Ernst Kaltenbrunner: Framed at Nuremberg

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (1903-1946) was chief of the Reich Main Office for Security (RSHA) from January 1943 until the end of World War II. In this position, he directed the operations of the Secret State Police (Gestapo), the Criminal Police (Kripo), and the Security Service (SD). Of the German leaders who stood before the International Military Tribunal (IMT) in 1945, few inspired more revulsion and contempt than Kaltenbrunner.[1]

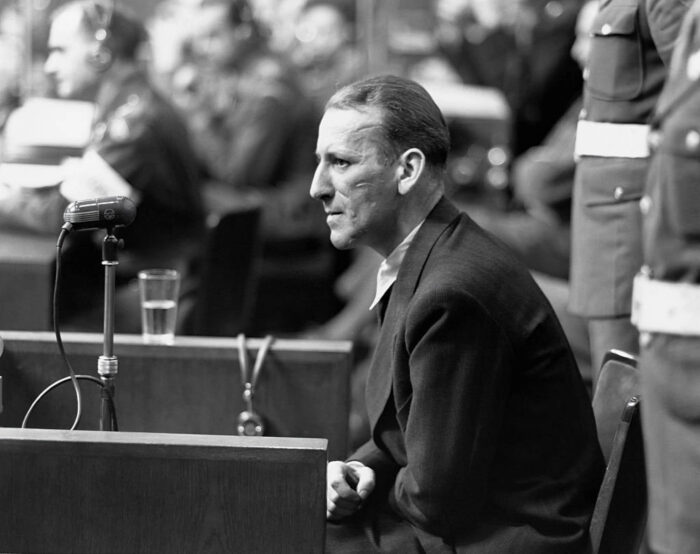

Telford Taylor, an American prosecutor at the IMT, described Kaltenbrunner as a “brutish, scar-faced hulk.” Taylor wrote that Kaltenbrunner “was the most ominous-looking man in the dock and had no friends there.” Rebecca West wrote that he “looked like a vicious horse.”[2] Hans Bernd Gisevius, a prosecution witness at the IMT, testified that Kaltenbrunner had “an even more sadistic attitude than Himmler.”[3] Author Evelyn Waugh, observing the defendants from the spectators’ gallery, noted that “only Kaltenbrunner looked an obvious criminal.”[4]

This article examines the life of Kaltenbrunner, and whether or not the accusations made against him at the IMT are true.

Early Life

Ernst Kaltenbrunner was born in Reid, the industrial capital of the western part of the state of Upper Austria. Kaltenbrunner was the son of a lawyer, and his family had achieved a degree of respect in government, in the legal profession, and even in literature. Nothing in his ancestral or family background hinted at his having inherited an abnormal personality or being a social misfit. The Kaltenbrunner family viewed themselves—and were viewed by others—as “straightforward members of the solid middle class.”[5]

Kaltenbrunner moved to the town of Raab, Austria in 1906. He spent seven happy years there, and later said that at Raab he “came to feel a love for nature and an interest in the passion and joys of a simple life.” He left his family in 1913 to attend the Realgymnasium in Linz. Kaltenbrunner’s memories of his years in Linz were not pleasant, and he felt deeply homesick for Raab.[6]

The end of World War I brought the Kaltenbrunner family back together again when Kaltenbrunner’s father closed his law practice in Raab to join a law firm in Linz. Kaltenbrunner graduated from the Realgymnasium in Linz in 1921, and matriculated that autumn to a technical university in Graz. After majoring in chemistry for two years, Kaltenbrunner transferred to the university’s law school, from which his father had graduated 25 years earlier. He completed his law degree in July 1926.[7]

Kaltenbrunner served his mandatory first year of legal training as a court apprentice at the Linz District Court. He moved to Salzburg after his legal apprenticeship to take a position in a law firm, and, in 1928, moved back to Linz to work for another law firm. On October 18, 1930, Kaltenbrunner joined the Austrian National-Socialist Party. He became a member of the SS 10 months later in August 1931. Kaltenbrunner told his relatives that, above all, he hoped for the union of Austria and Germany. This was the determining factor in his decision to join the National-Socialist Party.[8]

Austrian SS Chief

Kaltenbrunner displayed a remarkable ability to advance his career and garner influence in the Austrian National-Socialist Party. He became active as a district speaker in Upper Austria, and gave free legal aid to SS men accused of criminal activities. The Austrian government began to apply increasing pressure on the National Socialists. Austrian authorities established several detention camps in the fall of 1933, and Kaltenbrunner learned that he would be arrested in an impending roundup. He quickly married his fiancé on January 14, 1934. The next day, Kaltenbrunner was arrested and sent to a detention camp.[9]

Kaltenbrunner and several of his fellow inmates organized a hunger strike in April 1934 to protest the inadequate food rations, faulty sanitation facilities and frequent mistreatment of the prisoners in their camp. They demanded that all prisoners be released. The hunger strike continued until Kaltenbrunner and several of his companions, weak from hunger, were evacuated to a hospital and released. More significant for Kaltenbrunner’s political future was the close friendship that he established with one of his bunkmates in the camp—the agricultural engineer Anton Reinthaller.[10]

Reinthaller convinced Kaltenbrunner that, given the political situation in Austria, National Socialists needed to present a moderate front. While serving as Reinthaller’s secretary, however, Kaltenbrunner was arrested on suspicion of high treason. Kaltenbrunner was convicted of membership in the illegal SS, sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, and had his license to practice law revoked. Although many SS members who were imprisoned or lost their jobs emigrated to Germany, Kaltenbrunner stayed in Austria. He was appointed chief of SS-Abschnitt VIII (Upper and Lower Austria) by Heinrich Himmler in the fall of 1935.[11]

In order to report to his superiors in the SS, Kaltenbrunner frequently bypassed the Austrian SS leader by traveling to Germany to report directly to Himmler and other SS officers. Kaltenbrunner impressed SS leaders not only with his political acumen, but also through his reputation as an intelligence expert. Reflecting Himmler’s appreciation of Kaltenbrunner’s leadership abilities, on March 21, 1938, Himmler appointed Kaltenbrunner as chief of the Austrian SS. Kaltenbrunner was also awarded the role of state secretary for security in the Austrian government.[12]

RSHA Chief

As chief of the Austrian SS, Kaltenbrunner conducted intelligence operations and worked on routine police administration, transmission of Security Police orders from Berlin to police units in Vienna, supervision of the indoctrination of new SS recruits, and the amalgamation of the SS and police in the SS-Oberabschnitt Donau. With few personal connections in Germany other than Himmler, Kaltenbrunner appeared to have reached a professional dead end. However, when RSHA chief Reinhard Heydrich died on June 4, 1942 from wounds received in an assassination operation carried out by Czech agents, the top spot in the RSHA became vacant.[13]

Himmler took control of the RSHA for the first eight months after Heydrich’s death. By early December 1942, Himmler decided to replace himself with Kaltenbrunner. After receiving Hitler’s approval in January 1943, Himmler summoned Kaltenbrunner to Berlin and told him to take over management of the RSHA. Kaltenbrunner remained as head of the RSHA until the end of the war.[14]

Himmler clearly wanted Kaltenbrunner to utilize the power that Heydrich had held prior to Heydrich’s death. He advised Kaltenbrunner to “reestablish the contacts that Heydrich had held in his hands.” Kaltenbrunner had a mixed reaction to his new job. While Kaltenbrunner liked its promise of power, excitement and intrigue, he was nervous about suddenly being thrust into the mainstream of National-Socialist politics. Otto Skorzeny said that Kaltenbrunner “even with all the external splendor, did not feel quite at home there [in the RSHA].”[15]

The German Sixth Army surrendered to the Russians at Stalingrad only three days after Kaltenbrunner became head of the RSHA. This disaster was followed by the surrender of the German Army in North Africa on May 7, 1943, and the Allied landings in Sicily and Italy in July and September 1943.[16] These losses foretold Germany’s future defeat, and Kaltenbrunner’s later death by hanging at Nuremberg.

Wartime Activities

Similar to Heydrich, Kaltenbrunner’s primary interests were in military intelligence and counter-espionage. When he became head of the RSHA on January 30, 1943, he had the firm intention of acquiring control of the Abwehr intelligence organization headed by Adm. Wilhelm Canaris. Kaltenbrunner had a hostile personal talk with Canaris in Munich three weeks later. Canaris won this confrontation, and Himmler warned Kaltenbrunner that he would not tolerate any interference in the Abwehr.[17]

Kaltenbrunner achieved his ambition of acquiring control of the Abwehr when it became a branch of the RSHA in February 1944. He followed Canaris’s policy of seeking contacts with the West. Sometimes Kaltenbrunner worked with Walter Schellenberg; other times he employed Wilhelm Höttl, who had contacts with American OSS agent Allen Dulles. Kaltenbrunner believed that the SS, as disposers of an army within an army, held the best cards for bargaining with the Western Allies.[18] Kaltenbrunner competed with several SS leaders to negotiate peace with Western representatives.[19]

Germany’s labor supply dwindled rapidly as the war wore on. Thousands of Poles and Soviets were put to work in factories and on farms throughout Germany, Austria, Bohemia, Moravia and the Government General. Kaltenbrunner issued a circular on June 30, 1943, establishing regulations for punishing crimes committed by Poles and Russians in Germany. The Gestapo and the Kripo were to handle all criminal proceedings. Kaltenbrunner’s circular said the only exception were those cases where “for reasons of general political morale a court verdict seems desirable and where it is arranged beforehand that the court would impose the death sentence.”[20]

Kaltenbrunner has also been criticized for his policies regarding sexual relations between Germans and foreign laborers. He issued a decree in February 1944 that defined sexual intercourse between Germans and Poles, Lithuanians, Russians and Serbs as a crime subject to prosecution by the Security Police. If the male was non-German, he would be subject to immediate arrest, while a German male could be prosecuted only if he had utilized his official position to force sexual relations. Non-German females could be expected to be interned in a concentration camp.[21]

On May 16, 1945, U.S. Army forces captured Kaltenbrunner in the Austrian Alps. Kaltenbrunner had left his family in Austria and hidden with several companions in a hunting lodge high in the mountains southeast of Salzburg. A local hunter, however, betrayed him to the U.S. Army. When U.S. Army agents brought Kaltenbrunner face to face with his mistress, who’d born him twins six weeks earlier, she “confirmed Kaltenbrunner’s identity by impulsively embracing him.”[22]

Nuremberg Trial

The IMT indicted six former National-Socialist organizations as criminal, including the SS, its intelligence arm, the Security Service, and the Gestapo. Allied prosecutors chose Kaltenbrunner to stand trial because, in the fall of 1945, he was the highest-ranking SS officer still alive and in custody. Kaltenbrunner’s responsibilities linked him to the Gestapo, the Einsatzgruppen in Russia, and the German concentration camps.[23]

The Allies transported Kaltenbrunner to Nuremberg in September 1945 after 10 weeks of imprisonment and extensive questioning in London. The IMT served Kaltenbrunner an indictment on October 19, charging him with perpetration of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and participation in a conspiracy to commit such crimes. American psychologist Dr. Gustave Gilbert, as he did with other defendants, asked Kaltenbrunner to sign the indictment and write his view of it. Kaltenbrunner complied, writing:[24]

“I do not feel guilty of any war crimes, I have only done my duty as an intelligence organ, and I refuse to serve as an ersatz [substitute or stand-in] for Himmler.”

Dr. Gilbert said to Kaltenbrunner that most people will doubt that, as nominal chief of the RSHA, Kaltenbrunner had nothing to do with the concentration camps and knew nothing about the alleged German mass murder program. Kaltenbrunner responded:[25]

“But that is because of newspaper propaganda. I told you when I saw the newspaper headline ‘GAS CHAMBER EXPERT CAPTURED’ and an American lieutenant explained it to me, I was pale with amazement. How can they say such things about me? I told you I was only in charge of the Intelligence Service from 1943 on. The British even admitted that they tried to assassinate me because of that—not because of having anything to do with atrocities, you can be sure of that.”

When the IMT held its first session on November 20, 1945, Kaltenbrunner stayed in his cell, too ill to attend. Kaltenbrunner had been rushed to the hospital two days before with a subarachnoid hemorrhage. During the next few months, he attended court only a few hours at a time. Hermann Göring said about Kaltenbrunner’s fitness to stand trial, “If he’s fit, then I’m an Atlas.”[26]

Kaltenbrunner’s defense at the IMT rested on two main points. First, he was head of the RSHA, which was charged with security, and not the head of the WVHA, which administered the concentration camps. His only involvement with the internal operation of the camps was his order of March 1945, which gave permission for the Red Cross to establish itself in the camps. Second, Kaltenbrunner said it was Heydrich who had organized the details of the Jewish policy, whatever that policy was. Thus, according to Kaltenbrunner, there was no respect in which he could be held responsible for the extermination of the Jews.[27]

Kaltenbrunner’s defense strategy was his only realistic chance for acquittal on the extermination charge. If he had testified that no extermination program had existed, any leniency shown by the court in the judgment would have been tantamount to the court’s conceding the possible untruth of the extermination claim. This was a political impossibility. By claiming that Kaltenbrunner had no responsibility for the extermination program, and even opposed it, the defense was making it politically possible for the court to be lenient in its sentencing of Kaltenbrunner.[28]

The IMT judges decided Kaltenbrunner was guilty of Count Three (war crimes) and Count Four (crimes against humanity). He was the third defendant to be hanged. Much steadier than had been expected, Kaltenbrunner said:[29]

“I served the German people and my fatherland with a willing heart. I did my duty according to its laws. I am sorry that in her trying hour she was not led only by soldiers. I regret that crimes were committed in which I had no part. Good luck, Germany.”

Conclusion

Ernst Kaltenbrunner should not have been executed at Nuremberg. During Kaltenbrunner’s cross examination, he was indignantly asked how he had the nerve to pretend he was telling the truth, while 20 to 30 witnesses were lying. These witnesses did not appear in court; they were merely names on pieces of paper.[30]

One of these witnesses was Franz Ziereis, the commandant of the Mauthausen concentration camp. Ziereis confessed to gassing 65,000 people, and accused Kaltenbrunner of ordering everyone in the entire Mauthausen camp to be killed upon the approach of the Americans. Ziereis had been dead for over 10 months when he made this so-called confession. Ziereis’s “confession” was remembered by an inmate named Hans Marsalek, who never appeared in court, but whose signature appeared on the document.[31]

Eyewitness statements from Ziereis and other witnesses claiming prussic acid was streamed through shower heads into homicidal gas chambers at Mauthausen are not credible. Germar Rudolf writes:[32]

“Zyklon B consists of the active ingredient, hydrogen cyanide, adsorbed on a solid carrier material (gypsum) and only released gradually. Since it was neither a liquid nor a gas under pressure, the hydrogen cyanide from this product could never have traveled through narrow water pipes and shower heads. Possible showers, or fake shower heads, could therefore only have been used to deceive the victims; they could never have been used for the introduction of this poison gas. There is general unanimity as to this point, no matter what else might be in dispute.”

Historian Tomaz Jardim incorrectly writes that “Mauthausen had the infamous distinction of containing the last gas chamber to function during the Second World War.”[33] In reality, Mauthausen never had a homicidal gas chamber, and even many Jewish historians have acknowledged this fact.[34]

IMT defendant Hans Fritzsche wrote:[35]

“After the excitement of the cross-examinations had died down and we were awaiting the verdict, I tried to get to know Kaltenbrunner better. I soon came to the conclusion that he knew far more than I about the technique of extracting confessions during a process of questioning, and I noticed that he himself ascribed the success of the principal charges against him to the coercion or cajoling of the witnesses concerned. […]

Many a novelist, I feel, could conjure up a profile of Kaltenbrunner. But I doubt if any would depict the whole truth, for the last head of the RSHA knew far more than he ever told.”

Notes

| [1] | Black, Peter R., Ernst Kaltenbrunner: Ideological Soldier of the Third Reich, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984, p. 3. |

| [2] | Taylor, Telford, The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials: A Personal Memoir, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992, pp. 228, 360. |

| [3] | Ibid., p. 375. |

| [4] | Black, Peter R., Ernst Kaltenbrunner: Ideological Soldier of the Third Reich, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984, p. 3. |

| [5] | Ibid., pp. 27-29. |

| [6] | Ibid., pp. 28, 31-33. |

| [7] | Ibid., pp. 33-34. |

| [8] | Ibid., pp. 52-55, 61, 63. |

| [9] | Ibid., pp. 69, 71, 74. |

| [10] | Ibid., pp. 74-75. |

| [11] | Ibid., pp. 78-79. |

| [12] | Ibid., pp. 82, 94, 102, 104. |

| [13] | Ibid., pp. 116, 127. |

| [14] | Ibid., p. 128. |

| [15] | Ibid., pp. 132-133. |

| [16] | Ibid., pp. 133, 218. |

| [17] | Reitlinger, Gerald, The SS: Alibi of a Nation, 1922-1945, Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1981, p. 237. |

| [18] | Ibid., pp. 237-238. |

| [19] | Black, Peter R., Ernst Kaltenbrunner: Ideological Soldier of the Third Reich, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984, p. 255. |

| [20] | Ibid., pp. 140-141. |

| [21] | Ibid., p. 141. |

| [22] | McKale, Donald M., Nazis after Hitler: How Perpetrators of the Holocaust Cheated Justice and Truth, Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2012, p. 136. |

| [23] | Ibid., pp. 135-136. |

| [24] | Ibid., p. 136. |

| [25] | Gilbert, G. M., Nuremberg Diary, New York: Farrar, Straus and Company, 1947, p. 255. |

| [26] | Irving, David, Nuremberg: The Last Battle, London: Focal Point Publications, 1996, pp. 163-164. |

| [27] | Butz, Arthur R., The Hoax of the Twentieth Century: The Case against the Presumed Extermination of European Jewry, Newport Beach, Cal.: Institute for Historical Review, 1993, pp. 180-181. |

| [28] | Ibid., pp. 181-182. |

| [29] | Taylor, Telford, The Anatomy of the Nuremberg Trials: A Personal Memoir, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992, pp. 589, 610. |

| [30] | Porter, Carlos, Not Guilty at Nuremberg: The German Defense Case, p. 15. |

| [31] | Ibid. |

| [32] | Rudolf, Germar, The Rudolf Report: Export Report on Chemical and Technical Aspects of the ‘Gas Chambers’ of Auschwitz, 2nd edition, Washington, D.C.: The Barnes Review, 2011, p. 220. |

| [33] | Jardim, Tomaz, The Mauthausen Trial, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012, p. 3. |

| [34] | For example, see Bauer, Yehuda, A History of the Holocaust, New York: Franklin Watts, 1982, p. 209. |

| [35] | Fritzsche, Hans, The Sword in the Scales, London: Allan Wingate, 1953, pp. 186-187. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2022, Vol. 14, No. 2. A version of this article was originally published in the January/February 2022 issue of The Barnes Review.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a