The Holocaust before It Happened

A Review

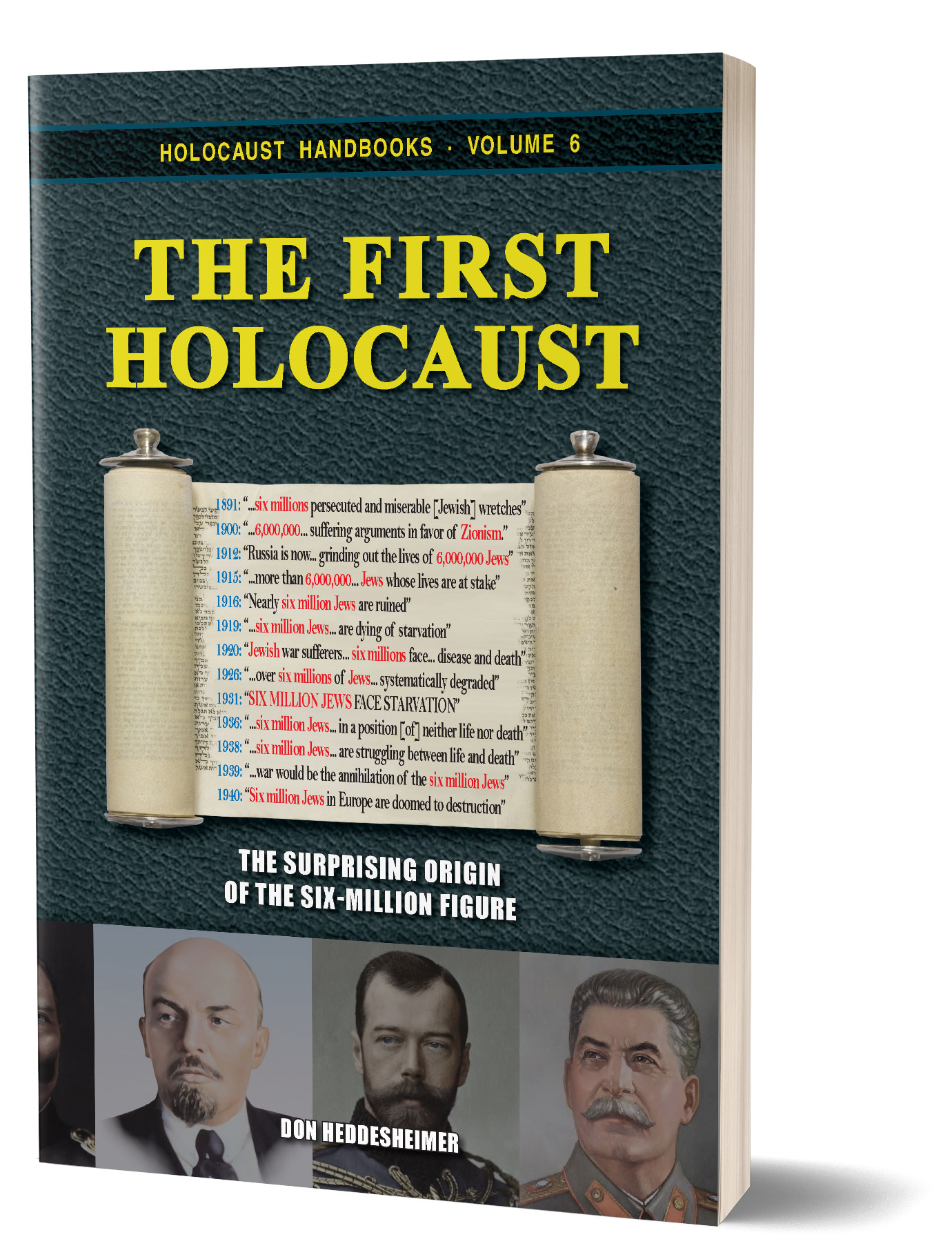

Don Heddesheimer, The First Holocaust: Jewish Fundraising Campaigns with Holocaust Claims during and after World War One, Theses & Dissertations Press, Chicago 2003, pb., 140 pp., $9.95.

George Santayana was famous for his aphorism “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Perhaps those who believe in the myth of the ‘six million’ have forgotten that Jews were making substantially similar claims regarding ‘six million’ Jews about to perish in the aftermath of World War One.

Don Heddesheimer has written a fascinating account of these claims in The First Holocaust: Jewish Fundraising Campaigns with Holocaust Claims during and after World War One. Again and again the pages of the New York Times and other journals were filled with allegations that Jews in Poland and other war-torn countries, all ‘six million’ of them, were threatened with imminent extinction through starvation and disease unless large sums of money were raised and sent overseas. As a matter of fact there was much starvation and disease in Germany and other war-ravaged lands but it did not primarily affect the Jews. Rather, as numerous American military and diplomatic personnel observed, the common people suffered while wealthy Jews lived high on the hog. Then as now, Jews sought to elevate their suffering above that of all others.

Heddesheimer establishes that despite much hand wringing over real and alleged suffering the bulk of the money for Jewish relief actually went to “constructive undertakings” – meaning such things as establishing cooperative banks in Poland, financing tradesmen and artisans, and, in particular, promoting Jewish agricultural settlements. It should be emphasized that this Jewish fundraising was conducted within the context of three key concurrent historical events: 1) the communist revolution in Russia; 2) the rise of Zionism in Palestine together with the incipient Palestine Mandate; and 3) the effort to secure ‘minority rights’ (better, Jewish rights to a state within a state) in anti-Semitic Eastern Europe. Thus, Jewish relief served as camouflage for much broader political objectives.

Much of the money was channeled through the Joint Distribution Committee, an organization which still exists today. The Joint Distribution Committee was charged by many informed American diplomats and military men, such as Hugh Gibson, the U.S. ambassador to postwar Poland, with involvement in supplying the Bolsheviks (an activity that would have been facilitated by the fact that most Polish Bolsheviks were Jewish, according to Gibson). Such wealthy American Jews as Felix Warburg of the Kuhn-Loeb bank in New York helped finance Jewish agricultural colonies in Soviet Russia with the cooperation of the Soviet government. By 1928 there were 112 Jewish agricultural settlements in the Crimea alone.

Two organizations, in particular, were involved in the Soviet-Jewish collaboration: the aforementioned Joint Distribution Committee, and the American Jewish Joint Agricultural Corporation – the so-called Agri-Joint, to which Julius Rosenwald, the owner of Sears, was a generous donor. Heddesheimer does an excellent job of putting this collaboration in proper historical context. He points out that many of these Jewish agricultural colonies were Zionist and were intended as training centers for eventual transfer to Palestine. He also makes clear the interrelatedness of the Zionist and communist movements by referring to several significant facts that have been largely forgotten. Thus, he quotes or paraphrases Dov Ber Borochov’s The National Question and the Class Struggle, in which the Zionist desire for a Jewish state in Palestine was represented as a Marxist struggle by an oppressed nationality for its own autonomy. Heddesheimer also cites Nahum Sokolow on how, during the 1917 Communist uprising in the port of Odessa, entire battalions of Jewish revolutionaries marched in the streets behind banners proclaiming “Liberty in Russia, Land and Liberty in Palestine!“

There is a saying that “The more things change, the more they remain the same.” This is the basic message of The First Holocaust. The essential elements of the post-World War II charge of the virtual annihilation of East European Jewry are already present in the post-WWI claim of the impending starvation of the ‘six million.’ The only significant difference is the addition of the gassing claim twenty-five years later. Yet The First Holocaust does more than merely trace the antecedents of the latter extermination accusation. It demonstrates that organized Jewish power was already both massive and ominous even before World War One, able to achieve, for one, the abrogation of the longstanding trade treaty between the United States and tsarist Russia through pressure brought on the U.S. government almost entirely by Jews.

At 140 pages, The First Holocaust is a compact book, but it packs an enormous amount of thought-provoking data into a highly informed historical context. Scholars of the Holocaust and of the Jewish question will learn almost as much from The First Holocaust as will interested laymen.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Revisionist 2(1) (2004), pp. 104f.

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a