Rudolf Hess: Wronged Prisoner of Peace

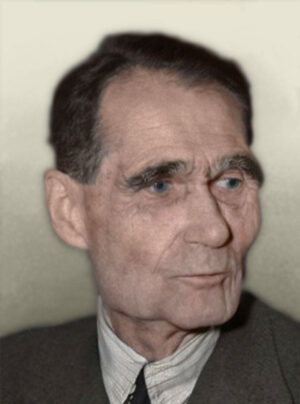

Rudolf Hess (1894-1987) was one of the most popular National Socialist leaders. Albrecht Haushofer, who was one-quarter Jewish and abhorred National Socialism, wrote in 1934 about Hess:[1]

“There is a strange charm in his personality; whenever he is there, a friendly veil falls over all the grey and black of the present.”

After meeting Hitler’s inner circle for the first time on April 13, 1926, Joseph Goebbels wrote about Hess in his diary:[2]

“Hess—the most decent person, quiet, friendly, reserved: the private secretary.”

Hess is also famous for his flight to Great Britain on May 10, 1941 to attempt to negotiate peace with the British. This article discusses Hess’s motives for this dangerous flight, the injustice against Hess at the Nuremberg Trial, and whether Hess committed suicide or was murdered in Spandau Prison.

Early Years

Rudolf Hess was born in the English-held city of Alexandria, Egypt, where his education began in 1900 at a German school. Hess left Egypt in 1908 to attend school in Godesberg, Germany. Upon graduation, Hess followed his father’s wishes and joined the family business.[3]

Hess voluntarily joined the First Bavarian Infantry Regiment with the outbreak of World War I. He was wounded in action in December 1916, and was seriously wounded in the lungs the following year. After a period of convalescence, Hess was commissioned with the rank of lieutenant, serving in the ill-fated List Regiment. In 1918 Hess volunteered to join the Imperial Flying Corps, where he flew a few operational flights in November before an armistice ended the war.[4]

Like many Germans, Hess was deeply disappointed by the inglorious way the war ended. The social and political upheaval in postwar Germany greatly affected Hess. He faced a Germany subject to mob-rule, and it seemed that certain regions in Germany might turn communist. During the spring of 1919, Bavaria for a while had a communist state government, and Hess took part in the street fighting which led to its overthrow. Hess was wounded in one leg in this fighting on May 1, 1919.[5]

Hess became convinced there were subversive elements at work in Germany. He read extensively about the situation and concluded that Germany had been brought to its knees by an international conspiracy of Jews and Freemasons.[6] Hess enrolled in the University of Munich, where he was introduced to Karl Haushofer, a major general who was starting a lecture series on geopolitics. Haushofer taught Hess that through an understanding of geopolitics, Germany could overcome its burden of war guilt and emerge again as a great nation. Hess regarded Haushofer as a second father, and Haushofer more or less adopted Hess as his third son.[7]

Hess and Haushofer first met Adolf Hitler one night in 1920 at a beer hall meeting. Hess was transfixed by Hitler’s two-hour speech. Hess joined the National Socialist German Workers’ Party and became convinced that Hitler was the future of Germany. Over the next several months Hess hedged his bets and kept close to both Haushofer and Hitler. However, Hess soon became Hitler’s best friend and one of his most devoted followers.[8]

Rise to Power

Hess was convinced Hitler could break the chains of the Versailles Treaty and lead Germany to a better future. Hitler’s first attempt to gain power occurred on November 9, 1923 in his ill-fated attempt to overthrow the government in Munich. Hess arrested three ministers of the Bavarian state government in the course of this unsuccessful putsch. Hitler was punished with imprisonment in the Landsberg Prison for his role in the coup attempt. Hess later joined Hitler in Landsberg Prison.[9]

It was during their time of incarceration that Hitler and Hess established their special relationship of trust and mutual confidence. It was also in Landsberg Prison that Hitler wrote his seminal work, Mein Kampf. Hess edited the pages of this book and checked them for errors. After Hitler was released early from prison on December 20, 1924, Hess became Hitler’s private secretary in April 1925.[10]

Hitler and Hess spent the summer of 1925 proofreading Mein Kampf, and by autumn the first volume was published. Although most readers were bored by this 400-page book, Hitler and Hess immediately set to work on a second volume. Hess remained Hitler’s closest confidant and advisor. Based partly on Hitler’s suggestion, Hess married Ilse Pröhl on December 27, 1927. Hess, Hitler’s private secretary who held no official post, had by 1931 become one of the most powerful and influential members of the National Socialist Party.[11]

Hitler asked Hess to attend all important meetings, introducing Hess in these meetings as one of his “closest colleagues and confidants.” Hess also performed the important function of raising money for the National Socialist Party. Hess succeeded in convincing the industrialist Fritz Thyssen to donate almost a million marks to the party, and also raised money from Otto Kirdorf, the wealthy director of a huge coal syndicate. In short, Hess was involved in numerous aspects of the party’s activities.[12]

Hess even developed what became the customary National-Socialist greeting and departure line: “Heil Hitler.” Also, unlike other close associates of Hitler, Hess never exploited power for himself. Everything Hess did was for Hitler.[13]

Hitler appointed Hess as Deputy Führer of the National Socialist Party on April 21, 1933. Hess’s job was to uphold its national and social principles and lead the governing party as Hitler’s representative. Reich President Hindenburg—acting on Hitler’s proposal—appointed Hess as Reich Minister without Portfolio on December 1, 1933. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, Hess remained Hitler’s close confidant, and a man Hitler trusted without reservation.[14]

Peace Mission

Hitler had never wanted war with Great Britain. To Hitler, Great Britain was the natural ally of Germany and the nation he admired most. Hitler had no ambitions against Britain or her Empire, and all of the captured records solidly bear this out.[15]

Hitler was eager to make peace once Great Britain and France had declared war against Germany. However, Churchill and other British leaders rejected all of Hitler’s numerous peace offers. Hitler continued to search for a way to end war with Great Britain.

On May 5, 1941, Hitler and Hess met for four hours in the Reich’s Chancellory—alone, without secretaries or aides. After the marathon session, adjutant Alfred Leitgen said the two men emerged appearing particularly affectionate. Leitgen said:

“Hitler held Hess’s hand in his for minutes. They silently looked into each other’s eyes.”

Leitgen also recalled hearing snippets of the discussions such as the odd phrase “No problems at all with the airplane” and the names “Albrecht Haushofer” and “Hamilton.”[16]

On May 10, 1941, Hess flew an unarmed Messerschmitt 110 to Scotland to attempt to negotiate a peace settlement with Great Britain. Under cover of darkness, Hess successfully evaded British anti-aircraft fire and a pursuing Spitfire. Hess parachuted for the first time in his life, and sprained his ankle landing in a Scottish farm field. A surprised farmer found Hess and turned him over to the local Home Guard unit.[17]

At his request, Hess was taken to speak with the Duke of Hamilton on May 11, 1941. Hess told the Duke of Hamilton why he had flown to Scotland:[18]

“I am on a mission of humanity. The Führer does not want to defeat England and wants to stop fighting.”

Unfortunately, the British had no interest in negotiating with Hess. On May 16, 1941, Hess was transported late at night in great secrecy to the Tower of London, and spent the rest of the war in British captivity.[19]

Although Hitler and Hess both denied that Hess flew to Scotland with Hitler’s knowledge and approval,[20] the available evidence suggests that Hitler knew and approved of Hess’s mission. The relationship between Hess and Hitler was so close that one can logically assume that Hess would not have undertaken such an important step without first informing Hitler. Also, Hess was prohibited from speaking publicly about his mission during his later 40-year period of imprisonment in Spandau Prison. This “gag order” was obviously imposed because Hess knew things that, if publicly known, would be highly embarrassing to the Allied governments.[21]

German Gen. Franz Halder confirmed after the war that Hess flew to Scotland with Hitler’s knowledge and approval. In an interview at a detention center of the Twelfth Army group at Wiesbaden, Halder told his American interrogators that Hitler dispatched Rudolf Hess to inform the British of Hitler’s peace offer. Halder said:[22]

“The British ‘double-crossed’ Hitler, and informed Moscow of the nature of Hess’s mission.”

Many other people have concluded that Hess flew to Great Britain with Hitler’s full knowledge and approval. For example, Georg Bernhard wrote in The New York Times:[23]

“It is now apparent to everybody that Rudolf Hess flew to England with the full consent of Adolf Hitler. It was his job to bring peace between Germany and England.”

J. Bernard Hutton wrote, “Hess’s historic flight to Britain was made with Hitler’s full knowledge and approval.”[24] Willis Carto also wrote, “The evidence is strong that Hess risked his life for peace under orders from Adolf Hitler.”[25]

Nuremberg Trial

The prosecution at the Nuremberg Trial had difficulty building a case against Rudolf Hess. U.S. prosecutor Robert Jackson sent Erich Lipman of the Third U.S. Army to search Ilse Hess’s household for incriminating documents. After trawling through 60 boxes of Hess’s private and official correspondence, Lipman concluded that most of it would only advance Hess’s case, and not that of the prosecution. Lipman declared:[26]

“Frankly, I am rather impressed with the type of friends he [Hess] had and the manner in which he frowned upon favoritism, even in the cases of his own family.”

British historian David Irving writes about the difficulty in charging Hess with a crime:[27]

“He [Hess] had personally issued a circular telegram to all the gauleiters in November 1938 halting the outrages of the Kristallnacht. He had participated in none of the secret Hitler conferences in 1938 and 1939. As the British well knew, Hess had tried to stop the war and to end the bombing. He had left Germany before the attack on Russia in June 1941 and before the onset of what would in the 1970s become known as the Holocaust. There seemed little real reason to inscribe Hess’s name on any list of war criminals.”

Despite the difficulty of charging Hess with a crime, the indictment at the Nuremberg Trial charged Hess with all four criminal counts. Hess regarded the trial as a sham and paid little attention to its proceedings. Although Hess had hardly spoken during the trial, he delivered a memorable closing speech on August 31, 1946. With his speech broadcast around the world, Hess concluded:[28]

“To me was granted to work for many years of my life under the greatest son my country has brought forth in a thousand years of history. […] The time will come when I shall stand before the judgement seat of the Eternal. I shall answer unto Him, and I know that he will judge me innocent.”

Hess was convicted by the Nuremberg Tribunal on the single count of “crimes against peace” and sentenced to life imprisonment. Soviet Gen. Vasily Sokolovsky, a member of the four-man Allied Control Council in Berlin, attempted to obtain a death sentence for Hess instead of life imprisonment, arguing that Hess was “responsible for all the crimes committed by the Nazi regime.” The other Control Council members rejected Sokolovsky’s request.[29]

British historian A. J. P. Taylor wrote concerning the injustice of the Hess case:[30]

“Hess came to this country in 1941 as an ambassador of peace. He came with the…intention of restoring peace between Great Britain and Germany. He acted in good faith. He fell into our hands and was quite unjustly treated as a prisoner of war. After the war, we could have released him.

No crime has ever been proven against Hess…As far as the records show, he was never at even one of the secret discussions at which Hitler explained his war plans. He was of course a leading member of the Nazi Party. But he was no more guilty than any other Nazi or, if you wish, any other German. All the Nazis, all the Germans, were carrying on the war. But they were not all condemned because of this.”

It is ironic that Hess—the only defendant at Nuremberg who had risked his life for peace—was found guilty of “crimes against peace.” The life sentence given Hess by the judges at Nuremberg was an extreme perversion of justice.

Imprisonment

Rudolf Hess was imprisoned in West Berlin’s Spandau Prison in 1947. Regulations forbade prison officials from calling Hess by his name; he was addressed only as “Prisoner No. 7.” For the first 20 years of his imprisonment, Hess at least had the limited company of a few other Nuremberg defendants. However, with the release of Albert Speer and Baldur von Schirach in October 1966, Hess was the only prisoner in Spandau until his death 21 years later.[31]

After Hess became the only prisoner in Spandau, he told U.S. Lt. Col. Eugene Bird:

“I am an innocent man. I see no reason why I should not be turned loose. Even if I were guilty—which I am not—no other prisoner who has been sentenced to life or even death for their war crimes still remains in jail. I am the only one I know of who has not been freed. It is all wrong.”

However, the Russians would not consider freeing Hess.[32]

Hess’s Cell Number 7 in Spandau became the world’s most expensive single-bed accommodation. Including full board, the daily cost of this two by three-meter room was 2,800 deutschmarks. Hess was watched around the clock by three armed guards, 20 prison officials, 17 civilians, four doctors, one chaplain and four prison directors. Thus, the loneliest prisoner in the world sat behind bars, walls and barbed wire for an entire generation—costing the taxpayers of West Berlin and West Germany millions of deutsche marks.[33]

Hess died in Spandau Prison on August 17, 1987, allegedly by hanging himself in a summerhouse in the prison garden. Hess’s death was ruled a suicide. However, the idea that Hess committed suicide quickly unraveled. Dr. Hugh Thomas, a British military medic, wrote that the arthritic hands of Hess were far too weak for a suicide attempt. It would have been impossible for Hess to lift his hands above his head, let alone hang himself or tighten a noose. Dr. Thomas concluded that Hess had been strangled from behind with an electric cord.[34]

Abdallah Melaouhi, a medical aide at Spandau who became close friends with Hess, writes that on the day Hess died, Malaouhi was held up for 20 minutes at a locked door before he could see Hess. When he finally arrived on the scene, Melaouhi was convinced a struggle had taken place. All of the furniture had been overturned, and even the straw mat was out of place. The extension cord that Hess allegedly used to hang himself was plugged into the socket in the wall and still connected to the lamp. When Melaouhi arrived at the scene, American guard Anthony Jordan said to him:[35]

Melaouhi writes that he is convinced he could have saved Hess’s life if he had been promptly admitted through the main gate and allowed to take a straight route to the garden house. Melaouhi also states that the course of events that led to Hess’s alleged self-strangulation were impossible both technically and physically. He concludes that Hess did not commit suicide, but was instead murdered by British and American agents.[36]

An alleged suicide note written by Hess was discovered by the Allies two days after Hess’s death. This suicide note was later proven to be a crude hoax. Hess’s son Wolfgang concluded:[37]

“Rudolf Hess did not commit suicide on August 17, 1987, as the British government claims. The weight of evidence shows instead that British officials, acting on high-level orders, murdered my father.”

Conclusion

Winston Churchill wrote about Rudolf Hess after the war:[38]

“Reflecting upon the whole of this story, I am glad not to be responsible for the way in which Hess has been and is being treated. Whatever may be the moral guilt of a German who stood near to Hitler, Hess had, in my view, atoned for this by his completely devoted and fanatic deed of lunatic benevolence. He came to us of his own free will and, though without authority, had something of the quality of an envoy. He was a medical and not a criminal case, and should be so regarded.”

Churchill was being disingenuous when he said he was not responsible “for the way in which Hess has been and is being treated.” Not only did Churchill refuse to negotiate with Hess, but Churchill kept Hess incarcerated in Great Britain until the end of the war. Churchill also never used his considerable influence to attempt to keep Hess from being sent to the Nuremberg Trial.

Hess continues to be disrespected and subject to injustice after his death. Hess was not even allowed to stay buried in his chosen town of Wunsiedel. The town of Wunsiedel became the scene of pilgrimages for people who wanted to honor Hess for his courageous effort to negotiate peace with Great Britain. On July 20, 2011, Hess’s grave was reopened and his remains were exhumed and then cremated. His ashes were scattered at sea, and his gravestone, which bore the epitaph “I took the risk” was destroyed.[39]

Historian Mark Weber writes:[40]

“The injustice against Hess was not something that happened once and was quickly over. It was, rather, a wrong that went on, day after day, for 46 years. Rudolf Hess was a prisoner of peace and a victim of a vindictive age.”

Notes

| [1] | Douglas-Hamilton, James, Motive for a Mission: The Story Behind Hess’s Flight to Britain, London: MacMillan St. Martin’s Press, 1971, p. 51. |

| [2] | Schwarzwäller, Wulf, Rudolf Hess: The Last Nazi: Bethesda, Md.: National Press, Inc., 1988, p. 121. |

| [3] | Manvell, Roger and Fraenkl, Heinrich, Hess: A Biography, New York: Drake Publishers Inc., 1973, pp. 17-19. |

| [4] | Ibid., p. 19. |

| [5] | Ibid., pp. 19-20. |

| [6] | Schwarzwäller, Wulf, Rudolf Hess, op. cit., p. 15. |

| [7] | Kilzer, Louis C., Churchill’s Deception: The Dark Secret that Destroyed Nazi Germany, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994, pp. 83-84. |

| [8] | Ibid., pp. 93-94. |

| [9] | Hess, Wolf Rüdiger, “The Life and Death of My Father, Rudolf Hess,” The Journal of Historical Review, Vol. 13, No. 1, Jan./Feb. 1993, p. 27; https://codoh.com/library/document/the-life-and-death-of-my-father-rudolf-hess/. |

| [10] | Ibid. |

| [11] | Schwarzwäller, Wulf, Rudolf Hess, op. cit., pp. 115-119. |

| [12] | Ibid., pp. 118-119. |

| [13] | Kilzer, Louis C., Churchill’s Deception, op. cit, pp. 108-109. |

| [14] | Hess, Wolf Rüdiger, “The Life and Death of My Father, Rudolf Hess,” op. cit., p. 28. |

| [15] | Irving, David, Hitler’s War, New York: Avon Books, 1990, p. 3. |

| [16] | Kilzer, Louis C., Churchill’s Deception: op. cit, p. 275. |

| [17] | Weber, Mark, “The Legacy of Rudolf Hess,” The Journal of Historical Review, Vol. 13, No. 1, Jan./Feb. 1993, p. 20; https://codoh.com/library/document/the-legacy-of-rudolf-hess/. |

| [18] | Langer, Howard J., World War II: An Encyclopedia of Quotations, Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1999, p. 142. |

| [19] | Douglas-Hamilton, James, Motive for a Mission: The Story Behind Hess’s Flight to Britain, London: MacMillan St. Martin’s Press, 1971, pp. 175, 182-189. |

| [20] | Bird, Eugene K., Prisoner #7: Rudolf Hess, New York: The Viking Press, 1974, p. 202. |

| [21] | Hess, Wolf Rüdiger, “The Life and Death of My Father, Rudolf Hess,” op. cit., pp. 29, 31. |

| [22] | Kilzer, Louis C., Churchill’s Deception: op. cit, pp. 72-75. |

| [23] | Ibid., p. 55. |

| [24] | Hutton, J. Bernard, Hess: The Man and His Mission, New York: The MacMillan Company, p. 21. |

| [25] | Melaouhi, Abdallah, Rudolf Hess: His Betrayal and Murder, Washington, D.C.: The Barnes Review, 2013, p. 7. |

| [26] | Irving, David, Nuremberg: The Last Battle, London: Focal Point Publications, 1996, p. 148. |

| [27] | Ibid., p. 29. |

| [28] | Ibid., pp. 144, 255. |

| [29] | Ibid., pp. 280, 284-285. |

| [30] | Sunday Express, London, April 27, 1969. |

| [31] | Weber, Mark, “The Legacy of Rudolf Hess,” op. cit., pp. 22-23. |

| [32] | Bird, Eugene K., Prisoner #7: Rudolf Hess, New York: The Viking Press, 1974, p. 152. |

| [33] | Schwarzwäller, Wulf, Rudolf Hess, op. cit., pp. 13-14. |

| [34] | Melaouhi, Abdallah, Rudolf Hess, op. cit., pp. 152-154. |

| [35] | Ibid., pp. 120, 128-129. |

| [36] | Ibid., pp. 35, 130-131, 135. |

| [37] | Hess, Wolf Rüdiger, “The Life and Death of My Father, Rudolf Hess,” op. cit., pp. 38-39. |

| [38] | Churchill, Winston S., The Grand Alliance, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950, p. 55. |

| [39] | BBC News Europe, July 21, 2011. |

| [40] | Weber, Mark, “The Legacy of Rudolf Hess,” op. cit., p. 23. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, Vol. 13, No. 3

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a