The Russians in Berlin in 1945

A Review

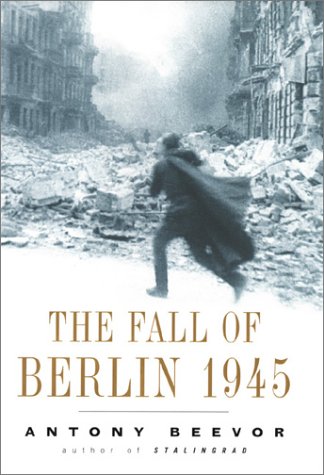

Antony Beevor, The Fall of Berlin 1945, Viking Penguin, London/New York, May 2002, 512 pp. hardcover, $29.95

With much hullabaloo, the publication of the newest book of the British military historian Anthony Beevor was announced at the beginning of April: For example, “Rapists of the Red Army Exposed” was the headline by Chris Summers of the British government broadcasting company on BBC News Online. Two million German women were raped during the advance of the Red Army into Germany toward the end of the Second World War, many of them several times. In Berlin alone, 130,000 women were raped, of whom 1,000 subsequently committed suicide. To the German public, this is hardly new information, nor would it have rated sensational headlines in the media there.

Beevor’s book describes the advance of the Red Army into East Germany and the Battle for Berlin primarily from a military viewpoint; thus the cruel swath of looting, extortion, mass murder, forced expulsions and rape is not Beevor’s central focus of interest. Nonetheless, he was shocked by what was turned up in the course of his investigation. Inevitably, anyone familiar with the history of that time asks himself what the state of competency of a military historian of the Second World War must be, to whom the events in East and Central Germany at the end of 1944 and beginning of 1945 were not known by the year 2000.

The high point of the book, however, is that Beevor considers it to be understandable and excusable what happened in Germany at the end of the war. First of all, he takes the view that any man in the extremities of wartime conditions would be susceptible to the temptation to loot and rape. Second, his view is that by the end of the war, the Germans had indeed only reaped what they had sown in 3½ years in Russia, which was the reason that the Soviet military leadership averted its eyes at what was taking place in Germany.

Beevor, therefore, has been taken in by the old Stalinist-“anti-fascist” war lies that German soldiers in Russia had murdered, looted, extorted and raped at will. But as a military historian who claims to know the subject about which he is writing, Beevor must know that in no sense was this true. Through all the horror of the Eastern campaign, the German soldiers even conducted themselves, all in all, in an extraordinarily civilized manner, if one compares them to all other armies of World History. One might take for comparison, for instance, the contribution of Walter Post, Die Wehrmacht im Zweiten Weltkrieg (The Wehrmacht in the Second World War), in the anthology edited by Joachim Weber, Armee im Kreuzfeuer (Army in the Crossfire, Universitas, Munich 1997).

Yet even this degree of eager servility to the prevailing Political Correctness still wasn’t enough for the current Russian Ambassador in England, Grigory Karasin. The Ambassador maintains, in a letter to the Editor of the Daily Telegraph, that Beevor’s statements concerning the horrendous rampages of the Soviet soldiers in Germany are nothing but “lies and allegations” and that moreover, they have been “disproved” by a Russian historian:

“It is a shame to have to deal at all with this clear case of an insult to my people, who have freed the world from Nazism.”

Yes indeed, let’s be grateful to the Devil, who has driven the rascal away!

On the other hand, Beevor presents interesting findings that the Soviets not only raped German women, to be sure, during their advance into Germany, but later as well, when hundreds of thousands of women were carried off as slaves and were constantly further abused in imprisonment, many of them in Soviet Army brothels. It also emerges from the Soviet documents examined by Beevor that many of the “repatriated” Russian and Ukrainian women who collaborated with the Germans during German occupation shared the fate of their German sisters in suffering. According to Beevor, the women were commonly degraded by becoming the war booty of Soviet soldiers.

In taking his position vis-a-vis the BBC, Professor Oleg Rzheshevsky, Director of the Department of Military History at the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, maintained that Beevor’s charges were not supported by documents – although he had to admit that he had not read Beevor’s book nor examined the sources – and that they were merely based upon the non-credible testimony of German women. Actually, he claimed, the majority of the Soviet soldiers had behaved with good will toward the German population.

The only question is how, despite 55 years of unrelenting propaganda from the peace-loving Soviet Union and the total suppression of critical historiography in Central Germany, its populace can nevertheless still recall the Soviet atrocities so clearly and with such unanimity. Here, a collective memory exists contrary to and despite the propaganda, not, as in the Holocaust, where a collective memory was created parallel to the propaganda and by it. Rzheshevsky’s thesis of the non-credibility of hundreds of thousands of German witnesses is, therefore, ridiculous.

Professor Richard Overy, Historian at King’s College in London, believes the Russians have suppressed this episode of their history because they take the view that the retribution which fell upon Germany was only just, in light of the much worse German crimes in Russia. I will spare myself making any comment in response to this.

If one compares this book with the book authored by Joachim Hoffmann Stalin’s War of Extermination, 1939-1945 (Theses and Dissertations Press, Capshaw, AL, 2002, available for $40.00 from Castle Hill Publishers), Beevor’s book has but one advantage, which is that the Soviet swath of blood through Eastern Europe has been documented even better. Beevor, however, has not dealt with the context of this conflict and thus the causes of the outrages by Soviet soldiers at the end of the war. That is also the reason why the book is discussed in the media abroad in the first place and consequently will be a success: It does not contradict the image of the poor, invaded, raped, plundered, peace-loving Soviet Union, which saved the world from ‘Nazism’. In this regard, Hoffmann’s book is, of course, significantly better documented and its argumentation is accordingly more refined. For this reason, the English edition of this book has been given the silent treatment by all English-language media.

Bibliographic information about this document: The Revisionist 1(1) (2003), pp. 98f.

Other contributors to this document:

Editor’s comments: First published in German in "Vierteljahreshefte für freie Geschichtsforschung," 6(2) (2002), pp. 223f.