The Myth of the Big Business-Nazi Axis

The party-line of the Left is that Fascism and Nazism were the last resort of Capitalism.[1] Indeed, the orthodox Marxist critique does not go beyond that. In recent decades there has been serious scholarship within orthodox academe to understand Fascism as a doctrine. Among these we can include Roger Griffin,[2] Roger Eatwell,[3] and particularly Zeev Sternhell.[4] The last in particular shows that Fascism derived at least as much from the Left as from the Right, emerging from Italy but also in particular from Francophone Marxists as an effort to transcend the inadequacies of Marxism as an analysis of historical forces.

Among the National Socialists in Germany, opposition to international capital figured prominently from the start. The National Socialists, even prior to adopting that name, within the small group, the German Workers’ Party, saw capital as intrinsically anti-national. The earliest party program, in 1919, stated that the party was fighting “against usury […] against all those who make high profits without any mental or physical work,” the “drones” who “control and rule us with their money.” It is notable that even then the party did not advocate “ socialization” of industry but profit-sharing and unity among all classes other than “drones.”[5] As the conservative spokesman Oswald Spengler pointed out, Marxism did not wish to transcend capital but to expropriate it. Hence the spirit of the Left remained capitalist or money-centered.[6] The subordination of money to state policy was something understood in Germany even among the business elite, and large sections of the menial class; quite different to the concept of economics understood among the Anglophone world, where economics dominates state policy.

Hitler was continuing the tradition of the German economic school, which the German Workers’ Party of Anton Drexler and Karl Harrer had already incorporated since the party’s founding in 1919. Hitler wrote in 1924 in Mein Kampf that the state would ensure that “capital remained subservient to the State and did not allocate to itself the right to dominate national interests. Thus, it could confine its activities within the two following limits: on the one side, to ensure a vital and independent system of national economy and, on the other, to safeguard the social rights of the workers.” Hitler now realized the distinction between productive capital and speculative capital, from Feder who had been part of a political lecture series organized by the army. Hitler then understood that the dual nature of capital would have to be a primary factor addressed by any party for reform.[7] The lecture had been entitled “The Abolition of Interest-Servitude.”[8] A “truth of transcendental importance for the future of the German people” was that “the absolute separation of stock-exchange capital from the economic life of the nation would make it possible to oppose the process of internationalization in German business without at the same time attacking capital as such […].”[9] While Everette Lemons, apparently a libertarian, quotes this passage from Mein Kampf, he claims that Hitler loathed capitalism, whether national or international. As illustrated by the passage above, Hitler drew a distinction between creative and speculative capital, as did the German Workers’ Party before he was a member.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R98364 / CC-BY-SA [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons

“I would indicate, as the distinguishing characteristic of my system, NATIONALITY. On the nature of nationality, as the intermediate interest between those of individualism and of entire humanity, my whole structure is based.”

It was an aim that German businessmen readily embraced.

Because the Hitler regime would not or could not fulfill the entirety of the NSDAP program, and because Feder was given a humble role as an under-secretary in the economics ministry, there is a widespread assumption that the regime was a tool of big capital. The Marxist interpretation of the Third Reich as a tool of monopoly capital has been adopted and adapted by their opposite number, libertarians, particularly aided by the book of the Stanford research specialist Dr. Antony Sutton. Sutton followed up his Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution,[12] detailing dealings between U.S. and other business interests and the Bolshevik regime, with Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler.[13] Many libertarians welcome the second book as showing that Hitler was just as much a “socialist” as the Bolsheviks and that both had the backing of the same big-business interests that pursue a “collectivist” state. Lemons, for example, argues that Hitler’s anti-capitalism was an implementation of many of the ideas in Marx’s Communist Manifesto, thereby indicating an ignorance of German economic theory.[14] Lemons refers to Hitler’s “communist style” economy.[15]

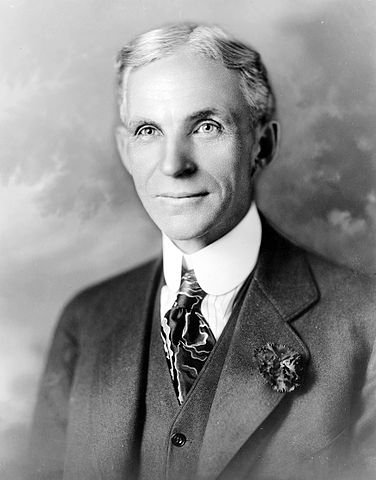

Henry Ford – an Early Nazi Party Sponsor?

If there was any wealthy American who should or could have funded Hitler it was Henry Ford Sr. Indeed, Ford features prominently in allegations that Hitler received financial backing from wealthy elites. But Ford was not part of the financial elite. He was an industrialist who challenged Wall Street. If he had backed Hitler that would have been an example of a conflict between “industrial capital” and “financial capital” that Ford had himself recognized, and that Hitler had alluded to in Mein Kampf. Not only did his newspaper the Dearborn Independent, under the editorship of W. J. Cameron, run a series of ninety-one articles on the “Jewish question,” but that series was issued as a compendium called The International Jew, which was translated into German. Such was the pressure from Jewish Wall Street interests on the Ford Motor Company that Ford recanted, and falsely claimed that he had not authorized the series in his company newspaper.[16] Yet Ford never funded the Hitlerites, despite several direct, personal appeals for aid on the basis of “international solidarity” against Jewish influence.

Sutton did an admirable job of tracing direct and definitive links between Wall Street and the Bolsheviks. However, perhaps in his eagerness to show the common factor of “socialism” between National Socialists and Bolsheviks, and the way Wall Street backed opposing movements as part of a Hegelian dialectical strategy,[17] Sutton seems to have grasped at straws in trying to show a link between plutocrats and Nazis. Sutton repeats the myth of Ford backing of the Hitlerite party that had been in circulation since the 1920s. As early as 1922 The New York Times reported that Ford was funding the embryonic National Socialist party, and the Berliner Tageblatt called on the U.S. ambassador to investigate Ford’s supposed interference in German affairs.[18] The article in its entirety turns out to be nothing but the vaguest of rumor-mongering, of making something out of nothing at all, but it is still found to be useful by those perpetrating the myth of big-money backing for Hitler.[19] Dr. Sutton quotes the vice president of the Bavarian Diet, Auer, testifying at the trial of Hitler after the Munich Putsch in February 1923, that the Diet long had had information that Hitler was being financed by Ford. Auer alluded to a Ford agent seeking to sell tractors having been in contact with Dietrich Eckart in 1922, and that shortly after Ford money began going to Munich.[20] Having provided no evidence whatsoever, Sutton states that “these Ford funds were used by Hitler to foment the Bavarian rebellion.”[21]

By Hartsook, photographer. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“I intended to write my book solely concentrating on the patriotism of Ford and General Motors during World War II but my plans were altered causing me to emphasize how Marxist ideology combined with sensationalism has smeared Ford and GM. The book was conceived as a PhD in history dissertation for Central Michigan University. Almost from its inception my advisor, Eric Johnson,[23] attempted to force me to libel the Ford Motor Company. He ordered me to accuse Ford of betraying the United States during World War II using falsehoods based on the faulty implications of sensationalist journalists.”

What these accounts of the funding of the Nazi party and even of the Third Reich war machine amount to are descriptions of interlocking directorships and the character of what is today called globalization. Hence, if Ford, General Electric, ITT, General Motors, and Standard Oil are somehow linked to AEG, I. G. Farben, Krupp, etc., it is then alleged that Rockefeller, Ford, and even Jewish financiers such as James Warburg, were directly involved in a conspiracy to aid Nazi Germany. To prove the connections, Sutton has a convenient table which supposedly shows “Financial links between U.S. industrialists and Adolf Hitler.” For example Edsel Ford, Paul M. Warburg and two others in the USA are listed as directors of American I.G. while in Germany I.G. Farben reportedly donated 400,000 R.M. to Hitler via the Nationale Treuhand; ipso facto Edsel Ford and Paul Warburg were involved in funding Hitler.[25] The connections do not seem convincing. They are of an altogether different character than the connections Sutton previously documented between Wall Street and the Bolsheviks.

The story behind the Henry Ford-Nazi legend has been publicly available since 1938. Kurt Ludecke had been responsible for attempting to garner funds for the fledgling Nazi party since joining in 1922. In 1934 he had fallen out with Hitler, had been incarcerated, and then left Germany for the USA, where he wrote his memoirs, I Knew Hitler.[26]He sought out possible funding especially in the USA, met Hiram Wesley Evans, Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, the organization, then 5,000,000 strong, impressing him as a good money-making racket for its recruiters, who got 20% commission on membership fees.[27] He met Czarist supporters of Grand Duke Cyril, claimant to the Russian throne, in Paris,[28] and in Britain several aristocrats suspicious of Jewish influence: the Duke of Northumberland, and Lord Sydenham.[29] Money was not forthcoming from any of them. Indeed, Ludecke traveled about perpetually broke.

Ludecke met Ford in 1922. He attempted to persuade Ford that international solidarity was needed to face the Jewish issue, and that the Hitler movement had the best chance of success. Ford could not relate to the political requirements and while listening had no interest in providing funds. It is evident from Ludecke that all of the party’s hopes had been pegged on Ford’s financial backing. Ford’s series on The International Jew was much admired in Nazi circles. Hitler also greatly admired Ford as an industrial innovator, a picture of the industrialist hanging up in Hitler’s office; something that is seen as of great significance to those seeking a Nazi connection.[30]

James Pool, on the subject of the funding of Hitler, spends thirty pages attempting to show that Ford might have given money to the NSDAP on the sole basis that he was anti-Jewish. He frequently cites Ludecke, but decides to ignore what Ludecke stated on Ford. Pool states that Frau Winifred Wagner had told him in an interview that she had arranged for Ludecke to meet Ford, which is correct, but it is evident that her claim that Ford gave Hitler money is pure assumption. Pool conjectures that the money was given by Ford to Hitler via Boris Brasol, an anti-Semitic Czarist jurist, who in 1918 had worked for U.S. Military Intelligence, and had who maintained contact with both the Nazi party and was U.S. representative for Grand Duke Cyril. Again Pool is making assumptions, on the basis that Brasol was employed by Ford. Pool’s “evidence” is the same as that used by Sutton; contemporary newspaper accounts of rumors and allegations.[31]

Had Ludecke succeeded in gaining funds from Ford that would not only have not been an example of funding from Wall Street and international finance, but it would have been an example of how not all wealthy individuals are part of the world’s banking nexus. Ford definitely was not, and drew a distinction between creative and destructive capital. Despite his ignominious surrender and groveling to Jewish interests when the pressure mounted due to his publication of The International Jew, in 1938 Ford described to The New York Times the dichotomy that existed between the two forms of capital:[32]

“Somebody once said that sixty families have directed the destinies of the nation. It might well be said that if somebody would focus the spotlight on twenty-five persons who handle the nation’s finances, the world’s real war makers would be brought into bold relief. There is a creative and a destructive Wall Street […I]f these financiers had their way we’d be in a war now. They want war because they make money out of such conflicts – out of the human misery such wars bring.

Sutton dismissed this, writing: “On the other hand, when we probe behind these public statements we find that Henry Ford and son Edsel Ford have been in the forefront of American businessmen who try to walk both sides of every ideological fence in search of profit. Using Ford’s own criteria, the Fords are among the ‘destructive’ elements.”[33] Contrary to Sutton, however, Pool states that Ford executives had been strongly opposed to their boss’s anti-Jewish campaign, and they persuaded him to drop the campaign in the late 1920s. In the forefront of this was his son, Edsel who owned 41% of the stock.[34]

Ford’s actions show that he was opposed to the forces of war. He did not do himself any favors by opposing the “destructive Wall Street.” In 1915 Ford chartered the Oscar II, otherwise known as the Ford “Peace Ship,” in the hope of persuading the belligerents of the world war to attend a peace conference. The mission received mostly ridicule. Those aboard, including Ford, were wracked with influenza. Ford continued to fund the “Peace Ship” as it traveled around Europe for two years, and despite the ridicule was widely regarded as a sincere, if naïve, pacifist. Dr. Sutton does not mention Ford’s “Peace Ship” or his peace campaign during World War I. Therefore, when he was an early supporter of the America First Committee,[35] founded in 1940 to oppose Roosevelt’s efforts to entangle the USA in a war against Germany, he was too easily dismissed as pro-Nazi, as was America First.[36] Very prominent Americans joined from a variety of backgrounds, including General Robert A. Wood, president of Sears Roebuck, and among the most active, aviation hero Charles Lindbergh. Socialist Party leader Norman Thomas was a regular speaker at rallies. Many Congressmen and Senators resisted the Roosevelt war machine. They included pacifists, liberals, Republicans, Democrats, conservatives. Of Henry Ford, George Eggleston, an editor of Reader’s Digest, Scribner’s Commentator, and formerly of Life, and a major figure in America First, recalled that so far from being a “Nazi,” Ford expressed the hope that there would be a “parliament of man,” “a world-wide spirit of brotherhood, and an end to armed conflict.”[37]

J. P. Morgan & Co. – Thomas Lamont

Thomas W. Lamont, senior partner in J. P. Morgan, was in the forefront of Wall Street agitation for war. Lamont, a supporter of Roosevelt’s New Deal, was a keen protagonist of internationalism. Speaking to the Academy of Political Sciences at the Astor Hotel in New York on 15 November 1939, he stated that the war against Germany was the consequence of the failure of the Versailles treaty and the rise of economic nationalism. In contrast to Old Guard Republicans such as ex-president Herbert Hoover, Lamont did not believe that it was possible to negotiate with Hitler. However, the military defeat of Hitler would not suffice. The USA must abandon isolationism and embrace “internationalism.”[38]

Lamont indeed had it right: international capital versus economic nationalism. The latter now included imperialism, and all autarchic trading blocs and empires. International finance could no longer be constrained by empires and trading blocs. But the world order that Woodrow Wilson had tried to inaugurate after World War I with his “Fourteen Points” and the League of Nations, based around international free trade, had been repudiated even by his own country.[39] The Axis states were building autarchic economic blocs, and had been instituting barter among states, including those that they had occupied. Roosevelt was to candidly state to Churchill during the discussions on the “Atlantic Charter” that the post-war world would not tolerate any empires including the British, and would be based on free trade. He stated unequivocally that the war was being fought over the premise of free trade.[40] Roosevelt stated to Churchill, as related by the president’s son, Elliott Roosevelt:[41]

“Will anyone suggest that Germany’s attempt to dominate trade in central Europe was not a major contributing factor to war?”

Apparently the cause of the war was not Pearl Harbor, nor the invasion of Poland. Roosevelt made it clear that international free trade would be the foundation of the post-war world, and empires would be passé.

General Motors – James D. Mooney

Another alleged enthusiast for Nazi Germany was James D. Mooney, vice president of General Motors, in charge of European operations. General Motors plays a large role in the alleged nexus between the Nazis and Big Business because of its European affiliates operating in German-occupied countries during the war. Such was Mooney’s supposed enthusiasm for Nazism that he allegedly regarded himself as a future “Quisling” in the USA in the event of a German victory.[42] The most extraordinary nonsense has been widely repeated that Mooney practiced how to technically achieve a Nazi salute and “Sieg Heil” in front of his hotel mirror prior to meeting Hitler in 1934. How Edwin Black knows this is not stated.[43]

It is evident that, utilizing his world-wide connections, Mooney embarked on private diplomacy with the intent of avoiding war. However, already in 1938 a G.M. executive, likely to have been Mooney, approached the British War Office to discuss British requirements in the event of war with Germany. From what is indicated by Mooney’s unpublished autobiography, it seems that, unsurprisingly, a major concern was the German method of trade. A biographer states of this:

Mooney took the opportunity at the dinner to deliver his own “blockbuster”: if the Germans could negotiate some form of gold loan, would they be willing to stop their subsidized exports and special exchange practices which were so annoying to foreign traders, particularly the U.K. and the U.S? Whilst Mooney clearly honestly believed that this might ensure peace, in truth the practices had had a deleterious effect on General Motor’s extraction of profit out of Germany….[44]

Mooney formulated a list of recommendations to ease tensions. Significantly, most of the list involves the return of Germany to the world trading and banking system:

- Limitation of armaments.

- Non-aggression pacts.

- Move into trade practices of western nations:

- Free exchange

- Discontinue subsidized exports

- Move into most-favored-nation practices.

- Discharge foreign obligations (pay debts).[45]

It seems evident that Mooney was acting as an emissary for international capital, if not also as an intelligence agent for the U.S.A. and/or Britain. Some efforts were made by Walther Funk of the Reichsbank to compromise on terms of trade and finance, but war intervened. On February 4, 1939 Mooney stated before an annual banquet of the American Institute of Banking that an accommodation with Hitler could not be reached.[46]

Reich Commissioner for the Handling of Enemy Property

Allied-affiliated corporations such as Opel, affiliated with General Motors, operating in German-occupied Europe during the war did so under control of the Reich Commissioner for the Handling of Enemy Property.

German state decrees of June 24 and 28, 1941 blocked the assets of American companies, following the blocking of German assets in the USA on June 14, 1941.

In a review for the U.S. National Archives. Dr. Greg Bradsher states that American company and bank assets were seized by a December 11, 1941 amendment to the “Decree Concerning the Treatment of Enemy Property of January 15, 1940.” U.S. corporate and bank assets were controlled by the Reichskommissar für die Behandlung Feindlichen Vermoegens, which was part of the Ministry of Justice. Such trusteeship was part of international law. The Reichskommissar acted as trustee for the property of enemy aliens, in accordance with the German war effort until the end of hostilities, after which they would be returned to the owners with proper accounting. A custodian was appointed for each enterprise, who rendered financial accounts to the Reichskomissar every six months. However, other enterprises were confiscated outright by the Reich Ministry of Economics.[47]

“By March 1, 1945, the Reichskommissar Office had taken under administration property in excess of RM 3.5 billion. On that date, the approximately RM 945 million of US property was administered by the Reichskommissar’s Office and another RM 267 million of US property was not administered by the Reichskommissar’s Office.”[48]

Therefore, foreign corporations were hardly free to pursue their profits during war-time. Communication with the home office of the corporation was discontinued. Nonetheless, the argument persists that such corporations as Ford and General Motors were in league with the enemy during the war.[49] On the basis that the same German directors of Opel in Germany prior to the war were approved by the Reich office during the war, and that Alfred P. Sloan and Mooney remained theoretically on the Opel board, this is deemed sufficient to show collusion.[50] While Dr. Bradsher is unsure as to what happened to the profits, according to the Dividend Law of 1934, corporations were restricted on the amount of profits and dividends payable to shareholders to 6%. The remainder of profits had to be reinvested into the enterprise or used to buy Government bonds.[51] In short, the foreign-affiliated corporations were run by and for Germany as one would expect, and according to the aim of national autarchy.

Dr. Sutton tries to resolve many contradictions and paradoxes by stating that they are part of a Hegelian dialectical process learned in Germany during the early 19th century by scions of Puritan finance who founded the Yale-based Skull and Bones Lodge 322.[52] Hence, the reason why sections of Big Business dealt with both National Socialist Germany and the USSR; they were promoting controlled conflict that would result in a dialectical globalist synthesis.[53]

Fritz Thyssen

Sutton quotes Fritz Thyssen as to why he supported Hitler, but does not see that the motives are different from Wall Street’s. Thyssen, and other industrialists such as Krupp, who funded Hitler, did so openly and for patriotic reasons. Thyssen wrote, as cited by Sutton:[54]

“I turned to the National Socialist party only after I became convinced that the fight against the Young Plan was unavoidable if complete collapse of Germany was to be prevented.”

The Young Plan for the payment of World War I reparations was regarded as the means of controlling Germany with American capital.[55] Thyssen is hardly an example of a nexus between Nazism and international capitalism; to the contrary, it shows that German business was motivated by patriotic sentiment to an extent that American business was not then and is today lesser still.

Thyssen was a Catholic motivated by the Church’s social doctrine that sought an alternative to both Marxism and monopoly capitalism. Like many others throughout the world of all classes, Thyssen found the corporatist doctrines of Fascism and National Socialism to reflect Church doctrine on social justice. Thyssen was a member of the conservative National People’s Party. While one of the few industrialists who donated to the NSDAP, at a late date, even this was meagre. The denazification trials in 1948 found that Thyssen donated about 650,000 Reichsmarks to various right-wing parties and groups, of which there were many, including the NSDAP, between 1923 and 1932. He was an adherent of the corporatist theories of Austrian philosopher Othmar Spann. In 1933 Thyssen was asked by the NSDAP to set up an Institute for Corporatism in Düsseldorf.[56] However, this was regarded as rivalling the Labor Front and was closed in 1936. In 1940, after having emigrated from Germany, Thyssen and his wife were captured in France and incarcerated in Germany for the duration of the war.

Prescott Bush

A figure that is associated with Thyssen is Prescott Bush. Because he was, like his sons Presidents George H. W. and George W. Bush, initiated into Lodge 322, vastly nonsensical theories has been woven around the Yale secret society, a.k.a. The Order of the Skull and Bones, as a pro-Nazi death cult, and the scions of influential families as part of an international Nazi conspiracy for world domination.

Prescott Bush was partner with W. Averell Harriman in Brown Brothers Harriman & Co., and the Union Banking Corporation. UBC acted as a clearinghouse for Thyssen interests. Because of this UBC’s assets were seized by the U.S government during the war. That Thyssen languished in Nazi concentration camps for the duration of the war is disregarded by those who seek a Wall Street connection with Hitler via Thyssen. Hence, The Guardian claimed to have new revelations in 2004 which turn out as nothing, with the focus on Thyssen being the businessman who “financed Hitler to power.” However, again more is said of the character of international capital than of big business backing for Hitler. The Guardian article states:[58]

“Erwin May, a treasury attaché and officer for the department of investigation in the APC,[57] was assigned to look into UBC’s business. The first fact to emerge was that Roland Harriman, Prescott Bush and the other directors didn’t actually own their shares in UBC but merely held them on behalf of Bank voor Handel. Strangely, no one seemed to know who owned the Rotterdam-based bank, including UBC’s president.

May wrote in his report of August 16 1941:

‘Union Banking Corporation, incorporated August 4 1924, is wholly owned by the Bank voor Handel en Scheepvaart NV of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. My investigation has produced no evidence as to the ownership of the Dutch bank. Mr. Cornelis [sic] Lievense, president of UBC, claims no knowledge as to the ownership of the Bank voor Handel but believes it possible that Baron Heinrich Thyssen, brother of Fritz Thyssen, may own a substantial interest.’

May cleared the bank of holding a golden nest egg for the Nazi leaders but went on to describe a network of companies spreading out from UBC across Europe, America and Canada, and how money from voor Handel traveled to these companies through UBC.

By September May had traced the origins of the non-American board members and found that Dutchman H. J. Kouwenhoven – who met with Harriman in 1924 to set up UBC – had several other jobs: in addition to being the managing director of voor Handel he was also the director of the August Thyssen bank in Berlin and a director of Fritz Thyssen’s Union Steel Works, the holding company that controlled Thyssen’s steel and coal mine empire in Germany.”

The connections are tenuous at best, but of the same character as the other supposed associations between transnational corporations and the Third Reich.

Who Paid the Nazi Party?

Like the assumption that Ford could have funded Hitler because they had similar views about Jews, Pool also makes the same assumption about Montagu Norman, Governor of the Bank of England, Schacht’s friend, because Norman was also antagonistic towards Jews (and the French). He deplored the economic chaos wrought on Germany by the Versailles diktat and the adverse impact that was having on world trade. On that score, he could have funded the Nazi party, but there is no evidence for it. Pool’s book is useful however insofar as he shows, despite himself, that the Nazi party was not a tool of big business.

I. G. Farben, for example, often depicted as one of the plutocratic wirepullers of the Nazi regime, and as the center of a Third Reich industrial death machine, was headed by liberals. Pool states that from its formation in 1925 I.G. Farben gave funding to all parties except the Nazis and the Communists. Not until 1932, with the NSDAP as the biggest party in parliament, did two representatives of the firm meet Hitler to get his views on the production of synthetic fuel.[59] Not surprisingly, Hitler was in favor, given that it was an important factor in an autarchic economy. However, the matter of funds for the party was not raised.

The upshot that we learn from Pool in regard to Nazi party funding is that, quoting economist Paul Drucker:[60]

“The really decisive backing came from sections of the lower middle classes, the farmers, and working class. […] As far as the Nazi Party is concerned there is good reason to believe that at least three-quarters of its funds, even after 1930, came from the weekly dues. […] And from the entrance fees to the mass meetings from which members of the upper classes were always conspicuously absent.”

Ludecke, despite his repudiation of Hitler, nonetheless cogently pointed out the difference in world-views between National Socialism and liberal capitalism. He wrote that the “newly legalized concept of property rights in Germany differs radically from the ideas of orthodox capitalism, though Marxian groups in particular persist in the erroneous contention that the Hitler system is a phase of the reaction designed to enforce the stabilization of capitalism.” He pointed out that “this planned economy signifies complete State control of production, agriculture, and commerce; of exports, imports, and foreign markets; of prices, foreign exchange, credit, rates of interest, profits, capital investments, and merchandizing of all kinds […].”[61] Ludecke quotes from an article in the Council of Foreign Relations journal Foreign Affairs (July 1937) that “the German conception of capitalism was always essentially different from the Anglo-Saxon, because it was developed under an entirely different conception of the state and government […].” Interestingly, the Foreign Affairs writer pointed out that what Hitler enacted was the consolidation of what had already been put in place by Social Democracy.[62] There were Social Democratic governments that had undertaken similar measures. Anyone familiar with New Zealand’s first Labor Government, assuming power about the same time as Hitler, could easily assume that what the Foreign Affairs writer is describing is the Labor Government’s economic policies.

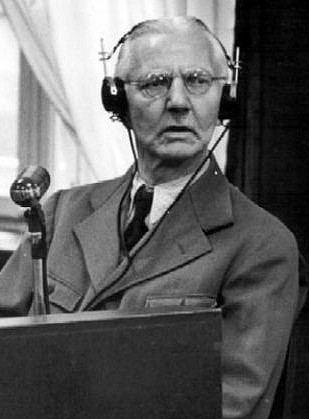

Hjalmar Schacht

A direct link between international capital and the Hitler regime was Hjalmar Schacht. He is instructive as to how the global banking nexus sought to co-opt the Nazi state, and how it failed. While researchers have focused on the first, they have neglected the implications of the latter. Sutton states that “Schacht was a member of the international financial elite that wields its power behind the scenes through the political apparatus of a nation. He is a key link between the Wall Street elite and Hitler’s inner circle.”[63] Schacht was a major figure in the creation of the Bank for International Settlements. The presence of German delegates to that institution during World War II is a primary element of this alleged Nazi-Wall Street nexus. One could say, and some do, the same about the International Committee of the Red Cross[64] and Interpol[65] during the war.

It is tempting to speculate as to whether Schacht was planted in the National Socialist regime to derail the more-strident aspects of the NSDAP ideology on international capitalism. It is unreasonable to claim that Hitler betrayed the National Socialist fight against international capital, because the full economic program of the NSDAP was not fulfilled. There is always going to be a difference in perspective as to what can be achieved when one is not in government. Schacht was obliged to work within National Socialist parameters and could not help but achieve some remarkable results. Like Montagu Norman and others, he was also concerned that the economic chaos in Germany engendered by the post-war Versailles diktat was having an adverse impact on world trade. Sutton does not mention that he ended up in a concentration camp because of his commitment to international capital. At least Higham states early in his book that “Hjalmar Schacht spent much of the war in Geneva and Basle pulling strings behind the scenes. However, Hitler correctly suspected him of intriguing for the overthrow of the present regime in favor of The Fraternity[66] and imprisoned him late in the war.”[67]

Date: 21 July 1947, Provenance: From Public Relations Photo Section, Office Chief of Counsel for War Crimes, Nuernberg, Germany, APO 696-A, US Army. Photo No. OMT-V-W-16. [Public Domain] via Wikimedia Commons

“National Socialist agitators led by Gottfried Feder had carried on a vicious campaign against private banking and against our entire currency system. Nationalization of banks, abolition of bondage to interest payments and introduction of state Giro ‘Feder’ money, those were the high-sounding phrases of a pressure group which aimed at the overthrow of our money and banking system. To keep this nonsense in check, [I] called a bankers’ council, which made suggestions for tighter supervision and control over the banks. These suggestions were codified in the law of 1934 […] by increasing the powers of the bank supervisory authority. In the course of several discussions, I succeeded in dissuading Hitler from putting into practice the most foolish and dangerous of the ideas on banking and currency harbored by his party colleagues.”

What Schacht did introduce was the MEFO bill. Between 1934 and 1938 12,000,000 bills had been issued at 3,000,000 bills per year. MEFO bills were used specifically to facilitate the exchange of goods.[69] However, once full employment had been achieved, Schacht wanted to return to orthodox finance. Hitler objected, and it was agreed that Schacht would continue as president of the Reichsbank until 1939, on the assurance that the MEFO issue would be halted when 12,000,000 bills had been reached.[70] After the war Schacht assured readers that fiat money such as the MEFO,[71] like barter, should not become the norm for the world, despite their successes in Germany.

Likewise, Schacht opposed the autarchic aims of National Socialism. Schacht was, in short, ideologically inimical to the raison d’etre of National Socialism. Today he would be a zealous exponent of globalization along with David Rockefeller and George Soros. He wrote after the war:[72]

“Exaggerated autarchy is the greatest obstacle to a world-wide culture. It is only culture which can bring people closer to one another, and world trade is the most powerful carrier of culture. For this reason I was unable to support those who advocated the autarchistic seclusion of a hermitage as a solution to Germany’s problems.”

Yet Schacht was also responsible during six years for re-establishing Germany’s economy, and among the achievements which were in accord with National Socialism was the creation of bi-lateral trade agreements based on reciprocal credits. Schacht wrote of this:[73]

“In September 1934 I introduced a new foreign trade programme which made use of offset accounts, and book entry credit. […]

My plan was to some extent a reversion to the primitive barter economy, only the technique was modern. The equivalent value of imported goods was credited to the foreign supplier in a German banking account, and vice versa foreign buyers of German goods could make payment by means of these accounts. No movement of money in marks or foreign currency took place. All was done through credits and debits in a bank account. Thus no foreign exchange problem came into being.”

Schacht then hints at what would result in a clash of systems, and world war:[75]

“Those interested in the exchange of goods came into conflict with those interested solely in money. There was soon a battle royal between the exporters who sold goods to Germany, and the creditors who wanted their interest. Both parties demanded to be given preference, but the decision always went in favor of foreign trade.

I concluded special agreements with a number of states which were our principal sources of raw materials and foodstuffs. Anyone who wished to sell raw materials to Germany had to purchase German industrial products. Germany could pay for goods from abroad only by means of home-produced goods, and was thus able to trade only with countries prepared to participate in this bilateral programme. There were many such countries. The whole of South America, and the Balkans were glad to avail themselves of the idea, since it favoured their raw materials production. By the spring of 1938 there were no less than 25 such offset account agreements with foreign countries, so that more than one half of Germany’s foreign trade was conducted by means of this system. This trade agreement system in which two countries – Germany and one foreign country – were always involved, has entered economic history under the name of ‘bilateral’ trading policy. [74]

It created much ill-feeling in countries which were not part of the system. These were precisely those countries who were Germany’s main competitors in world markets, and who had hitherto attempted to effect repayment of their loans by imposing special charges on their imports from Germany. The countries participating in bilateral trade were not amongst those which had granted Germany loans. They were primary producers or predominantly agrarian, and had hitherto scarcely been touched by industrialisation. They utilised the bilateral trading system to accelerate their own industrial development by means of machines and factory installations imported from Germany.”

However, Schacht was not even in favor of the permanence of this great alternative method of world trade that allowed for the peaceful development of backward economies. Imagine the difference to the world today had this system been allowed to live and grow. Schacht remained a member of The Fraternity, to use Higham’s term, and he worried that

“The bilateral trading system kept the German balance of payments under control for many years, but it was not a satisfactory solution, nor was it a permanent one. It is true that it enabled Germany to preserve its industry and to feed its populace, but the system could not provide a surplus of foreign exchange. No more was ever imported than was exported. Import and export balanced out exactly in monetary terms. Thus this system achieved the very opposite of what I, in agreement with the foreign creditors, had deemed to be necessary.”[76]

As if to emphasize that he had never intended to renege on his loyalty to The Fraternity, Schacht lamented apologetically:[77]

“Already at the time when I introduced the bilateral trading system I made it known that I regarded it as a most inadequate and unpleasant system, and expressed the hope that it would soon be replaced by an all-round, free, multilateral trading policy. In fact the system did have some considerable influence on the trading policies of Germany’s competitors.”

It seems that Schacht had unleashed forces of economic justice and equity upon the world in spite of his intentions and it could only be stopped by war. Again: “For my part I would not say that the bilateral trading system, ranks among those of my measures which are worth copying.”[78] Introducing barter in world trade seems to have been the source of great shame to Schacht.

Schacht criticizes Hitler for having financed the war neither with taxation nor with the raising of loans. “Instead he chose to print banknotes,”[79] which of course is anathema to a banker such as Schacht, claiming the looming prospect of “inflation.” True enough, the “inflation” did not occur because of the other state controls, but Schacht stated that it did happen – in 1945.[80] At the end of the war the bills in circulation amounted to between 40 and 60 billion marks. Schacht comments that it did not result in hyperinflation, and that the aim was to keep the level at that amount.[81] Might one conclude then that the fiat money that had been issued by the Third Reich had not been the cause of inflation, but rather the destruction of German production by the end of the war? At any rate it was not until 1948 that the Allied occupation attempted currency reform, based on the recommendations of U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., by a massive devaluation of the mark. This is what had devastating consequences upon middle- and working-class Germans, and Schacht states that “malevolent intent was involved.”[82] Fiat money has long been the great bugaboo among orthodox economists. Amusingly, Schacht spent two days during the Nuremberg proceedings trying to explain the MEFO bills, and when asked for a third time, gave up and refused.[83]

The Bank for International Settlements reports show that up to the end of the war the Reich Government used a variety of methods of finance, including what Schacht had ridiculed as “state Giro ‘Feder’ money.”

Another interesting point made by Schacht is that, contrary to the widespread assumption, German economic recovery was not based on war expenditure. Schacht even criticizes Hitler with the assumption that he did not understand the requirements of war preparation. During 1935-1938 armaments expenditure was 21 billion RM.[84] Schacht assumes that this was due to Hitler’s ignorance. The other alternative is that there was no long-term plan to wage a major war or prolonged aggression. There was no buildup of raw materials and no real war economy until 1939.

In 1939 Schacht was replaced by Dr. Walther Funk, who had served in 1932 as deputy chairman of the NSDAP’s economic council under the chairmanship of Feder. The replacement of Schacht by Funk working under the direction of Göring the head of the Four Year Plan, seems to be an indication that a transitional phase had been completed and that the Government was well aware of Schacht’s role as an agent for international capital. Otto D. Tolischus, writing from Berlin for The New York Times, commented:[85]

“Dr. Schacht was ousted because he believed that Germany had reached the limit in debt-making and currency-expansion, that any further expansion spelled danger to the economic system, for which he still considered himself responsible, and that the government would have to curtail its ambitions and confine itself to the nation’s means. […]

No authoritative explanation of the new financial policy is available so far, but judging from hints in the highest quarters, the policy is likely to proceed about as follows:

- Expand the currency circulation only for current exchange demands and not for special purposes.

- Open the capital market for private industry and make private industry finance many tasks hitherto financed by the state, either directly or by prices on public orders, which have enabled industry to finance the expansion of new Four-Year Plan factories out of accumulated profits and reserves.

- Create a non-interest bearing credit instrument with which the state, now having to share the capital market with private enterprise, will finance its own further orders in anticipation of increasing tax receipts from the resulting expansion of production.

In one respect therefore, Herr Funk presumably will continue ‘pre-financing’ the state’s orders as did Dr. Schacht, but whereas Dr. Schacht did it with bills, loans, delivery certificates and other credit instruments, all of which cost between 4½ and 5 per cent interest per year, Herr Funk proposes doing it with non-interest-eating instruments.

How that is to be done is his secret, but the mere mention of interest-free credit instruments inevitably recalls the plan of Gottfried Feder which at one time fascinated Chancellor Hitler, but which Dr Schacht vetoed.”

What had taken place was an ultimatum from the Reichsbank, which in January 1939 refused to grant the state any further credits.[86] This amounted to a mutiny by orthodox banking. On January 19 Schacht was removed a president of the Reichsbank, and his position was assumed by Economics Minister Funk. Hitler issued as edict that obliged the Reichsbank to provide credit to the state.

Funk commented on Germanys’ monetary policy a year later:[87]

“Turning from the external to the internal sector, the question, ‘How is this war being financed in Germany?’ is one in which the world shows a lively interest. The war is financed by work, for we are spending no money which has not been earned by our work. Bills based on labour – drawn by the Reich and discounted by the Reichsbank – are the basis of money […].”

Broadly, it seems that Feder’s ideas were being implemented. The NSDAP broke the bondage of the international gold merchants, and this was being openly discussed as the way of the future. Germany created an autarchic trading bloc both before and during the war, based on barter through a Reich clearing center. Pegging national currencies to the Reichsmark resulted in immediate wage increases in the occupied states. The Bank for International Settlements Annual Report for 1940-1941 quoted finance spokesmen from Fascist Italy and the Third Reich:

“The development of clearings in Europe has given rise to certain fears with regard to the future position of gold as an element in the monetary structure. It has since been noted that Germany has been able to finance rearmament and war with very slight gold reserves and that the foreign trade of Germany and Italy has been carried on largely on a clearing basis. Hence the question is being asked whether a new monetary system is being developed which will altogether dispense with the services of gold.

In authoritative statements made on this subject in Germany and Italy a distinction is drawn between different functions of gold. The president of the German Reichsbank said in a speech on 26 July 1940 that ‘in any case in the future gold will play no role as a basis of European currencies, for a currency is not dependent upon its cover but on the value which is given to it by the state, i.e. by the economic order as regulated by the state.’ ‘It is,’ he added, ‘another matter whether gold should be regarded as a suitable medium for the settlement of debit balances between countries, but we shall never pursue a monetary policy which makes us in any way dependent upon gold, for it is impossible to tie oneself to a medium the value of which one cannot determine oneself.'”[88]

After the war Schacht, while acquitted of charges at Nuremberg, did not escape the vindictiveness of the Allies, despite the testimonials of those who stated that he was from the start an enemy of Hitler. In 1959 Donald R. Heath, American ambassador to Saudi Arabia, who had been director of political affairs for the American military government during the time of the Nuremberg trials, wrote to Schacht telling him that he had tried to intervene for Schacht with U.S. prosecutor Robert Jackson:[89]

“After consultation with Robert Murphy, now Under Secretary of State, and with the permission of General Clay, I went to Nürnberg to see Jackson. I told Jackson not only should you never have been brought before that tribunal but that you had consistently been working for the downfall of the Nazi regime. I told him that I had been in touch with you consistently during the first part of the war and Under Secretary of State Wells through me, and that you had passed on to me information adverse to the Nazi cause […].”

In 1952 Schacht applied to establish a bank in Hamburg but was refused on the basis that the MEFO bills had offended banking morality. Notably, it was the Socialists who found the MEFO objectionable. [90]

Who Wanted War?

If some industrialists and businessmen such as Henry Ford Sr. did not want war and supported the America First Committee, others, including those supposedly pro-Nazi, were clamoring for aid to Britain and antagonism towards Germany well before Pearl Harbor. Senator Rush D. Holt, a liberal pacifist, during the last session of the 76th Congress, exposed the oligarchs promoting belligerence against Germany. Commenting on an influential committee, Defend America by Aiding the Allies, headed by newspaperman William Allen White, to agitate for war against Germany, or at least “all aid short of war” to Britain, Senator Holt said the founders included “eighteen prominent bankers.” Among those present at its April 1940 founding were Henry L. Stimson, who had served as counsel for J. P. Morgan and senior Morgan partner Thomas W. Lamont.[91] The campaign began on June 10, 1940, with advertisements entitled “Stop Hitler Now” appearing in newspapers throughout the USA. There was an allusion to the advertisements being paid for by “a number of patriotic American citizens.” On July 11, Senator Holt spoke to the Senate on the advertisement:[92]

“You find it is not the little fellows who paid for this advertisement, ‘Stop Hitler Now!’ […] Listen to these banks. The directors of these banks, or the families of directors, paid for this advertisement. Who are they? No wonder they want Hitler stopped. Director of J. Pierpont Morgan & Co.; Director of Drexel & Co.; Director of Kuhn, Loeb Co., – Senators have heard that name before – Kuhn, Loeb & Co. international banking. No wonder Kuhn, Loeb & Co. helped finance such an advertisement. A Director of Lehman Bros., another international banking firm, helped pay for this ‘Stop Hitler’ advisement, and a number of others.”

Holt, referring to a list of names of the advertisement sponsors, stated that they are not the types who die in battle, or the fathers of those who die in battle. He named the wives of international financiers W. Averell Harriman,[93] H. P. Davison,[94] the late Daniel Guggenheim,[95] and John Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb & Co. Other sponsors included Frederick M. Warburg,[96] a partner of Kuhn, Loeb & Co.; Cornelius V. Whitney, mining magnate associated with Rockefeller and Morgan interests; and Thomas W. Lamont of J. P. Morgan Co. In communications, there was Henry Luce, publisher of Time, and Samuel Goldman, the Hollywood mogul. Holt described these sponsors not as “patriots,” but as “paytriots.”

In his farewell speech to the Senate, Holt nailed exactly what was behind the agitation for war against Germany, and the different attitude towards the USSR:

“Germany is a factor in world trade against England, Russia is not.. […] American boys are going to be sent once again to Europe, in the next session of Congress, not to destroy dictatorship or to preserve democracy but to preserve the balance of power and protect world trade.”

It is interesting to read now that in reply Senator Josh Lee reminded Holt that Roosevelt had promised that “no American expeditionary force would be sent to Europe.” Holt replied that Roosevelt had broken many promises.[97]

A survey of the newspaper headlines also indicates those most avid in calling for U.S. war against Germany, from as early as 1938; and indeed the war hysteria that was being pushed against Germany from an early date. Apart from President Franklin D. Roosevelt promising that he would not involve the USA in another European war, out of one side one his mouth while out of the other demanding an urgent military buildup, the two individuals who stand out most prominently in war-mongering are presidential confidant and Wall Street financier Bernard M. Baruch and New York Governor Herbert H. Lehman of Lehman Brothers. In October 1938 Baruch and Roosevelt were both calling for increased military spending by the USA. In January 1939 Baruch offered $3,300,000 of his own fortune to help equip the U.S. army. In February 1939 Roosevelt was saying that U.S. involvement in helping Britain and France was “inevitable,” although hostilities were not declared until September. In May 1940, amidst war-mongering by “rabbis” and Roosevelt, “Baruch exhorts U.S. to re-arm.” In June “Lehman tells Roosevelt to send all arms asked.” A few days later James P. Warburg, of the famous banking dynasty, “says only force will stop Hitler.” In July Lehman called for compulsory military service. In January 1941 James P. Warburg “asks for speed” in rearming the USA. A few days previously Rabbi Stephen S. Wise urged “all aid short of war” to Britain, as Roosevelt asked “billions in loans to fight Axis,” and Lehman “urges speedy passage of aid measure.” In February “Jewish Institute to Plan Role in New World Order,” and “Lehman Urges Speed in Voting British Aid Bill.”[98] Lehman, U.S. diplomat Bullitt, and others of the pro-war party were pitching to the American public, overwhelmingly opposed to war, that if Britain is defeated, the USA faced impending invasion.[99] Those such as Colonel Charles Lindbergh, who showed that such alarmist claims were utter nonsense, were pilloried as “pro-Nazi.”

Conclusion

Some Wall Street luminaries who are supposed to have been “pro-Nazi” on the basis of business affiliations in Germany were among those agitating for war against Germany. Foreign business holdings were held in trust throughout the war by Germany in accordance with international law. The one individual who had convincing links with international capital, Hjalmar Schacht, was relieved of all positions by 1939 and ended up in a concentration camp. Those German businessmen who did provide funds to the Nazi party did so at a comparatively late date, and were of nationalistic sentiments in a German tradition that was alien to that of the self-interest of the English free-trade school. Even those foreign businessmen who might reasonably have been expected to fund the NSDAP on ideological grounds, primarily Henry Ford, did not do so, persistent allegations to the contrary.

The Third Reich was a command economy, and corporate executives became “trustees” of their firms, subject to state supervision. The NSDAP premise: “the common interest before self-interest” was upheld throughout the regime. Dividends and profits were limited to a large extent. While it is a widespread assumption that Hitler reneged on the “socialist” principles of the NSDAP program, what the regime did carry out was extensive in terms of bilateral trade, and the use of unorthodox methods of finance. The machinations of international capital, including those who were supposedly pro-German, were for war, especially if Germany could not be persuaded to return to orthodox methods of trade and finance. War came the same year as Schacht was dismissed from office.

Notes:

| [1] | See for example: “Fascism” in ABC of Political Terms (Moscow: Novosti Press Agency Publishing House, 1982), pp. 29-30; cited in Roger Griffin, Fascism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), pp. 282-283. |

| [2] | Ibid. |

| [3] | Roger Eatwell, Fascism: A History (London: Vintage, 1995). |

| [4] | Zeev Sternhell, The Birth of Fascist Ideology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1980); Neither Left nor Right: Fascist Ideology in France (Princeton, 1986). |

| [5] | “Guidelines of the German Workers’ Party,” January 5, 1919, in Barbara M. Lane and Leila J. Rupp, Nazi Ideology Before 1933(Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1978), pp. 9-11. |

| [6] | Oswald Spengler [1926], The Decline of the West (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1971), Vol. 2, p. 402. |

| [7] | Hitler, Mein Kampf (London; Hurst and Blackett, 1939), pp. 180-181. |

| [8] | Ibid., p. 183. |

| [9] | Ibid. |

| [10] | Friedrich List, The National System of Political Economy (1841) online at: http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/315 |

| [11] | Ibid., “Author’s Preface.” |

| [12] | Antony Sutton, Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution (New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House Publishers, 1974). |

| [13] | Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler (Suffolk: Broomfield Books, 1976). |

| [14] | Everette O. Lemons, A Revolution in Ideological Inhumanity (Lulu Press, 2013), Vol. 1 pp. 339-340. |

| [15] | Ibid. , p. 389. |

| [16] | Kurt G. W. Ludecke, I Knew Hitler (London: Jarrolds Publishers, 1938), pp. 287-288. |

| [17] | Sutton, How The Order Creates War and Revolution (Bullsbrook, W. Australia: Veritas Publishing (1985). Sutton’s evidence for Wall Street funding of Hitler comprises nothing other than the supposed links with Fritz Thyssen (pp. 58-63), which will be considered below. |

| [18] | “Berlin hears Ford is backing Hitler,” New York Times, December 20, 1922, cited by Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, pp. 90-92. |

| [19] | See for example: “ The Constantine Report,” http://www.constantinereport.com/new-york-times-dec-20-1922-berlin-hears-ford-backing-hitler/ Also the citing of the article in a university thesis: Daniel Walsh, “The Silent Partner: how the Ford Motor Company Became an Arsenal of Nazism,” p. 4, University of Pennsylvania, http://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=hist_honors |

| [20] | Antony Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler (Suffolk: Broomfield Books, 1976), p. 92. |

| [21] | Ibid. |

| [22] | Scott Nehmer, Ford, General Motors and the Nazis: Marxist Myths About Production, Patriotism and Philosophies (Bloomington, Indiana: Author House LLC, 2013). |

| [23] | Professor Eric Johnson seems to be particularly close to Jewish interests, which might explain his outrage at Mr. Nehmer’s lack of subservience. See: Central Michigan University, History Department Newsletter, “Faculty Publications and Activities,” June 2010, p. 2, https://www.cmich.edu/colleges/chsbs/history/about/documents/historynewsletter2010.pdf |

| [24] | Scott Nehmer, “Ford General Motors, and the Nazis,” http://scottnehmer.weebly.com/ |

| [25] | Antony Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, pp. 104-105. Trading with the Enemy (London: Robert Hale, 1983), by Charles Higham, is along the same lines. |

| [26] | Kurt G. W. Ludecke, I Knew Hitler (London: Jarrolds Publishers, 1938). |

| [27] | Ibid., p. 196. |

| [28] | Ibid., p. 203. |

| [29] | Ibid., p. 201. |

| [30] | Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, p. 92. |

| [31] | James Pool, Who Financed Hitler (New York: Pocket Books, 1997), pp. 65-96. |

| [32] | New York Times, June 4, 1938; quoted by Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, pp. 90-91. |

| [33] | Ibid., p. 90. |

| [34] | Pool, p. 84. |

| [35] | George T. Eggleston, Roosevelt, Churchill and the World War II Opposition (Old Greenwich, Conn.: The Devin-Adair Co., 10979), pp. 96-97. |

| [36] | Ibid., pp. 101, 146, 147, 164, 165. |

| [37] | Ibid., p. 101. |

| [38] | Thomas Lamont, “American Business in War and Peace: Economic Peace Essential to Political Peace,” speech before the Academy of Political Sciences, November 15, 1939, quoted by Peter Luddington, Why the Good War was Good: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New World Order, doctoral thesis, UCLA (Ann Arbor: ProQuest LLC, 2008), pp. 112-113. |

| [39] | K. R. Bolton, “The Geopolitics of White Dispossession” in Radix, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2012, pp. 108-110. |

| [40] | Ibid., pp. 112-114. |

| [41] | Elliott Roosevelt, As He Saw It (New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1946), p. 35. |

| [42] | Charles Higham, Trading with the Enemy: How the Allied Multinationals supplied Nazi Germany throughout World War Two (London: Robert Hale, 1983)., pp. 166-177. |

| [43] | Edwin Black, “Hitler’s Car Maker: The Inside Story of How General Motors Helped Mobilize the Third Reich,” History News Network, http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/37935 |

| [44] | James D. Mooney, Always the Unexpected, unpublished autobiography, ed. Louis P. Lochner, (State Historical Society of Wisconsin, Madison, 1948), p. 24; cited by David Hayward, Automotive History, “Mr. James D. Mooney: A Man of Missions,” http://www.gmhistory.chevytalk.org/James_D_Mooney_by_David_Hayward.html |

| [45] | Mooney, ibid., p. 27. |

| [46] | Luddington, p. 113. |

| [47] | Dr. Greg Bradsher, “German Administration of American Companies 1940-1945: A Very Brief Review,” U.S. National Archives, June 6, 2001, http://www.archives.gov/research/holocaust/articles-and-papers/german-administration-of-american-companies.html |

| [48] | Ibid. |

| [49] | Rinehold Billstein, et al Working for the Enemy: Ford, General Motors and Forced Labor in Germany During the Second World War (Berghahn Books, 2004), p. 141. |

| [50] | Anita Kugler, Working for the Enemy, ibid., p. 36. |

| [51] | Richard Overy, The Dictators (London: Allen Lane, 2004), p.p. 438-439. |

| [52] | Antony Sutton, How The Order Creates War and Revolution, pp. 3-9. |

| [53] | Ibid., inter alia. |

| [54] | Frtiz Thyssen, I Paid Hitler (New York: Farrar & Rinehart Inc., n.d.) p. 88, cited by Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, p. 25. |

| [55] | Sutton, ibid., p. 25. |

| [56] | “Fritz Thyssen,” ThyssenKrupp, http://www.thyssenkrupp.com/en/konzern/geschichte_grfam_t2.html |

| [57] | Alien Property Commission. |

| [58] | “How Bush’s Grandfather Helped Hitler’s Rise to Power,” The Guardian, September 25, 2004, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2004/sep/25/usa.secondworldwar |

| [59] | Pool, pp. 336-337. |

| [60] | Paul Drucker, The End of Economic Man (London: 1939), p. 105; quoted by Pool, p. 272. |

| [61] | Ludecke, p. 692. |

| [62] | Ibid., p. 693. |

| [63] | Sutton, Wall Street and the Rise of Hitler, p. 18. |

| [64] | Arthur Spiegelman, “WWII Documents Bolster Nazi-Red Cross Connection,” Detroit Free Press, August 30, 1996, p. 6A. |

| [65] | Gerald L. Posner, “Interpol’s Nazi Affiliations Continued after War,” New York Times, March 6, 1990, http://www.nytimes.com/1990/03/06/opinion/l-interpol-s-nazi-affiliations-continued-after-war-137690.html |

| [66] | Higham’s term for the international financial cabal. |

| [67] | Higham, pp. 9-10. |

| [68] | Hjalmar Schacht, The Magic of Money (London: Oldbourne, 1967), p. 49; http://www.autentopia.se/blogg/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/schacht_the_magic_of_money.pdf |

| [69] | Ibid., p. 117. |

| [70] | Ibid., p. 114. |

| [71] | Ibid., p. 116. |

| [72] | Ibid., p. 85. |

| [73] | Ibid., pp. 85-86. |

| [74] | Ibid., p. 86. |

| [75] | Ibid., p. 87. |

| [76] | Ibid., p. 87. |

| [77] | Ibid., p. 87. |

| [78] | Ibid., p. 89. |

| [79] | Ibid., p. 98. |

| [80] | Ibid., p. 143. |

| [81] | Ibid., p. 109. |

| [82] | Ibid., p. 121. |

| [83] | Ibid., p. 118. |

| [84] | Ibid., p. 101. |

| [85] | “The Abolition of Debt-Bonds Is the Story behind the Removal of Dr. Schacht,” Social Justice, February 13, 1939, p. 11 |

| [86] | Schacht, p. 117. |

| [87] | Walther Funk, “The Economic Re-Organisation of Europe,” Speech: July 25, 1940. |

| [88] | The Bank for International Settlements Annual Report for 1940-1941, Eleventh Annual Report, June 9, 1941, p. 96. |

| [89] | Hjalmar Schacht, p. 107. |

| [90] | Ibid., p. 118. |

| [91] | “Rabid Tory Propagandists are Worst War Profiteers,” Weekly Roll-Call, January 25, 1941, p. 6; citing Chicago Daily Tribune, June 12, 1940. |

| [92] | “Aid to Britain Screech comes from Wall Street Profiteers facing loss,” Weekly Roll-Call, February 3, 1941, p. 5. |

| [93] | An elder statesman of American diplomacy under several presidents, he was a founder of Brown Brothers Harriman international bank, one of whose partners was fellow Lodge 322 initiate Prescott Bush. On account of business affiliations with German corporations such as those of Fritz Thyssen, Harriman is assumed to have been a Wall Street backer of Hitler, along with Prescott Bush. His sponsorship of war agitation shows this is not the case. |

| [94] | Associated with J.P Morgan interests, he was a Lodge 322 initiate in 1920. |

| [95] | Guggenheim, the copper magnate, had been a member of the National Security League, headed by J. P. Morgan, which had agitated for war against Germany during World War I. |

| [96] | A director in Harriman railway interests. |

| [97] | “Senator Holt in Farewell Speech calls Pro-War agitators ‘Traitors’,” Weekly Roll-Call, January 11, 1941, p. 9. |

| [98] | “The Chronology of the Devil who wants War,” Weekly Roll-Call, February 17, 1941, p. 2. |

| [99] | “Prompt passage of aid bill urged,” The Pittsburgh Press, January 26, 1941, pp. 1, 12. “U.S. envoys who saw Nazis in action fear invasion, back Lend-Lease Bill,” Pittsburgh Press, p. 12. |

Bibliographic information about this document: Inconvenient History, 2015, vol. 7, no. 3

Other contributors to this document: n/a

Editor’s comments: n/a