Memoir by Veteran ADL Official Provides Revelations

Book Review

Square One, by Arnold Forster. New York: Donald I. Fine, 1988. Hardcover. 423 pages. Photographs. Index. ISBN: 1-55611-104-5.

John Cobden is the pen name of an American writer whose essays on political issues have appeared in nationally-circulated magazines and major daily newspapers, including the Hartford Courant and the Orange County Register. His writings on aspects of the Holocaust issue have appeared in The Journal of Historical Review and, in translation, in the French journal Revue d'Histoire Revisionniste.

By any objective standard, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) of B’nai B’rith is one of the most influential organizations in America today. Its ability to cajole, intimidate and pressure politicians, newspapers and broadcasters is legendary. In recent years, it has devoted considerable effort to countering the growing impact of Holocaust Revisionism.

During the last several months, the ADL’s nationwide “intelligence gathering” operations have come under critical scrutiny. Although the Gerard/Bullock “ADL spy scandal” is still unfolding, police officials have already charged the ADL with criminal conduct, and some of the ADL’s many victims have filed a class action suit against the powerful Zionist organization.

For more than forty years Arnold Forster, the author of this memoir, served as General Counsel and Associate National Director of this misnamed organi-zation. I say misnamed because any unbiased reader of this boastful work cannot help but conclude that defamation has been a hallmark of Forster’s career.

He has written a dozen books, most of them polemical attacks against alleged anti-Semites, particularly in the conservative movement. In his work for the ADL, Forster (who changed his name from Fastenberg) has been quick to pin the anti-Semite label on just about anyone suspected of harboring less than total support for Israel and the Jewish people. While his accusations have doubtless often been correct, in many cases his charge of anti-Semitism – just about the most harmful thing any public figure can be called – has had little or no basis in reality, except in the tortured logic of a professional anti-anti-Semite.

Praise from Wiesel

In his fulsome foreword to Square One, Elie Wiesel makes clear that he, along with Forster, regards any critic of Israel as an enemy of the Jews and, by extension, of humanity. (pp. 17, 18). In praising Forster, Wiesel writes:

What is the anti-Zionist campaign, the anti-Israeli propaganda, if not the same archaic hatred [against Jews] in modern dress?… Here is a fearless man who refuses all compromise when it comes to defending the Jewish people, and through it, all of humanity… He loves Israel, as I do, with all his heart.

This arrogant Jews=humanity equation doesn’t work in reverse, though. Wiesel would never praise anyone as “a fearless man who refuses all compromise when it comes to defending the Palestinian (or German, or Spanish or …) people, and through it, all of humanity.”

In an effort to justify a belief in Jewish moral superiority, Forster writes: “No other religion, it was pointed out, so celebrated the principle of freedom.” (p. 138) Whatever the merits of this view, if the actions of Arnold Forster and the ADL – as recorded in this book – are any indication, he has fallen woefully short of this proclaimed ideal.

Suppressing Free Speech

Forster tells us that the ADL “was chartered to defend against defamation,” and that it has “a reputation for reliability and accuracy.” (p. 151) He suggests that his accusations are always based on solid evidence. As he acknowledges here, though, Forster has spent much of life working to suppress the free speech rights of those whose views he does not like. This book establishes that the only evidence Forster needs to accuse someone of anti-Semitism is his own say-so.

Mystical Insight

In his foreword, Wiesel warns us that we will break into tears when we read Forster’s account of how he responded to an attack against his son, Stubs. Forster’s account (pp. 179, 180) may not bring tears, but it does provide an enlightening insight into the workings of the mind of a professional anti-anti-Semite. (For no apparent reason, we are parenthetically told that Stubs is blond, and that he now also has a son who is blond.)

Arnold Forster describes an evening in December 1965 when he learned by telephone that Stubs had been found beaten and unconscious on a roadside, apparently the victim of an attack. The narration continues as he describes the drive to the hospital with his wife and daughter, Jayne:

Leaning forward, straining to see the road, I remember I kept muttering, “the sons of bitches, the sons of bitches.”

After a long silence, Jayne spoke up. “Dad, why’d they beat up Stubs? Did he do something wrong?”

“They went after him Jayne, because he’s my son, your brother.”

“Why, what’d you do?”

“I defend the Jews.”

Thus, without any evidence whatsoever, Arnold Forster claimed to know that his son was attacked because he “defend[s] the Jews.” (To this day, no one has ever been charged in the incident.) Forster’s instant accusation of anti-Semitic motivation was a reflex assumption based, apparently, on what might be called a mystical revelation.

Violence Against Nazis

The casual reader might easily assume that Forster is opposed to violence as a means of silencing political opponents. That would be an error. Early on, Forster recounts an incident in which he and a group of friends encountered some youths who, he says, were marching through the street chanting “Up with Hitler, down with the Jew.” (p. 40) Forster tells how he and his buddies responded:

When they got to where we were standing, without a word passing among the five of us we stepped off the sidewalk into their path. Fists, as they say, flew. Five young attorneys, we should probably have known better. But also healthy and outraged, ours was a spontaneous combustion. The sudden brawl turned out to be a short-lived free-for-all.

While Forster is outraged because of violence allegedly directed at his son because of his views, he is himself ready to engage in violence against those whose politics he finds offensive. As this memoir makes abundantly clear, this is hardly the only example of Forsters’ abiding hypocrisy.

He tells us (p. 43) of his “anti-Nazi street-corner speeches.” These

presentations were freewheeling, not limited strictly to anti-Semitism; they ranged across the spectrum of what we thought was the broader problem. Any danger signal was worth mentioning, and danger signs were all around. For example, the Smith Act was adopted, making it a crime to advocate or teach the need to overthrow the government, or belong to a group dedicated to such a purpose. Entirely opposed to Communism, we nevertheless had deep misgivings about the outlawing of mere advocacy. Democracy, we argued, was being eroded by methods intended to protect it.

As touching as these words might be, they are not sincere. In Forster’s view, the First Amendment protects Communists but not real or imagined Nazis, anti-Semites or other “hatemongers.” While proudly defending, in the name of “democracy,” his own right, and that of Communists, to speak freely, he doesn’t refrain from dubious legal actions and even fist-fights to squelch the free speech of those he hates.

Forster tells how he made use of the police in fighting his ideological battles. Any “Nazi” who dared speak in public was put under surveillance by Forster and his friends. In each case, at least two of them “were assigned to attend meetings along with one of our attorneys. If a speech or the situation warranted it, one was to make a complaint to a nearby policeman and request the immediate arrest of the speaker. The other layman would be a witness.” (p. 42) The only crime committed by these individuals was to make a speech of which Forster did not approve. “We got convictions …” he brags.

Shylockian Legal Pretexts

To this his one-sided interpretation of the Constitutional right of freedom of speech, Forster provides an unusual legal theory. After describing a stern lecture by a judge who chastised him for his opportunistic construction of the First Amendment (p. 45), Forster relates:

The magistrate may have been well grounded in his interpretation of the First Amendment guarantee of free speech and assembly. But my research has persuaded me that the Constitution does not protect “fighting words” that incite immediate violence, even if the violence is immediately prevented by the attending police.

“Fighting words,” in Forster’s arrogant view, are only words that provoke violence by him and his ideological friends. As Forster interprets the Constitution, an individual’s First Amendment rights depend on the subjective, emotional reactions of his opponents. (As we have repeatedly seen, professional anti-anti-Semites need little to provoke them to violence. For example, the mere presence of Ernst Zündel as walked into a Toronto courtroom in 1985 to stand trial was enough to rouse a mob to fury enough to begin beating him.)

Forster’s view of the First Amendment is dangerous because much language that is quite acceptable to most people can incite violence in a few. If his view were ever to became the prevailing legal norm, there would be no First Amendment left.

Forster tells of another special First Amendment legal theory, this one dealing with broadcasters. Some decades ago, a member of the Ku Klux Klan named Lycergus Spinks ran for governor of Mississippi. A campaign speech by Spinks delivered over a Mississippi radio station so enraged Forster and his ADL colleagues (p. 84) that they responded with open legal action along with press releases and refusal to sit still in the face of a klansman advocating his own election by defaming Jews. But the legal action was not directed at Spinks. I proceeded against the radio station that was involved, interpreting existing laws to mean that because broadcasters were licensed by federal authorities they were not in the same category as newspapers, which were entitled to First Amendment protection.

In Forster’s view, government licensing removes First Amendment rights for radio (and presumably television) stations. So pleased was he with his unique interpretation of the Constitution (p. 84) that he brought similar suits against other radio stations:

Additional complaints were filed with the FCC about other stations that permitted the Spinks style of inflammatory comment. We won a number of cases, lost more. In some situations station owners backed away from giving their microphones to professional bigots after we complained to the FCC. At other times they fought us even while learning that allowing hatemongers the use of their facilities was to risk their licenses.

What Forster calls a victory here was, in reality, a dangerous defeat for the First Amendment rights of all Americans.

Unfortunately, such shenanigans are not just unsavory episodes from the distant past. Just a few years ago the Anti-Defamation League, with Forster’s active participation, successfully intimidated numerous radio stations into canceling their broadcasts of allegedly anti-Israel commentaries of Liberty Lobby – the populist organization based in Washington, DC. In addition to the tactics that had proven their worth in the Mississippi case, the ADL pressured businesses into withdrawing advertising from the offending stations.

Other Measures

One such station, WVOX of New Rochelle, New York, pointed out that while Liberty Lobby paid for its air time, Forster’s own radio program, “Dateline Israel,” was carried free of charge. Station president William O’Shaughnessy told The New York Times that he and his station took pride in presenting a diverse range of opinions. Forster responded by insisting that the Liberty Lobby broadcast “is outside the spectrum of legitimate discussion and cannot be balanced by an equal number of programs on the ‘pro’ side.” The only side of this issue that deserves First Amendment protection, Forster implicitly asserts, is the one that supports Israel. In Forster’s view, the only legitimate “debate” about US support for Israel should be over how much aid American taxpayers should be giving. (For a fascinating narration of the ADL campaign to ban Liberty Lobby from the airwaves, read Conspiracy Against Freedom. This book includes many of the actual letters and internal documents used by the ADL in this campaign.)

Forster approvingly recounts other attacks against First Amendment rights. During the war, the Roosevelt administration charged 28 right-wing and isolationist leaders with “conspiracy to promote revolution in the US armed forces.” (p. 81) After eight months the trial was suspended, and two years later the indictment was dismissed and the case closed. But Forster expresses no disapproval of this blatant attempt to suppress political opposition. To the contrary. “If the litigation did nothing else,” he writes, “it as least interrupted some of the most divisive activities this nation has ever known.” (pp. 81–82)

Another pernicious action that Forster finds entirely laudable was Franklin Roosevelt’s shutting down of Social Justice, the magazine of the popular “radio priest,” Father Charles Coughlin. (p. 82) As Forster notes:

Federal authorities revoked the paper’s second-class mailing privilege, barred it from the U.S. mails and charged it with being in violation of the 1917 Espionage Act for “aiding the enemy” by disseminating Nazi propaganda. President Roosevelt’s making clear his attitude to cabinet members undoubtedly was the reason for the Post Office Department’s action.

Anti-Anti-Communism

Further pointing up his own shameless hypocrisy, just a few years later Forster was hard at work defending Communists and other left-wingers from investigation by the US Congress. In the case of such “innocent people,” he stridently argues, a person’s political opinions must not be a factor in employment.

Forster claims (p. 170) the existence of a secret right-wing conspiracy of unnamed individuals who allegedly used a “blacklist” to keep Communists from getting jobs:

I said the blacklist, to my knowledge, was the creation of a cabal of extremist self-styled anti-communists using their cause to deny their victims the right to earn a living for having allegedly radical political views.

Forster reluctantly admits that some of those he defended did, in fact, work with Communist front groups. He concedes, for example, that John Garfield (originally Julius Garfinkel), a boyhood friend who was a popular movie actor during the 1940s, “had without question time and again, joined paths with some undoubted Communists.” (p. 151) In his defense, Forster writes that Garfield “was an extraordinarily gullible liberal or at worst, a political fool” who “unwittingly allowed his name to be used by politically sophisticated, camouflaged Communist sharpshooters.” (p. 154)

Forster devotes an entire chapter of this book to defending the “tragic” Garfield case. The ADL official has a special motive here because Garfield was a key speaker at the May 1948 ADL Annual Dinner. (p. 109)

Forster approvingly notes an attack in the ADL bulletin against anti-Communist Senator Joseph McCarthy that expressed alarm at “the disturbing tendency sweeping across our country toward blind and indiscriminate hatred for those with whom one disagreed.” (p. 160) This trend toward conformity, the ADL bulletin went on, was “stultifying” and could be “murderous.” So upset was Forster that Communists were being investigated that he wrote an entire book to vent his outrage. Published in 1956, Cross-Currents is an attack against McCarthy.

A good clue to understanding Forster’s mindset is his astonishing statement that “The civilized world was more revolted by McCarthyism than by Communism.” (p. 171) In Forster’s view, the millions of victims of Communism cannot compare to the trauma caused by asking a few dozen people if they had ever supported the Communist Party. What rational person, one must wonder, could really believe that the “civilized world” found the McCarthy hearings to be worse than several decades of mass murder! What can explain such a mentality?

Blacklisting

Whatever the reality of Forster’s complaint of blacklisting by an unspecified group of un-named anti-Communists, it’s worth noting that others have been victims of this practice.

Lillian Gish, one of America’s most acclaimed actresses, reported that she was blacklisted for a time from both screen and stage because of her support for the anti-interventionist America First Committee. She also related that she was promised a $65,000 film contract if she would resign from the Committee (without, of course, revealing that she was being bribed to do so).

Ayn Rand, the libertarian novelist who had also worked in Hollywood as a script writer, pointed out that during the Congressional investigations of Communists in the motion picture industry:

Everyone who has testified for the [Congressional] Committee – not the big stars, but the lesser-known actors and writers who were considered dispensable, and those who were free-lancing and were not under contract to a major studio – lost their jobs. Morrie Ryskind had more work than he could handle; he never again worked in Hollywood. Adolph Menjou, who was also free-lancing, got fewer and fewer jobs; after about a year, he could find no work at all. I was not victimized, because of The Fountainhead, and because I had a contract with Hal Wallis.

Interestingly, Rand (who was Jewish) used some of her time before the House Committee to lecture the lawmakers about why America should have avoided getting involved in war on the side of the Soviet Union, the regime she had fled. Forster, of course, is utterly unconcerned about the blacklisting of people like Gish, Ryskind or Menjou, apparently because they held views different than his own.

Hatred of Peace Activists

Forster reserves his most venomous words for the Americans who opposed US involvement in the Second World War. His portrayal of this mass movement is vicious and inaccurate. However much one might disagree with their view on this issue, the millions of Americans who opposed US intervention in the European war were unquestionably sincere in their conviction that this policy served the best interests of both the United States and humanity. Non-interventionists upheld a tradition that has a long and venerable place in American history.

By far the largest and most prominent anti-war group was the America First Committee. During its 15 months of life in 1940 and 1941, it enrolled more than 800,000 members, attracted thousands to mass rallies, and distributed millions of pamphlets and leaflets. Its broad-based membership included conservatives, liberals like Chester Bowles, and socialists of the stature of Norman Thomas.

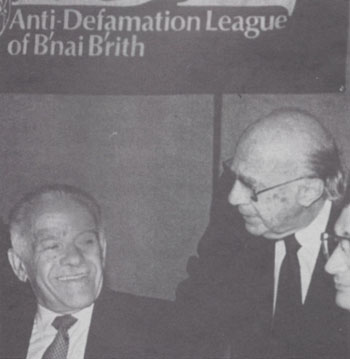

Forster with Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir at an ADL meeting in New York City, June 1988. At the right, barely visible, is the current National Director of the ADL, Abraham Foxman.

But Forster, official of a supposed anti-defamation organization, slanderously equates such people with anti-Semites and Nazis. Opposition to Roosevelt’s campaign for war, which included secret and plainly illegal measures, is castigated by Foster in the most vicious and simplistic way. “The pro-Nazi, anti-British, Roosevelt-hating, anti-Jewish propaganda was the same,” he writes. (p. 47) America First “was ultimately an anti-British, pro-German, anti-Soviet, anti-Semitic” movement that “had become the central propaganda weapon for isolationists, pro-Nazis and anti-Semites.” (pp. 75, 76).

Forster’s characterization is a lie. The America First Committee included many who were pro-British and pro-Jewish, but who simply opposed direct United States involvement in war. The America First leadership scrupulously strove to keep out anyone who obviously pro-Nazi or anti-Jewish. Members had to sign a pledge that they did not belong to a pro-Nazi or a Communist group. There is no evidence that the Committee, which counted Jews as members, was anti-Semitic. So scrupulous was the Committee that it refused a $250,000 donation from Henry Ford because of his previous association with anti-Jewish publications, even though Ford had publicly repudiated those works.

After writing that “bigots often were found in high places” (p. 56), Forster mentions as examples prominent anti-interventionists, including Montana Senator Burton K. Wheeler, North Dakota Senator Gerald P. Nye, and New York Congressman Hamilton Fish.

Charles Lindbergh

In his hateful attack against the anti-war movement, Forster takes special aim at Charles Lindbergh, the aviator who was the America First Committee’s most popular speaker and prominent spokesperson. (pp. 75–76). Writes Forster:

Lindbergh blamed the Jews for most of America’s foreign problems and described Franklin D. Roosevelt, the British and the Jews as enemy confederates in an international conspiracy. By his attack in a September 1941 Des Moines speech on Roosevelt, Jews, the British and internationalists for allegedly bringing on World War II, Lindbergh revealed the platform of the America First Committee.

If there were a contest for distorting as many facts as possible in a single paragraph, this one would be a top contender. Lindbergh never blamed “the Jews” for “most of America’s foreign problems,” nor did he claim that Roosevelt, the British and the Jews were “enemy confederates in a international conspiracy.” To show how Forster distorts historical truth for his own polemical purposes, it is worth recalling Lindbergh’s precise words in that speech of September 11, 1941:

The three most important groups who have been pressing this country toward war are the British, the Jewish, and the Roosevelt Administration. Behind these groups, but of lesser importance, are a number of capitalists, anglophiles, and intellectuals, who believe that their future, and the future of mankind, depend upon the domination of the British Empire. Add to these the Communistic groups who were opposed to intervention until a few weeks ago, and I believe I have named the major war agitators in this country.

Not a single word of the statement is untrue, and not a word is anti-Jewish. While it is true that Jews did, as a whole, strongly support American involvement in the European conflict, Lindbergh made no mention of any “conspiracy.” He never claimed that Roosevelt, the British or the Jews had started the war. Indeed, he made no mention whatsoever of the war’s origins.

Further remarks by Lindbergh in this same speech that show admiration for the Jews, and sympathy for their plight, are invariably ignored by anti-anti-Semites such as Forster. Because they are essential to understanding the larger context, they are worth quoting here:

It is not difficult to understand why Jewish people desire the overthrow of Nazi Germany. The persecution they suffered in Germany would be sufficient to make bitter enemies of any race. No person with a sense of dignity of mankind can condone the persecution of the Jewish race in Germany. But no person of honesty and vision can look on their pro-war policy here today without seeing the dangers involved in such a policy, both for us and for them.

Instead of agitating for war, the Jewish groups on this country should be opposing it in every possible way, for they will be among the first to feel its consequences. Tolerance is a virtue that depends upon peace and strength. History shows that it cannot survive war and devastation. A few far-sighted Jewish people realize this, and stand opposed to intervention. But the majority do not. Their greatest danger to this country lies in their large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio, and our government.

I am not attacking either the Jewish or the British people. Both races, I admire. But I am saying that the leaders of both the British and Jewish races, for reasons which are understandable from their viewpoint as they are inadvisable from ours, for reasons which are not American, wish to involve us in the war. We cannot blame them for looking out for what they believe to be their own interests, but we also must look out for ours. We cannot allow the natural passions and prejudices of other peoples to lead our country to destruction.

Although these are hardly the words of a Jew-hating Nazi, the propagandists of the pro-war movement immediately seized upon a small (and factual) portion of this speech, twisting what Lindbergh actually said, and distorting the truth so badly that much of the public was mislead. Using techniques that Forster and his colleagues at the ADL have mastered, numerous newspapers and politicians lashed out at Lindbergh, largely succeeding in blackening his reputation.

Lindbergh actually anticipated the smear campaign that would come as a result of his words in this speech. He had prepared a paragraph concerning the attacks, but decided to delete it from the final speech:

I realize that tomorrow morning’s headlines will say “Lindbergh attacks Jews.” The ugly cry of anti-Semitism will be eagerly joyfully pounded upon and waved about my name. It is so much simpler to brand someone with a bad label than to take the trouble to read what he says. I call you people before me tonight to witness that I am not anti-Semitic nor have I attacked the Jews.

Lindbergh’s remark about those who find it “so much simpler to brand someone with a bad label than to take the trouble to read what he says” might well refer to Forster and the ADL crowd.

The Eichmann Case

More than ten percent of this book is devoted to a chapter on the Eichmann case. Forster takes pains to defend Israel’s handling of the case, and to stoking the Holocaust flames.

During the Second World War, Adolf Eichmann had served as the SS officer responsible for co-ordinating the deportation of European Jews. He avoided capture at the end of the war, and escaped to Argentina. He lived quietly there until May 1960, when Israeli agents kidnapped him and took him to Israel where, after a highly-publicized trial, he was executed in 1962.

Even though Israel had an extradition treaty with Argentina, it made no effort to have Eichmann legally apprehended. Instead, Israeli secret agents seized him on the street, drugged him, and dispatched him to Israel in a waiting airplane. Eichmann had not committed any crimes in Israel, a country that did not exist when the acts for which he was tried took place. Consequently it had no legal jurisdiction in the case. But Israel claimed (and still claims) jurisdiction in such matters because it appropriates for itself the right to speak and act in the name of “the Jewish people,” wherever they live.

In most civilized countries, a person is put on trial to determine his guilt or innocence. Not in this case. Forster explains (pp. 200, 211) the reason for this highly-publicized trial:

The purpose of the trial? Israel stated the trial’s purpose was to alert the world’s conscience to the fearful consequences of totalitarianism. The most terrible, Israel said, is genocide. Its chief victims in modern history – although not the only ones – have been Jews… The hope is that the trial will serve as an effective educational weapon to assure that it never happens again.

One of the main reasons for this trial, which inevitably is tearing open so many deep wounds for so many people in Israel, is the government’s wish to teach its own young and the youth of the world the evil of Nazism and to remind the rest of us what an incredible price has to be paid by humanity to rid the earth of Hitlerism…

Serving as judges in the trial (which is similar in some ways to the trial, many years later, of John Demjanjuk) were three Israelis “of German-Jewish background.” As Forster admits, these men were “not, in the deepest recesses of their hearts, neutral. Impossible. Who can be neutral about the bestial murder of six million innocents?” (pp. 208, 209)

Forster responds (p. 203) to the accusation that Eichmann was tried and executed on ex post facto charges:

Wasn’t Israel trying Eichmann under an ex post facto law? An ex post facto statute is a law that makes an act criminal after the act itself was committed. True, it is outlawed in American jurisprudence. But the ex post facto concept is American, based on the idea that it is unfair to compel a man to stand trial for a deed which he could not have known was a violation of law when he committed it. Obviously, this concept cannot apply to murder; no one needs formal notice it is morally, legally and ethnically wrong to kill another person without justification.

There are several problems with Forster’s glib explanation. For one thing, ex post facto is not merely an American concept; it was a principle, for example, of Roman law: No crime without a law.

Furthermore, Eichmann was not (at least not specifically) ever charged with murder. Of the 15 counts brought against him by the Israelis, “four [were] based upon crimes against the Jewish people, seven for crimes against humanity, one for a war crime, and three for belonging to Nazi organizations.” (p. 205) Does Forster seriously ask us to believe that being tried in Israel in 1961 for belonging to an organization in Europe during the 1940s is not an ex post facto case?

In a murder charge the defendant is normally accused of killing a specific person or persons, who are usually named (unless the victim cannot be identified). Evidence is then presented to directly link the defendant to the murder of the specified person. In the Eichmann case, this was not done.

Mossad ‘Source’

One of Forster’s most startling revelations is his acknowledgment (p. 187), that in the Eichmann case he served as a “source” for Israel’s foreign espionage agency:

Among other Israeli intelligence operations, the Mossad – an acronym for the Hebrew name of the undercover service assigned to operate abroad – constantly sought leads from reliable governments and from other contracts and sources. I was a source.

Unfortunately, that’s all Forster tells us about this. He doesn’t reveal the extent or the duration of his service to the Mossad, or if (or how much) he was paid. Still, the bit he does acknowledge here may already be enough to confirm that he acted in violation of US federal law.

Illegal Activities

Forster acknowledges with some pride that the ADL, with his approval, has used illegal and unethical methods to gain information about political enemies. One ADL target of such activities, Forster relates, was Joseph Kamp (who died in June 1993, at the age of 93). A well-to-do man with important “connections,” Kamp’s work as head of the “Constitutional Education League” and as editor of The Awakener newsletter greatly annoyed Forster and the ADL. Kamp’s great sin, Forster charges, was to endlessly repeat that America was threatened by Communists and foreigners, “especially those with Jewish names.” He also sinned by calling the ADL a “low racket which promotes hate and breeds intolerance.” (pp. 62, 63)

As a result, the ADL was eager

to know as much as possible about his work. Our investigator was adept enough to make himself a good “friend” of Kamp. He had worked for both British and French intelligence and at the outset of the World War Two had served as an instructor in an American intelligence school.

One day, while Kamp was away, the ADL agent illegally entered Kamp’s Connecticut home, and made photographic copies of his files, particularly “material that divulged the identity of his financial contributors, network operations, and domestic and foreign connections utilized in his propaganda work.” (p. 63).

Although the agent was almost caught when Kamp returned home briefly to retrieve a few items, this mission in what Forster calls “the business of espionage” (p. 64) was a success. “… The Kamp caper was repeated by still another [ADL] field investigator under only slightly different circumstances,” Forster reports.

Forster tells about another ADL agent named Marjorie Lane (p. 64), who had lied to obtain a job working for a right-wing women’s organization. One night she and another ADL operative spent several hours in the office busy photographing all the documents they could lay hands on from the private files.

As revelations from the still-unfolding Gerard/Bullock case suggest, criminal “capers” are a long-standing tradition with the ADL. One is justified in assuming that the cases that have come to light are only the tip of the iceberg.

Valuable Exposé

This memoir concludes with a solemn observation that, in spite of prodigious efforts, anti-Semitism can still be found everywhere. (This is hardly surprising, because Forster “finds” anti-Semitism even where it does not exist.) But there is a silver lining in the cloud. “We may be back to Square One. Except for one player – Israel.” (p. 412). Arguably, though, a major generator of anti-Jewish sentiment during the last four decades has been Israel itself – or rather the Zionist state’s often outrageous activities.

Contrary to what the author intended, this revealing book by a high-ranking ADL official serves as valuable exposé of the moral character of a man who sanctions violence against political opponents, who spits on the First Amendment, uses illegal methods to obtain information about adversaries, and who served as an agent for a foreign spy agency.

Over the years, I have read several tracts and articles designed to discredit the Anti-Defamation League. None was able to persuade me of the illicit nature of this organization; it took the memoir of Arnold Forster to do that.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Journal of Historical Review, vol. 13, no. 6 (November/December 1993), pp. 39-46

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a