Incontrovertible Facts on Cremations in National-Socialist “Extermination Camps”

Foreword

Orthodox Holocaust historiography pompously calls itself “scientific,” but this term is purely formal and empty, as it refers to the method it claims to use, which is in fact fallacious, because it aims to obtain the predetermined result through the selective use of sources habitually misrepresented, whether out of ignorance or deliberate intention.

This historiography is, moreover, seriously deficient, because it completely lacks (despite Jean-Claude Pressac’s inane attempts) a serious technical and technological analysis of the events and facilities that form the backbone of the orthodox Holocaust narrative. I refer, of course, first and foremost to the story of the homicidal gas chambers, a subject that has been masterfully and rigorously examined in the fullest scientific sense (i.e., in physical, chemical, toxicological, technical, and architectural aspects) by Germar Rudolf.[1] However, I also refer to the cremation of the alleged victims. Scientific treatment of this aspect should have been inescapable, because one cannot seriously claim that hundreds of thousands of bodies were cremated, most under prohibitive atmospheric conditions (the claimed mass burnings outdoors) without even asking how this was done and whether it was materially possible. Instead, orthodox historians assumed, from the very beginnings of revisionism, a dogmatic and arrogant attitude which found full expression in the famous appeal of 34 French historians published on February 21, 1979:[2]

“There is no need to ask how such a mass murder was technically possible. It was technically possible because it happened. This is the obligatory starting point for any historical inquiry into this subject. It behooves us simply to reiterate this truth: there is not, nor can there be, any debate about the existence of the gas chambers.”

This appeal was essentially directed against Robert Faurisson, who had given the Italian periodical Storia Illustrata a seminal interview a few months earlier. In this interview, Faurisson published the first ever technical approach to the “gas chambers” problem.[3] However, this approach applied in principle to the question of cremation as well, although historians at the time did not even consider the problem.

And in fact, no Holocaust historian (apart from Jean-Claude Pressac with his feeble attempts) ever seriously considered the cremation issue; indeed, no one ever perceived it as a problem, because everyone, starting with the historians at the Auschwitz Museum, took the thermotechnical delusions of “eyewitnesses” at face value. The first and only scientific study of the crematoria at Auschwitz and all other German concentration camps still remains the one which I compiled with the collaboration of engineer Dr. Franco Deana, titled The Cremation Furnaces of Auschwitz. A Technical and Historical Study,[4] which radically debunks the crematoria myths of orthodox Holocaust historiography.

In an expert report prepared for the defense team of Deborah Lipstadt and the English publishing company Penguin Books Ltd[5] – in the course of the defamation lawsuit brought against them by David Irving, which took place from January 11 to April 11, 2000 before the Royal Court of Justice in London – and in an edited and expanded version of this expert report published as a book under the title The Case for Auschwitz. Evidence from the Irving Trial,[6] Dutch cultural historian Robert Jan van Pelt expounded “technical” considerations about cremation that are pathetic subterfuges to justify the delusional claims of “eyewitnesses” (in particular, of Henryk Tauber[7]). I documented this extensively in a study appropriately titled Robert Jan van Pelt’s Deluded Ramblings about Crematoria at Auschwitz-Birkenau.[8]

For the so-called extermination camps of Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka (the “Aktion Reinhardt” camps), which are said to have resulted in more than 1.5 million gassing victims, the situation of orthodox Holocaust historiography is even more precarious. Here, too, orthodox historians have relied on absurd witness statements, and reconstructed a purely imaginary picture of events.

A book by Andrej Angrick, whose title translates to “Operation 1005”: Trace Removal of Nazi Mass Crimes 1942-1945,[9] is a typical example of pseudo-scientific literature in the sense mentioned earlier. It is based on an immense, presumably critically reviewed body of anecdotal and trial sources that have no connection with factual and technical reality.

In my study on the same topic – Part two of my two-volume study on the Einsatzgruppen[10] – I instead prioritized this fundamental aspect by reporting and evaluating sources on a historical-technical basis.

Absurdly, the vacuum left by orthodox historians has been filled – in a way described in Subchapter II.2 – by a quack blogger, Roberto Muehlenkamp, who deserves credit at least for recognizing the essential importance of this issue.

I. Cremations in the Topf Cremation Furnaces (Auschwitz-Birkenau)

1) The Coke Consumption of the Topf Crematorium at Gusen Camp

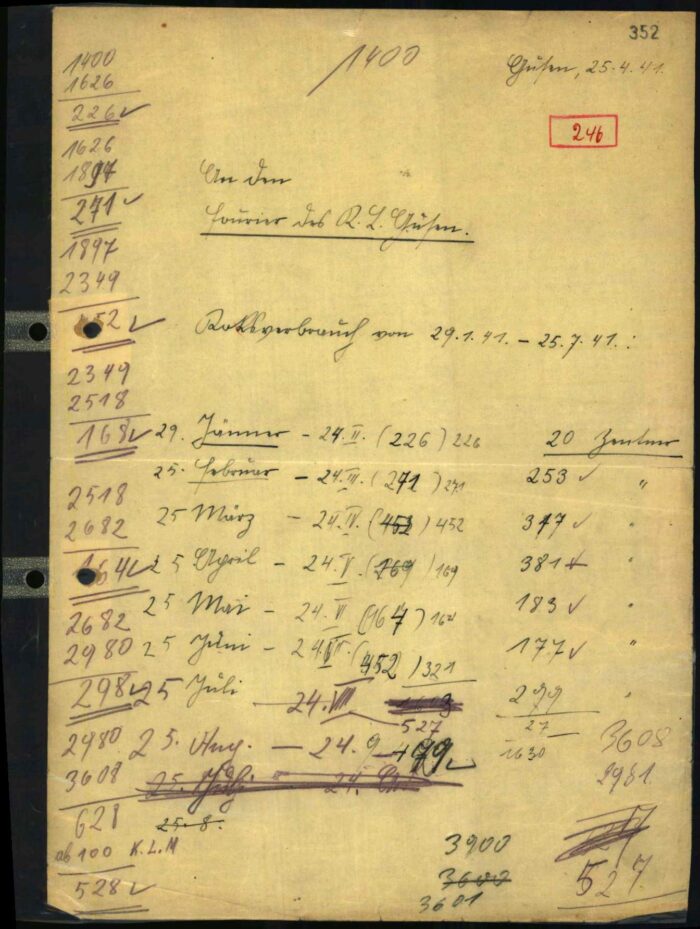

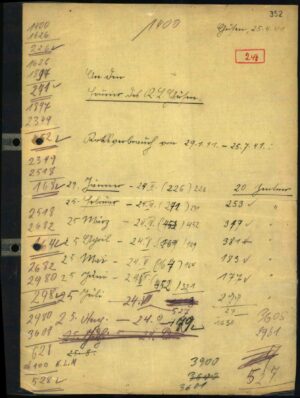

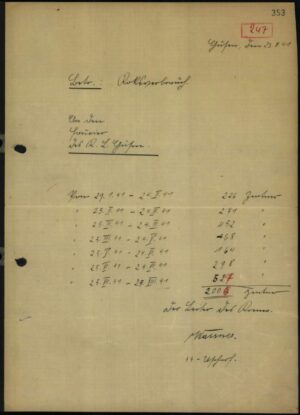

SS Unterscharführer Karl Wassner, head of the Gusen Camp’s crematorium, which was equipped with a coke-fired double-muffle furnace manufactured by the Topf Company,[11] drew up a series of reports that make it possible to accurately establish this furnace’s coke consumption for most of 1941.[12] I reproduce these documents, list their essential data, and comment on them.

The number “1400” at the center top of Document 1 indicates the facility’s coke consumption in centners[13] up to January 29, 1941. The column of figures on the left begins precisely with 1400; the next figure, 1626, is the total consumption up to February 24, and the one immediately below represents their difference (1626 – 1400 =) 226, a figure that constitutes the consumption of coke for the period of January 29 to February 24, 1941. The difference in the last pair of figures (3608 – 2980) is 628, but here, 100 centners were deducted with the justification “less 100 K.L.M” – meaning that this quantity of coke was probably transported to the Mauthausen Camp’s crematorium. Therefore, the actual consumption is 528 centners, but for unknown reasons, the figure given in the document is 527.

Next to the column just described are seven time periods that roughly correspond to the months of February to August. Next to each period, the respective coke consumption is noted. The column on the right, which begins with “20 Zentner,” contains data other than consumption.

In the following table, I summarize the data contained in this report.

| Cumulative Coke Consumption | Consumption During Each Period | Period in 1941 |

|---|---|---|

| 1626 – 1400 = | 226 | Jan. 29 – Feb. 24 |

| 1897 – 1626 = | 271 | Feb. 25 – March 24 |

| 2349 – 1897 = | 452 | March 25 – April 24 |

| 2518 – 2349 = | 168 | April 25. – May 24 |

| 2682 – 2518 = | 164 | May 25 – June 24 |

| 2980 – 2682 = | 298 | June 25 – July 24 |

| 3608 – 2980 – 100 = | 528 [527] | July 25 – Aug. 24 |

| Total: | 2106 |

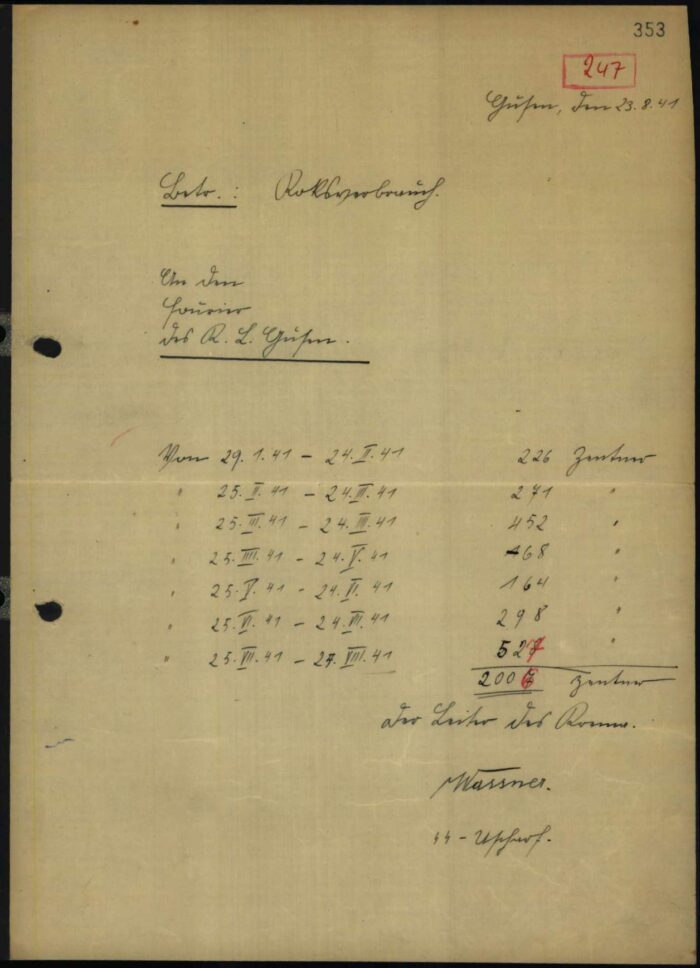

In Document 2, the coke consumption for the above-mentioned periods is shown as follows:

| Jan. 29 – Feb. 24 | 226 |

| Feb. 25 – March 24 | 271 |

| March 25 – April 24 | 452 |

| April 25 – May 24 | 68 |

| May 25 – June 24 | 164 |

| June 25 – July 24 | 298 |

| July 25 – Aug. 24 | 527 |

| Total: | 2006 |

|---|

As is clear from the previous report, the consumption of 68 centners for the period from April 24 to May 25 is incorrect; the correct figure is 168, and the total 2106.

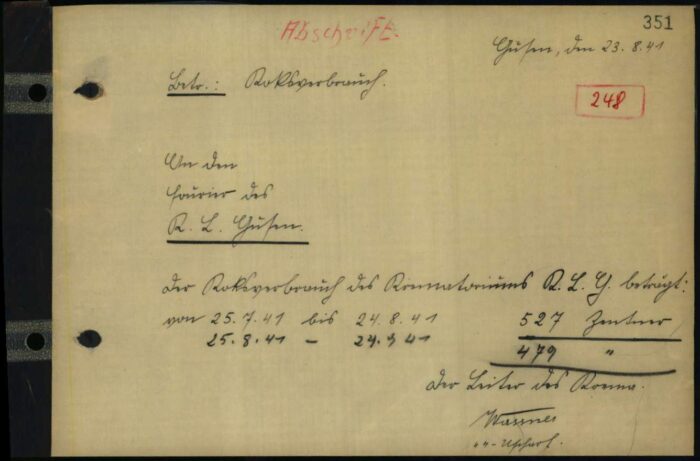

Document 3[14] is a report dated “Gusen, August 23, 1941” with the same addressee and subject as in the previous report. The text par states:

“The coke consumption of the Gusen Camp’s crematorium amounted to

from July 25, 1941 to Aug. 24, 1941 527 centners Aug. 25, 1941 to Sept. 24, 1941 479 ″ “

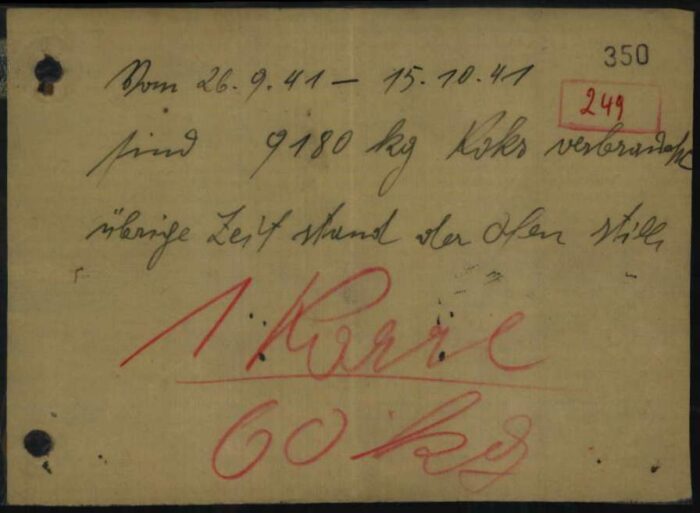

Document 4[15] is a brief note stating:

“From Sept. 26, 1941 to Oct. 15, 1941, 9180 kg of coke were consumed. The furnace was out of operation for the rest of the time”

At the bottom is a note in red pencil saying: “1 barrow 60 kg”.

Document 5, which I analyze in detail shortly, shows in addition to coke consumption by period, beginning with September 26, 1941, also the respective number of cremated corpses, which makes it easy to calculate the consumption per cremated corpse.

For the period from January 19 to September 24, however, only the consumption of coke is shown.

In an earlier study,[16] I tried to fill this gap by resorting to the list of deceased inmates at the Gusen Camp as published in the official history of the Mauthausen Camp.[17] However, the calculation, which was essentially correct, was based on figures for entire months, resulting in some inaccuracies for individual periods. With the Death Book (Totenbuch) of the Gusen Camp now at my disposal,[18] I can make more accurate calculations:

| Start Date 1941 | Serial No. in Death Book | Page No. in Death Book | End Date 1941 | Serial No. in Death Book | Page No. in Death Book | # of Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. 29 | 177 | 107 | Feb. 24 | 441 | 123 | 265 |

| Feb. 25 | 442 | 123 | March 24 | 742 | 141 | 301 |

| March 25 | 743 | 141 | April 24 | 1167 | 167 | 425 |

| April 25 | 1168 | 167 | May 24 | 1423 | 182 | 256 |

| May 25 | 1424 | 182 | June 24 | 1615 | 193 | 192 |

| June 25 | 1616 | 193 | July 24 | 1929 | 213 | 314 |

| July 25 | 1930 | 213 | Aug. 24 | 2405 | 241 | 476 |

| Aug. 25 | 2406 | 241 | Sept. 24 | 2893 | 271 | 488 |

| Total: | 2717 |

Subtracting from the final serial number (2893) the 176 deaths recorded up to January 28, 1941, gives precisely 2717 deaths.

In the following table, I summarize the general data for the period January 29 to September 24, 1941.

| Period 1941 | Coke Consumption [centners] | Coke Consumption [kg] | # Cremated Bodies | Average # daily cremations | Average Coke Consumption per Body |

| Jan. 29 – Feb. 24 | 226 | 11,300 | 265 | 10 | 42.6 |

| Feb. 25 – March 24 | 271 | 13,550 | 301 | 11 | 45.0 |

| March 25 – April 24 | 452 | 22,600 | 425 | 14 | 53.2 |

| April 25 – May 24 | 168 | 8,400 | 256 | 9 | 32.8 |

| May 25 – June 24 | 164 | 8,200 | 192 | 6 | 42.7 |

| June 25 – July 24 | 298 | 14,900 | 314 | 10 | 47.4 |

| July 25 – Aug. 24 | 527 | 26,350 | 476 | 15 | 55.3 |

| Aug. 25 – Sept. 24 | 479 | 23,950 | 488 | 16 | 49.0 |

| Totals: | 2,585 | 129,250 | 2,717 | 11 | 47.6 |

|---|

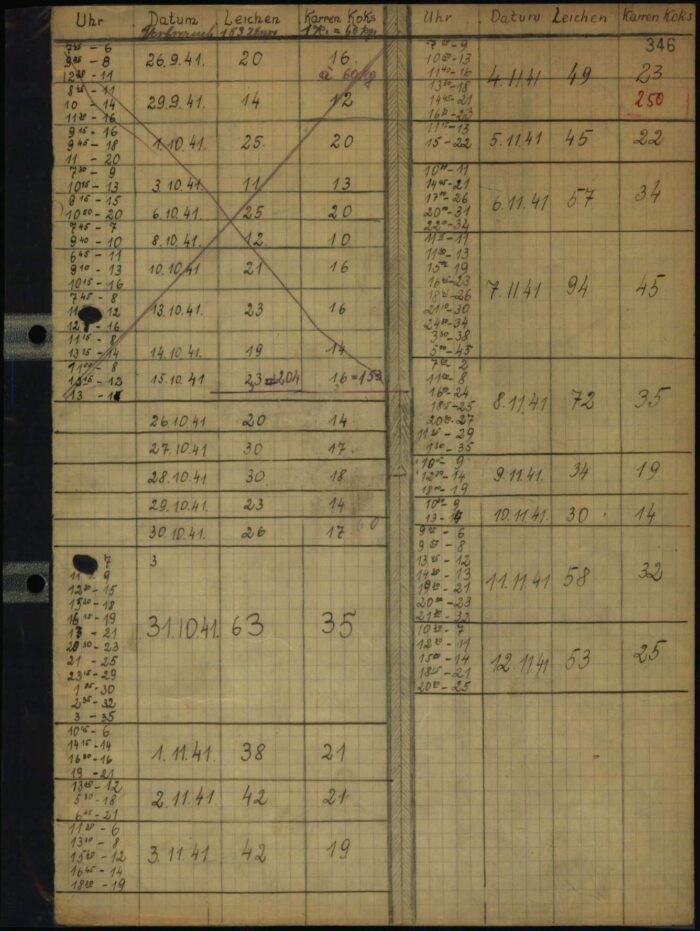

Document 5[19] is a table running over two columns containing data for the periods 26 September to 15 October, 26 to 30 October and 31 October to 12 November 1941. The table itself is divided into four columns: “Time” [“Uhr”], “date” [“Datum”], “Corpses” [“Leichen”] and “Barrows Coke 1 B. = 60 kg” [“Karren Koks 1 K. = 60 kg”]. I now analyze the individual periods.

a) First Period: September 26 to October 15, 1941

This table is crossed out with a large X. The “Uhr” column shows certain times for each day, and next to it progressive figures, indicating the number of barrows of coke discharged at the furnace from the coke storage at the indicated time. The “Datum” column carries the date of cremation, “Leichen” indicates the number of cremated bodies, and “Karren Koks” the number of barrows of coke used for cremation. The latter figure is correct only as of Oct. 1: at 9:16 a.m., a total of 16 barrows of coke = 960 kilograms had been unloaded, at 9:45 a.m., another 2 = 18 barrows total, at 11 a.m. still 2 = 20 barrows total, which is also the figure appearing in the fourth column.

For September 26 and 29, however, the number of barrows in the first column does not match the number in the fourth (26 Sept.: 11 in the first column, 16 in the fourth; 29 Sept.: 16 in the first and 12 in the fourth).

Also in the header, under “Datum” and “Leichen” a total “coke consumption 183 ctnr.” is noted, but the total is actually 153 centners.

Document 4 shows that the crematorium consumed 9,180 kilograms of coke during the period in question, corresponding to (9,180 ÷ 50 ≈) 183 centners, so this is the correct figure.

Undoubtedly because of these errors, the table was crossed out. The total number of cremated bodies (203) is identical with that of the Death Book, in which there are precisely 203 deaths recorded (Sept. 26: serial number 2894, p. 271; Oct. 15: serial number 3096. p. 283). It can therefore be considered certain that 203 corpses were cremated during the period in question consuming 9,180 kg of coke, or an average of 45 kg per corpse.

b) Second Period: 26 to 30 October 1941

The “Uhr” column is missing in this table. The other data are as follows:

| Date 1941 | Corpses | Barrows Coke | Coke Consumption [kg] | Average Coke Consumption per Corpse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct. 26 | 20 | 14 | 840 | 42.0 |

| Oct. 27 | 30 | 17 | 1,020 | 34.0 |

| Oct. 28 | 30 | 18 | 1,080 | 36.0 |

| Oct. 29 | 23 | 14 | 840 | 36.6 |

| Oct. 30 | 26 | 17 | 1,020 | 39.2 |

| Totals: | 129 | 80 | 4,800 | 37.2 |

c) Third Period: 31 October to 12 November 1941

The list for the period from October 31 to November 12, 1941 is the most important, because 677 cremations were carried out continuously over 13 consecutive days.[20] During this time, the furnace remained in constant thermal equilibrium, resulting in the lowest possible coke consumption, since the refractory masonry no longer absorbed heat, and heat loss by radiation, convection and conduction in the few hours of inactivity was insignificant.

The furnace was idle for repairs from October 16 to October 25, 1941. During that period, 127 inmates died (October 16: Death Book serial number 3097, p. 283; October 25: serial number 3223, p. 291); in the period from October 31 to November 12, the number of deaths was 593 (from serial number 3302, p. 297, to serial number 3894, p. 333). Therefore (677 – 593 =) 84 corpses were cremated, more than had died during that time, which means that most of those were also cremated who had died during the period when the furnace was out of service, and whose bodies undoubtedly had been stored in the crematorium’s mortuary.

I summarize the results of my calculations for this period in the following table, using the same method as used above.

| Date 1941 | Corpses | Barrows Coke | Coke Consumption [kg] | Average Coke Consumption per Corpse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct. 31 | 63 | 35 | 2,100 | 33.3 |

| Nov. 1 | 38 | 21 | 1,260 | 33.1 |

| Nov. 2 | 42 | 21 | 1,260 | 30.0 |

| Nov. 3 | 42 | 19 | 1,140 | 27.1 |

| Nov. 4 | 49 | 23 | 1,380 | 28.2 |

| Nov. 5 | 45 | 22 | 1,320 | 29.3 |

| Nov. 6 | 57 | 34 | 2,040 | 35.8 |

| Nov. 7 | 94 | 45 | 2,700 | 28.7 |

| Nov. 8 | 72 | 35 | 2,100 | 29.2 |

| Nov. 9 | 34 | 19 | 1,140 | 33.5 |

| Nov. 10 | 30 | 14 | 840 | 28.0 |

| Nov. 11 | 58 | 32 | 1,920 | 33.1 |

| Nov. 12 | 53 | 25 | 1,500 | 28.3 |

| Totals: | 677 | 345 | 20,700 | 30.6 |

In summary, we have:

- January 29 to September 24, 1941: Average consumption: 47.6 kg of coke: Average mortality was about 12 inmates per day.

- September 26 to October 15, 1941: Average consumption: 45 kg of coke. 193 cremations in a 20-day period, with 10 days of activity, so that on average cremations were performed every other day, and 19 bodies were cremated each day.

- October 26 to 30, 1941: Average consumption: 37.2 kg of coke. In a period of 5 days, 129 corpses were cremated. Cremations were performed daily; on average, 26 corpses were cremated each day.

- October 31 to November 12, 1941: Average consumption: 30.6 kg of coke. In a 13-day period, 677 corpses were cremated in continuous cremations; on average, 52 corpses were cremated in each cycle.

Thus, the operating results of the furnace were as follows:

| Period 1941 | Daily Cremations | Coke Consumption per Corpse |

|---|---|---|

| Jan. 29 – Sept. 24 | 12 | 47.6 kg |

| Sept. 26 – Oct. 15 | 19 | 45.0 kg |

| Oct. 26 – Oct. 30 | 26 | 37.2 kg |

| Oct. 31 – Nov. 12 | 52 | 30.6 kg |

I repeat: These are irrefutable empirical data, the only existing empirical data concerning a Topf crematorium for concentration camps.[21]

2) The Coke Consumption of the Topf Cremation Furnaces at Auschwitz and Birkenau

In this section, I examine to what extent the operating results of the Gusen furnace can be transferred to the furnaces at Auschwitz and Birkenau. In another study, I provided an accurate description of the structure and operation of the Topf cremation furnaces.[22] Below, I will summarize the essential data.

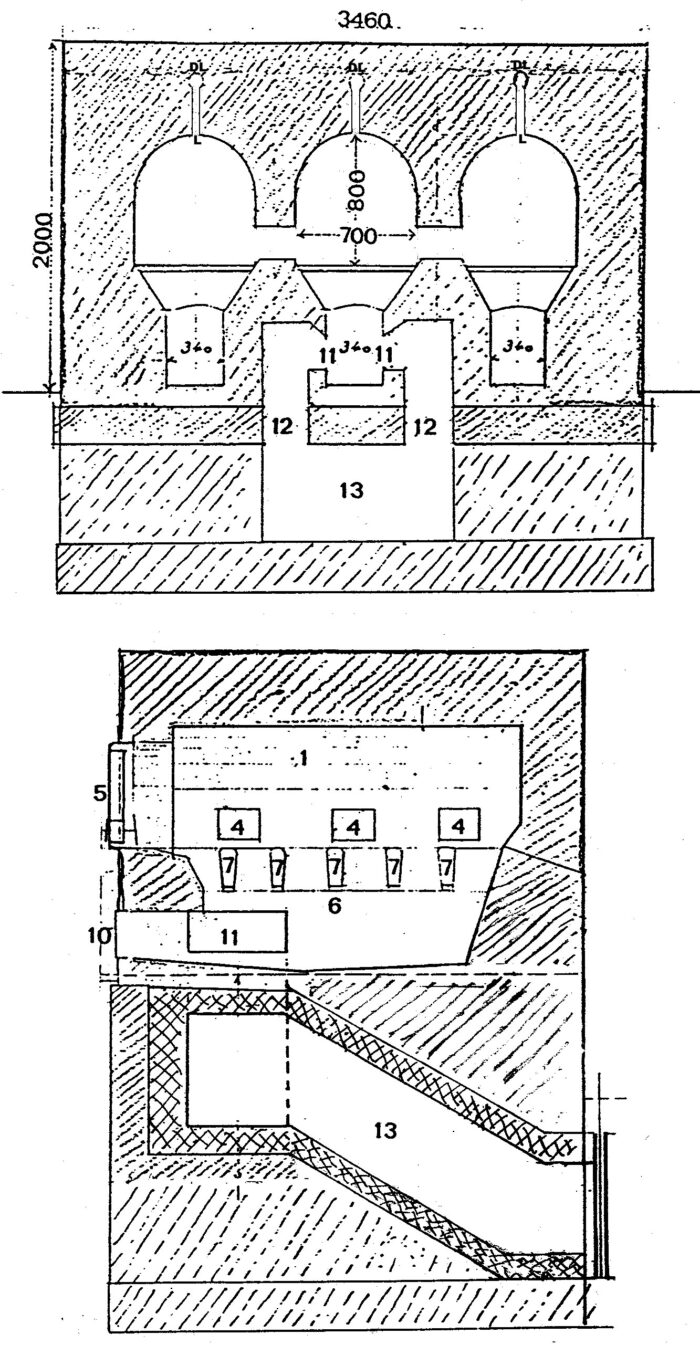

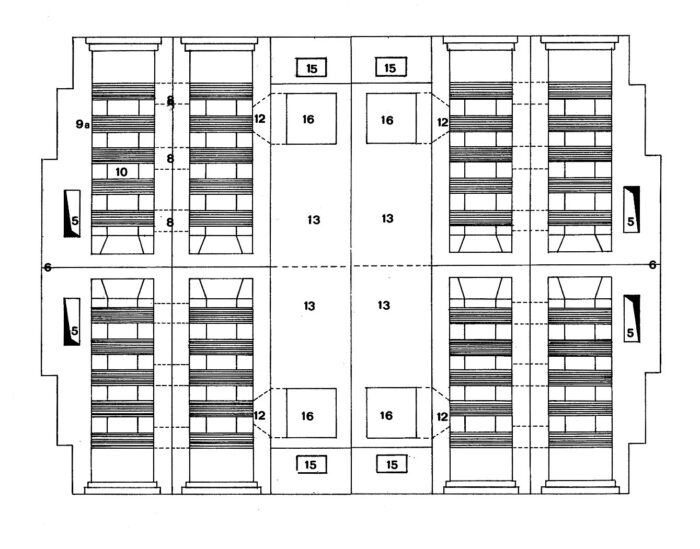

The Gusen cremation furnace was originally a mobile furnace heated with naphtha (“fahrbarer Ofen mit Ölbeheizung”) containing two muffles. It was later adapted to heating with coke by installing a coke-gas generator next to each muffle (see Document 6).[23]

It was ordered from Topf by the SS New Construction Office of the Mauthausen Camp on March 21, 1940, but on October 9, 1940, it was decided to change its heating system from naphtha to coke. Topf shipped the furnace by rail on December 12, 1940, and arrived at its destination on December 19. Assembly work began the same day, and was completed on January 22, 1941. The two coke-gas generators were installed during the construction of the furnace, which went into operation at the end of January.[24]

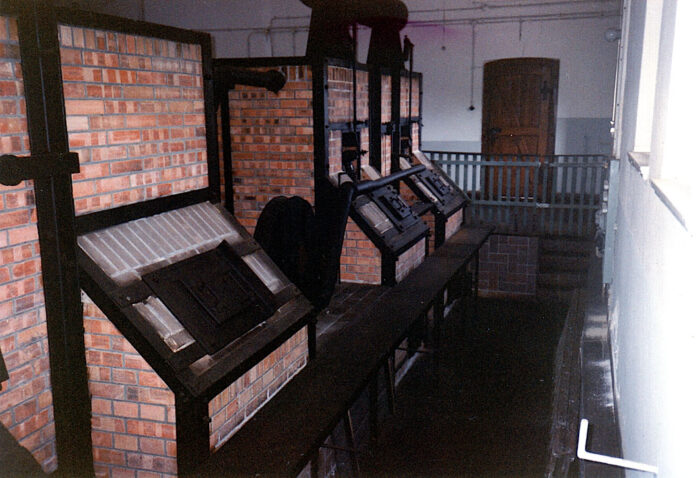

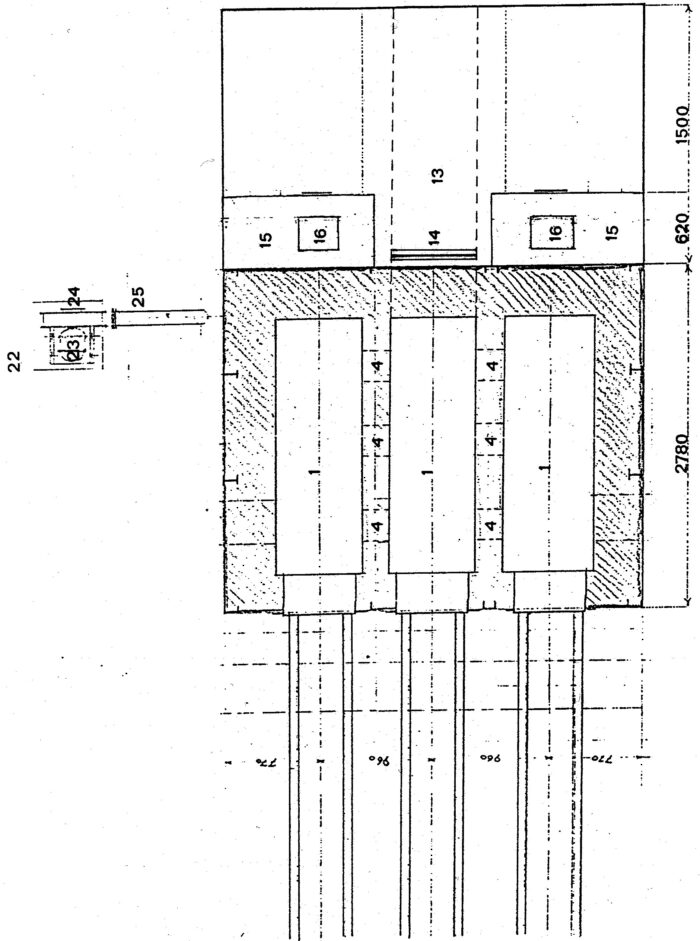

The Gusen Furnace constituted a refinement of the “Mobile cremation furnace system ‘Topf’” (“Fahrbarer Verbrennungsofen System ‘Topf’”) dating back to the early twentieth century. However, this device was conceived to burn animal carcasses. The three furnaces installed in the Auschwitz crematorium were a type patented on December 6, 1939 as the “Cremation furnace with two muffles” (“Einäscherungs-Ofen mit Doppelmuffel”). The cost estimate sent by Topf to the SS New Construction Office in Auschwitz on April 17, 1940 concerned precisely the “Delivery of a coke-fired Topf cremation furnace with double muffle and compressed-air system, and 1 Topf forced-draft system.” A furnace of this type was also installed in Mauthausen Camp in January and February 1945, which is the one that needs to be investigated when studying this furnace type (see Document 7),[25] because the Auschwitz furnaces had been disassembled by the SS in 1944 when they transformed the old crematorium into an “Air-raid shelter for the SS infirmary with a surgery room” (“Luftschutzbunker für SS Revier mit einem Operationsraum”). The furnaces rebuilt by the Poles after the war – using original elements that were stored in the camp warehouses – were assembled in a very flawed way, the most obvious error being the absence of the two gas generators in the rear (see Documents 8 and 9).

The Topf double-muffle furnace at Gusen Camp was structurally similar to the Topf double-muffle furnaces model at Auschwitz, but it had functional differences that slightly affected coke consumption. From the heat balance calculation on the basis of the technical data of the two devices and the empirically determined, certain coke consumption of the Gusen furnace, the following results for the Auschwitz double-muffle furnaces can be derived:

- 31.5 kg of coke for a lean corpse

- 28.0 kg of coke for a corpse with average weight loss

- 23.5 kg of coke for a normal corpse.[26]

Of course, the presence of normal corpses in a concentration camp must be ruled out in principle, so the relevant data points are the first two.

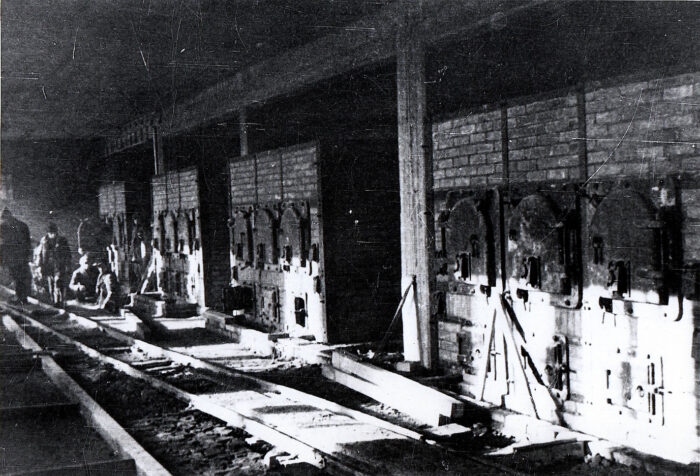

Crematoria II and III at Birkenau were equipped with five furnaces with three muffles each. They were dismantled by the SS in 1944, and there are only two photographs from the earlier period that depict them quite clearly (see Documents 10 and 11). Two furnaces of this model were also installed inside the Buchenwald Camp’s crematorium, one in May, the other in August 1942. The two devices (one also equipped for heating with naphtha), which are in general in a good state of preservation, provide insight into the structure and operation of the Birkenau furnaces as well (see Document 12).

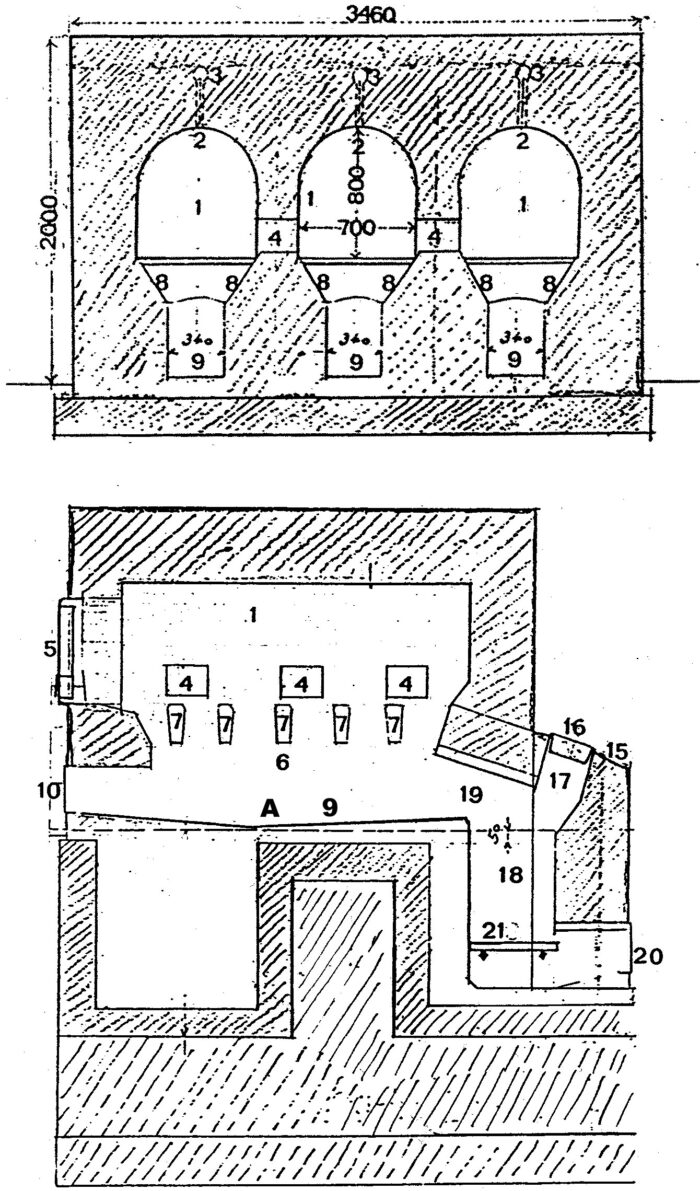

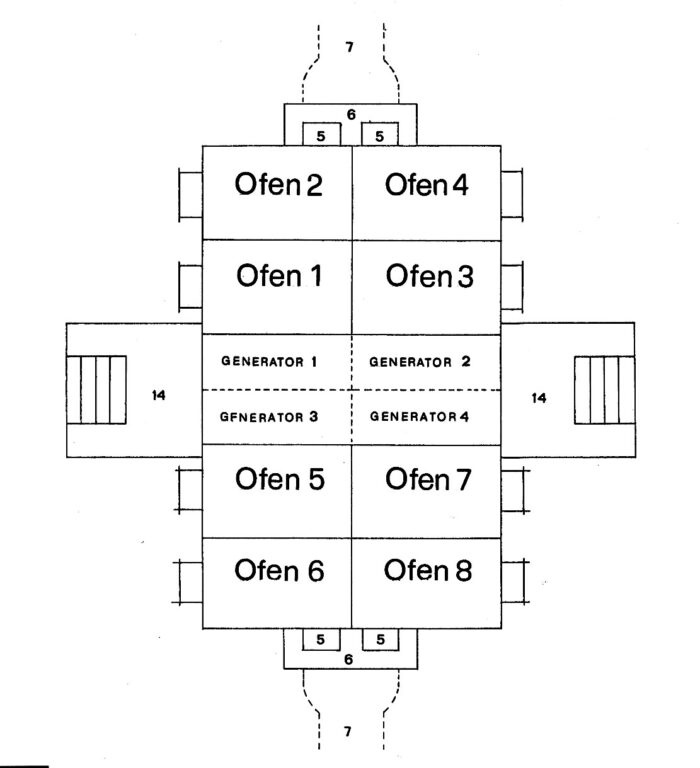

The triple-muffle furnace (Dreimuffel-Einäscherungsofen) consisted of a double-muffle furnace with an additional third central muffle, and was heated by two gas generators, which were located behind the two lateral muffles (see Document 13). These behaved like a double-muffle furnace, but discharged their fumes into the central muffle (see Document 14). Since the furnace operated with a relatively high excess of air, the fumes from them contained a certain percentage of oxygen that, according to the designer’s expectations, was to be used for the combustion of the corpse in the central muffle. This in turn was meant to result in some fuel savings.

However, this presupposes first of all that the muffles were loaded in a staggered manner: first the two lateral ones and, after about half an hour, when the main combustion of the two corpses with heat development began, the central muffle. In this way, the heat produced by the two lateral corpses would be used for the vaporization of the corpse in the central muffle. There is no trace of such a practice in the witness statements, however. If all three muffles were loaded in rapid succession (the method described by the witnesses), there would have been a concurrent lowering of temperature in all three muffles during the initial vaporization phase, but it would have been more pronounced in the central one, due to the confluence of gas and water vapor at a lower temperature from the two lateral muffles. In the main combustion phase, on the other hand, there would have been an excess of heat produced. In practice, therefore, the heat produced by the two lateral bodies would have been largely lost. This excess heat could in fact be stored only to a small extent in the refractory masonry, which had a rather small mass compared to that of a civilian furnace (see Subchapter 5).

The heat balance I calculated in my study of the Auschwitz crematoria – corresponding to a coke consumption of 22 kilograms for a lean corpse and 19 kilograms for one with average weight loss – is therefore the theoretical minimum, as indeed I had pointed out.

The file memo (Aktenvermerk) dated March 17, 1943, written by civilian employee engineer Rudolf Jährling of the Auschwitz Central Construction Office, sets forth an estimate of the coke consumption for the Birkenau crematoria for 12 hours of daily operation.[27] Crematoria II and III each had five triple-muffle furnaces with 10 gas generators, whose hearths consumed 350 kg of coke per hour (meaning 35 kg/h per hearth), thus (350 kg/h × 12 h =) 4,200 kg in 12 hours per crematorium, 8,400 kg for both.

Crematoria IV and V each possessed an eight-muffle furnace with four gas generators, each of which consumed 140 kg of coke per hour (again 35 kg/h per hearth), 1,680 in 12 hours, 3,360 for both crematoria of this type. Jährling stated that in the case of continuous operation of the furnaces (“bei Dauerbetrieb”) – assuming 12 hours of daily operation – the consumption decreased by one third, so the 12-hour consumption of Crematoria II and III was 2,800 kg, that of Crematoria IV and V 2,240 kg of coke, in total 7,840 kg.[28]

As the operating results of the Gusen furnace clearly show, this reduction depended on the fact that, under such circumstances, the furnaces cooled less due to shorter periods when they were not in operation. Hence, less coke was needed to bring them back to operating temperature. In fact, continuous operation of the furnace, compared to discontinuous operation, resulted in fuel savings of (30.6 ÷ 47.6 =) 64.3% or (30.6 ÷ 45 =) 68%; in practice, a savings of one third.

This comparison clearly shows that Jährling’s approach to calculations was flawed, as he always contemplated 12-hour furnace operation, without considering preheating hours. This leads to the absurd consequence that, in discontinuous operation, a triple-muffle furnace consumed in 12 hours (70 × 12 =) 840 kg of coke, and in continuous operation [(70 × 12 =) × (2 ÷ 3 =)] 560 kg, which would correspond to a reduction in hourly coke combustion on the grate of the hearths of (560 ÷ 12 =) 46.6 kg instead of 70 kg. This consumption, however, depended directly on the chimney draught: it could increase (in the case of forced draught or, for a very short time, in the case of exceptionally high combustion temperatures in the muffles), but not decrease, except insignificantly, by reducing the inflow of combustion air into the gas-generator hearth. This airflow could not be turned off and on as needed, unlike a naphtha or gas burner.

Therefore, the correct reasoning looks as follows: Assuming a consumption of (70 × 12 =) 840 kg/h of coke for a triple-muffle furnace in 12 hours of operation per day every day and (70 × 6 =) 420 kg for 6 hours of reheating in the case of discontinuous operation (e.g., once a week), but still for 12 hours of operation, the total consumption would be (420 + 840 =) 1260 kg; in the former case, the consumption would be (840 ÷ 1260 =) 66.7% of the latter, or about 2/3, with a saving of precisely one third.

This clarified, since, according to the data of cremation technology of the time and the statements of the Topf engineers who designed the three-muffle furnace – Kurt Prüfer – and its blower – Karl Schultze – the duration of the cremation process in this plant was one hour,[29] the total coke consumption could not be less than what burned in one hour on the grates of the gas-generator’s hearths, meaning (35 + 35 =) 70 kg, thus (70 ÷ 3 =) 23.3 kg per cremated corpse.

In practical terms, it is necessary to define exactly what is meant by the duration of the cremation process. In civilian furnaces, in which, by law, the second corpse could be introduced into the muffle only after the ashes of the first had been extracted from the furnace, the duration of cremation was precisely the time between the introduction of the corpse into the furnace and the extraction of its ashes.

In Topf’s double-, triple- and eight-muffle furnaces, on the other hand, the second corpse was introduced into the muffle as soon as the still-combusting remains of the first had fallen into the ash chamber below, where the afterburning took place. This procedure was explicitly stated by the manufacturer in the “Operating Instructions for the coke-fired Topf Triple-Muffle Crematorium Furnace” (“Betriebsvorschrift des koksbeheizten Topf-Dreimuffel-Einäscherungsofen”):[30]

“As soon as the corpse parts have dropped from the fireclay grate onto the inclined ash-plate below, they must be moved forward towards the ash-removal door by means of the scraper. These parts may remain here for another 20 minutes for post-combustion. Then the ash is transferred into the ash container and set aside for cooling.

In the meantime, new corpses will be introduced successively in the chambers.”

The most appropriate comparison in practical terms are the results of a series of scientific cremation experiments carried out between 1926 and 1927 by engineer Richard Kessler in the Dessau Crematorium, equipped with a coke-fired furnace (also equipped for gas reheating). During experiments with coke heating, the peak of the main combustion in the muffle furnace (maximum combustion temperature: 893°C) occurred after 55 minutes. Since the total duration of the cremation process averaged 86 minutes, the remains of the corpses continued to burn with an open flame for another 5-10 minutes, then became embers that burned for another 20-25 minutes. According to the aforementioned “Service Instructions,” this process lasted about 20 minutes in the Topf triple-muffle furnace. It is not known with certainty after how long the corpse parts fell “from the fireclay grate onto the inclined ash-plate below,” which was in any case after reaching the peak of the main combustion. Therefore, the duration of the cremation process of one hour can be considered the minimum lower limit, all the more so since the corpses used by engineer Kessler were normal. Those destined for the Topf furnaces, on the other hand, were more or less emaciated and therefore not as combustible.

Moreover, the triple-muffle furnace had only one smoke damper for three muffles and one blower (Druckluftgebläse) serving all three muffles, meaning the air flow could not be adjusted individually for each muffle. Therefore, running individual muffles was impossible: any operation carried out on the gas generators, combustion air (blower) and smoke damper would affect all three muffles simultaneously.

The furnace could function well only in the event that the combustion process in the three muffles was fairly uniform, but this is already ruled out by the furnace design, since the corpse placed in the central muffle was necessarily in different thermotechnical, chemical and physical conditions (temperature, composition of combustion products/fuel gases from the lateral muffles, volumetric velocity of passing combustion products through the central muffle). Not to mention that it would have been extremely difficult to find, from time to time, three bodies with the same degree of combustibility.

Given these characteristics, it is virtually impossible that the triple-muffle furnace (operated by simple inmates) could have matched the performance of the Dessau furnace conducted by a trained engineer.

Therefore, the duration of the cremation process in the triple-muffle furnace of one hour with a consumption of 23.3 kilograms of coke per corpse can be considered an entirely exceptional lower limit.

As a realistic point of reference, one can take the minimum consumption of the Gusen furnace during the period of the most frequent cremations, namely 27.1 kg of coke per corpse (on November 3, 1941). In the triple-muffle furnace this corresponds to the cremation of three corpses in about 70 minutes.

The coke-fired Topf eight-muffle cremation furnace consisted of eight single-muffle furnaces, conforming to the design of Topf blueprint D 58173, grouped in two sets of four furnaces; each group consisted of two pairs of furnaces arranged in reverse, so that each pair had in common the two bottom walls and the two middle walls of the muffles, according to the system already adopted by Topf in the two furnaces of the Płaszów Camp’s crematorium. The two groups of furnaces were connected by four gas generators coupled with the same system, so that they formed a single eight-muffle furnace appropriately named “large-size cremation furnace” (“Grossraum-Einäscherungsofen”; see Document 15). In this furnace model, one gas generator served two muffles, so the combustion gases passed through the first muffle and then, together with the products of corpse combustion, through the second. But even then, to take advantage of this excess heat, it would have been necessary to stagger the cremations, that is, to introduce a corpse into the second muffle when the one in the first was in the main combustion phase.

If one reasons by analogy using the data in the file memo mentioned earlier, one might conclude that, since the hearths of the four gas generators in the eight-muffle furnace could burn 140 kg of coke, the consumption per cremation would be (140 ÷ 8 =) 17.5 kg. However, this is unrealistic for various technical reasons related to its design. The device’s design required the flow of gases from the gas generator to hit the corpses laterally, instead of from head to toe, as was the case in the two lateral muffles of the triple-muffle furnace (in the central muffle, the corpse was hit by the flow of gases from both sides).

The eight-muffle furnace was not equipped with a blower, so any possible lack of combustion air could not be quickly remedied, and it was also equipped with only one smoke-duct damper (Rauchkanalschieber) for four muffles, which made it impossible to conduct the cremation process efficiently by adjust for each individual corpse the chimney draught and consequently the gas-generator hearth throughput.

Structurally, a pair of muffles in an eight-muffle furnace corresponded to a lateral muffle and a central muffle of the triple-muffle furnace, so the heat produced by the second lateral muffle in the triple-muffle furnace was missing in the eight-muffle furnace. In schematic terms, we have the situation as summarized in the following table:

| Triple-Muffle Furnace | Eight-Muffle Furnace | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lateral muffle | central muffle | lateral muffle | lateral muffle | lateral muffle | |

| gas generator (35 kg/h) + corpse → |

corpse ↓ chimney |

gas generator (35 kg/h) + ← corpse |

gas generator (35 kg/h) + corpse → |

corpse → chimney |

|

Lacking the heat input of one muffle (gas generator + corpse), it is obvious that the coke consumption of the eight-muffle furnace could not be less than that of the triple-muffle furnace. Assuming the same consumption (27.1 kg of coke), the cremation duration would be about 80 minutes, which is quite realistic.

Be that as it may, in the economics of an assumed mass cremation, the 8-muffle oven is practically irrelevant, because the two such ovens installed in Crematoria IV and V at Birkenau worked very little in relation to those in Crematoria II and III. According to Jean-Claude Pressac, the ovens in these two crematoria cremated about 20,000 corpses.[31] On the other hand, Robert Jan van Pelt asserts that about 500,000 bodies were cremated in Crematorium II alone.[32]

When it comes to Holocaust claims, the essential reference figure is thus the consumption of about 27 kg of coke per cremation for the triple-muffle furnace when in thermal equilibrium. This clarification is of fundamental importance, because constant thermal equilibrium was most certainly not given, already because of the numerous suspensions of operations that were necessary for furnace repairs,[33] but also for the periods when Jewish transports (and thus alleged gassings) were rather small.[34]

How much this affected the consumption of coke is clear from the data on the Gusen furnace I have outlined earlier: depending on the frequency and number of cremations, the consumption of coke varied from 30.6 to 47.6 kg per corpse.

Obviously, the longer a furnace was idle, the more it cooled down, and the greater amount of fuel was needed to bring it up to operating temperature (800°C), and this amount was added to the amount needed for the actual cremations, increasing the average consumption.

In the very favorable case of the average consumption of 37.2 kg of coke (13 corpses per day per muffle; see Table 7), the increase, compared to the minimum consumption (30.6 kg) was (37.2 ÷ 30.6 =) 121%. Therefore, the coke consumption of the triple-muffle furnaces after a long period of cooling can be considered as a minimum of (27 × 1.21 =) 32.7 kg per cremation.

Robert Jan van Pelt drew the below conclusion from the above-mentioned file memo and the letter from the Auschwitz Central Construction Office dated June 28, 1943[35] (which attributes the absurd cremation capacity of 1,440 “persons” (sic) to each of Crematoria II and III, and 768 to each of Crematoria IV and V):[36]

“The capacity of the crematoria was calculated on a 24-hour basis as being 1,440 for Crematoria 2 and 3 and 756 for Crematoria 4 and 5, or ([1,440 + 1,440 + 756 + 756]/24) = 183 corpses per hour. This implies that, according to Jährling, on average one needs (654.3/183) = 3,5 coke to incinerate one corpse.”

The small error (756 instead of 768) does not affect the result of the calculation, which is given as follows:

([1,440 + 1,440 + 768 + 768]/24) = 184 corpses per hour.

The hourly of consumption was (7,840 ÷ 12 =) 653.3 kg, so the requirement for one corpse was (653.3 ÷ 184 =) 3.55 kg of coke. This technically and empirically nonsensical consumption (it is six to seven times less than the actual consumption) moreover refers to the continuous operation of the furnaces, which van Pelt, with an inadmissible logical leap, considers to be valid for an entire year – which, as noted earlier, makes no sense, because even from the orthodox Holocaust perspective, there were many days during which no gassing/cremations are said to have been being carried out:[37]

“as coke delivery in 1943 was around 844 tons, this would have allowed for the incineration of 241,000 bodies. According to Piper’s calculations based on transport lists, around 250,000 people died in Auschwitz in 1943.”

In practice, this would be a historical “confirmation” of the validity of the claimed consumption of 3.5 kg per corpse (844,000 ÷ 3.5 = 241,142).

By so doing, van Pelt effectively demolished the orthodox Holocaust narrative of mass gassings/cremations at Auschwitz-Birkenau, because even if we were to assume the incorrect figure of 844 tons of coke delivered, the result would be (844,000 kg ÷ 32.7 kg/corpse ≈) 25,800 cremated corpses!

In fact, as I documented in another study,[38] in 1943 (from March 14 to October 25)[39] merely 607 tons of coke were delivered to the crematoria at Auschwitz-Birkenau, plus 96 cubic meters of firewood (equivalent to about 43 tons of wood, and thus some 21.5 tons of coke). According to another source, further 44.5 tons of wood (roughly equivalent to 22.2 tons of coke) were delivered. Adding the above 607 tons to the coke equivalents of the wood (43.7 tons) yields fuel equivalent to about 651 tons of coke, with which (651,000 kg ÷ 32.7 kg/corpse ≈) some 19,900 corpses could have been cremated!

From March 14 to October 25, 1943, about 15,000 inmates died in round numbers,[40] so that the coke consumption per corpse was (651,000 kg ÷ 15,000 corpses ≈) 43.4 kg. This value falls between the second and third cases of the Gusen furnace consumption summarized in Table 7, 37.2 and 45.0 kg of coke per corpse, respectively, which confirms the total compatibility of coke supplies with the mortality of registered inmates. However, it categorically excludes the possibility of cremations of the alleged gassing victims. For these victims alone – about 116,800 are claimed for the aforementioned period – ([116,800 × 32.7 kg/corpse] ÷ 1,000 kg/t ≈) 3,819 tons of coke would have been needed.

This figure of 116,800 claimed gassing victims consists mostly (about 111,600) of the difference between those deported to Auschwitz and those registered there (the remainder would be the result of alleged “selections” of registered inmates). Hence, either all non-registered deportees were gassed and cremated – which is impossible due to a lack of fuel – or they were all transferred alive from Auschwitz, which is the only possible conclusion.

But the above-mentioned empirical data are even more devastating for orthodox Holocaust historiography, because they also demonstrate the utter absurdity and thus the falsehood of “eyewitness” statements.

Henryk Tauber – the quintessential witness regarding the alleged events unfolding in Crematoria II and III at Birkenau – stated that an average of 2,500 corpses per day were cremated in Crematorium II,[41] and that a workday consisted of an average of 21 hours,[42] because an operational pause was needed every day to clean the grates of the gas-generator hearths. This operation can be equated with that of the Gusen furnace during the period from October 31 to November 12, 1941, meaning that the furnaces can be considered practically to have been in constant thermal equilibrium. Hence, the minimum consumption of 27.1 kg of coke per cremated corpse applies.

According to Tauber (and van Pelt), however, this consumption was [(35 kg coke/hearth × 2 hearths) × 5 furnaces × 24 hours =] 5,600 kg/day ÷ 2,500 corpses/day = 3.1 kg per corpse!

In his article “The Supply of Materials to the Crematoria and Gas Chambers at Auschwitz: Coke, Wood, Zyklon,” Polish Auschwitz historian Piotr Setkiewicz stated that “in total no more than 800,000 corpses were cremated in the Birkenau crematorium.”[43] This would mean that, over a period of 31½ months, these furnaces should have received ([800,000 × 32.7 kg/corpse] ÷ 1,000 kg/t ≈] 20,928 tons of coke. However, the documented quantity for the period from March 14 to October 25, 1943, hence just over seven months, was 607 tons, plus 87.5 tons of wood (equivalent to about 44 tons of coke). Therefore, as noted earlier, an equivalent supply of 651 tons of coke can be considered, not some 21,000.

3) Multiple Concurrent Cremations in One Muffle[44]

The simultaneous cremation of two or more corpses in a muffle was prohibited by German law. However, if a mother and her child died in childbirth, their bodies could be cremated together. For concentration-camp crematoria, there are no documented cases of multiple cremations of adults.[45] Therefore, the operating results of animal-carcass incineration furnaces are crucial to the study of this question, in particular those built by the Hans Kori Company in Berlin.

This company manufactured eight different types of furnaces of increasing size and capacity. In the following table, I compare the smallest model (named 1a) and the largest (4b):[46]

| External Dimensions [mm] | Grate Dimensions [mm] | Capacity1 [kg] | Hard Coal2 [kg/h] | Duration3 [h] | Furnace Mass [kg] | ||||

| 1a | 1160 | 2460 | 2200 | 400 | 1700 | 250 | 110 | 5 | 950 |

| 4b | 1680 | 3630 | 3100 | 920 | 2900 | 900 | 300 | 13,5 | 2000 |

| 1 Capacity of furnace, filled once. 2 Hard coal consumption at full capacity. 3 Duration of incineration at full capacity. |

|||||||||

From this it appears that, by changing from an furnace with a grate area of (0.4 m × 1.7 m =) 0.65 m² to one with a grate area of (0.92 × 2.9 =) 2.7 m², in other words by increasing the grate area by (2.7 ÷ 0.65 =) 4.2 times, the coke consumption increased by a factor of (300 ÷ 110 ≈) 2.7, and the duration of the combustion also by a factor of (13.5 ÷ 5 =) 2.7.

This figure already renders absurd the claim of all the “witnesses” of the so-called “Sonderkommando” that, by loading multiple corpses into the same muffle (i.e., with the same volume, grate and hearth area), the cremation duration and coke consumption remained unchanged, meaning that they were the same as those required for the cremation of a single corpse.

This thermotechnical absurdity is explicitly stated by Robert Jan van Pelt on the basis of a letter from the Auschwitz Central Construction office dated June 28, 1943.[47] This document claims that the cremation capacity of one muffle of the triple-muffle furnace was (1440 corpses/day ÷ 15 muffles =) 96 corpses per day, or four corpses per hour. Franciszek Piper went even further by asserting:[48]

“Sonderkommando survivors recall that in practice three to five corpses were burned at a time [in 30 minutes]. This doubled the ‘capacity’, bringing it up to around 8,000 corpses per day”.

This corresponds to an hourly capacity of seven corpses per muffle! It should be made clear that the animal-carcass incineration furnaces mentioned earlier were designed specifically for the indicated loads. It is furthermore obvious, already for commercial reasons,[49] that model 1a could not have had the same performance as model 4b simply by loading 900 kg of organic matter into it instead of 250.

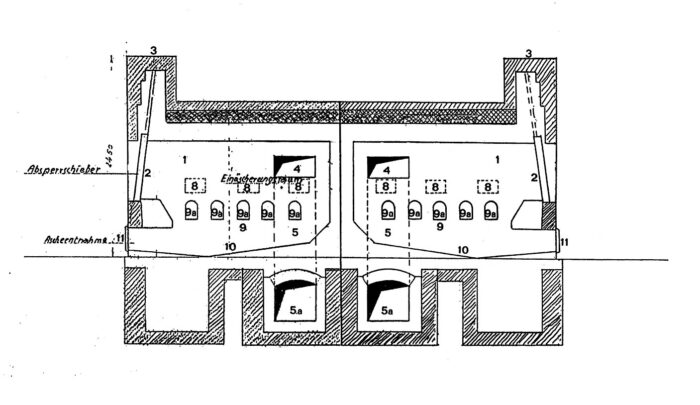

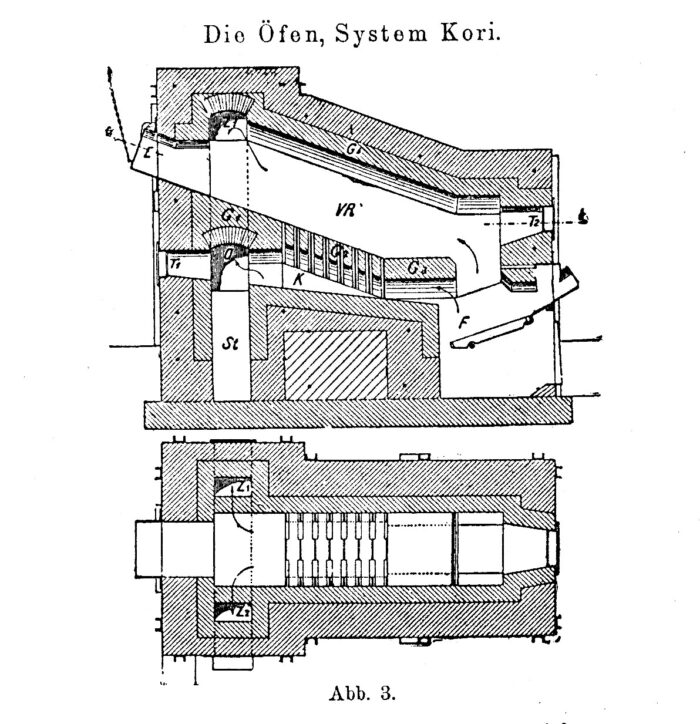

The design of this model (see Document 16) also applied to the others, in which, overall, only the dimensions varied. The procedure was simple and straightforward: the grate [F] of the combustion chamber [VR] was inclined, so the gases produced by the gas generator engulfed the organic matter from the bottom to the top, and the fumes flowed into the chimney through two openings arranged at the top of the chamber [Z1 and Z2].

In Topf furnaces, on the other hand, the gases from the gas generator and the fumes followed a circuitous route. In the triple-muffle furnace (see Documents 14-1, 14-2, and 14-3), each of the two lateral muffles had a gas generator [18]. The coke burning on the hearth grate [21] produced combusted and combustible gases that engulfed the corpse, usually positioned on the grate [7] with its head forward, from above and below (under the grate), lengthwise. From there, they were sucked by the chimney draught into the central muffle through the three inter-muffle openings [4], where they flowed over the right and left flanks of the corpse placed there, and then into the smoke duct [13] through two openings [11] located on either side of the ash compartment [12]. Thus, the gases had to take a 90° turn vertically to enter the muffle, then 90° horizontally to enter the central muffle, and 90° vertically again to enter the smoke duct. The procedure worked well by cremating only one corpse per muffle, because the furnace was designed precisely for this.

The three inter-muffle openings measured 30 cm × 20 cm, and their upper edge was 35 cm above the grate plane. The introduction of four to seven corpses into each muffle would therefore have inevitably obstructed – significantly or completely – these openings from both sides (from that of the lateral and the central muffle), obstructing the passage of gases. The corpses placed in the central muffle would also have largely obstructed the gaps of the grate (which remained largely free when only one corpse was placed there), obstructing the passage of combustion gases into the smoke duct beneath.

In the aforementioned Kori furnaces, on the other hand, the organic matter was always directly and in one direction engulfed by the combustion products from the hearth. Furthermore, as this organic matter burned and shrank, it slid by gravity along the sloping grate of the muffle, and thus was constantly approaching the hearth.

Given these facts, van Pelt and Piper’s claims, are not just absurd, but appear utterly ridiculous.

In conclusion, since the history of gassings in the Birkenau crematoria is intricately connected to the history of cremations, the practical impossibility of mass cremation is equivalent to the practical impossibility of mass gassing.

4) The Durability of the Muffles’ Refractory Masonry.[50]

In an article published on October 25, 1941, German engineer Rudolf Jakobskötter noted the following when describing the third Topf electric furnace at the Erfurt crematorium:[51]

“Since over 3000 cremations have been carried out in the second electric furnace in Erfurt, whereas the muffles had previously only withstood around 2000 cremations, depending on their design, it can be said that the design has fully proven itself in terms of durability. The manufacturing company expects each muffle to last for 4000 cremations in the future.”

In a summary table, he reported the number of cremations and the monthly energy consumption of the three electric crematoria built by the Topf company:

- First furnace: January 1934 to November 1935: 1,294 cremations

- Second furnace: July 1935 to October 1939: 2910 cremations

- Third furnace: January 1940 to April 1941: 2700 cremations[52]

The figure of 3,000 cremations was thus a generous rounding up, and that of 2,000 cremations evidently referred to the earlier coke-fired furnaces. Compared to a muffle of the Topf furnaces for concentration camps, these civilian electric furnaces, had a vastly higher refractory mass (see next paragraph), which also corresponded to a longer service life, as is evident from the perfectly documented case of the Gusen furnace. It went into operation on January 29, 1941, but already by the end of September, its refractory masonry was so badly deteriorated that it had to be replaced.

On September 24, the Mauthausen Construction Office asked Topf to send an installer immediately to repair the furnace.[53] Topf sent installer August Willing, the same man who had built the device. The latter arrived in Gusen on October 11, and set to work the next day. The relevant documents show that the work was carried out from October 12 to November 9, 1941. In the week of October 16 to 22, in 68 hours of work, he replaced the refractory masonry of the furnace; in the following week, in 68 hours of work, he completed the reconstruction of the masonry enveloping the furnace, and performed a test cremation. Willing remained in Gusen until November 9 to fine-tune the furnace and supervise its operation.[54]

From January 29 to October 15, 1941, the last day the furnace could operate, it cremated 2,921 corpses,[55] hence less than 1,500 per muffle. This is perfectly in line with the 2,000 cremations for civilian furnaces.

But even if one were to attribute this figure to the Birkenau crematoria as an extreme limit, it would result in a total potential capacity of (46 muffles × 2000 cremations =) 92,000 cremations.

Consequently, returning to van Pelt’s and Setkiewicz’s assertions quoted earlier, the alleged 500,000 cremations in Crematorium II would have required replacement of the refractory masonry of all 15 muffles by (500,000 ÷ [15 muffles × 2000] ≈) 16 to 17 times, or of all 46 muffles by (800,000 ÷ [46 × 2000] ≈) 8 to 9 times.

These works would have involved an enormous amount of paperwork (orders, cost estimates, sending installers, assembly costs, etc.), but there is no trace of them in the voluminous correspondence between Topf and the Auschwitz Central Construction Office. One cannot appeal to documentary gaps in this regard either, because the existing documents allow one to reconstruct the complete picture of the invoices for the work performed by the Topf Company at Auschwitz-Birkenau.[56] Not a single invoice covers the replacement of refractory masonry of even a single muffle.

Records show only that in early December 1941 the Central Construction Office had ordered a wagonload of refractory “as replacement materials for repair work”[57] for the repair of the second furnace of the crematorium at the Auschwitz Main Camp. Considering the replacement of the refractory masonry of two muffles, the furnaces of this crematorium could have cremated a maximum of 14,000 corpses. Therefore, the total number of corpses that could have been cremated in the furnaces of Auschwitz-Birkenau is approximately (92,000 + 14,000 =) 106,000.

5) Technical Remark

The furnace made by the company Beck Brothers, used by engineer Richard Kessler for his cremation experiments, had a refractory mass of at least 12,000 to 13,000 kilograms, which allowed for considerable heat buildup. In the Topf double-muffle furnace, the refractory mass was 10,000 kg, 5,000 kg per cremation unit (muffle/gas generator), and the maximum operating temperature was 1100°; in the triple-muffle furnace, the refractory mass was about 11,500 kg, hence only about 3,850 kg per cremation unit, with a maximum temperature of 1000°C; in the eight-muffle furnace, it was 24,100 kg, about 3,000 kg per cremation unit, with a maximum temperature presumably also of 1000°C.[58]

The refractory grate (Schamotte-Roste) of one muffle of the Gusen furnace consisted of three transverse bars, spaced about 30 cm apart, and one longitudinal bar placed in the middle, forming a grate plane with eight rectangular openings of about 30 cm × 25 cm. In contrast, the grate of the Topf triple-muffle furnace consisted of five transverse bars placed at a distance of about 20 cm. As a result, larger corpse parts could drop through the grate of the Gusen furnace into the ash compartment. Consequently, the muffle cleared earlier, with the main combustion not wrapping up in the muffle, but in the ash compartment. This made it possible to reduce the practical cremation time in the muffle to about 40 minutes, to which was added another 40 minutes or so of combustion and post-combustion in the ash compartment.

On the grate of the hearth, with natural draught (10 mm water column of pressure difference), 30 kilograms of coke per hour burned under normal circumstances; the fact that this was also the average consumption per corpse during the period of heaviest use of the furnace (and it was not by [40 min ÷ 60 min/h × 30 kg/h =] 20 kg in 40 minutes) is explained by the fact that the furnace operated with a forced-draft device with a maximum pressure difference of 30 mm water column. In the Gusen furnace, this corresponded to the burning of 45 kg/h of coke. Hence, within 40 minutes, the consumption was precisely (40 min ÷ 60 min/h × 45 kg/h =) 30 kg.

According to Topf Invoice No. 41 D 2249 dated Jan. 27, 1943, the three forced-draft devices at Crematorium II had a capacity of 40,000 m³/h at a pressure difference of 30 mm water column,[59] but they were damaged beyond repair a few days before March 24, 1943, “after the first full use,” so they were disassembled and taken back by the Topf Company. As a result of this serious failure, the Auschwitz Central Construction Office decided not to install the forced-draft devices in Crematorium III, as had originally been planned.[60]

II. Open-Air Burning[61] on Pyres in the Camps Bełżec, Treblinka and Sobibór

1) Cremation Experiments by Australian Researchers

In a book that appeared in 2013,[62] I have dealt in some detail with the issue of the alleged mass cremations of corpses on pyres in the camps of Bełżec, Treblinka and Sobibór.

In a more recent work,[63] I have reiterated this issue, supplementing the data on the clearing of forest areas for the mass cremation of the corpses of the alleged gassing victims with important documents, and adding fundamental meteorological data.

The study “Experimental Study on the Fuel Requirements for the Thermal Degradation of Bodies by Means of Open-Pyre Cremation”[64] appeared in 2018, but remained unnoticed among revisionists until its publication on the CODOH website.[65] This study offers additional relevant data on the issue of wood requirements for an outdoor cremation.

Germar Rudolf has provided a concise summary of this, accompanied by appropriate considerations,[66] outlining its general context as follows:

“A team of researchers from the School of Civil Engineering at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, led by Luis Yermàn conducted a ‘series of experiments, using pig carcasses as surrogates for human bodies,’ in order ‘to establish the conditions that will result in total destruction of organic matter in the cremation of bodies by means of an open pyre,’ with a main focus on the amount of dry pine wood needed for an almost complete destruction of the carcasses investigated. They published the results of their experiments in 2018 (Yermán et al.). Due to its importance, the Bradley Smith Charitable Trust, aka CODOH, obtained a license to republish the entire article in Inconvenient History, where it is featured in the same issue as this present article”.

The purpose of the experiments was related to a crime case and aimed at

“establishing the validity of a forensic hypothesis [that] relates to what has been referred to as the ‘Historical Truth’ in the case of the 43 disappeared students in Ayotzinapa, Mexico. A forensic investigation concluded that multiple bodies (up to 43 bodies) were cremated in the municipal dump of Cocula. The human remains discovered in the dump showed no remnants of DNA due to the high level of heat exposure. A subsequent expert panel concluded that there was a need to conduct realistic experiments to establish the detailed characteristics of the fire necessary to achieve the observed levels of cremation (i.e. intensity of the fire, amount of combustible materials necessary, etc.)” (p. 63)

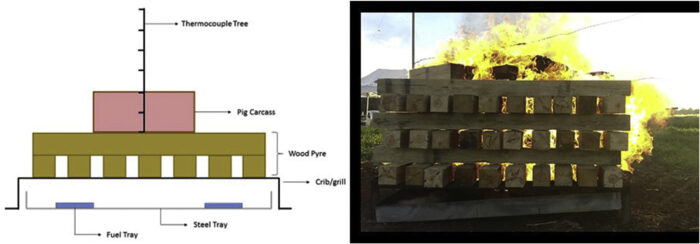

Before presenting the results of the experiments, it is important to describe their essential elements.

1) Pyre Structure:

“The wood pyre was placed over a metallic support that consisted of three parts: (i) a metal frame constructed from 50mm L-section steel, (ii) a metal grate that sits inside the frame to prevent wood falling below whilst also providing adequate air entrainment, (iii) a metallic tray below the frame to collect ash and any dripping fats. The wood pyres were built using 10 cm square section logs that were 1.5m long. The logs were placed in cross hatched manner, 10 per layer, with a 2 cm gap between each log to allow adequate airflow.” (p. 65; see Document 17)

2) Wood

Pine-tree logs of the above dimensions, which were chosen for a specific technical reason:

“The length-to-thickness ratio of the wood logs was kept constant throughout the tests with a value equal to 15. The length-to-thickness ratio was chosen to ensure self-sustaining fires and maximum burning rates, thus best possible burning conditions. In this way, pyres were rectangular-shaped of 1.50 x 1.18m. The height of the pyres varied according to the amount of wood used.” (p. 65)

The wood had a moisture content between 14% and 19%, and a higher heating value (HHV) of 17.7 kJ/g, or 4,230 kcal/kg (pp. 66f.).

3) Cremated Objects

Pig carcasses between 53 and 81 kg:

“Pig carcasses have been commonly used as surrogates for human bodies, and while differences between organic matter from a pig and a human body are significant, the similarities have been long recognized.” (p. 64)

“The pigs were euthanized humanely approximately five hours before the experiments. Each pig carcass was wrapped in a woollen blanket of 1.8 kg and placed in the centre of the pyre. The blankets simulate clothing and also act as a wick absorbing fat that is being released from the burning carcass. When two carcasses were used, these carcasses were placed with 10 cm separation, and ensuring stability of the pyre throughout the fire. When four carcasses were used, the same configuration was used, but placing the carcasses in two layers of two pigs each.” (p. 66)

4) Lighting of Pyres:

“The fires were initiated with a mixture of kerosene/n-heptane placed in 4 containers (commercial baking trays 200 300 mm) placed inside the metallic tray. To sustain the initial fire in the containers for at least 5 min, each tray contained 600 mL of kerosene and 100 mL of n-heptane. The point at which all containers were ignited was considered as the start of the fire.” (p. 66)

5) Method:

Six experiments were carried out, varying the number of carcasses burned on the pyre, and the ratio of wood mass to carcass mass, as shown in the following table (p. 65):

Mass RatioAnimal Mass [kg]Fuel Mass [kg]

| Experiment | # of Animals | Fuel/Animal</th | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 77 | 154 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 53 | 159 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 81 | 405 | 4 | 1 | 9 | 56 | 504 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 176 | 880 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 209 | 1045 |

6) Results:

“It is important to note that, with four carcasses, the [temperature] decay is much faster than with two. Within less than 800 s, temperatures start to decay, only increasing once the new fuel is added. This indicates that an increase in the number of animals does not have a positive effect on the crib, even under improved burning conditions. Burning for this test is characterized by small flames and therefore low temperatures. […]

It can therefore be concluded that increasing the number of animals does not have a positive effect on the crib at this F/A = 5 ratio, even if the animals are smaller.

This is an important conclusion because it suggests that, for this F/A ratio, to establish the minimum amount of fuel required for incineration of multiple animal carcasses, it is not necessary to conduct experiments with more animals. The minimum amount of fuel required will be that necessary for a single animal because the carcass to carcass interactions are detrimental to the fire.” (pp. 69-70)

7) Conclusions:

“1. As the net heat supply to the animal surface decreases, combustion supported by the degradation of animal carcasses ceases because of flame quenching associated with the reduced generation of combustible gases

- A minimum of nine times the weight of the body in dry wood is necessary to achieve almost complete destruction of all organic matter (<10%) when the pyre is left unattended

- Under ideal conditions (smaller carcasses and continuous feeding of fuel) a minimum of 5 times the weight of the body in dry wood is necessary to achieve almost complete destruction of all organic matter (<10%)

- For all conditions studied, the presence of a carcass will always result in weakening of the fire but will not affect the structure of the flames significantly. Only if the amount of fuel is very small (F/A = 2) then the heat sink associated to the carcass will reduce the fire size to a point where flame extinction occurs

- Carcass to carcass interactions with the pyre result in a stronger endothermic impact of the carcass on the crib, thus it is less efficient to cremate multiple carcasses than a single carcass

- Self-sustained burning of animal carcasses in an open pyre configuration is not possible. Significant energy from the wood is always necessary to avoid quenching.

All estimates provided in the above conclusions are conservative given that, in all cases studied, significant organic matter was still left in all the animals cremated.” (pp. 72f.)

2) Comparison of the Australian Experiments’ Results with Orthodox and Revisionist Conclusions

My most in-depth study of the incineration of human corpses on pyres is contained in Chapter 12 – titled “Cremating the Alleged Victims in the ‘Aktion Reinhardt’ Camps” – of the above-mentioned book The “Extermination Camps” of “Aktion Reinhardt”. The work is a meticulous and radical refutation of the theses expounded by Jonathan Harrison, Roberto Muehlenkamp, Jason Myers, Sergey Romanov and Nicholas Terry in a PDF file they posted online in 2011 under the title Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka. Holocaust Denial and Operation Reinhard: A Critique of the Falsehoods of Mattogno, Graf and Kues” In the aforementioned chapter, I dealt specifically with Roberto Muehlenkamp’s thermotechnical ramblings. In Chapter 8 (“Burning of the Corpses”), paragraph “Fuel Requirements,” he assumed a fuel-to-organic-substance ratio of 0.56 : 1, meaning that 0.56 kg of wood is said to have been enough to burn 1 kg of corpse![67] Based on this absurdity,[68] he calculated the wood requirements for incinerating the alleged victims of the Reinhardt Camps: 27,874,560 kg.[69] This was his response to the points I had made in the book coauthored by Jürgen Graf, Thomas Kues and myself, titled Sobibór: Holocaust Propaganda and Reality.[70] In the book’s paragraph 5.3.3. titled “Fuel Requirements for the Cremation of One Body” (pp. 133-136) I adduced experimental results of various cremation/incineration systems:

- Teri cremation furnace: 1.82 kg of wood for each kg of body

- Mokshda system: 2.14 kg/kg

- Fuel-efficient Crematorium: 3.6 kg/kg

- Traditional Hindu pyre: 7.14 kg/kg

- Air Curtain System (technical expert report): 3.04 kg/kg

- Burning of carcasses: 3.6 kg/kg (based on the total weight of the ashes)

- Burning of poultry carcasses in Virginia: 4.4 kg/kg

- Combustion experiments by Mattogno: 3.5 kg/kg.[71]

Of these eight systems, the one most closely resembling the incinerations attributed to the Reinhardt camps is evidently No. 4, the traditional Hindu pyre system (7.14 kg), but in order to avoid disputes and objections, I adopted the lower value of 3.5 kg in the Sobibór study.

The Australian experiments discussed here have shown that, for an almost total destruction of carcasses, an amount of wood with a ratio of 5 : 1 is required, but this applies only to the burning of a single carcass.

Since the burning in the Reinhardt camps was presumably done on huge pyres with thousands of corpses arranged in six to twelve layers (see below) and the end result was almost complete incineration (“Unburnt bones that were difficult to crush were thrown into the fire a second time”[72]), a required amount of 9 kg of wood per 1 kg of organic matter would have to be assumed, as I shall make clearer below. However, in order to demonstrate a fortiori the material impossibility of the mass-incineration operation, I shall consider the ratio of merely 5 : 1 for my subsequent calculations.

This value is 1.4 times higher than the one I have proposed, but a full 8.9 times higher than Muehlenkamp’s value of 0.56, which is already visually refuted and ridiculed by two photographs showing a merely charred carcass after a cremation attempt using a wood-to-carcass ratio of 2 : 1, hence almost four times higher than Muehlenkamp’s value (see Document 18)

While this is devastating for Muehlenkamp’s thesis (the requirement of wood for the incineration of the alleged victims of the Reinhardt camps thus rises from 27,874,560 to 248,083,584 kg!), the revisionist thesis is not only unaffected by this, it is in fact bolstered. Indeed, it should be emphasized that the question of wood consumption (and cutting) is the essential criterion for judging the reliability of the story – and thus the practical feasibility of the immense mass gassings with subsequent incinerations in the Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka camps.

In the book The “Extermination Camps” of “Aktion Reinhardt,” I have accepted, for the sake of the argument, Muehlenkamp’s (purely conjectural) data on the average weight and composition of corpses for each individual camp, and made the necessary calculations based on them, which I summarized as follows:

| Camp | # of Corpses | Average Mass of Exhumed Corpse [kg] | Required Dry/Green Wood for Cremation of Exhumed Body [kg] | Total Dry Wood Required [t] | Total Green Wood Required [t] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bełżec | 441,000 | 23.65 | 132 / 250.8 | 58,212 | 110,602.8 |

| Sobibór | 300,000 | 36.43 | 133 / 252.7 | 39,900 | 75,810.0 |

| Treblinka | 781,000 | 18.95 | 134 / 254.6 | 104,654 | 198,842.6 |

| Totals: | 1,522,000 | 202,766 | 385,255.4 |

The assumption was that the wood-to-corpse ratio for a normal corpse was 2.82 : 1 (resulting from a paper issued by the British Environment Agency concerning the cremation of 300 cow carcasses).[73] Since the minimum experimental ratio (for a single carcass) is 5 : 1, all values given in the table must be multiplied by (5 ÷ 2.82 =) 1.77, resulting in the following changes:[74]

| Camp | # of Corpses | Average Mass of Exhumed Corpse [kg] | Required Dry/Green Wood for Cremation of Exhumed Body [kg] | Total Dry Wood Required [t] | Total Green Wood Required [t] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bełżec | 441,000 | 23.65 | 233 / 440 | 102,753 | 194,040 |

| Sobibór | 300,000 | 36.43 | 235 / 447 | 70,500 | 134,100 |

| Treblinka | 781,000 | 18.95 | 237/ 450 | 185,097 | 351,450 |

| Totals: | 1,522,000 | 358,350 | 679,590 |

The wood/corpse ratios are never equal to 5 : 1 (the highest, the one for Sobibór, is 6.54 : 1) because these are corpses that were first interred and then exhumed. Therefore, the longer they had been interred, the more of their original calorific value they had lost due to decomposition (loss of fat and protein), according to the corpse compositions hypothesized by Muehlenkamp. This is precisely why I warned:[75]

“[…] it is important to underline that these consumptions refer to the types of corpses imagined by Muehlenkamp and, that they can vary considerably if different starting conditions regarding their composition are assumed. But because this is, in fact, a reply to Muehlenkamp, who, with great modesty, considers himself as a worldwide exterminationist cremation specialist for the camps of the ‘Aktion Reinhardt,’ the listed results have a historiographic value, and if only by invalidating Muehlenkamp’s results.”

However, it is certain and important to reiterate that the coefficient 5 of the Australian experiments refers to carcasses of “freshly euthanized pigs.” This does not apply to bodies that were interred and then exhumed. Not to mention that the Jews deported to the Reinhardt camps did not have normal weights at all. Muehlenkamp himself states that the Polish Jews were on average 1.60 meters tall, which corresponds to a normal weight of 55.66 kilograms, but he considers them on average slimmed down by more than 12 kilograms, assuming an average weight of just 43 kilograms.[76] From this he then derived (again conjecturally) the weights of the exhumed corpses that I reported in the tables shown earlier.

The Australian experiments have shown that “it is less efficient to cremate multiple carcasses than a single carcass.” The cremation experiment of two pairs of overlapping carcasses showed that “an increase in the number of animals does not have a positive effect on the crib, even under improved burning conditions.”[77]

However, the situation of the pyres in the Reinhardt camps described by witnesses was nothing short of catastrophic. Muehlenkamp made a description of a typical Treblinka pyre on the basis of (contradictory) testimonies. Based on this, he made three hypotheses regarding the layering of corpses on it (with two different sizes of bodies):[78]

- “about 6 layers of about 583 bodies each” (cremation grate of some 90 m2)

- “about 8 layers of about 438 bodies each” (cremation grate of some 66 m2)

- “about 12 layers of about 292 bodies each” (cremation grate of some 90 m2)

- “about 16 layers of about 219 bodies each” (cremation grate of some 66 m2)

In all these cases the total load on a cremation grate was 3,500 corpses! Thus, it can be safely said that, even in the best-case scenario, it would have been impossible to burn a layer of six corpses even with the empirically derived ratio of 9 : 1, the result of which was still a “significant visible organic residue.”[79]

If incineration of such loads of corpses on such a grate were possible, they would have required incalculable amounts of wood, all the more so since the results, if we follow the orthodox narrative, had to be bones that were burnt to such a degree that they were brittle and thus could be smashed with mallets.[80]

The type of wood allegedly used creates additional insurmountable problems. It would in fact have been fresh wood, the ignition of which would have required huge quantities of liquid fuels. The wood moreover would have consisted mainly of logs and large branches, which are even more difficult to ignite. This is abysmally worse than the 1.5-m-long dried logs with a 10 cm square cross section used in the Australian experiments.

Another certain result of these experiments is that “self-sustained burning of animal carcasses in an open pyre configuration is not possible,” which disproves the related testimonial rantings and rules out the possibility of the use of less wood for burning corpses.

In my book The “Operation Reinhardt” Camps Treblinka, Sobibór, Bełżec, I quoted from orthodox sources the times available for cremating the corpses in each camp, and the number of inmates assigned to cutting wood in the surrounding forests (the so-called Waldkommandos – forest units),[81] while always using the upper values given in those sources:

- Bełżec: 105 days and 60 inmates

- Sobibór: 365 days and 40 inmates

- Treblinka: 122 days 100 inmates.[82]

From the “Headquarters’ Special Order” (Kommandantursonderbefehl) of the “Wehrmacht-Ortskommandantur [local headquarters in] Riga” dated June 16, 1944 with the subject “Heating material supplies 1944/45,” it appears that the daily productivity in logging of a prisoner of war was 0.63 tons.[83] This empirical data can also be considered valid for the “forest units.” Based on it, the wood requirements for each camp can be calculated as follows:

| Camp | # of Corpses | Days Available | Loggers Available | Daily yield [t] | Total yield [t] | Total Need of Green Wood [t] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bełżec | 441,000 | 105 | 60 | 0.63 | 3,969 | 194,040 |

| Sobibór | 300,000 | 365 | 40 | 0.63 | 9,198 | 134,100 |

| Treblinka | 781,000 | 122 | 100 | 0.63 | 7,686 | 351,450 |

| Totals: | 1,522,000 | 20,853 | 679,590 |

Within the available time, the inmates of the forest unit would have been able to cut just (20,853 ÷ 679,590 =) 3.06% of the amount of wood needed for the claimed operation. Since their daily productivity for the three aforementioned camps was (days × loggers × 0.63 t/day =) 37.8, 25.2 and 63 tons, respectively, they would have needed for Bełżec (194,040 t ÷ 37.8 t/day =) 5,133 days, for Sobibór (134,100 t ÷ 25.2 t/day =) 5,321 days and for Treblinka (351,450 t ÷ 63 t/day =) 5,578 days to complete the work. In the best-case scenario (Bełżec), cutting wood and burning corpses would have taken 14 years![84]

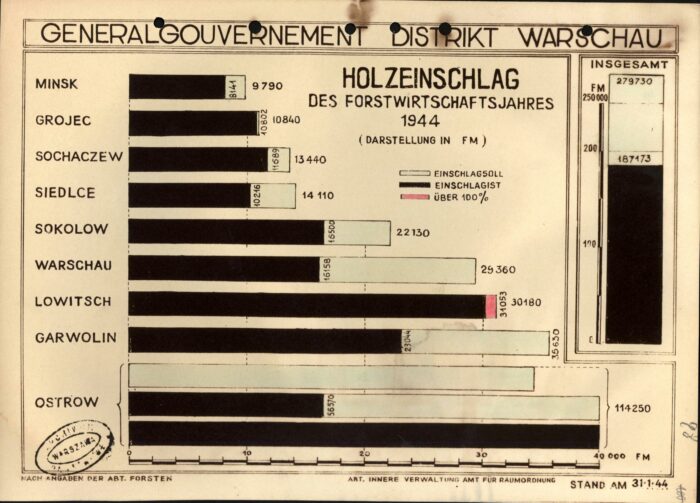

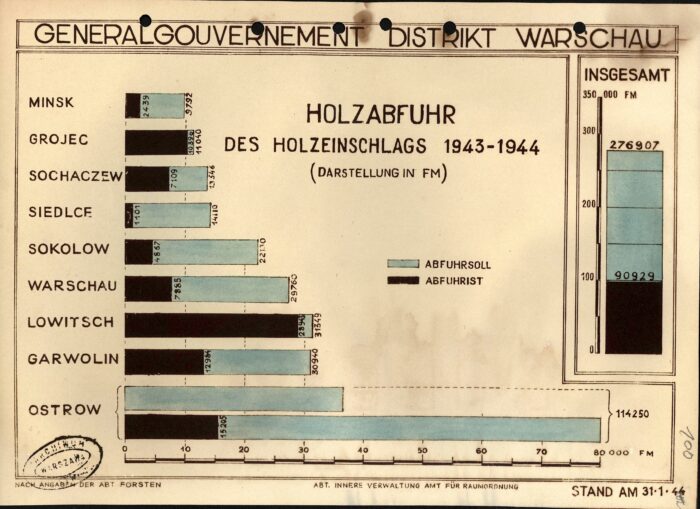

The wood requirement for Treblinka over four months (April to July 1943) is also resoundingly refuted by German documentation of wood cutting in the Warsaw district. For greater clarity, I reiterate here what I wrote in the book The “Operation Reinhardt” Camps:[85]

“In the General Government, the management of forests depended on the ‘Main Department Forestry’ of the local government. In the Warsaw District, it was represented by the Forestry Department headed by District Forester Küchler. Each of the 10 counties (Kreishauptmannschaften) of this district, with the exception of the capital Warsaw, had a main forestry (Oberförsterei) that was dependent on the above-mentioned office, which was in charge of wood supply. The wood was first cut (Holzeinschlag, wood cutting) and then transported little by little to the recipients (Holzabfuhr). Each county was assigned a certain amount of wood to be cut, which in some cases was even slightly exceeded. These activities were documented in detail. Some documents have been preserved and show exactly how much wood was cut and transported at various dates. A chart on ‘Wood Cutting for the Economic Forestry Year 1944’ (‘Holzeinschlag des Forstwirtschaftsjahres 1944‘) shows the situation as of January 31, 1944 for the Warsaw District [see Document 19]. The amount of wood to be cut (Einschlagsoll) was 279,730 solid cubic meters ([Festmeter] fm); the amount actually cut (Einschlagist) was 187,173 fm. The graph regarding ‘Wood transport of the wood cut 1943-1944’ (‘Holzabfuhr des Holzeinschlages 1943-1944‘), with reference to the same date, gives the amount of wood that had been taken away: it amounted to 90,929 fm [see Document 20]. It is worth mentioning that, according to Arad, in Treblinka ‘the entire cremation operation lasted about four months, from April to the end of July 1943’ (Arad 1987, p. 177)”

Now, at the Warsaw District, the wood cutting of 1943 until 31 January 1944 had produced 187,173 fm (=m³), or about 168,500 tons, of which 90,929 m³, or about 81,800 tons, had been taken away.

Treblinka Camp was located in Sokołow County, bordering on Ostrów County, to which nearby Małkinia belonged. The charts show that the actual wood production of these two counties had been 16,500 and 56,570 m³, respectively, or about 14,850 and 50,900 metric tons, of which 4,867 and 15,205 m³, or about 4,400 and 13,700 metric tons, had been delivered as of January 31, 1944.

All in all, the amount of wood hauled away from the two counties was about (4,400 + 13,700 =) 18,100 metric tons. This was the wood cut in 1943 and January 1944, available and therefore usable as of January 31, 1944.

As of March 1, 1943, the territory of the Warsaw District had an area of 17,168 km2, and a population of about 2,699,000 people. In it, Sokołow County had an area of 2,565 km2 and about 172,000 inhabitants, and Ostrów County 1,366 km2 and about 109,000 inhabitants.

The new conclusion is that the inmates of the forest unit in Treblinka were supposed to cut 351,450 tons of wood (or 632,610 tons with a ratio of 9 : 1) within four months of 1943, while in the whole of 1943, including January 1944, only 168,500 tons were cut in the entire Warsaw district, hence less than half of what this camp alone would have needed! This amount, moreover, included construction timber, so that the share of firewood was even lower.

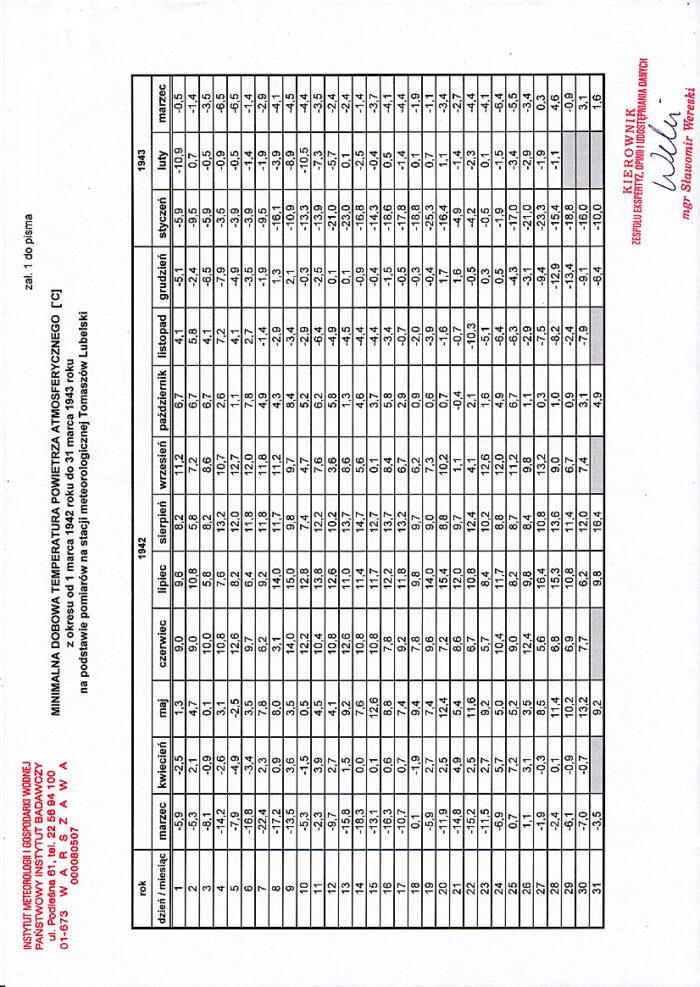

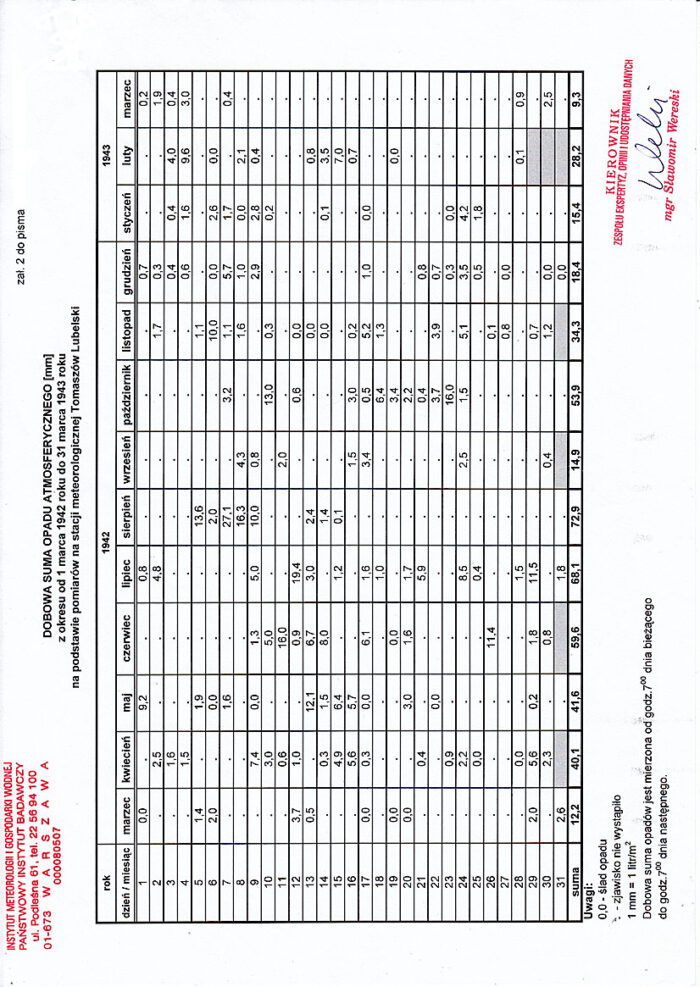

An additional problem made the Reinhardt camps’ claimed cremation procedure even more absurd: that of weather conditions. In the above-mentioned book, I published daily weather data from the station at Tomaszów Lubelski (8 km from Bełżec) from December 1942 to March 1943, and at Ostrów Mazowiecka (about 20 km NNE of Treblinka) from April to July 1943, the respective periods of the alleged mass incinerations.[86]

From mid-December 1942 to March 1943, there were 31 days of snowfall in the Bełżec area, which dropped about 60 cm of snow and rain. The camp and forests were covered with snow. For 102 days, temperatures were below the freezing point (0°C); for 21 days, temperatures fell below -10°C (14°F), for 5 days they ranged from ‑21°C to ‑25.3°C (-6°F to -14°F; see Documents 21 and 22).

From April to July 1943, there were 49 days of more or less heavy rain in the Treblinka area, totaling 280.1 mm of rain (11 in), or 280 liters of rain per square meter of cremation grate. Under such conditions, the burning of (441,000 ÷ 105=) 4,200 corpses per day in Bełżec and (781,000 ÷ 122 =) 6,400 in Treblinka is simply a blatant absurdity.

Since the mass incineration of 1,522,000 corpses in the camps of Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka was materially impossible, it follows that the killing of 1,522,000 Jews was also impossible. This definitively and incontrovertibly demolishes the fantastic tales of the Aktion Reinhardt “extermination camps.”

In my book The Einsatzgruppen in the Occupied Eastern Territories: Genesis, Missions and Actions, Part Two: Aktion 1005,[87] I have demonstrated that the claimed immense incineration of Jews presumably shot by the Einsatzgruppen at multiple sites in the German-occupied eastern territories is absurd, even if assuming merely a wood-to-body ratio of 3.5 (average 132 kg of wood per corpse). Since these burnings are said to have occurred on pyres where bodies allegedly had been stacked in many layers, as in the camps at Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka, everything I have noted above applies inescapably also to these claimed scenarios. Matters turn out to be even more grotesquely unrealistic when assuming a more likely wood-to-corpse ratio of the 5 : 1 or even 9 : 1. In these cases, even more unimaginable quantities of wood would have been required, and extremely long procurement times would have resulted, making the relevant operations even more nonsensical.

I leave the imbeciles among the adherents of the orthodox narrative with the meager consolation that all this “was technically possible because it happened.”