[13] Wrote his biographer, Michael Bar-Zohar: “Obstinacy and total dedication to a single objective were the most characteristic traits of David Ben-Gurion.”[14]

Jabotinsky, by contrast, was flamboyant and a devoted admirer of Italy's fascist leader Benito Mussolini. His disciple, Menachem Begin, described him as “a speaker, a writer, a philosopher, a statesman, a soldier, a linguist … But to those of us who were his pupils, he was not only their teacher, but also the bearer of their hope.” Begin's biographer, Eric Silver, added: “There was a darker side to [Jabotinsky's] philosophy: blood, fire and steel, the supremacy of the leader, discipline and ceremony, the manipulation of the masses, racial exclusivity as the heart of the nation.[15] One of Jabotinsky's slogans was: “We shall create, with sweat and blood, a race of men, strong, brave and cruel.”[16]

Jabotinsky died in 1940, and it was Menachem Begin who refined his wild nationalism into practical political action. Begin concluded: “The world does not pity the slaughtered. It only respects those who fight.” He turned Descartes' famous dictum around, saying: “We fight, therefore we exist.”[17] Central to Begin's outlook was the concept of the “fighting Jew.” As he wrote:[18]

Out of blood and fire and tears and ashes, a new specimen of human being was born, a specimen completely unknown to the world for over 1,800 years, the “FIGHTING JEW.” It is axiomatic that those who fight have to hate …. We had to hate first and foremost, the horrifying, age-old, inexcusable utter defenselessness of our Jewish people, wandering through millennia, through a cruel world, to the majority of whose inhabitants the defenselessness of the Jews was a standing invitation to massacre them.

From these early leaders of Zionism (Ben-Gurion died in 1973 and Begin in 1992) have emerged their direct descendants in the Israeli political spectrum. Rabin and his successor, Shimon Peres, were both protégés of Ben-Gurion, and have carried on his mainstream secular Zionism. On Jabotinsky's and Begin's side, the followers have been Yitzhak Shamir, Ariel Sharon and, now, Benjamin Netanyahu, the current leader of the Likud.

Rabin's Strategy

While the two major factions of Zionism disagree on tactics, their ultimate aim of maintaining a Jewish state free of non-Jews was the same. Rabin explained his strategy shortly before his death during an interview with Rowland Evans and Robert Novak:[19]

I believe that dreams of Jews for two thousand years to return to Zion were to build a Jewish state and not a binational state. Therefore I don't want to annex the 2.2 million Palestinians who are a different entity from us – politically, religiously, nationally – against their will to become Israelis. Therefore I see peaceful coexistence between Israel as a Jewish state – not all over the land of Israel, on most of it, its capital the united Jerusalem, its security border the Jordan River – next to it a Palestinian entity, less than a state, that runs the life of the Palestinians. It is not ruled by Israel. It is ruled by the Palestinians. This is my goal not to return to the pre-Six-Day-War lines, but to create two entities. I want a separation between Israel and the Palestinians who reside in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, and they will be a different entity that rules itself.

In the Revisionist's vocabulary, the goal was the same, if more expansionist and expressed in more direct and pugnacious words. Former Defense Minister Ariel Sharon, a leading spokesman of Zionism's right wing, commented in 1993: “Our forefathers did not come here in order to build a democracy but to build a Jewish state.”[20]

The occupation of all of Palestine, including Jerusalem, in the 1967 war and the coming to power a decade later of Menachem Begin gave a profound boost to Revisionism and its radical philosophy. During this period there arose the firebrand Meir Kahane, a Brooklyn-born rabbi who openly espoused the removal of the Palestinians from all of Palestine. Under the influence of his fiery rhetoric, thousands of Orthodox Jewish Americans were encouraged to emigrate to Israel as settlers on occupied Palestinian land, adding to the radicalization of Israeli politics. After Kahane's assassination in New York in 1990 by an Arab, New York Times correspondent John Kifner reported that Kahane had been successful in the sense that many of his ideas “had crept into the mainstream” in Israel.

Dr. Ehud Sprinzak, an Israeli expert on the far right in Israel, observed: “Where [Kahane] has succeeded is in changing the thinking of many Israelis toward anti-Arab feelings and violence. He forced the more respectable parties to change. In the 1970s Kahane was in the political wilderness, but in the 1980s the center had moved toward Kahane.” Observed the Jewish Telegraph Agency: “Rabbi Kahane could die satisfied that his message has impacted deeply and widely throughout Israeli society.”[21]

By the mid-1990s, even Kahane's violent ideas seemed somewhat mild in the context of the radicalized politics of Israel. A new strain of religious extremism has been added to the Revisionist ranks. This became obvious on February 25, 1994, when Brooklyn-born Dr. Baruch Goldstein, a Kahane disciple, walked into the Ibrahim mosque, called the Cave of Machpela by Jews, in Hebron and killed 29 and wounded upwards of 150 Palestinian worshippers.[22] While Rabin and labor Zionists condemned him, Goldstein became a hero for Revisionist Zionists. A shrine was made of his grave and a group of Revisionists grew up called “Goldsteiners.” They are dedicated to the “sublime ideals of Goldstein” and urge “all true Jews to follow his footsteps.”[23]

While the Revisionists had always had an element of religious messianism, the most radical of their current heirs come from ultrareligious Orthodox Jews who are less consumed by politics than religion.[24] They believe they are God's messengers. Thus Rabin's assassin, Yigal Amir, cited the authority of God to explain the murder.

This is a sea change in the mindset – if not the violence – of the traditional Revisionists. For instance, in 1943 Yitzhak Shamir ordered the assassination of one of his closest Sternist friends, but offered an entirely different rationale that had nothing to do with God. Mainly the motive stemmed from political and tactical reasons. Shamir wrote in his memoirs, In the Final Analysis, that Stern commander Eliyahu Giladi had become “strange and wild” and had wanted to shoot at crowds of Jews and urged the assassination of David Ben-Gurion, acts that would have been highly unpopular. Wrote Shamir: “I was afraid that he had gone completely crazy. I knew that I had to take a fateful decision, and I didn't evade it.”[25] Giladi was fatally shot in the back on a beach south of Tel Aviv and his killer was never found.[26]

The new Revisionists have now expanded the right to kill claimed by the early Revisionists in the name of nationalism to include a divine right. In the end, they are less interested in foreign and domestic affairs than in justifying man's acts to God. It is a powerful and inflammatory mix of nationalism and religion that is almost certain to lead to more violence unless Israel is able to look into its own soul.

Recommended Reading

- Bar-Zohar, Michael, Ben-Gurion: A Biography, New York: Delacorte, 1978. Begin, Menachem, The Revolt, Los Angeles: Nash, 1972. Bell, J. Bowyer, '/error Out of Zion, New York: St. Martin's, 1977. Ben-Gurion, David, Israel: A Personal History, New York: Funk & Wagnalls, Inc., 1971.

- Bethell, Nicholas, The Palestine Triangle: The Struggle for the Holy Land, 1935-48, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1979.

- Brenner, Lenni, Zionism in the Age of the Dictators, Westport, Conn.: Lawrence Hill, 1983.

- Brenner, Lenni, The Iron Wall: Zionist Revisionism from Jabotinsky to Shamir, London: Zed Books, 1984.

- Halsell, Grace, Prophesy and Politics: Militant Evangelists on the Road to Nuclear War, Westport, Conn.: Lawrence Hill, 1986.

- Khalidi, Walid (ed.), Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians 1876-1948, Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1984.

- Khalidi, Walid, From Haven to Conquest: Readings in Zionism and the Palestine Problem until 1948, Washington, DC: Institute for Palestine Studies, second printing, 1987.

- Marion, Kati, A Death in Jerusalem, New York: Pantheon, 1994.

- Nakhleh, Issa, Encyclopedia of the Palestine Problem (2 vols.), New York: Intercontinental, 1991.

- Palumbo, Michael, The Palestinian Catastrophe: The 1948 Expulsion of a People from their Homeland, Boston: Faber and Faber, 1987.

- Rubinstein, Ammon, The Zionist Dream Revisited, New York: Schocken, 1984.

- Sachar, Howard M., A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time, Tel Aviv: Steimatzky's Agency, 1976.

- Silver, Eric, Begin: The Haunted Prophet, New York: Random House, 1984.

- Tillman, Seth, The United States in the Middle East: Interests and Obstacles, Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1982.

Notes

| [1] | Sam Pope Brewer, New York Times, Jan. 5, 1948, and Khalidi, Before Their Diaspora, p. 316. Also see Palumbo, The Palestinian Catastrophe, pp. 83-4. Initial reports put the death toll at 34. |

| [2] | Bethell, The Palestine Triangle, p. 263; Sachar, A History of Israel, p. 267. Details on the bombing and reaction of British officials are in Nakhleh, Encyclopedia of the Palestine Problem, pp. 269-70. |

| [3] | Bethell, Palestine Triangle, pp. 181-87, 263; Sachar, A History of Israel, p. 267; Marion, A Death in Jerusalem, p. 208. |

| [4] | Khalidi, From Haven to Conquest, pp. 761-78; Silver, Begin, pp. 88-96; Nakhleh, Encyclopedia of the Palestine Problem, pp. 271-72. |

| [5] | Silver, Begin, p. 12. |

| [6] | New York Times, Nov. 27, 1948. |

| [7] | Bar-Zohar, Ben-Gurion, p. 175. |

| [8] | Silver, Begin, p. 98. |

| [9] | Bethell, The Palestine Triangle, pp. 308-9. An interview reflecting Hecht's views appeared in The New York Times, May 28, 1947. |

| [10] | Silver, Begin, p. 108. |

| [11] | Silver, Begin, p. 108. |

| [12] | In Hebrew, Eretz Yisrael means the “Land of Israel,” a phrase invested with strong nationalist feelings. |

| [13] | Time, August 16, 1948. |

| [14] | Bar-Zohar, Ben Gurian, pp. 77, xvii. |

| [15] | Silver, Begin, p. 11. |

| [16] | Elfi Pallis, “The Likud Party: A Primer,” Journal of Palestine Studies, Winter 1992, p. 45. |

| [17] | Begin, The Revolt, pp. 36, 46. Also see Tillman, The United States in the Middle East, p. 20. |

| [18] | Begin, The Revolt, pp. xi-xii. Also see Elfi Pallis, “The Likud Party: A Primer,” Journal of Palestine Studies, Winter 1992, p. 45. |

| [19] | Evans and Novak, CNN, Oct. 1, 1995. |

| [20] | Menachem Shalev, Forward, May 21, 1339. |

| [21] | John Kifner, New York Times, Nov. 11, 1990. |

| [22] | David Hoffman, Washington Post, Feb. 28, 1994. |

| [23] | Khalid M. Amayreh, “Six Months On,” Middle East International, Sept. 9, 1994. |

| [24] | Halsell, Prophecy and Politics, p. 75, provides an excellent analysis of the extremist beliefs of Jabotinsky and his fol· lowers and their alliance with American fundamentalist Christians such as Jerry Falwell, leader of the Moral Mliority. |

| [25] | Clyde Haberman, New York Times, Jan. 15, 1994. |

| [26] | Glenn Frankel, Washington Post, Nov. 6, 1995. |

Natural Rebellion

“What country before ever existed a century and a half without a rebellion? .. The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.”

—Thomas Jefferson, January 30, 1787

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 16, no. 1 (January/February 1996), pp. 42-45; reprinted from The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, January 1996.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a